Bulletin #2169, Pruning Woody Landscape Plants

Prepared by Lois Berg Stack, Extension ornamental horticulture specialist, University of Maine Cooperative Extension

Reviewed and updated by Manjot Kaur Sidhu, Assistant Extension Professor of Horticulture and Ornamental Horticulture Specialist, University of Maine Cooperative Extension

For information about UMaine Extension programs and resources, visit extension.umaine.edu.

Find more of our publications and books at extension.umaine.edu/publications/.

Table of Contents:

- Principles of Pruning

- Reasons for Pruning

- Pruning Techniques

- VIDEO: Pruning Ornamental Trees (YouTube)

- VIDEO: How to Prune a Lilac Bush (YouTube)

- How to Prune Various Plants

- VIDEO: Pruning Apple Trees (YouTube)

- VIDEO: How to Prune a Crabapple Tree (YouTube)

- VIDEO: How to Prune a Forsythia (YouTube)

- The Pruning Calendar

Pruning is the selective removal of parts of a plant, to improve the plant’s performance. Pruning controls the size and shape of plants and maintains plant health by removing dead, diseased, and damaged branches, to enhance effective flowering and fruiting, and guide new growth. Effective pruning of any plant is based on knowledge of the plant’s natural growth habit and how the plant will respond to the removal of its various parts (branches, buds, fruits, etc.).

Principles of Pruning

- Select plants with their long-term growth potential in mind. Consider plants’ ultimate size and form. For a small space, choose a small plant. For a narrow space, choose a columnar type. For a hedge, select a uniform, well-branched species. Pruning cannot radically change a plant’s natural growth pattern. Attempting to do so will only create a high-maintenance situation.

- Prune early, when the plant is young, to direct its future growth, rather than pruning it later in an effort to “correct” old growth.

Reasons for Pruning

Proper plant selection can minimize the need for pruning, but pruning may be required in some situations. Here are five reasons for pruning, and some examples of each:

Promote plant health

- Remove dead branches from trees and shrubs as they are identified.

- Remove diseased branches as an alternative to chemical treatment.

- Remove damaged branches that are broken or injured. Two crossed branches may rub against each other and develop bark damage and infection site; removing one of the branches early can prevent this.

- Remove spindly growth to encourage vigor in the remaining branches.

- Remove inward growing branches to direct the growth away from center of the plant.

Improve safety

- Remove low branches over walkways and lawns to eliminate a safety threat to pedestrians and people operating lawn equipment.

- Remove large, weak branches that may fall in a storm to prevent damage to buildings and other property.

- Prune back branches near electric wires to prevent a serious accident.

Improve ornamental value

Improved selections of many ornamental plants are widely available, and proper selection of these improved forms can minimize pruning. However, if some plants do not perform as expected, or if you are renovating an old landscape, pruning may enhance some ornamental characteristics.

For example:

- Selectively remove branches of a young shade tree to encourage the development of a strong, balanced canopy.

- Remove flower buds during the first year after planting a flowering tree or shrub to help the plant become better established, and enhance its long-term performance.

- Renewal prune to enhance multi-stemmed shrubs that flower on young wood.

Control growth, size and shape

In a new landscape, careful plant selection can minimize the future need to prune for size control, but an overgrown landscape may benefit from cutting back some specimens.

- Prune back or shear hedges as they reach a desired size.

- Other plants may be pruned to reduce the shade they cast over a garden, improve access to fruit, facilitate pest management, or bring an overgrown plant back into scale with its surroundings.

To produce aesthetically unusual or pleasing forms

For most landscape situations, plants should be selected for their natural form, which can be encouraged through minimal early pruning. A few specimen plant forms, however, require extensive continual pruning. Pruning can be done to produce some aesthetically pleasing forms, for example:

- Bonsai, a Japanese art form, requires extensive pruning of branches and roots to produce dwarf specimens that remain in containers and are displayed indoors.

- Topiary is a pruning and training process that transforms trees and shrubs into unique three-dimensional forms.

- Espalier creates a two-dimensional plant, often trained against a wall or fence.

