Bulletin #4298, Best Practices for Washing Produce and Use of Sanitizers on Commercial Farms

By Chris Howard, Produce Safety Professional, Jason Bolton, Associate Extension Professor and Food Science Specialist, and Robson Machado, Assistant Extension Professor and Food Science Specialist University of Maine Cooperative Extension.

For information about UMaine Extension programs and resources, visit extension.umaine.edu.

Find more of our publications and books at extension.umaine.edu/publications/.

Table of Contents:

Introduction

What does it mean to “wash” your produce?

What type of produce can be washed?

Why should produce growers consider washing their produce?

What are the types of wash systems?

What is the cleaning process for food contact surfaces?

How do growers choose a sanitizer and use it correctly?

What are the common types of sanitizers and how should growers prepare them?

What to monitor as you use sanitizers in your wash water

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Resources

Introduction

As we all know, many fruits and vegetables grow outdoors on, or in, the soil. Most people know this fact and will not expect that a carrot is as clean as a loaf of bread. Some soil or debris on fresh produce is usually acceptable, especially when selling in direct-to-consumer markets. Regardless, it is not a surprise that some consumers’ expectations have evolved over time to buying produce that is clean and flawless. Also, there are extra benefits to having “clean” produce to bring to your markets, such as fruits and vegetables holding up longer in storage. This factsheet clarifies best practices for washing produce for the benefit of you and your consumers.

What does it mean to “wash” your produce?

To “wash” your produce means you use water to remove the soil and debris off the produce as well as reduce the presence of any bad microbes that could cause foodborne diseases. It does not mean using soaps or detergents on the produce. “Washing” produce can be done in many ways including dunking the produce (such as in a sink), spraying off the produce (such as on a table with a screen top), using a vegetable wash table with a conveyor belt and spraying water, etc. Some farms will choose to use sanitizers in the wash water to prevent cross-contamination from one produce to another (we will discuss best practices below.) Some produce tolerate having soil and debris removed and will hold up well in storage and look great. But you need to think carefully about which of your products should be washed and which shouldn’t. If you wash produce that has fragile skin (such as a strawberry) it will not have a very long shelf-life AND you run the risk of introducing cross-contamination through the water unnecessarily.

What type of produce can be washed?

Produce that can be washed includes any fruits and vegetables with skin tough enough to withstand being wet (sprayed or dunked) without starting to break down. This includes (but is not limited to): apples, winter squash, peppers, melons, carrots, beets, lettuce, kale, cauliflower, broccoli, cabbage, onions, zucchini, cucumbers, swiss chard, rutabaga, turnips, eggplant, and potatoes.

Not all produce should be washed. Produce that isn’t usually washed includes (but is not limited to): sweet corn, blueberries, strawberries, raspberries, tomatillos, tomatoes, green beans, cherries, and peas.

Why should produce growers consider washing their produce?

- To remove soils and debris that are on the produce after harvest. Chances are your market’s demand is for produce that is free of garden soils and other debris. Usually, you want to make the produce look pristine for the markets you attend. We all know attractive displays sell better!

- To reduce the number of harmful microbes that make people sick. Produce grows close to the ground and it may be contaminated by:

- raw manure

- non-finished compost

- feces from domestic or wild animals

- contaminated irrigation water

- cross-contamination during the harvest process by dirty hands, dirty knives, or dirty bins

NOTE: Produce washing should not be considered a treatment step. It reduces or removes soil and other debris, but it does not necessarily make the produce safe. When a sanitizer is added to the water, however, it can help prevent the spread of contamination to other produce items and surfaces.

- Because produce that is free of soils and debris can have a longer shelf-life.

What are the types of wash systems?

- Single-pass wash system: Water is sprayed on produce to wash off soil and other debris. The water used in this system drains completely and is not recirculated or reused in any way. There is a low risk of cross-contamination because only clean water is used, then drained after contacting produce. No sanitizer is needed in this system. Examples of a single pass wash system include spraying vegetables on a mesh-topped table; a single-pass vegetable wash table with water drains and no recirculating water.

