Maine Home Garden News — January 2022

In This Issue:

- January Is the Month to . . .

- Sightings: Vole Runways

- Evening Grosbeak

- A Review of The Earth Knows My Name: Food, Culture, and Sustainability in the Gardens of Ethnic Americans by Patricia Elindienst (Beacon Press, 2006)

- Wabanaki Writings

- Reader Exchange

January Is the Month to . . .

By Kate Garland, Horticulturist, UMaine Extension Penobscot County

- Be mindful while using salts to melt driveway and walkway ice. Plants in gardens along walkways often get hit especially hard, with salt toxicity symptoms ranging from mild tip burn to complete dieback. De-icing salts are also linked to ground and surface water pollution that can impact a variety of aquatic species.

Participate in the Maine Winter Bird Atlas, a project by the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife to document the breeding and wintering distributions of Maine’s birds. You don’t need to be a birding expert to get involved, and every reported sighting helps!

Participate in the Maine Winter Bird Atlas, a project by the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife to document the breeding and wintering distributions of Maine’s birds. You don’t need to be a birding expert to get involved, and every reported sighting helps!

- Consider selecting disease-resistant varieties when ordering seeds and plants. Using resistant varieties to minimize disease pressure is an inexpensive and easy first line of defense in a home garden Integrated Pest Management plan. Look to the New England Vegetable Management Guide, UMaine Extension small fruit fact sheets, and Growing Fruit Trees in Maine for disease-resistant varieties.

- Take care of unsafe limbs and trees sooner than later. New issues can pop up more regularly during the winter storm season. Reach out to a licensed arborist for help managing limbs that are out of your comfort zone, especially those near power lines.

- Gather supplies for starting seeds indoors, but don’t dig in just yet. Starting seeds too early is one of the most common missteps people make when they first attempt to grow their own seedlings. Now is the time to prep your space and mark your calendar for the optimal time to start each type you plan to grow.

Keep amaryllis plants in a sunny window and remove only the spent flowers at the top of the flower stalk. The green flower stalk and leaves should be left alone so they can continue to photosynthesize and support continued growth for future blooms next winter.

Keep amaryllis plants in a sunny window and remove only the spent flowers at the top of the flower stalk. The green flower stalk and leaves should be left alone so they can continue to photosynthesize and support continued growth for future blooms next winter.

- Learn. Take advantage of our upcoming live webinars, on-demand webinars (listed below), and Victory Garden for ME videos that are available anytime! Our new on-demand webinars are packaged in bundles of 3 to 4 pre-recorded webinars along with a curated list of resources for each topic.

Sightings: Vole Runways

Sightings: Vole Runways

There’s a lot still happening under that layer of snow and ice in your landscape. Thanks to Christopher D’Amico for this great picture showing evidence of vole activity at a home landscape in central Maine. Voles can cause a significant amount of damage to young woody plants and are especially troublesome in newly planted orchards.

Visit the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry’s “Got Pests?” website to learn more about vole biology and find a great compilation of management resources.

Evening Grosbeak

By Doug Hitchcox, Maine Audubon Staff Naturalist

Historically restricted to the western half of this continent, Evening Grosbeaks have expanded eastward thanks to the food they found here. Evening Grosbeaks are large finches, and like other finches will often have irruptions in winter, meaning they’ll leave their typical range when food is scarce. Thanks to the abundance of (unfortunately non-native) Box Elder and cyclically abundant Spruce Budworm, these grosbeaks have established themselves in the east and have become a colorful visitor to our yards and feeders in the winter. Despite the damage that Spruce Budworms do to trees, they are a native insect and an important food source for grosbeaks and a number of other species that nest in the boreal forest. It was during the budworm’s last outbreak in the 80s that we recorded an Evening Grosbeak population boom, though numbers have dwindled since. More recently, budworm abundance has been increasing and it’ll be fun to watch if the large black, white, and yellow Evening Grosbeaks become common around our yards again.

For more on the importance of Maine native plants to support birds and other wildlife, visit Maine Audubon’s “Bringing Nature Home.”

- Evening Grosbeak (female). Photo by Doug Hitchcox.

- Evening Grosbeak (male). Photo by Doug Hitchcox.

A Review of The Earth Knows My Name: Food, Culture, and Sustainability in the Gardens of Ethnic Americans by Patricia Elindienst

(Beacon Press, 2006)

Reviewer: Abby Zelz, Penobscot County Master Gardener Volunteer

The Earth Knows My Name: Food, Culture, and Sustainability in the Gardens of Ethnic Americans takes readers on a cross-country tour, stopping at a variety of farms and gardens to meet with people and talk to them about their family stories and gardens.

Elindienst visits 15 gardens tended by people of different backgrounds. She travels to New Mexico, South Carolina, California, Washington state, and New England to walk through the fields and gardens and talk to the people who tend them. The gardeners’ ethnic groups and traditions include Native American, Hispanic, Gullah, Japanese, Cambodian, Italian, Punjabi, and others.

