Bulletin #2424, Insecticide Resistance in Colorado Potato Beetles

Developed by Associate Professor Andrei Alyokhin, Extension Professor James Dwyer, and Assistant Extension Professor Andrew Plant.

For information about UMaine Extension programs and resources, visit extension.umaine.edu.

Find more of our publications and books at extension.umaine.edu/publications/.

Table of Contents:

- Colorado Potato Beetle

- The Phenomenon of Insecticide Resistance

- Preventing Insecticide Resistance

- Table 1. Insecticides Registered for Colorado Potato Beetle Control

- Additional Information

- Full Descriptions for Figures

The Colorado Potato Beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata, is the most significant insect pest of the solanaceous family of plants, which includes potatoes, tomatoes, and eggplant. Both adults and larvae feed on plant foliage. In the absence of control measures, Colorado potato beetle damage can result in complete defoliation of potato fields.

Colorado Potato Beetle

Life Cycle

Colorado potato beetles overwinter in the soil as adults, often aggregating in woody areas adjacent to the fields in which they have spent the previous summer. Starting in late May, the overwintered beetles dig themselves out of the soil and mate. Then they colonize potato fields, feed for several days, and start laying eggs. If fields have been rotated, these beetles are able to fly up to several miles to find new host habitat. Overwintered adults live for one to two months after colonizing host plants in the spring.

A single Colorado potato beetle female is capable of producing roughly 600 eggs. Eggs laid by the overwintered beetles begin to hatch within one week. Newly emerged larvae disperse over short distances and almost immediately start feeding on potato foliage. The larvae spend most of their time on plants. They undergo three molts over the course of 10 to 20 days and then burrow into the soil to pupate. The pupal stage lasts for 10 to 15 days. Then the first summer generation of adults digs out of the soil and climbs back onto potato plants to feed. It takes them about 7 to 9 days to develop reproductive systems and flight muscles. After development has been completed, the beetles mate and start laying eggs.

The reproduction continues until diapause (dormancy) is induced by decreasing day length in early to mid-August. Then the beetles either walk to the overwintering sites or burrow into the soil directly in the field. In Maine, usually, a single generation is completed during the growing season, although two generations may be possible in southern parts of the state during especially warm years. Later generations are usually less of a concern for potato growers because of their smaller size, as well as the fact that mature plants can better withstand defoliation without yield reduction.

Figure 1. Colorado potato beetle life stages.

The Phenomenon of Insecticide Resistance

Pesticide resistance in arthropods costs farmers millions, if not billions, of dollars each year. Currently, more than 500 different species of arthropods are resistant to a wide variety of chemicals.

Insects may decrease their susceptibility to toxins in a variety of ways. In some cases, they become capable of digesting insecticides before their vital organs and tissues are affected. In other cases, their bodies change on the molecular level so that toxins no longer affect them. In still other cases, resistant individuals quickly excrete the poisons before the damage is done. Also, some resistant insects may become less exposed to insecticides, either because they become capable of detecting and avoiding toxins, or because toxin penetration through the body wall is reduced.

Insecticide resistance is a matter of the frequency of resistant individuals in the population. The simple presence of resistant genes does not mean that a particular insecticide is doomed. As long as resistant individuals are few and far between, they are not capable of doing enough damage to decrease the yield. Thus, effective control is still being achieved.

Development of insecticide resistance in insect populations is a typical evolutionary process driven by survival of the fittest individuals. Initially, resistant insects result from random mutations caused by internal factors, such as various molecules bumping against DNA in their chromosomes, or external factors, such as solar radiation. Under normal conditions, survivorship and reproductive success of resistant mutants is usually lower than that of susceptible insects of the same species. Therefore, relatively few resistant mutants persist in a population that is not exposed to a particular insecticide to which they have developed resistance.

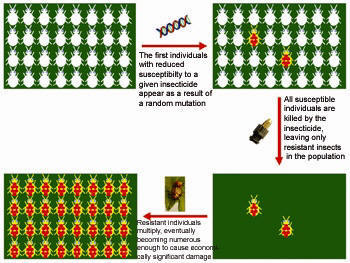

Full description for Figure 2, below.

Full description for Figure 3, below.

The situation changes dramatically when such an insecticide is applied. The chemical kills off susceptible genotypes, while resistant mutants survive and thrive in the absence of competition. Pretty soon, their numbers increase to the densities sufficient to cause significant economic damage.

Most commonly, insects become resistant to a single chemical to which they were exposed. However, in some cases, resistance to one pesticide results in resistance to multiple pesticides. Usually—but not always—these pesticides have similar chemistry and modes of action (ways they kill their target pests). This phenomenon is known as cross-resistance. In other cases, simultaneous and/or successive selection by several different pesticides may result in resistance to all of them. This phenomenon is known as multiple resistance.

