Maine Home Garden News — August 2021

In This Issue:

- August Is the Month to . . .

- Protect Your Yard and Garden from Deer

- Crazy Worms in Maine

- Why Can’t I Grow Gooseberries and Currants in Maine?

- Harvest Hints

- Reader Exchange: Got Sun?

- Stay in the Loop with What’s Happening with Maine’s Trees

August Is the Month to . . .

By Will Larson

- Dry flowers: August is a good time for collecting flowers, foliage, and seed heads for floral arrangements. A simple method for drying is to wrap a bundle of stems together using rubber bands and suspend the bunch upside down. Warm, well-circulating air will dry the cut flowers quickly. Flowers that dry well include bachelor’s button (Centaurea cynaus), globe amaranth (Gomphrena globosa), and anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum), while poppies (Papaver spp.), mullein (Verbascum spp.), and honesty (Lunaria annua); all provide interesting seed heads to an arrangement. See Drying Flowers and Foliage for Arrangements from University of Missouri Extension or this group of articles from Cornell Cooperative Extension for more information.

- Order bulbs and plan nursery orders: Now is the time to be ordering your bulbs ahead of fall planting; many suppliers accept orders through the end of August. Spring-flowering bulbs, such as crocuses and daffodils, are suitable for planting in September and October, giving a few weeks for the bulbs to root in before the ground freezes. Many mail-order nurseries begin to ship live plants again in September, so compiling a wish list for the garden ahead of time can ensure you have the plants you want to put in the ground come fall.

- Sow cover crops: Cover crops are a great option for any garden with empty space. They can suppress weeds, benefit pollinators, and provide nutrients to the soil when incorporated as a green manure. Cover crops such as winter rye can be sown in August and will continue to grow in the spring. Since they are winter-hardy they will need to be incorporated into the soil with a tiller prior to planting desired crops the following spring. Fall plantings of winter-killed cover crops, such as tillage radish or oats, can be dug into a bed with a fork or spade in the spring or simply left in place to break down and serve as a short-term mulch for the early part of next spring. For more information about cover cropping, see UMaine Extension Bulletin #1170, Cover Cropping for Success, or watch these videos Benefits of Cover Cropping and Planning for Your Cover Crop, and consult these tables for seeding rates and times for different cover crops.

- Deadhead and collect seeds: Most plants will continue to bloom well into the fall as long as you remove spent flower heads. If you don’t shear the stems, the flower heads will often set seed (as long as it is not a sterile cultivar). Usually seeds are ripe when the seed head dries, changes color (often from green to brown), and splits open; the seeds will also generally darken in color as they ripen. Seed propagation can be exciting, particularly if you grow multiple compatible species or varieties that may interbreed and hybridize to produce new and interesting offspring. Columbines (the genus Aquilegia) are famously interfertile, and there are many other popular garden plants (like violas and echinaceas) that readily produce hybrid forms.

- Harvest, preserve, and donate tomatoes: If you find yourself with too many tomatoes, consider canning (see UMaine Extension Bulletin #4085, Let’s Preserve: Tomatoes) or donating through the Maine Harvest for Hunger program.

Protect Your Yard and Garden from Deer

By Griffin Dill, Integrated Pest Management Professional

Whether you live among Maine’s rural forests or within suburban cities and towns, you’re increasingly likely to see deer meandering across the property. While many people enjoy the opportunity to view wildlife in their own backyards, deer can cause extensive damage to gardens and home landscapes. Deer eat several hundred different types of plants in the Northeast, grazing on a variety of grasses, leaves, bark, fruits, nuts, acorns, berries, and even lichen and fungi. A single deer can consume five to ten pounds of plant material per day, including some of their landscape favorites like hostas, roses, daylilies, and yew. In addition to the damage they can cause to landscape plants, deer are also important hosts for ticks, with increased tick abundance frequently related to the presence of deer.

Whether you live among Maine’s rural forests or within suburban cities and towns, you’re increasingly likely to see deer meandering across the property. While many people enjoy the opportunity to view wildlife in their own backyards, deer can cause extensive damage to gardens and home landscapes. Deer eat several hundred different types of plants in the Northeast, grazing on a variety of grasses, leaves, bark, fruits, nuts, acorns, berries, and even lichen and fungi. A single deer can consume five to ten pounds of plant material per day, including some of their landscape favorites like hostas, roses, daylilies, and yew. In addition to the damage they can cause to landscape plants, deer are also important hosts for ticks, with increased tick abundance frequently related to the presence of deer.

