Maine Home Garden News March 2023

In This Issue:

- March Is the Month to . . .

- Food for thought: How a Thomaston teacher and a Master Gardener Volunteer created a community garden for 8th graders

- Farm City: The Education of an Urban Farmer by Novella Carpenter (2009 pp. 269)

- Taming the Seed Madness

- Backyard Bird of the Month: Carolina Wren

- Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry: Visit Some Beeches

March Is the Month to . . .

By Barbara Harrity, Penobscot County Master Gardener Volunteer

Order seeds.

Order seeds.

If you’re planting a vegetable garden this year and haven’t yet ordered seeds, you’ll want to get your order in soon. Bulletin #2190, Vegetable Varieties for Maine Gardens has suggestions on some reliable varieties for Maine gardens. If you usually buy annuals and perennials from a garden center, you may be surprised at the interesting flower seeds available from seed companies, flower varieties, or colors that might be hard to find at your local garden center or nursery.

Start your own seedlings.

See Bulletin #2751, Starting Seeds at Home for information about supplies and growing conditions. The bulletin includes a video that offers a comprehensive overview of the topic as well as a video describing how to make a seedling stand.

Here’s a list of some plants that should be started by seed indoors this month.

- Early to mid-March: celery, celeriac, leeks, parsley, peas, delphinium, butterfly weed (Asclepias), foxglove (Digitalis), sweet William (Dianthus), and pansy (Viola).

- Mid to late March: cabbage, collards, kale, kohlrabi, lettuce, mustard, angel’s trumpet (Datura), yarrow, verbena, stock, snapdragon, black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia), petunia, hollyhock, and blanket flower.

- Late March to early April: artichoke, beets, broccoli, cauliflower, eggplant, swiss chard, ageratum, sweet annie (Artemisia), aster, calendula, bachelor’s buttons (Centaurea), globe amaranth (Gomphrena), larkspur, bee balm (Monarda), phlox, Iceland poppy, statice, strawflower, sweet pea.

*In coastal Maine, plant 10-14 days earlier. In northern Maine, plant 10-14 days later.

Make paper pots.

Consider using newspaper pots for your seedlings — they’re easy to make and biodegradable. Here’s a video, DIY Newspaper Plant Pots, showing how to make different types of paper pots. If you don’t receive the newspaper at home, check with your neighbors who may have some in their recycling bins. Or take it a step further and subscribe to a local newspaper. Maine is fortunate to have a great selection of daily and weekly local newspapers, but as with our gardens, these newspapers need our support to thrive.

Prune select woody plants.

March is a great time to put those freshly sharpened pruners to work because it’s easy to see where branches are crossing, damaged, or dead. For more information, check out UMaine Cooperative Extension Bulletin #2169, Pruning Woody Landscape Plants.

Sample local maple syrup.

Sample local maple syrup.

Maine Maple Sunday Weekend is on March 25 and 26 this year. As part of this family-friendly event, you can visit local sugarhouses and sample local maple syrup. Many farms also offer a variety of activities throughout the day. If you have sugar maple (Acer saccharum) trees on your property, you can also try tapping and making your own syrup, see Bulletin #7036 How to Tap Maple Trees and Make Maple Syrup. The Forest Trees of Maine can assist you with identifying maple trees on your property in both summer and winter.

Join a garden club.

To expand your knowledge and skills and meet others who are interested in gardening consider joining a local garden club. A list of many Maine garden clubs with contact information is available at the Garden Club Federation of Maine.

Catch a webinar.

Join the University of Maine Cooperative Extension for our gardening webinar series starting later this month. These one-hour and 15-minute webinars will include a 1-hour presentation followed by Q&A and discussion. Topics include: Healthy Gardens Start with Healthy Plants; Growing Great Tomatoes, Peppers, Melons and More; and Beyond the Apple: Growing Unique Fruit in Maine.

Knockout browntail moth.

The window is closing on the optimal time to clip webs (Oct-mid April). Learn more, Browntail Moth, and don’t wait!

Enjoy the rapidly lengthening days.

Most places in Maine gain about 3 minutes of daylight a day during March, with overall daylight lengthening from around 11 hours on March 1 to more than 12.5 hours on March 31.

Food for thought: How a Thomaston teacher and a Master Gardener Volunteer created a community garden for 8th graders

By Shelby Hartin, Penobscot County Master Gardener Volunteer

In 2018, Catherine Sally, an 8th-grade English language arts teacher at Oceanside Middle School (OMS) in Thomaston, took a sabbatical, leaving Maine for California. Her purpose was twofold. First, she was deciding whether to move away from Maine. This trip was going to help with that decision. Second, and perhaps most important, she began volunteering in Berkeley, where all of their schools have a gardening and cooking curriculum.