Insecticide resistance in the Colorado potato beetle

The Colorado potato beetle has a remarkable ability to develop resistance to a wide range of pesticides. Plants in the family Solanaceae, which are natural food sources for this insect, have high concentrations of rather toxic glycoalkaloids in their foliage. These toxins protect them from a wide range of herbivores. However, Colorado potato beetles have evolved an ability to overcome the toxic defenses of its hosts. Apparently, this ability also helps them to adapt to a wide range of human-made poisons. Also, high beetle fecundity increases the probability that one of the numerous offspring mutates, as well as ensures that the resistant population builds up rapidly once such a mutation has occurred.

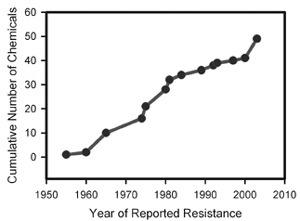

The first instance of Colorado potato beetle resistance to synthetic organic pesticides was noted for DDT in 1952. Resistance to dieldrin was reported in 1958, followed by resistance to other chlorinated hydrocarbons. In subsequent years, the beetle has developed resistance to numerous organophosphates and carbamates. In some cases, a new insecticide failed after one year — or even during the first year — of use.

Presently, resistance has been reported to nearly every chemical that has ever been used to control Colorado potato beetle. Obviously, not every single population is resistant to all insecticides. However, both cross-resistance and multiple resistance are rather common. The major problem area is the northeastern United States; however, resistance has also been detected in other areas of the U.S., as well as in Canada, Europe, and Asia.

Physiology and genetics of resistant beetles

Although many details still need to be figured out, a significant amount of information on insecticide resistance in the Colorado potato beetle is already available.

First, we know that in the absence of insecticides, the fitness of insecticide-resistant individuals is usually low compared to insecticide-susceptible individuals. They have lower reproductive success, higher mortality, and are incapable of successful competition with their susceptible brethren.

Secondly, insecticide-resistant versions of genes are usually incompletely dominant, meaning that the level of resistance in hybrid crosses between resistant and susceptible beetles are somewhere in between that of their parents.

Third, when such semi-resistant hybrids mate with each other, some of their offspring will be highly resistant.

Preventing Insecticide Resistance

Preventing resistance is as essential a part of good insecticide stewardship as minimizing drift or wearing personal protective equipment. Similar to most other problems, resistance is more easily avoided than mitigated. Don’t wait until insecticide failure becomes noticeable in the field, as you may find yourself with few control options. A better strategy is to incorporate these preventive practices into your management system:

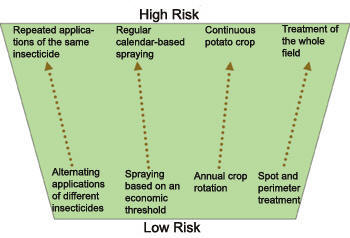

- Identify fields where Colorado potato beetles are at high risk of developing resistance. In theory, any field that has been treated with insecticides is at risk. However, in some fields, the risk is higher than on the others. Generally speaking, the more extensively a given chemical—or class of related chemicals—is used, the higher the probability becomes that it will fail due to resistance development (Figure 4). Conversely, integrating various chemical and non-chemical techniques will keep beetle populations under damaging levels for greater periods of time.

- Rotate among different insecticide mode-of-action groups. Relying on a single insecticide as a sole method of keeping the beetle populations in check will eventually result in failure. Relying on a single class of chemically related insecticides will have the same effect: similar chemicals are likely to poison their target insects in a similar way. If an insect becomes capable of overcoming one of them, it is fairly likely that it will also overcome another one that has a similar chemical structure and mode of action. This phenomenon is known as cross-resistance. The Insecticide Resistance Action Committee, a specialist technical group supported by the agrochemical industry, has arranged all insecticides in groups based on the similarities in their chemical structures and modes of action. Insecticides belonging to different mode-of-action groups (Table 1) should be rotated throughout the growing season.

- Use the full label rate of insecticides. Otherwise, you might not kill the hybrid crosses between resistant and susceptible beetles (“Physiology and genetics of resistant beetles”).

- Do not rely on insecticides alone. Every grower should practice crop rotation, which has been repeatedly shown to suppress Colorado potato beetle populations. Rotated fields should be located as far from the previous year’s crop as possible so that the beetles have difficulty finding them. This allows growers to reduce the number of insecticide applications necessary to control the beetles, thus reducing selection pressure towards resistance development. For example, an average of 4.78 insecticide applications was required to control Colorado potato beetles on non-rotated commercial potato fields during the 2005 growing season in southern Maine, compared to only 2.73 applications on rotated fields.

-

Figure 4. Risk of insecticide resistance depends on management practices. (Schematic by Andrei Alyokhin)

Figure 4. Risk of insecticide resistance depends on management practices. (Schematic by Andrei Alyokhin) Full description of Figure 4, below.

