Maine Home Garden News — July 2019

- July Is the Month to . . .

- Crop Rotation for Home Gardeners

- Managing Invasive Plants in Maine

- Japanese Stewartia: An Ornamental Tree for Every Season

- Volunteer Spotlight: Growing with Children at Camp Discovery on Webb Pond

- Food & Nutrition: The Missing Ingredient: Adherence of Food Blog Salsa Recipes to Home Canning Guidelines

July Is the Month to . . .

By Caragh Fitzgerald, Associate Extension Professor, UMaine Extension Kennebec County

- Learn those weed pests! Look those stubborn weeds up on the Native Plant Trust’s GoBotany site, NRCS’ Plants interactive key, or University of Missouri’s Weed ID Guide. A great paper reference is Weeds of the Northeast by Uva, Neal, and DiTomaso. Still stumped? You can always send a picture or bring a sample to your county Cooperative Extension office.

- Fertilize and remove spent blooms on your annual flowers for a continuous show.

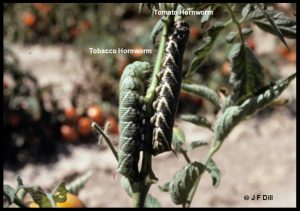

Watch for hornworms on your tomatoes. You might also find them on peppers or eggplant! Hand-picking them daily works well for small plantings. They are well-camouflaged. Sometimes you can find them by spotting their droppings or by going out at night with a blacklight flashlight.

Watch for hornworms on your tomatoes. You might also find them on peppers or eggplant! Hand-picking them daily works well for small plantings. They are well-camouflaged. Sometimes you can find them by spotting their droppings or by going out at night with a blacklight flashlight.

- Pick beans, peas, and zucchini every two days to keep them from getting overly large.

- Keep planting. Fill that spare garden space with beets, beans, kale, lettuce, carrots, and bunching onions.

- Donate extra produce to your local food pantry. Call ahead first to be sure they can handle it (some don’t have cold storage) and find out when you can drop it off.

- Visit your local farmers’ market to fill in the gaps of what you’re not growing yourself.

- Battle Japanese beetles by hand-picking early in the morning into a container of soapy water. If you use a trap, remember that it can attract more beetles to the area, so locate it away from the plants you’re trying to protect. Take solace in knowing that populations can vary from year to year. A big population one year does not necessarily mean you’ll have a lot the following year. Here’s a great video outlining management strategies.

- Set your mower at its highest level and do not remove lawn clippings. This will help keep turf healthy in the summer heat. Learn more about other best practices for a healthy, low-input lawn.

- Protect yourself from ticks and check yourself after being outside. The UMaine Tick Lab can identify ticks. If you remove one that’s embedded, they can test it for tick-borne diseases for a fee.

Crop Rotation for Home Gardeners

By Pamela Hargest, Horticulture Professional, UMaine Extension Cumberland County

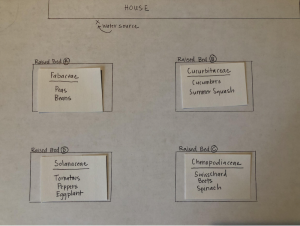

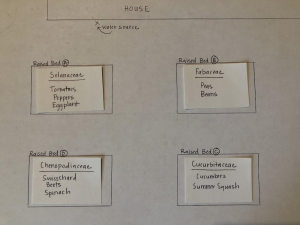

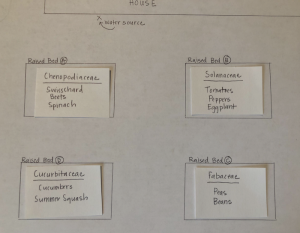

No matter how small your garden is, it’s always beneficial to rotate your vegetables. Crop rotation is essential for producing quality vegetables, deterring pests and diseases, and maintaining good soil fertility from year to year. An important first step with planning crop rotation is to create a plan either in the fall or winter months before the growing season begins. This plan should lay out where your crops will be planted in your garden for the next 3 or more years and can be as detailed as your time and budget allows.