Rejuvinate plants

Pruning can be done to remove old, overcrowded stems and limbs to encourage the new, healthy growth of vigorous wood in older or overgrown plants that are declining in health or becoming too large. Gradual rejuvenation is the most common method of reviving old plants, which entails removing about one-third of the oldest stems over a span of three to four years.

Pruning Tools

Most home landscape pruning can be done with basic tools like shears and saws. High-quality tools are a worthwhile investment and will last a lifetime if properly cared for. Use clean, sharp and appropriate tools for pruning. Sharpen blades before using them. Clean them with a 10% household bleach solution (1 part bleach to 9 parts water), 70% alcohol, or Greenshielddisinfectant. Dry them after use and prevent rust by applying oil regularly. To choose the correct pruning tool, consider the size of the branch that needs to be pruned.

- Pruning shears/ hand pruners: These are the most common and versatile tools, best suited for cutting thinner, smaller, and/or delicate stems, up to 1/2 or 3/4 inch in diameter. These are of two types:

- Scissors-type shears have two cutting blades and the cut is made as one blade bypasses another. They make cleaner cuts and are ideal for living plants.

- Anvil-type shears have a single cutting blade that strikes an anvil of solid metal. They can crush living stems and are therefore best for cutting deadwood.

- Lopping shears: These have long handles and heavy-duty blades, which increase your reach and leverage. They are useful for cutting larger stems, typically ¾ to 1.5 inches in diameter. Loppers are particularly useful in pruning shrubs and young trees.

- Pruning saws: These have curved blades that cut as you pull them across branches. They should be used for cutting larger branches, usually more than 1.5 inches in diameter. They should be used for cutting larger branches. Saws are available with long pole handles for pruning tree limbs from the ground.

If you are inexperienced at pruning and believe that a pruning situation requires more tools than those described above, you should consult an arborist or other landscape professionals before proceeding. Also, consult a professional if the situation requires climbing a tree for access, pruning branches that overhang a building, or working near utility lines. Avoid using hedge shears, which cut many stems with a single cut and produce plants that look awkward, stiff and unnatural.

Pruning Techniques

There are three basic pruning techniques: heading back, thinning out, and flower bud removal. The one you choose depends on the desired outcome and whether or not the plant in question is capable of producing that outcome. Some plants never require pruning, while others may need one, two, or all three of these techniques at some point in their life.

1. Heading back

Heading back is cutting back a branch to just above a good bud (there is a bud just above each leaf). This technique promotes a dense, compact growth habit in the plant, while also controlling its size and height. After the end of the branch is removed, the last remaining bud or a few buds develop into branches. The outcome depends on the plant. On some plants only the last remaining bud develops, while on others several buds develop. Also, some plants have opposite buds, while others have alternate buds.

- On plants with opposite buds and leaves (you can see pairs of leaves opposite each other along the branches), heading back to a pair of buds causes the plant to look fuller because both buds develop into branches. Lilacs, maples, viburnums, and most dogwoods have opposite buds.

- On plants with alternate buds and leaves, heading back to a healthy bud simply redirects the direction of growth. Since the buds alternate up and down the stems, you can determine the direction of future growth by pruning back to a bud pointing in that direction. Hybrid roses are often headed back to a bud that points outward to encourage an open habit, which allows better air and light penetration into the middle of the plants.

Heading back should be practiced on young branches, whose buds are able to respond. As branches age and their bark thickens, their buds are less able to develop. Heading back old branches, called topping, results in unsightly stubs. Trees should never be topped. Old shrubs and hedges should be topped only as a last resort, with the understanding that some may take a few seasons to respond, and others may not be able to respond.

2. Thinning out

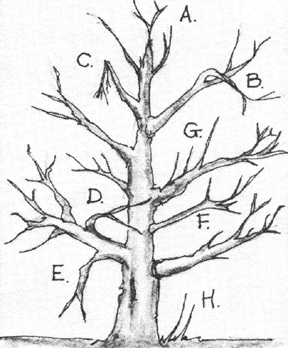

Thinning out, the complete removal of a branch back to a main stem or trunk, opens up the habit of the plant. Removing entire branches or shoots stimulates vigorous growth of remaining branches. Dead, diseased, broken, weak and crossed branches should be thinned out. A young shade tree with many branches should be thinned out so that a strong framework of fewer major limbs develops. Watersprouts, the fast-growing, weak, vertical branches that develop in apple trees, should be thinned out to encourage light penetration into tree canopies. Suckers at the base of tree trunks should also be removed. Thinning out is especially useful for plants that are too dense, for example, burning bush.

