Bulletin #2272, Forage Facts: Selecting Forage Crops for Your Farm

Developed by Timothy S. Griffin, Extension Sustainable Agriculture Specialist

Reviewed and updated by Donna Coffin, Extension Professor, University of Maine Cooperative Extension

For information about UMaine Extension programs and resources, visit extension.umaine.edu.

Find more of our publications and books at extension.umaine.edu/publications/.

Table of Contents:

- Climate and Weather

- Table 1. Drainage capability of Maine soils

- VIDEO: How To Frost Seed (YouTube)

- Soil Drainage

- Table 2. Drainage tolerance of perennial forage crops

- Soil Acidity (pH)

- Table 3. Soil pH ranges for forage crops grown in Maine

- Harvest Management

- Carbohydrate Reserves

- Remaining Leaf Area After Harvest

- Tillering

- Table 4. Soil pH ranges for forage crops grown in Maine

- VIDEO: How To Test Forage Quality (YouTube)

- Special Consideration for Grazing Systems

- Table 5: How forages respond to harvest management

- Summary

The forage crops on your farm are a long-term investment of your time and money. Pastures and hayfields, unlike corn, potatoes or vegetables, are planted with the intention of harvesting them for three to five years or more.

If you are planning to make a new forage seeding, plan ahead. Determine which forages are best suited to your needs. Don’t make this decision as you hook the planter up to the tractor. Put some thought into your choice. You have to live with it!

In this fact sheet, we discuss some of the most important factors that influence your choice of forage crops. We also provide you with some examples. In general, these factors are listed in the order that you should consider them.

First, make a list of all types of forage you might plant. As you read through the fact sheet, the list of forage crops that could be used on a specific field will become shorter. When you reach the end, the forage crop(s) left on your list will be the ones best suited to your operation.

Climate and Weather

Obviously, you can’t control the weather. Weather patterns throughout the year, especially during the winter, strongly affect which forages work in Maine and which do not.

For grasses like timothy and Kentucky bluegrass, the weather is usually not a problem; they do well in Maine. Other forages, like alfalfa and various clovers, can suffer severe or complete winterkill if there is little snow cover. However, there are varieties available that can survive most Maine winters if other factors (like soil drainage) are favorable. There are also differences in winter hardiness requirements from southern Maine to northern Maine.

Crops in Maine must have enough winter hardiness to survive the severe winters. Depending on your location in the state, choose forage crops and forage varieties with enough winter hardiness to survive.

Winterhardy legumes include birdsfoot trefoil, some varieties of alfalfa and various clovers. Legumes without enough winter hardiness are much more likely to experience winterkill by disease, frost-heaving or suffocation under ice. Timothy is a very winter-hardy grasses. Orchardgrass and smooth bromegrass will experience some winterkill, especially on soils that are not well drained (see Table 1). Other grasses, like perennial ryegrass, do not have enough winter hardiness to consistently survive Maine winters, although varieties being developed may be adapted to northern New England.

Soil Drainage

The wetness or dryness of your soils also strongly affects forage crops selection. Soil drainage can affect plants in several ways:

- If soils are waterlogged or saturated for long periods of time, oxygen in the soil becomes scarce, and plant growth is slowed or stopped.

- Plant diseases are more likely to develop in wetter soils.

- If surface drainage is poor, ice sheets can form during the winter. These ice sheets can completely kill stands of alfalfa and other legumes and some grasses (like orchardgrass).

- Shallow-rooted plants may not survive drought periods on excessively drained soils.

Unlike the weather, we have some (but not much) control over soil drainage. In some situations, tile drainage of poorly drained soils may be an option. More often, soil drainage is “controlled” by selecting fields that meet the requirements for a particular crop. For example, you obviously don’t plant alfalfa in a field that is waterlogged every spring.

All of the agriculture soils in Maine belong to a soil series. Each soil series is classified according to its drainage capability, from excessively drained to very poorly drained. Table 1 shows some examples of the drainage capability of Maine soils. Your local Extension or Soil Conservation Service office can help you identify the soils on your farm.

When you know your soil types, you can narrow down the list of forages that will work well on each field. In Table 2 below, you’ll find some guidelines on the range of soil drainage tolerated by common forage crops. Find out what soil types you have on your farm and what the drainage capability of each soil is. Then choose your forage crop accordingly.

Find out what soil types you have on your farm and what the drainage capability of each soil is. Choose your forage crop accordingly.

Soil Acidity (pH)

Soil acidity is measured in “pH units.” A pH below 7.0 means the soil is acid or “sour”. A pH above 7.0 means the soil is basic. Soils in Maine are naturally acid. Most of our soils have a pH between 4 and 6. Soil acidity is desirable if you are growing blueberries or potatoes. However, along with nitrogen deficiency, low pH is a major factor limiting the productivity of Maine pastures and hayfields.