The author blends the gardeners’ thoughts about tending the earth with their immigration stories, placed within the broader context of U.S. history. These are a diverse group of gardeners, young and old, working in small urban community garden plots, a vineyard, a single crop farm, and large cultivated areas. She learns how their gardening choices are informed by their cultural heritage as well as the need for sustenance, how they blend tradition with newer methods or interests, and which plants hold special meaning and tie them to their culture. The challenges of each group range from the uncertainty of the weather to soil conditions and economic pressures. On Bainbridge Island, off Seattle, for example, a vineyard and a berry farm struggle to survive as skyrocketing land values impose rapidly increasing taxes.

For those who tend the land, gardening connects them to their cultural traditions and provides some independence. Although assimilation into mainstream American culture has diminished or erased traditional language, religion, or dress, the opportunity to grow food reflects a cultural memory and sometimes even expresses a bit of resistance to the homogenization of mainstream American culture.

Loretta Fresquez of New Mexico left her desk job to farm, observing, “We’re making an honest living doing something we truly enjoy from the heart. We’re teaching other people the importance of good food . . . And we’re keeping our heritage by keeping our food.”

Another planter Elindienst meets is Ralph Middleton, a Gullah elder on St. Helena Island in South Carolina. “Lose the land and you lose the culture” he observes. Middleton’s cultivated land has been in his family since 1866, a legacy of independence for freed slaves. The seventh generation of Gullah planters tends gardens of peas, potatoes, peanuts, collards, watermelon, and other crops, which bear similarities to the provision gardens of their enslaved ancestors. One Gullah elder notes that he hasn’t had to purchase seeds in about three decades, because he has saved seeds each year. The author contrasts these traditional Gullah gardens with the adjacent commercial single-crop tomato fields on St. Helena, which are tended by Mexican migrant workers, and use mechanical irrigation and chemical fertilizers.

The growers’ personal stories about caring for the soil, pride in sharing the harvest, and the sense of purpose that gardens provide complement each other as beautifully as the three sisters — corn, beans, and squash — grow together in a Pueblo garden.

For both new residents of the U.S. and those with deep roots, this volume reveals common threads among gardeners. Learning from these diverse gardeners’ stories and visiting their lush fields and gardens, abundant with ripening vegetables, fragrant herbs, and vibrant flowers may provide not only food for thought but also an inspiration for spring projects.

Wabanaki Writings

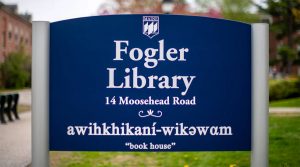

In honor of the university’s place in Penobscot Nation homeland, the Fogler Library staff created, and are continually updating, a list of books, and sections of books, by Wabanaki authors. These are all available through awihkhikaní-wikəwαm (“book house,” or “Fogler Library,” in the Penobscot language) and may be available through your local library through interlibrary loan. Click here to see the list and reach out to your local library for questions on how to access these resources. Please contact Jen Bonnet (jenbonnet@maine.edu or call 207.581.3611) with any suggestions, corrections, and/or feedback.

In honor of the university’s place in Penobscot Nation homeland, the Fogler Library staff created, and are continually updating, a list of books, and sections of books, by Wabanaki authors. These are all available through awihkhikaní-wikəwαm (“book house,” or “Fogler Library,” in the Penobscot language) and may be available through your local library through interlibrary loan. Click here to see the list and reach out to your local library for questions on how to access these resources. Please contact Jen Bonnet (jenbonnet@maine.edu or call 207.581.3611) with any suggestions, corrections, and/or feedback.

Reader Exchange

Our readers have a lot of experience and great ideas. Therefore, we decided it’s high time you chimed in with some of your favorite gardening tips and tricks. Each month, we’re challenging you to send us gardening “hacks” that make your horticultural life more fun and productive. If your submission is selected, we’ll provide you with a free soil test with the Maine Soil Testing Service. Submit your ideas to katherine.garland@maine.edu with the email subject “Reader Exchange”.

Do you appreciate the work we are doing?

Consider making a contribution to the Maine Master Gardener Development Fund. Your dollars will support and expand Master Gardener Volunteer community outreach across Maine.

Your feedback is important to us!

We appreciate your feedback and ideas for future Maine Home Garden News topics. We look forward to sharing new information and inspiration in future issues.

Subscribe to Maine Home Garden News

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications, click on the Subscribe button below.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

For more information or questions, contact Kate Garland at katherine.garland@maine.edu or 1.800.287.1485 (in Maine).

Visit our Archives to see past issues.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around Maine, with Katherine Garland, UMaine Extension Horticulturalist in Penobscot County, serving as editor. Special thanks to our Master Gardener Volunteer co-editors Naomi Jacobs and Abby Zelz.

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2022

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

The University of Maine is an EEO/AA employer, and does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender expression, national origin, citizenship status, age, disability, genetic information or veteran’s status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Director of Equal Opportunity, 101 North Stevens Hall, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5754, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).