Renewal pruning

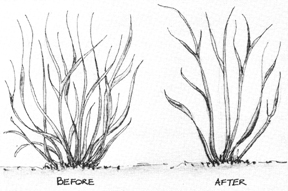

One common application of thinning is called renewal pruning, also known as rejuvenation. It is practiced on multi-stemmed shrubs, including many lilacs, viburnums, forsythias, and dogwoods. Over time, the plants’ old stems often become too tall or too crowded. Many produce fewer flowers as they grow old, and those with colored stems often lose their color. Renewal pruning corrects these problems.

The more drastic way to renewal prune is to cut the entire plant back to near ground level. Some plants, like barberry, forsythia, and potentilla, respond well to this method and quickly produce many new shoots, some of which in turn should be thinned out.

The less drastic way to renewal prune requires several years. Periodically cut the largest, oldest branches back to the ground, removing 1/4 to 1/3 of the total number of stems each time. Some aggressive shrubs require such pruning almost annually. Others may require a total renewal pruning over a period of three to four years, and then not again for several years. In order to renewal prune an old, overgrown shrub while retaining stems in the first year, and remove the remaining large stems over the next two to three years.

3. Flower bud removal

The third basic pruning technique is flower bud removal. This is often done with the thumb and forefinger rather than tools. During the first year after planting a flowering tree or shrub, the flower buds should be removed, in order to direct the plant’s energy toward maximum rooting and vegetative growth. This will improve long-term performance. On established plants, the spent flowers should be removed, or deadheaded, to encourage plant vigor. Lilacs and rhododendrons sometimes flower better if they were deadheaded the previous season. Of course, flowers should not be removed from plants like crabapple and rugose rose, which are valued for their colorful fruits.

Making the Cut

Successful pruning requires that all cuts be made in a way that allows the plant to compartmentalize, or close off, the wounds and resume healthy growth. Always use the right tool for the job, and make sure it is clean and sharp. Prune at the proper time of year (see Pruning Calendar) and follow the pruning techniques appropriate to the plant’s response potential and the desired outcome.

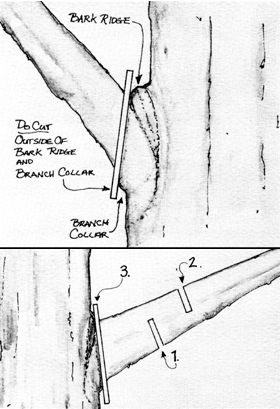

Before thinning out a branch, look closely at its structure. You will recognize the branch collar, a slightly swollen area at the base of the lower side of the branch, and the bark ridge, a V-shaped region in the top angle between the branch and the main stem to which it is attached. Both the branch collar and the bark ridge must remain intact after the branch is removed for the plant to compartmentalize the wound successfully. Never make a flush cut. Instead, locate the branch collar and the bark ridge, and angle your cut appropriately to cut just beyond them. The angle of your cut will depend on the species of plant, as the size and shape of the branch collar and bark ridge vary from species to species.

Branches large enough to be removed with a pruning saw should be removed with three cuts, because their bark may tear if they are removed in one step, causing irreparable damage. First cut upward halfway into the branch, one to two feet away from the final cut. Second, cut downward into the branch one inch out from the first cut. This will remove most of the branch. Third, make the final cut based on the location of the branch collar and bark ridge.

Tree paints and would dressings should rarely if ever, be used by a homeowner. Recent research has shown that these materials are rarely beneficial. In fact, they may sometimes prevent plants from successfully compartmentalizing wounds. Sometimes arborist use wound dressings if they are pruning at a time of year when a specific insect or disease organism is active. If in doubt, consult a professional.

How to Prune Various Plants

Deciduous trees

Shade trees and other trees that lose their leaves each fall require minimal pruning at planting time. New trees should be closely examined, and any broken branches should be removed. Most trees have a dominant central leader; if a second branch competes with the leader, it should be removed. Otherwise, all the branches should be left intact at planting time, to maximize the tree’s leaf surface for manufacturing the sugars needed to help the tree get established.