Preventing deer damage in the home landscape is challenging, as deer can be persistent when they discover a nutritious and enjoyable food source. It is important to have realistic goals for reducing deer damage and to try multiple strategies to maximize your success. Some management strategies can provide long-term reductions in deer damage, while others are effective only in limited, short-term situations.

Deer-Resistant Plants

Naturally, minimizing the available food sources in the home landscape is the most effective way to prevent deer damage. If there is nothing palatable in your yard, you may simply catch a glimpse of the deer as they pass by on their way to your neighbor’s buffet. Though this can initially feel like creating a barren yard and garden, there are a wide variety of deer-resistant plants (PDF) that can add beauty to the landscape. It should be noted that even deer-resistant plants may be eaten if deer are hungry enough or if deer populations are particularly high.

Physical Barriers

For situations where deer-resistant plants are unavailable, particularly fruit and vegetable gardens, adequate fencing is the only reliable method for excluding deer. As deer are excellent jumpers, fences should be a minimum of eight feet tall to protect larger areas, though they may be slightly shorter for smaller gardens. Electric fencing is another effective option that can provide a long-term reduction in deer feeding damage. Other barriers, like cages and netting, may be appropriate for specific plants or for minimizing damage in the short-term.

Repellents

There are a wide variety of commercial and DIY deer repellents available to the home gardener, including hot pepper, rotten eggs, ammonium soaps, predator urine, human hair, and perfumed soaps to name a few. Repellents tend to be short-term solutions with limited effectiveness. To maximize their efficacy, repellents should be applied as early as possible and reapplied frequently. Repellents should also be rotated regularly to prevent deer from becoming habituated to a specific product. In addition to repellents that repel by taste or smell, other repellent options frighten deer with lights, loud noises, water, or physical objects. These types of repellents also tend to work for only short periods, as deer quickly become used to the techniques.

For More Information

For more information on deer in Maine, please visit the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife (IFW) page on living with wildlife.

Also, consider becoming a Maine Deer Spy and help wildlife biologists better understand deer population dynamics in Maine by recording and reporting your deer sightings to Maine IFW.

Crazy Worms in Maine

A re-issue of an article written by Gary Fish, State Horticulturist Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry for our April 2019 edition of Maine Home Garden News

Due to our history of glaciation, there are no native earthworms in Maine. Non-native earthworms from Europe, such as night crawlers, became well established in Maine through early colonial trading with Europe. While beneficial to gardens, earthworms are known to have destructive effects on our forests.

Crazy worms (Amynthas agrestis, Amynthas tokioensis, and Metaphire hilgendorfi) are invasive earthworms native to East Asia. Originating in Korea and Japan, the crazy worm is now found from Maine to Florida and west to Texas. Although first collected from a Maine greenhouse in 1899, an established population of this active and damaging pest was not discovered until 2014 when populations were discovered at the Viles Arboretum in Augusta, one other Augusta location, and two Portland sites. We believe crazy worms are not yet widespread here, but they have been discovered in many new locations since 2014, including in compost, manure, and nursery settings. If allowed to spread, crazy worms could cause serious damage to horticultural crops and forest ecosystems in Maine. It is illegal to import them into Maine (or to propagate or possess them) without a wildlife importation permit from the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife (MDIFW). For more information, visit the MDIFW’s Fish & Wildlife in Captivity webpage.

Crazy worm basics

The name speaks for itself! When handled, they act crazy, jump and thrash and behave more like a threatened snake than a worm. Further, they may shed their tails when caught. Crazy worms can be 1.5 to 8 inches long. They also move rapidly on top of the soil.

The narrow band around their body (clitellum) is milky white and smooth and much closer to the head than on nightcrawlers, unlike other species that have a raised clitellum (see photo). Crazy worms reproduce easily. They are asexual (parthenogenetic) and mature in just 60–90 days, so some years they can have two hatches. The best time to find them is late June to mid-October. From September until the first hard frost, their population will double and may reach damaging levels. In nursery settings, they can often be found underneath pots that are sitting on the ground or on landscape fabric. In forests, they tend to be under accumulations of slash or duff.

What’s the problem?