“I volunteered in two schools and thought it was a perfect thing for middle school students,” Sally said.

Her mind was made up.

“When I came back, I said, ‘I’m going to start a garden at school.’ Am I a gardener? No, not at all, but I love playing in the dirt.”

In 2019 Sally got to it, first working with her students to write letters to the superintendent and the town to receive permission to clear the area where the garden would be: a spot near the soccer field. There were three raised beds from an old plot that Sally and her team of 8th graders then moved to their new home before building three additional beds. The pandemic then brought the project to a halt as schools closed and students adjusted to virtual learning. Fortunately, in fall 2020 Sally and her students were back in the garden.

Now, nearly four years after the work first began, the OMS Community Garden has grown to 26 beds, a garden shed, a hoop house, three compost bins, picnic tables and benches, and even a couple rain barrels. This is where Sally incorporates gardening into her curriculum – with help from a Master Gardener Volunteer.

Tiare Messing, a retired teacher and graduate of the 2021 Master Gardener Volunteer program through the University of Maine Cooperative Extension, was looking for projects to work on when Liz Stanley, a Horticulture Community Education Assistant at the extension, gave Messing a couple options for volunteering at local schools. Messing began reaching out, hoping she would get a response.

“Catherine answered,” Messing said. “It combines two of my favorite things to do: working with kids and working in the garden.”

In 2021, Messing assisted with many of the logistics, helping Sally plan out the garden and what would be in it. It was an experimental year, but that experiment blossomed into a varied approach to learning.

In 2022, and now again in 2023, Sally has used the garden in her curriculum, starting with two books, A Long Walk to Water by Linda Sue Park and Inside Out and Back Again by Thanhha Lai. The students read the books and learn about the cultures and people discussed in each. They then research their own heritage, diving into customs, celebrations, and, you guessed it, food. The students then decide what they want to plant in the garden based on their studies, from lemongrass to tomatoes to beets.

In addition to this lesson plan, Sally had her students start their own seedling business, designing a brochure, taking orders, and planting seeds that they deliver once they’re grown and ready to be transplanted. In 2022 they grew 1,500 seedlings.

Sally admitted that she found the community garden project stressful at first, mainly from wanting things to go well (and grow well). She was soon learning lessons of her own, though.

“I think for me, sometimes it’s really stressful, but sometimes when I’m in a raised bed and I’m pulling weeds with the kids, it’s just having that connection with them that you don’t have in the classroom. A lot of kids open up more for some reason when they’re out digging in the dirt. You build better relationships with the students doing it,” Sally said.

“One of my favorite memories was from summertime,” Messing added. “We don’t have a lot of kids that show up then because school is out, but we had two or three girls who came every week. They wanted to figure out how to identify the wild plants growing on the edge of the field. We had a week where I brought my plant identification book and they had their cell phones and we had a competition to see who could identify things first, the book versus the technology.”

As for the future of the project, Sally hopes that word will spread throughout the community. She wants people to come pick things to bring home for dinner, and she wants the community to know that the space is there for them. Sally and her students give all of the fruits of their labor away for free from a vegetable stand in front of the school.

Perhaps most importantly, Sally and Messing find joy in the garden, and hope that this project will do the same for students.

“I started gardening when I won a geranium at the school fair in the 3rd grade. It’s been a source of enjoyment for me for my life. I think it will be important to a few, and that’s the important thing,” Messing said.

“I was not in a happy place with my life, and I decided to tear up my yard and start a very large garden,” Sally said. “It was almost like therapy for me, creating this huge garden. It brought me back to happiness. I thought if it did that to me, imagine what working in a garden or doing something physical like this, the impact it might have on a student.”

To learn more about the OMS Community Garden, you can contact Catherine Sally at email csally@rsu13.org and Tiare Messing. Like on Facebook: (OMS Community Garden)

Farm City: The Education of an Urban Farmer. by Novella Carpenter

(2009 pp. 269)

Review by Clara Ross, Penobscot County Master Gardener Volunteer

Novella Carpenter grew up with her “hippie” parents on a farm in Idaho. That farm never did take off, but Novella learned to enjoy nature. Later, she went to college and earned a degree in journalism with some courses taught by Michael Pollan. In her memoir Farm City, Novella put her passion for writing to use.