Start with a simple base map of your garden; be sure to label where you have any perennial herbs and/or vegetables that will be overwintering (e.g. Garlic, Thyme, Sage). After your base map is complete, list all of the vegetables you usually grow in your garden or the ones you hope to grow if this is your first year. Then, group those vegetables by their corresponding plant families (include any overwintering vegetables). For a list of plant families, check out Plant Rotation in the Garden Based on Plant Families by Elsa Sanchez, professor of horticultural systems management and Kathy Demcheck, senior extension associate in plant science from Penn State Extension. Plants belonging to the same family are usually susceptible to the same pests and diseases and require similar nutrients, which is why basic crop rotations are usually based on plant families.

Once you have your vegetables in their appropriate group, label small index cards for each of the plant families and crops in those families. Use these cards with your garden map, in addition to laying them out in order of time, to visualize how you might rotate these vegetables throughout your garden and into the future1. Keep in mind that you’ll want to avoid planting crops from the same family in the same place for another 3 years or until the rotation starts again. With a small garden space, it can sometimes be beneficial to avoid planting an entire family for a year or two, especially if you are finding a particular pest or disease to be an on-going nuisance. This practice can dramatically reduce pest populations or the possibility of a disease by removing the host plant and as a result, disrupt the disease or pest’s life cycle.

Another important factor in planning your crop rotation is your crops’ nutrient requirements. Rotation will ensure you are optimizing your soil’s fertility while also cutting down on your inputs (e.g. fertilizers). On each card, note whether your vegetables are light, medium, or heavy feeders. If a vegetable produces a fruit and/or has a long growing season (e.g. tomatoes, potatoes, corn), then it is likely a heavy feeder and will require more nutrients. If a vegetable is harvested for its greens or roots (e.g. radish, lettuce, carrots) and/or has a short growing season, then it is likely a light or medium feeder and will require less nutrients. In addition to rotating families, try alternating between heavy and light/medium feeders in each area of your vegetable garden.

Crop rotations in vegetable gardens often extend beyond rotating just vegetables and will frequently use cover crops or “green manures” every other year or so to serve many functions: preventing erosion, adding organic matter, improving drainage, suppressing weeds, holding nutrients, as well as fixing nitrogen in your garden beds. Cover crops are incredibly low maintenance and very easy to grow. For example, in late August or early September, after growing and removing cucumbers, sow that area to peas and oats; the tender peas and oats will “winter kill” after a hard frost and will not need to be removed, also making a great natural mulch in the Spring. Late October sown Rye however, a more challenging example, will not winter kill and will need to be worked into the soil before it develops seeds or else risk it becoming a weed problem in your next crop.

Home gardeners can purchase small quantities of cover crop seeds from Maine-based seed companies, such as Johnny’s Selected Seeds and Fedco Seeds. For more information about cover crops, check out Cover Crops for Home Gardeners (PDF) by Lois Berg Stack.

Crop rotation can be as simple or complex as you want to make it, don’t get discouraged trying to incorporate everything or thinking you can’t grow something for years. It’s okay to compromise and not follow the “rules” every single year, especially if you haven’t observed a pest, disease or fertility issue in that area. Stick to the basics: divide up your garden, alternate plant families, break repetitive cycles, and build long-term fertility and soil structure with cover crops.

- Year 1

- Year 2

- Year 3

Managing Invasive Plants in Maine

By Matt Wallhead, Ornamental Horticulture Specialist/Assistant Professor, UMaine Extension, Orono

Approximately a third of Maine’s vegetation is comprised of species not native to the state. Invasive plants are those that are non-native and have the potential to cause environmental and/or economic damage. Invasive plants can be introduced to an area in a variety of ways. Many invasive species were first brought to the state for ornamental purposes, including Norway maple, burning bush, and Japanese barberry. Accidental introductions and wildlife assisted dispersal are common as well. For instance, it’s not very difficult to find glossy buckthorn growing under power lines where birds perch.