There are reports from homeowners in Connecticut who blame the abundant castings of this earthworm for the demise of their lawns. In Vermont, some Master Gardeners associate the appearance of this species with the loss of ephemeral beds. Crazy worms have been linked with several reports of deleterious effects on horticultural crops. In one case that made the press a few years ago, a hosta producer in Pennsylvania lost most of his crop to crazy worms.

Crazy worms change the soil by accelerating the decomposition of leaf litter on the forest floor. They turn good soil into grainy, dry worm castings (poop) that cannot support the understory plants of our forests. Over time the soil also becomes compacted. Other plants, animals, and fungi disappear because the understory community can no longer support them. As the understory plants disappear, invasive exotic plants may take their place and further exacerbate the loss of plant species diversity.

In nurseries and greenhouses, crazy worms reduce the functionality of soils and planting media and cause severe drought symptoms. After irrigation or rains, crazy worms may be found under pots. Crazy worms can be inadvertently moved with nursery stock in soil or in mulch and compost.

More than other earthworms, crazy worms have a voracious appetite, speedy life cycle, and a competitive edge. Crazy worms tend to outcompete the other earthworms and soil microbiota where they’re established. They may cause long-term harm to the forests of Maine, which are already under pressure from other invasive insects, plants, pathogens, and diseases. We need to slow the spread of crazy worms in Maine to help reduce the threat to Maine’s natural communities.

Crazy worm best management practices

- Do not buy or use crazy worms for composting, vermicomposting, gardening, or bait.

- Do not discard live worms in the wild; dispose of them in the trash (preferably dead).

- Check your plantings; know what you are purchasing and look at the soil.

- Buy bare root plants when possible.

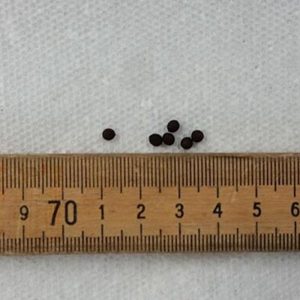

- Be careful when sharing or moving plantings; tiny earthworm cocoons (3 mm diameter) may be in the soil (see photo above).

- Map it! Please visit the DACF iMap Invasives web page for more information

- Questions? Call Gary Fish 207.287.7545 or email gary.fish@maine.gov.

For more information, visit the DACF website.

Why Can’t I Grow Gooseberries and Currants in Maine?

Information compiled from the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry (DACF) websites (listed at the end) with significant contributions from Allison Kanoti, State Entomologist with the Maine Forest Service, Forest Health and Monitoring, DACF

White pine blister rust, caused by the fungus Cronartium ribicola, was introduced into the U.S. around 1900 and has since spread throughout the range of white pine. This disease causes mortality and severely reduces the commercial value of eastern white pine (Pinus strobus). The rust fungus cannot spread from pine to pine but requires an alternate host, Ribes species (currants and gooseberries, collectively called “ribes”), to complete the disease cycle.

In an effort to manage the spread of white pine blister rust, the state of Maine has had a long-standing quarantine on currants and gooseberry bushes. The rule states, “The sale, transportation, further planting or possession of plants of the genus Ribes (commonly) known as currant and gooseberry plants, including cultivated, wild, or ornamental sorts is prohibited in the following counties in the state of Maine: York, Cumberland, Androscoggin, Kennebec, Sagadahoc, Lincoln, Knox, Waldo, Hancock, and parts of Oxford, Franklin, Somerset, Piscataquis, Penobscot, Aroostook, and Washington (map (PDF | 1.4 MB), list of towns (PDF | 547 KB). The planting or possession of European Black Currant, Ribes nigrum, or its varieties or hybrids anywhere within the boundaries of the State of Maine is prohibited.”

In 2019, mills in Maine paid landowners about 33 million dollars for white pine saw logs, according to data from wood processor and stumpage reports compiled by the Maine Forest Service. Many Maine farmers benefit from this resource, as harvested forest acreage is a frequent feature of farms in Maine. It’s estimated that contractors receive an equal amount or more, so at least 66 million dollars between loggers and landowners for sawlog products. This does not take into account lower-grade products or the impact to the economy of the value-added products from these native trees. A recent publication from UMaine states “conservative estimates of the value of white pine trees in Maine’s forests exceed $2 billion.”