Novella moved with her partner, Bill, to a part of Oakland, California, which she referred to as a “ghetto.” There they noticed a small vacant lot (a place to grow edibles?) next to their affordable second-floor apartment. She figured that the city code people would be too busy with the typical issues of managing urban communities to bother with her farming activity. So, after clearing out the lot’s refuse, repairing the soil, then growing vegetables, Novella added animals to the mix. That is when things became interesting. One scene: to feed their two small pigs, Novella and Bill went to Berkeley to raid the “finer” dumpsters. They spent a while hauling out fish guts (pigs need high protein) when a houseless man offered his last dollar bill to “poor” Novella and Bill. At the dumpster of a three-star restaurant, they met the chef who eventually taught her the fine art of making specialty meats from pigs, such as salami and prosciutto. These are among the many vignettes in this book.

The author wrote of her experiences with this city farm because she soon found out about the many folks who were also urban farming in a variety of ways. She realized that an agrarian movement was in the making and it would be important to write about it. In an outrageously entertaining and humorous manner, Carpenter wrote of her experiences in a non-preachy way. She told of raising bees; conserving water; slaughtering and butchering animals she had raised; and teaching youth from low-income communities. She discovered that in this neighborhood of many ethnic groups, no one was concerned that the rooster woke them early in the morning; her neighbors had all experienced that in their home countries around the world. While the vast majority of Maine does not come anywhere close to looking like the urbanized areas described in this book, it will likely inspire thoughts of the vast possibilities for food sustainability in your own version of “urban” Maine.

You can find this book on Kindle, audio through Cloud Library, and hardcover.

To experience the author’s personality, check out interviews on YouTube and others.

Taming the Seed Madness

By Shelby Hartin, Penobscot County Master Gardener Volunteer

Seeds were everywhere. Scattered about the bag, stuck to the sides of small white Johnny’s packets, escaping through the hole in the bottom of said bag.

“This is a problem,” I thought as I rifled through my collection. Precious time that could have been spent in the garden was slipping away minute by minute as I searched for the carrot seeds.

This scenario from last spring ran through my mind when my partner, Nate, said to me last week, “we should probably organize the seeds downstairs.” I had just placed a huge order at Johnny’s – delicata and cucumber melons and bush beans and beets – many of which were probably unnecessary because, well, I already had seeds. Lots of them. In a bag. Hiding somewhere downstairs where I had left them in disarray last year.

I sighed. “Yeah, you’re right.” He probably wouldn’t be thrilled when I did organize them and realized I already had many items I had ordered in a seed-crazy fervor that I’ll blame on the month of January. But how would they be best organized? “I’ll check out some thrift stores and look for a container of some kind,” I said. Then, like most well-intentioned plans, the idea simply left my mind. Until I stumbled across a sale at Michael’s.

No, it wasn’t the thrift store, but the colorful containers for photo storage were tagged at only $15 – down from their original $40 or so. It seemed too good to be true. I stood in front of them, considering. Each large container held 12 small containers, sized to hold 4×6 photographs– perfect for seed packets. I grabbed two sets in a rainbow assortment. “If they’re not actually on sale, I’ll just leave them,” I thought. It was quite a discount after all. A few more stops and the cash register was in sight, and lo and behold, they were actually on sale.

No, it wasn’t the thrift store, but the colorful containers for photo storage were tagged at only $15 – down from their original $40 or so. It seemed too good to be true. I stood in front of them, considering. Each large container held 12 small containers, sized to hold 4×6 photographs– perfect for seed packets. I grabbed two sets in a rainbow assortment. “If they’re not actually on sale, I’ll just leave them,” I thought. It was quite a discount after all. A few more stops and the cash register was in sight, and lo and behold, they were actually on sale.

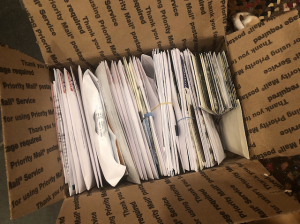

Back at home, Nate agreed that the containers would work well. He grabbed me paper, scissors, tape, and a pen for labeling and I got to work, after fetching the long-neglected and forgotten bag of seeds from downstairs. As an unexpected benefit, I also found some landscaping pins I had misplaced last spring.

I threw away empty packets, categorizing the remaining ones by type, and lamenting the fact that, yes, I had definitely ordered a bunch of new seeds that we didn’t need (oops). Regardless, the new system worked out perfectly. I was able to store all of my existing seeds, with room left over for the big order on its way. It seemed simple – maybe a couple of hours total invested in the project – but I knew it would expedite the seed starting and planting process this year.

The spring version of me will be thanking the January version for thinking ahead and taking these steps to make my life easier when it does come time to get things in the soil. Until then, what does your seed organizing system look like and will the spring version of you say the same? And where are those landscaping pins?