After three to four years, the tree should be well established. Suckers and watersprouts should be removed and crossing branches should be thinned out. To develop a strong branch scaffold structure, thin out some side branches; a good rule of thumb is to leave several branches evenly spaced around the tree, eight to 12 inches apart vertically. When assessing which limbs to remove, keep in mind that wide branch crotch angles (branches which extend more horizontally than vertically) are stronger than narrow branch crotch angles. Over time, a branch with a narrow-angle will weaken because the layers of wood that develop on it and the trunk will act as a wedge between them, making the branch a potential victim in a storm. Such a problem can be avoided through proper early pruning.

At five to seven years, the lower branches of the tree can be thinned out for pedestrian comfort. A few upper branches may need to be headed back to develop a graceful profile in the crown. This completes the pruning needed for deciduous trees, except for occasional removal of broken branches, watersprouts, and suckers. Examine the tree annually to assess the need for such care.

Deciduous shrubs and broadleaf evergreen shrubs

The great variability of shrubs makes them valuable in the landscape:

- Size: some shrubs are less than a foot tall while others are large enough to be used as small trees;

- Habit: shrubs may be bushy or sparse, mounded or vase-like, spreading or upright;

- Texture: coarse or fine texture may be the result of flower and leaf size and shape, peeling or smooth bark, winged stems, thorns and twigginess; and

- Season of interest: various shrubs flower from early spring to late fall and fruits may persist through winter.

Many of these traits can be embellished or suppressed through pruning. Deciduous shrubs are pruned perhaps more than any other landscape plants. The key to success is to know the shrub and its potential response to pruning, and to make pruning decisions early to direct growth, rather than correct it.

To prune for plant health, remove dead wood as it is identified. Thin out dense-growing shrubs to allow light and air penetration. Each spring, inspect shrubs for winter freeze damage. Prune winter-damaged branches back to healthy buds, but do not be too hasty; many winter-damaged buds recover and resume growth by early to midsummer.

To modify plant form and size, assess the plant’s natural growth habit. Since each cut you make redirects the plant’s growth, take care to match your pruning technique with the desired outcome. Heading back just the ends of branches causes bushiness, but only at the tips of the branches. Heading back branches further into old growth causes a more natural fullness, and keeps the plant smaller more gracefully. Renewal pruning causes a multi-stemmed shrub to be more open. Thinning out all but one major vertical stem, and removing all of that stem’s lower branches, can transform a large shrub into a small tree.

To prune for better flower display, you must know when and where your shrubs produce their flowers. Most shrubs that flower before the end of June produce their flower buds during the previous season. Examples include barberry, flowering quince, deutzia, forsythia, holly, mountain laurel, lilac, cornelian cherry dogwood, honeysuckle, mockorange, bridalwreath spirea, rhododendron, and many viburnums. Although pruning in winter does not damage these plants, doing so eliminates many of the flowers for that season. Pruning these shrubs just after they flower allows enjoyment of the flowers and allows the plants maximum time to produce new wood (along with the next year’s flower buds) before the end of the season.

Several shrubs may produce a second flowering if they are lightly pruned just after their early summer flowering. The success of this technique greatly depends on plant type, plant vigor and season length (it is less successful in northern Maine’s cool, short summers.) Some shrubs capable of this are buddleia, red-stem dogwood, cranberry and multiflora cotoneasters, summer blooming pink and lavender spireas, snowberry, coralberry, and weigela.

Most shrubs that flower after the end of June produce their flower buds early in the current season, on new wood. These include buddleia, clematis, clethra, rose of sharon, hydrangea, potentilla, and rose. These shrubs should be pruned in winter or early spring, just before the season’s growth begins.

Remember that removing flowers eliminates fruit development. If you prize your shrub’s fruits for their ornamental, edible or wildlife value, do not prune off the flowers.

Needled evergreen trees

Maine’s evergreen trees, which require minimal pruning, have narrow leaves referred to as needles. They also have a conical or pyramidal form, with a dominant central stem, or leader, and layers of branches which radiate out in whorls along the main stem. Generally, one whorl is produced per year, and the whorl branches do not compete with the central leader.