The most effective way to manage invasive species is to prevent their introduction. Once invasive plants have become established in an area they can become incredibly challenging to eradicate. For example, it may take 10-12 years to effectively manage an established stand of Japanese knotweed. Maine recently adopted rules that prohibit the sale of 33 terrestrials plant species. Make sure to check the list of banned plants before bringing any plant material purchased out of state into Maine. Better yet, purchase all of your plant material from a local garden center, greenhouse or nursery. If you need help finding somewhere local to purchase your plants, check out Bulletin #2502, Native Plants: A Maine Source List or contact your UMaine Extension county office for suggestions or the Plant Sources list managed by the state.

With enough determination and persistence, successful management of existing stands of many invasives can be achieved without the use of herbicides. Hand-weeding, tarping (i.e. covering with a heavy material such as a thick tarp, heavy plastic, or old carpet), frequent (weekly) mowing, and digging can all be effective strategies. Keep in mind that digging can potentially cause a larger problem when roots of spreading invasives are broken apart and pieces (new propagules) are left behind or, even worse, transported to a new site when soil from the excavated area is piled elsewhere. Implementing more than one of these approaches over the long haul is often what puts gardeners on the winning side of this war (it’s not a single battle).

One success story:

A garden overrun by bishop’s goutweed (Aegopodium podagraria) was recovered after initially doing a thorough digging in the spring to remove as much of the roots as possible by hand. Perennial plants that we wanted to keep, but were growing among the goutweed were dug, thoroughly weeded (almost to the point where they were bare root), and potted up to be monitored for any stray goutweed that may still have been lurking in their root system. Then, the area was covered with a heavy tarp. This may be too aesthetically shocking for some, so bark mulch or straw can be used to soften the look. We avoided planting anything in the area until early fall. When we lifted the tarp, we did a final weeding of the goutweed that was miraculously still growing under there. Replanted perennials were mulched using a thick layer of newspaper (4-5 sheets) topped with bark mulch to suppress any remaining goutweed, but the job still wasn’t done. We were vigilant about monitoring on a weekly basis the following season, pulling ANY small piece of goutweed that popped up as soon as it was noticed. Even after a few years, a few strays still pop up here and there, but we’ve considered ourselves the victor.

The key to success is to commit (for the long term) to not allowing the plants to photosynthesize. This can take years and, even when a stand seems to be gone, it’s important to continue monitoring.

Some jobs will require the use of herbicides or professional help. The state maintains a list that includes companies that are licensed to provide services for control of invasive terrestrial plants in Maine. The list is not a complete list of licensed companies and any service providers wanting to be listed should contact the Board by emailing pesticides@maine.gov or calling 207.287.2731.

To help citizens learn to properly identify invasive species, the Maine Natural Areas Program just released a very informative and useful guide titled Maine Invasive Plants Field Guide (PDF). The field guide covers 46 species of invasive plants and is waterproof, portable, and ring-bound so that it can be expanded easily. Additional help identifying invasive plants is available through the UMaine Cooperative Extension Ornamental Horticulture program.

Individuals interested in participating in a citizen scientist project could consider investigating iMapInvasives. iMapInvasives is an online, GIS-based, data management system used to assist scientists and natural resource professionals in mapping the presence and location of invasive plants in Maine. So, no matter what your interest level, there are lots of resources for learning more about invasive plants and how to manage them available for Maine’s residents. Contact Dr. Matt Wallhead at matthew.wallhead@maine.edu or Nancy Olmstead at nancy.olmstead@maine.gov for more information or with specific questions.