Acid soils cause several problems. For forage crops, for instance, plant growth is slower. This may be due to a direct effect on the plant, although pH would have to be 4.5 or lower. More likely, slow plant growth is due to changes in nutrient availability as pH falls.

Many of the major plant nutrients in the soil (nitrogen, calcium, magnesium, phosphorous, potassium, sulfur, molybdenum and boron) become less available as pH level drops. The result is that it is more difficult for plants to take up the nutrients they need to grow. At soil pH below 5.0, the availability of aluminum, iron and mangenese increases. In fact, their level in the soil may reach toxic levels. The change in nutrient availability affects both grasses and legumes.

Legumes can be affected by low soil pH in another way. The nitrogen-fixing bacteria in the roots are more sensitive to acid conditions than the plant itself. So as pH goes down, the plant may survive, but nitrogen fixation stops. In pastures where you depend on legume nitrogen fixation for grasses, total yield is lower. If you have trouble maintaining legumes in pastures or hayfields, take a soil test to determine soil pH.

Soil pH can be adjusted by applying lime or other products, like wood ash or lime-stabilized sewage sludge. Be aware that soil pH is a factor in selecting forage crops only if you do not intend to change it. Don’t adjust soil pH only at planting time. Soil pH will drop naturally over a period of years, especially if nitrogen fertilizer is applied to grass pastures or hayfields. Soil testing every year will tell you when to apply lime again to adjust pH for a specific forage crop.

There are distinct differences between forage crops in their ability to grow at different soil pH levels. In general, grasses are less sensitive to acid conditions than legumes are. Table 3 shows some pH ranges for forage crops commonly grown in Maine. The forage crops listed in Table 3 will grow if soil pH is outside the range shown. However, you can expect lower yields and a shorter stand life, especially if pH is below the range shown. Optimum yields are possible if pH is maintained in the top one-half of these ranges.

For a given climate and soil type, your choice of which forage crop to use depends on how you are going to use it.

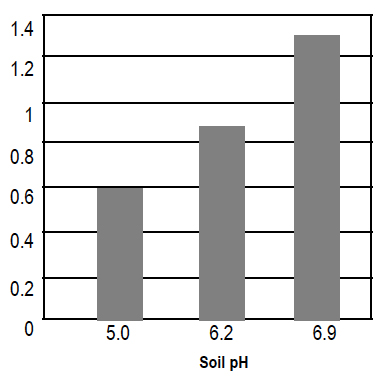

As an example, Figure 1 shows the effect of soil pH on alfalfa yield in Wisconsin (from Undersander, 1989). These yields are for only the first alfalfa harvest after seeding. However, the difference in yield is apparent; twice as much alfalfa was harvested at pH 6.2 compared to pH 5.0.

Think about that yield difference for a moment. Remember that you want your alfalfa stand to last three to five years. The difference in yield over time can be substantial. It pays to pay attention to soil pH.

Harvest Management

After considering climate, soil drainage, and soil pH, you’ve probably narrowed down the forage crops that fit in a particular field on your farm. Maybe you also noticed that each of these factors is more under your control than the one before it. We now will look at harvest management for hay and silage crops and for pastures. Harvest management is a factor that is almost completely under your control (except if the harvest date is changed by weather).

For a given climate and soil type, your choice of which forage crop to use depends on how you are going to use it.

These are the questions to ask:

- How often will the forage be harvested?

- What is the time period between harvests?

These questions are important because different forage crops react differently to harvest management. The number of times that a forage crop can be harvested and the time between harvest depends on several things, including

- the level of carbohydrate reserves;

- the amount of leaf area remaining after harvest; and

- the number of new tillers or stems that have begun to grow.

Carbohydrate Reserves

Plants regrow at different rates after being harvested. This directly influences how soon they can be harvested again.

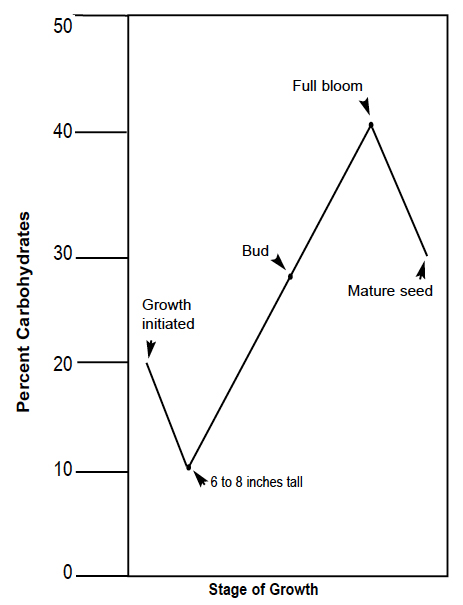

Energy in the form of carbohydrates or sugars is stored in crowns, roots or rhizomes. After the plant is harvested, this energy is used to support new growth, and the level of carbohydrates in the roots goes down. It reaches the lowest point when the plant is six to eight inches tall. The highest point is at full flowering.