White pine is increasing in Maine and we expect it to be one of the species that is able to prevail in a changing climate. Over the ten years between 2008 and 2018, the Forest Inventory reported an increase from 473.5 Million stems to 530.5 million stems statewide. This species has the highest concentration in southwestern Maine, but also has high volumes in Downeast Maine.

Resistance and immunity to the fungus that causes white pine blister rust, Cronartium ribicola, is not reliable. A strain of C. ribicola, identified in late 2010, is now known to be able to infect previously resistant and immune species and cultivars of Ribes. A study was completed in 2014 by the USDA Forest Service to determine the effects of this new strain of C. ribicola on Ribes and the white pine hosts in New Hampshire. The presence of C. ribicola was confirmed on 17 of the 19 ‘immune’ or ‘resistant’ Ribes cultivars screened. The study also reported an 18 percent probability of finding white pine blister rust on pines neighboring black currants that were infected with the new pathogen strain, but only a 2 percent probability of finding the rust on pines neighboring pathogen-free Ribes. The difference was highly significant both statistically and epidemiologically. Read the full report. Work just completed by a PhD candidate at Antioch University of New England points to increasing presence of white pine blister rust and a longer sporulating period of the fungus.

This quarantine is administered by the Maine Forest Service, Forest Health and Monitoring Program. For more information about this and other quarantines, phone 207.287.2431 or visit:

Harvest Hints

Knowing the ideal time to harvest crops is essential to getting the highest-quality produce and, for storage crops, the longest shelf life. Here are some terrific resources to help you make good harvesting decisions this season:

Knowing the ideal time to harvest crops is essential to getting the highest-quality produce and, for storage crops, the longest shelf life. Here are some terrific resources to help you make good harvesting decisions this season:

- Correct Stage to Harvest Melons

- How to Harvest and Store Onions

- Pumpkin Harvesting and Storage

- How to Harvest and Store Apples

- Harvesting Garden Produce (food safety tips)

Remember, we also have an extensive collection of food preservation and cooking resources regularly featured on our new “Spoonful” blog.

Reader Exchange: Got Sun?

A community garden in Dexter had the challenge of not having a speck of shade where the team could rest and cool off. To address the problem, gardeners created a hops shade structure that is both beautiful and functional, with a view of the gardens to boot. The hops plant is a hardy herbaceous vine that grows very easily in our region. Learn more about growing hops.

Our readers have a lot of experience and great ideas. Therefore, we decided it’s high time you chimed in with some of your favorite gardening tips and tricks. Each month, we’ll challenge you to send us gardening “hacks” that make your horticultural life more fun and productive. If your submission is selected, we’ll provide you with a free soil test with the Maine Soil Testing Service. Submit your ideas to katherine.garland@maine.edu with the email subject “Reader Exchange”.

Stay in the Loop with What’s Happening with Maine’s Trees

Mainers love their trees and are eager to find out what may be happening to their beloved forests when they notice signs of plant decline. The Maine Forest Service offers a treasure trove of information for those who wish to stay up to date on insect, disease, and even abiotic stresses that are impacting our region. Their updates are very informative and readable.

Their most recent update includes information about

- emerald ash borer

- gypsy moth

- browntail moth

- beech leaf disease

- drought

- hemlock wooly adelgid

- and more!

This information is key for anyone who is eager to play a role in protecting Maine’s forest resources. Look for the option to subscribe in the update page.

Do you appreciate the work we are doing?

Consider making a contribution to the Maine Master Gardener Development Fund. Your dollars will support and expand Master Gardener Volunteer community outreach across Maine.

Your feedback is important to us!

We appreciate your feedback and ideas for future Maine Home Garden News topics. We look forward to sharing new information and inspiration in future issues.

Subscribe to Maine Home Garden News

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications, click on the Subscribe button below.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

For more information or questions, contact Kate Garland at katherine.garland@maine.edu or 1.800.287.1485 (in Maine).

Visit our Archives to see past issues.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around Maine, with Katherine Garland, UMaine Extension Horticulturalist in Penobscot County, serving as editor. Special thanks to our 2020 Master Gardener Volunteer co-editors Naomi Jacobs and Abby Zelz.

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2021

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

The University of Maine is an EEO/AA employer, and does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender expression, national origin, citizenship status, age, disability, genetic information or veteran’s status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Director of Equal Opportunity, 101 North Stevens Hall, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5754, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).