Japanese Stewartia: An Ornamental Tree for Every Season

By Leala Machesney, Horticulture Student, University of Arkansas

Some trees provide ornamental interest for only a few weeks, but the Japanese stewartia (Stewartia pseudocamellia) remains decorative year-round. This stewartia is prized for two features: its elegant white flowers and multi-colored, exfoliating bark. The flowers, which resemble camellias, are 2 to 3 inches in diameter and begin to open in late June or early July. Although these flowers won’t bloom all at once, the tree will continue to flower for several weeks. Once the attractive display of flowers is over, the bark of Japanese stewartia can still be admired. The mottled bark comes in shades of gray, orange, tan, olive, and burnt umber. In a snowy winter landscape, the bark on a group of Japanese stewartia is picturesque. While Japanese stewartia is considered ornamental chiefly for its flowers and bark, the fall color of this tree can also be magnificent. It is most commonly a purple or bronze, but can occasionally be orange or red. Orange or red coloration is more typical of trees growing in full sun, or of cultivars that reliably possess this kind of fall color.

As its common name suggests, Japanese stewartia is native to woodlands of Japan, but can also be found in Korea. The soils in these woodlands, like many of the soils in Maine, tend to be slightly acidic. A hardiness rating from zones 5 to 7 ensure it will overwinter reliably in many parts of Maine. Some have even reported success growing this tree in zone 4. While you’ll see more flowers and dependably vibrant fall color from a stewartia situated in full sun, it will tolerate partial shade. At full maturity, the Japanese stewartia will have a rounded habit and reach heights of 20 to 40 feet. This rounded habit comes with age; young trees will be pyramidal and slowly develop a more rounded shape. If you’re considering planting a Japanese stewartia, be aware that the species is often slow-growing, but a mature Japanese stewartia is worth the wait. Its slow growth can also be a benefit to gardeners looking for low maintenance trees, as pruning is rarely necessary. On top of an infrequent need for pruning, Japanese stewartia also lacks any major pest and disease problems, so pesticide applications may never be needed. Trees do require soils that are high in organic matter. If your soil isn’t sufficiently high in organic matter, consider amending with compost prior to planting.

There are several cultivars of Japanese stewartia that merit special attention. S. pseudocamellia ‘Ballet’ has long, graceful sweeping limbs and glossier leaves than the species. It also has larger flowers than you’d typically find in the species. The inside of S. pseudocamellia ‘Mint Frills’ petals are tinged with pale green, and make a nice complement to the creamy white. However, this difference in coloration isn’t a drastic departure from the ordinary white coloration of Japanese stewartia flowers. If you can’t provide a Japanese stewartia with full sun, consider the cultivar ‘Harold Hillier,’ which boasts reliable orange fall color without full sun. S. pseudocamellia ‘Cascade’ has a semi-weeping form that can look very dramatic, but this cultivar grows even more slowly than the species. ‘Milk and Honey’ provides larger blooms than the species, and more of them. Its bark color is also a brighter intensity. Unlike the species, which has a cup-shaped flower, the flowers of ‘Milk and Honey’ are flat, and its fall color tends to be orange-red rather than the purple more typical of Japanese stewartias. Finally, some nurseries may offer the rare S. pseudocamellia ‘Pink Form.’ Flowers on this tree are tinged pink. Like ‘Mint Frills,’ the color difference in ‘Pink Form’ is not a great deviation from the species. Blooms appear to have a pink blush, rather than being truly pink. Regardless of what Japanese stewartia you may be considering, any one is sure to serve as an arresting addition to a garden.

Further Reading

Dirr, M. (1983). Manual of woody landscape plants: their identification, ornamental characteristics, culture, propagation and uses. Champaign, Ill, Stipes Pub. Co.: page 667

Dirr, M. (1997). Dirr’s hardy trees and shrubs: An illustrated encyclopedia. Portland, Or: Timber Press.

Stewartia pseudocamellia (deciduous camellia)

Volunteer Spotlight: Growing with Children at Camp Discovery on Webb Pond

By Rose Ann Schultz, Master Gardener Volunteer

This Master Gardener Volunteer (MGV) project began in the summer of 2017 as a collaboration between Down East Family-YMCA Summer Day Camp and the Hancock and Washington Counties MGV program. There’s much to be proud of already after only a few seasons of growth.

The approximately 3,000-square-foot garden is in an open field about 1/4 mile from the main camp buildings. Following soil test report recommendations, the ground was amended with wood ash and other organic amendments to bring the soil to near optimum growing conditions.