Harvesting or grazing when plants are less then eight inches tall will weaken some plants and make regrowth occur more slowly. The carbohydrate reserve cycle, which is shown above in Figure 2 for alfalfa, takes place in all perennial plants. Plants differ in how quickly energy levels are built up again. Alfalfa builds up carbohydrate levels fairly quickly. Carbohydrate levels in birdsfoot trefoil may remain low all summer long. The plant should not be cut until carbohydrate levels reach adequate levels; this usually occurs at the early flowering stage.

Timothy and smooth bromegrass regrow slowly after harvest, although some varieties regrow faster than others. Timothy takes longer than bromegrass to replenish carbohydrate reserves after harvest. Birdsfoot trefoil also regrows slowly after harvest. These three plants, timothy, birdsfoot trefoil and smooth bromegrass, generally can only be harvested twice a year in Maine. Plants that regrow rapidly include alfalfa, and orchardgrass. They may be harvested three or more times per year. The number of harvests may be even more strongly affected by other factors, like soil fertility.

Carbohydrate reserves are the plant’s only source of energy for winter survival and new spring growth. Thus, the level of carbohydrate reserves in the fall is critical if you want to maintain forage stands long-term. Generally, this means not harvesting the plant for about six weeks prior to the first killing frost. Remember that other factors, like plant species, variety and soil fertility, also have a large impact on the plant’s ability to overwinter.

Remaining Leaf Area After Harvest

When plants are harvested, either by machine or by an animal, there are usually some leaves that are not completely removed. The amount of leaf area that remains after harvest depends on the cutting height or the grazing pressure. Photo-synthesis by these leaves supplies energy for regrowth, which can make a drop in carbohydrate reserves less severe; regrowth is more rapid.

Some plants cannot tolerate severe defoliation because they rely on the remaining leaf area for energy. This is especially true for birdsfoot trefoil. Trefoil depends on older, lower leaves to produce energy for regrowth, rather than carbohydrate reserves. Trefoil should not be grazed closely ore cut shorter than four inches.

Kentucky bluegrass and white clover, which are common in continuously grazed pastures, also rely on remaining leaf area for energy. However, both plants are very low growing, so it is difficult to graze them low enough to remove all leaf area. This is the main reason why these plants dominate continuously grazed pastures.

Tillering

Another factor affecting the regrowth rate is tillering. If plants are harvested later than the vegetative stage (when only leaf material is removed), new growth must come from new tillers or stems. Some plants, like orchardgrass, produce new tillers continuously throughout the season. This results in very rapid regrowth when orchardgrass is harvested. It also means that carbohydrate reserves of orchardgrass are fairly low, so orchardgrass can be cut or grazed often, but there must be adequate leaf area left after harvest to support new growth. Other plants, like timothy, do not begin to form new tillers until the seedhead stage or later. When timothy is harvested, regrowth is slower because new tillers must develop and then grow. As a result, timothy can be cut close, but not often. Table 4 shows when some common forage plants produce new growth from the crown.

Special Consideration for Grazing Systems

The biggest difference between machine harvest and grazing of forage crops is that machine harvesting removes all growth at one time. Grazing, on the other hand, removes selected plants over a period of time.

For pastures, both the grazing period and the rest period are important for managing plant growth. The grazing period should not exceed the time it takes for the plant to begin regrowth. If the grazing period is longer, individual plants are harvested again when they are still very immature. This means that they are harvested when carbohydrate reserves are low; plants may weaken and regrowth may be slow. The rest period, then, should be long enough for the plants to develop sufficient leaf area for grazing and to replenish carbohydrate reserves. The length of both periods depends on the rate of plant growth as it changes throughout the growing season. Table 5 shows the suitability of forages for different uses.

Summary

Climate and winter hardiness. Soil Drainage. Soil pH. Harvest management. All of these factors influence your choice of forage crops. To make a decision, it is important that you have a realistic ideal of what your forage crops will be used for and how they will be managed. Using reliable information, you can then make an informed decision as to which forage will best fit your needs.

For more information about forage crops, contact your local UMaine Extension County Office.

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2004, 2022

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

In complying with the letter and spirit of applicable laws and pursuing its own goals of diversity, the University of Maine System does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender, gender identity or expression, ethnicity, national origin, citizenship status, familial status, ancestry, age, disability physical or mental, genetic information, or veterans or military status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The University provides reasonable accommodations to qualified individuals with disabilities upon request. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Director of Institutional Equity and Title IX Services, 5713 Chadbourne Hall, Room 412, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5713, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).