Use economic thresholds when making decisions about spraying. Not only does chasing every single beetle with a sprayer result in wasted time and money; it also contributes to rapid resistance development. Trying to kill all the beetles with insecticides usually results in killing all susceptible beetles. Only resistant beetles survive—which is why they are called resistant in the first place. When resistant beetles mate with each other, all their progeny are resistant. When resistant beetles mate with susceptible beetles, their progeny are less resistant, and usually can be killed by the full label rate of insecticide.

- Leave untreated refuges in which susceptible beetles can survive. If you apply insecticide in-furrow or as a seed treatment to the whole field, you lose the advantage of treating according to economic thresholds. In addition, you still need to supply susceptible mates for resistant beetles. Unless you intend to run a dating service for lonely beetles, leaving a few untreated rows at planting is your best solution. If necessary, those can be treated later with foliar sprays.

Preventing resistance development requires additional effort on the grower’s part. However, the era of cheap and readily obtainable insecticides is coming to an end. Therefore, few control options may be on hand if currently available chemicals fail as a result of resistance. Good stewardship of existing products is essential for ensuring long-term success in chemical pest control.

Additional Information

Please visit this publication’s companion website, “Insecticide Resistance in the Colorado Potato Beetle,” at PotatoBeetle.org’s Insecticide Resistance page. You will find detailed information on Colorado potato beetle (CPB) life history, resistance development, the timeline of CPB resistance, management principles, and links to other resources, including a CPB bibliography.

This publication is based upon work supported in part by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Pesticide Environmental Stewardship Program (PESP) Region 1 Assistance Award No: PE-97145501.

Visit the Colorado Potato Beetle Biology and Management/potatobeetle.org website.

- CPB biology and management

- History

- Insecticide resistance

- Bibliography

- Resources

Full Descriptions for Figures

Figure 2: Schematic depicts four green rectangles arranged in a square, linked by clockwise arrows. Beginning from the top left, the first rectangle is filled with beetle silhouettes (4 rows of 8 each for a total of 32), all of them white. Over the arrow joining the first rectangle with the second is a stylized image of the DNA double helix. Under the arrow is this caption: “The first individuals with reduced susceptibility to a given insecticide appear as a result of a random mutation.” The second rectangle shows the same 32 beetle silhouettes, except that two of them are colored red and yellow. The arrow down from the second to the third rectangle has a spray nozzle on one side of it and this caption on the other: “All susceptible individuals are killed by the insecticide, leaving only resistant insects in the population.” The third rectangle contains only the two red and yellow beetles; no white beetles. The arrow pointing left from the third rectangle to the fourth has a photo of two beetles mating above it, and this caption below it: “Resistant individuals multiply, eventually becoming numerous enough to cause economically significant damage.” The fourth rectangle shows 32 beetles, but they are all colored red and yellow.

Figure 3: The rectangular chart contains data points connected by a line that trends upward at about a 45-degree angle The X-axis values at the bottom of the chart are labeled “Year of Reported Resistance,” and run from 1950 on the left to 2010 on the right, in ten-year increments. The Y-axis values up the left side are labeled “Cumulative Number of Chemicals” and run from 0 a the bottom to 60 at the top, in increments of 10. The data points are as follows:

| Year | Cumulative Number of Cases |

|---|---|

| 1955 | 1 |

| 1960 | 2 |

| 1965 | 10 |

| 1974 | 16 |

| 1975 | 21 |

| 1980 | 28 |

| 1981 | 32 |

| 1984 | 34 |

| 1989 | 36 |

| 1992 | 38 |

| 1993 | 39 |

| 1997 | 40 |

| 2000 | 41 |

| 2003 | 49 |

Figure 4. The figure depicts trapezoid with top and bottom lines parallel, the top line being longer and thus the top of the trapezoid being wider. The label below trapezoid reads “Low Risk” and label above trapezoid reads “High Risk.” Four phrases appear along the inside bottom of the trapezoid, above “Low Risk.” Each is topped by an arrow pointing up at a slight outward angle to a corresponding phrase at the inside top of the trapezoid, under “High Risk.” The following table conveys the pairing of the phrases:

| Low Risk | High Risk |

|---|---|

| Alternating applications of different insecticides | Repeated applications of the same insecticide |

| Spraying based on an economic threshold | Regular calendar-based spraying |

| Annual crop rotation | Continuous potato crop |

| Spot and perimeter treatment | Treatment of the whole field |

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2008

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

In complying with the letter and spirit of applicable laws and pursuing its own goals of diversity, the University of Maine System does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender, gender identity or expression, ethnicity, national origin, citizenship status, familial status, ancestry, age, disability physical or mental, genetic information, or veterans or military status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The University provides reasonable accommodations to qualified individuals with disabilities upon request. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Director of Institutional Equity and Title IX Services, 5713 Chadbourne Hall, Room 412, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5713, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).