With support from various businesses and organizations, the garden received a significant boost in 2018. Viking Lumber (Hancock) donated hemlock boards that were used to construct raised garden beds filled with loam and compost donated by Eagle Arboriculture (Trenton). The Maine Master Gardener Development Board awarded a $500 grant in 2018 that aided in the purchase of fertilizer, composted goat manure, and equipment for fresh water storage on site. As a result, the garden yielded 430 pounds of fresh organic produce that was distributed almost evenly to the camp kitchen, one local food pantry, and two local meal sites.

Campers of all ages come to the garden on scheduled visits to work in the raised beds planting seeds and seedlings, watering, and weeding. They are guided by MGVs in the harvesting of produce grown in the raised and in-ground beds.

Benefits to campers and their parents:

- Youth begin to dream about how they could use vegetables and herbs to build their own salad creations. They’re often inspired to grow their own food in a home garden.

- Participants recognize that the tomatoes, peppers, and cilantro that are grown in this garden can be used to make salsa and begin to comprehend where their food comes from and the importance of gardening.

- Cabbage that campers help to harvest from the garden becomes cole slaw served at lunchtime at the camp kitchen, making the food “taste better.”

- Picking and eating the fresh snap peas and beans is a real treat. Youth learn that fresh veggies make a great snack and parents find that it becomes easier to get kids to eat more healthy snacks.

- Campers also learn the importance of sharing food with neighbors in need. This program gives them the opportunity to be in the position to help others.

So, what does it take to make the Camp Discovery Organic Garden successful? In the 2018 growing season (April through October), five master gardeners logged 245 volunteer hours. In addition, Camp Director Roman Perez along with Assistant Camp Director Christopher Edie spent many hours tending and watering the garden. A camp counselor was assigned to assist campers with planting and watering the garden.

Benefits to camp staff and Master Gardener Volunteers:

- Camp staff can offer a unique learning experience with this hands-on gardening activity.

- Camp staff can offer a beneficial outlet for the enthusiasm and energy that campers have during the summer.

- Staff have the opportunity to learn new gardening techniques from MGV.

- MGV have an opportunity to explore new garden techniques and vegetable varieties.

- MGV have an opportunity to share the joy and peace they have come to know in the gardening experience, eating healthy produce, and sharing the bounty of the earth.

As we enter our third season of growing with children at Camp Discovery, we’re excited by a new goal this year: the garden will aim to deliver fresh produce (plum tomatoes, onions, and delicata squash) for the UMaine Extension Eat Well program for use in cooking demonstrations and taste tests at area food pantries. It’s exciting to see the transformation that has taken place and consider the individuals impacted by this project in such a short amount of time.

Contact Information:

Downeast Family – YMCA

Camp Discovery on Webb Pond

120 Silver Hill Farm Road

Eastbrook, ME 04634

University of Maine Cooperative Extension

Hancock and Washington Counties

The Maine Master Gardener Development Board supports numerous volunteer projects throughout the state. Please consider making a contribution today!

Food & Nutrition: The Missing Ingredient: Adherence of Food Blog Salsa Recipes to Home Canning Guidelines

By Kathy Savoie, MS, RD, Associate Extension Professor, UMaine Extension Cumberland County

Increased interest in home food preservation, the popularity of home canning salsa, and the emergence of food blogs as an easily accessible source for recipes has created concerns about the safety of home canning recipes on food blogs. How safe are the salsa recipes found on popular food blogs? According to a new research study by the University of Maine Cooperative Extension, there are a lot of issues to be concerned about related to salsa recipes on food blogs—mostly what isn’t there.

The research study, “Adherence of Food Blog Salsa Recipes to Home Canning Guidelines,” by UMaine Extension Professor Kathy Savoie and Jen Perry, UMaine Assistant Professor, found that the majority of USDA home canning guidelines were not included in food blog recipes, an average 70% across all four categories analyzed, representing an overwhelming lack of adherence and cause for food safety concerns.