Editor’s note:

Shelby’s article served as just the gentle nudge I needed to get my own act together! Aiming for a zero-cost approach, I decided to use a stockpile of old strawberry clamshells and some painter’s tape to sort and label my collection. It’s much bulkier and not as attractive as Shelby’s collection, but another approach to consider. Instead of sorting by type, I took the opportunity to sort mine according to when they need to be sown. This has already made life a lot easier as I launch into the seed-starting season. We are both looking forward to hearing about your innovative approaches to taming the seed madness!

Shelby’s article served as just the gentle nudge I needed to get my own act together! Aiming for a zero-cost approach, I decided to use a stockpile of old strawberry clamshells and some painter’s tape to sort and label my collection. It’s much bulkier and not as attractive as Shelby’s collection, but another approach to consider. Instead of sorting by type, I took the opportunity to sort mine according to when they need to be sown. This has already made life a lot easier as I launch into the seed-starting season. We are both looking forward to hearing about your innovative approaches to taming the seed madness!

Backyard Bird of the Month: Carolina Wren

By Andy Kapinos, Maine Audubon Seasonal Field Naturalist

If there are Carolina Wrens in your backyard, you’ve probably already heard them. Many sing throughout the winter, they are usually one of the first to utter alarm calls in response to potential threats like hawks or cats, and male Carolina Wrens sing their loud tea-kettle songs up to eight times per minute in the morning. These small birds have spread into more and more backyards in Maine in recent decades, and have increased in abundance by 30% across much of the northern part of their range. They can be found nearly everywhere in Maine now, especially near human habitation, and have been confirmed breeding as far east and north as Ellsworth and Orono, respectively. If you hear one singing in your yard, now would be a great time to set up a wren nesting box, or you just might find one nesting in your garage or grill in a couple of months. They have been observed nesting in almost every conceivable human-made cavity, including flower pots, tin cans, broken-down cars, coat pockets, and even old shoes!

For more on the importance of Maine native plants to support birds like the Carolina Wren and other wildlife, visit Maine Audubon’s “Bringing Nature Home” webpage.

Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry News: Maine Forest Service

Visit Some Beeches During National Invasive Species Awareness Week

AUGUSTA, MAINE – The Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation & Forestry, American beech (Fagus grandifolia) illustrates the potential impacts of invasive species. Impacts from invasive species threaten the tree and the wildlife that depends on it. One invasive species has long-ravaged this tree in the northeast, and two more threaten its future.

In this new US forest service podcast, you can learn more about beech bark disease and learn about beech leaf-mining weevil in this Don’t Move Firewood blog post.

We ask you to focus on beech leaf disease on this beech excursion.

Beech leaf disease was noticed in Ohio in 2012 and first documented in Maine in 2021. We want to know where else in Maine beech leaf disease is found, and you can help.

American beech is among our native tree species with marcescent leaves. Many fail to shed all their leaves in the fall. This trait can be used to survey for beech leaf disease throughout winter. To identify potential beech leaf disease, look for dark banding between the veins of beech leaves.

Please let us know if you find beech leaf disease in a new area.

— From a media release from the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, February 25, 2023. Submitted by Kate Garland, Horticultural Professional University of Maine Cooperative Extension Penobscot County.

Do you appreciate the work we are doing?

Consider making a contribution to the Maine Master Gardener Development Fund. Your dollars will support and expand Master Gardener Volunteer community outreach across Maine.

Your feedback is important to us!

We appreciate your feedback and ideas for future Maine Home Garden News topics. We look forward to sharing new information and inspiration in future issues.

Subscribe to Maine Home Garden News

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications, click on the Subscribe button below.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

For more information or questions, contact Kate Garland at katherine.garland@maine.edu or 1.800.287.1485 (in Maine).

Visit our Archives to see past issues.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around Maine. The following staff and volunteer team take great care editing content, designing the web and email platforms, maintaining email lists, and getting hard copies mailed to those who don’t have access to the internet: Abby Zelz*, Annika Schmidt*, Barbara Harrity*, Cindy Eves-Thomas, Kate Garland, Mary Michaud, Michelle Snowden, Naomi Jacobs*, Phoebe Call*, and Wendy Roberston.

*Master Gardener Volunteers

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2023

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

In complying with the letter and spirit of applicable laws and pursuing its own goals of diversity, the University of Maine System does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender, gender identity or expression, ethnicity, national origin, citizenship status, familial status, ancestry, age, disability physical or mental, genetic information, or veterans or military status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The University provides reasonable accommodations to qualified individuals with disabilities upon request. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Director of Equal Opportunity, 101 Boudreau Hall, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5754, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).