These trees, including pines, spruces, hemlocks, firs, and Douglas fir, can be pruned for denser growth in spring, as the buds, called “candles,” expand. Do not use pruning shears, which damage the needles and cause their tips to turn brown. Use your thumb and forefinger to pinch out 50 percent of each candle.

In a drastic situation, evergreen trees’ central leaders can be pruned to reduce height. Prune as little as possible. Prune back to a lateral whorl that is actively growing and well-needled. Older tissue of these trees does not have living buds.

Many pyramidal evergreens develop a more picturesque form as they mature; this is normal, and pruning does not prevent it.

Narrow-leaved evergreen shrubs

Juniper, yew, chamaecyparis, cedar (arbor vitae) and other narrow-leaved evergreen shrubs vary greatly. Shrub junipers, for example, can vary in height from two inches to six feet. Select plants carefully, and avoid replying on pruning to manipulate height and form.

Some size control can be accomplished by selectively heading back long branches. Yew and cedar (arbor vitae) can be pruned back further than juniper and chamaecyparis, whose older wood often does not have buds. Generally, it is a good idea to prune a branch no further than back to the last green side branch, unless you are thinning out the entire branch. If you start at the top of the plant and work downward, and prune branches to various lengths, the result will be a smaller shrub that shows no sign of having been pruned.

A few needled evergreens, like mugo pine, are grown as shrubs. Their size is best controlled by pinching our 50 percent of each candle (see description under evergreen trees).

Hedges

There are two basic types of pruning for hedges: formal hedges that are sheared for a controlled and defined shape, and informal or natural hedges that are pruned for a shape determined by the natural growth habit of the plant. Many upright-growing, well-branched shrubs, both deciduous and evergreen, can be grown as hedges. Evergreen trees such as pine, spruce and hemlock can also be used where there is room for a larger hedge.

Regardless of the type of pruning for a hedge, there are a few important considerations:

- Begin training a hedge early by heading back top and side branches in the first or second year after planting, to promote branch development and full, low growth from the beginning. It is often hard to obtain a dense hedge if it has not been pruned in the early years of growth.

- Always prune the top of a hedge narrower than the bottom to allow light penetration and encourage branching at the base of the plants. Periodic heading back maintains the hedge’s form and size.

Pruning versus shearing: Pruning refers to selectively cut individual branches while shearing is cutting all the branches indiscriminately. The latter is used in specialized situations like maintaining formal hedges or topiaries.

When and how? The frequency, timing, and technique of hedge pruning depend on the plants used and the effect desired. A formal hedge may require heading back of young branches one to two times each year. Shears can be used, but the process of shearing leaves unsightly twigs at the periphery of the hedge and looks less natural. Avoid the temptation to shear a hedge closely every year. Close shearing year after year promotes a dense twiggy growth at the periphery of the hedge that sunlight cannot penetrate, and leaves and buds in the center of the hedge die. On an evergreen hedge, if the peripheral growth is killed in a harsh winter, regrowth will not be possible if the shaded buds have died. On a sheared deciduous hedge, the winter appearance is that of a bad haircut, because shearing promotes unnatural layers of twiggy growth, which can be an eyesore after the leaves have fallen.

Where an informal and more natural hedge is desired, size control is best accomplished through careful plant selection. Informal hedges are further kept within bounds by heading back branches with hand shears once every year or two. Pruning with hand shears allows you to selectively leave some branches longer than others, for a more natural appearance than shearing. The greater amount of growth allowed to remain on an informal hedge also promotes a more natural appearance. Hedges of multi-stemmed plants can be kept in bounds by renewal pruning as needed.

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 1998, 2025

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

In complying with the letter and spirit of applicable laws and pursuing its own goals of diversity, the University of Maine System does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender, gender identity or expression, ethnicity, national origin, citizenship status, familial status, ancestry, age, disability physical or mental, genetic information, or veterans or military status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The University provides reasonable accommodations to qualified individuals with disabilities upon request. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Director of Equal Opportunity and Title IX Services, 5713 Chadbourne Hall, Room 412, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5713, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).