“Traditionally, salsas are mixtures of low-acid foods, such as onions and peppers, with acidic foods, such as tomatoes. Depending on ingredient ratios, the natural acidity of salsa mixtures may not be high enough to safely process in a boiling water bath, which is still the most common method for canning in American homes,” says Savoie, who has been providing home food preservation education since 1996. Historically, home-canned vegetables have been the most common cause of botulism outbreaks in the United States. Two recent botulism outbreaks in 2015 and 2018 involving improperly home canned foods demonstrate that this risk continues, as well as the need for continued education to those who want to preserve foods at home.

“Traditionally, salsas are mixtures of low-acid foods, such as onions and peppers, with acidic foods, such as tomatoes. Depending on ingredient ratios, the natural acidity of salsa mixtures may not be high enough to safely process in a boiling water bath, which is still the most common method for canning in American homes,” says Savoie, who has been providing home food preservation education since 1996. Historically, home-canned vegetables have been the most common cause of botulism outbreaks in the United States. Two recent botulism outbreaks in 2015 and 2018 involving improperly home canned foods demonstrate that this risk continues, as well as the need for continued education to those who want to preserve foods at home.

The researchers created a tool based on the USDA Complete Guide to Home Canning for Acidified Foods to examine 56 blog posts on home canning of salsa from 43 food blogs. Adherence to guidance in the following four categories were measured: acidification, thermal processing, contaminants, and vacuum sealing. Alarmingly, analysis of acidification volume to tomato volume revealed that 12 (21%) of the 56 recipes failed to even meet the minimum USDA acidification guidelines for tomato volume alone. Of the blogs evaluated for this study, the number of Facebook followers ranged from 719 to 3,256,656 with an average of 145,953. Additional areas of concern include:

- Only five recipes (9%) actually contained sufficient quantities of acid to account for the volume of vegetables used.

- Very few (14%) provided information regarding necessary adjustments for altitude.

- Although more than half of recipes (34, or nearly 61%) correctly specified the length of time to process jars in a boiling water bath, only ten (29%) of these indicated that processing time should start after a rolling boil is achieved, representing a critical risk of under-processing.

- Only four (7%) of the 56 recipes reviewed provided correct information on all of the following three measures: total processing time, when to start processing time and altitude adjustment.

- Only eight (14%) specified the correct type and strength of acid(s) to ensure safety.

- The mean acidification ratio across all recipes in this study was 0.94 tablespoons per cup of peppers and onions, less than half the recommended level to ensure safety during extended anaerobic storage.

So, what can a home canner do to ensure that they are making salsa safely at home?

- Access resources from USDA, UMaine Extension, and the National Center for Home Food Preservation to know the latest techniques and guidelines to safely preserve foods at home.

- Make sure that you are using recipes that have been tested to ensure that the salsa is properly acidified to ensure safety.

- When searching the web, search for accurate, science-based information by typing site:.edu at the end of your query term. This will help to direct your search towards educational institutions. You can use the same strategy and to search for government information, ending your query with site:.gov. For example, search “canning salsa site:.edu”.

Resources for Safe Home Food Preservation: UMaine Cooperative Extension publications, including the USDA Complete Guide to Home Canning and So Easy to Preserve

UMaine Cooperative Extension upcoming workshops: Food Preservation Hands-On Workshops

National Center for Home Food Preservation Salsa recipes: National Center for Home Food Preservation

For more information on the research study, contact Kathy Savoie at ksavoie@maine.edu.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications fill out our online form.

For more information or questions, contact Kate Garland at katherine.garland@maine.edu or 1.800.287.1485 (in Maine).

Visit our Archives to see past issues.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around Maine, with Katherine Garland, UMaine Extension Horticulturalist in Penobscot County, serving as editor.

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2019

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

The University of Maine is an EEO/AA employer, and does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender expression, national origin, citizenship status, age, disability, genetic information or veteran’s status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Sarah E. Harebo, Director of Equal Opportunity, 101 North Stevens Hall, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5754, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).