- Recirculating wash system: Water is sprayed or poured onto produce, then collected after contacting produce and pumped back up to wash more produce. This practice has a higher risk of cross-contamination because you’re reusing the water. The best practice is to use a sanitizer in the recirculating wash water. An example is a rinse conveyor system.

- Immersion wash system: Water is placed in a tank or sink and vegetables or fruit (commonly apples in Maine) are dumped into the tank. The tank may have some form of agitation and/or a conveyor for the apples or vegetables to move up and out of the tank once they have been in the tank for a set amount of time. There is a higher risk of cross-contamination here because you’re reusing the water. The best practice is to use a sanitizer in this system’s wash water.

- Triple wash system: Water is placed in three sinks, where produce (often greens) gets dunked in each sink. Greens get submerged in sink 1 for a set amount of time, typically a few minutes (often agitated by hand) and then they are moved to sink 2 to soak for a set amount of time, then they are moved to sink 3 to soak for a set amount of time. Ideally, each time they are moved they will shed dirt and contaminants. The best practice is to have a sanitizer at least in the water of sink 3 to prevent cross-contamination since all the leaves are submerged in the same water and there is bound to still be some contaminants left in the water, even on the third dunking. You can use sanitizer in all sinks if you want. For greens, you can use a salad spinner to get rid of the excess water which will help dry the surfaces of the greens quicker which helps stop the spread of contaminants and helps give the product a longer shelf-life.

After washing produce, the best practice is to clean and sanitize the tank/sink/table/bin you used. This can be as frequent as determined necessary in your farm produce safety plan (after every batch of produce, or after each day of harvest, etc.) The FSMA Produce Safety Rule states that any food contact surfaces must be visibly clean before use. When a surface becomes visibly contaminated (e.g., with feces from the field or blood from an injured worker) it must be cleaned AND sanitized. If it becomes visibly dirty (with soils or debris) it must be cleaned. You don’t have to clean and sanitize after every use…you be the judge.

**REMEMBER – a food contact surface must be cleaned before it can be sanitized.

What is the cleaning process for food contact surfaces?

Cleaning means using a detergent and a brush to scrub the surface to remove soils and possible slime buildups (biofilms). Scrubbing is recommended to remove and prevent biofilms from developing. Cleaning must always be followed by a clean water rinse, if wet cleaning, before applying sanitizer because if detergent is left on the surface, the sanitizer will be less effective at killing microbes that cause foodborne illness. After applying a sanitizer, allow enough contact time (the amount of time specified on the label that the sanitizer needs to be on the item before it’s considered sanitized) with bins/sinks/tables before stacking/nesting them. **ALWAYS follow label instructions.

How do growers choose a sanitizer and use it correctly?

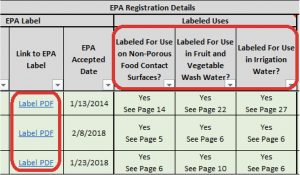

Sanitizers are typically regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Only use an EPA approved sanitizer formulated for your intended use (e.g., food contact surfaces, vegetable wash, irrigation water, etc.). Make sure it has an EPA number on the label. The label is the law so follow the directions carefully, only using it for what the label describes. Does the label say, “use for washing fresh produce” or “use for sanitizing non-porous food contact surfaces”? Is that what you intend to use it for? If the label does not reasonably describe your intended use, it is probably the wrong type of sanitizer. If you are an organic farm, check with your certifier before using any new materials.

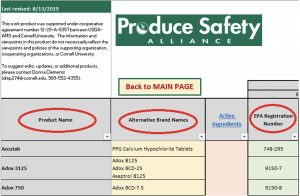

Please refer to the document from the Produce Safety Alliance (PSA) for comprehensive assistance in choosing a sanitizer that is appropriate for your operation. As a quick guide to choose a sanitizer, follow these steps:

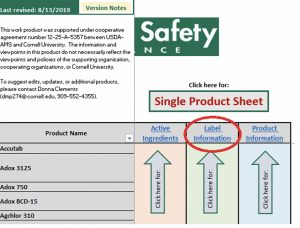

- Download the PSA sanitizer Excel tool. Open the spreadsheet and click on “Label Information.”

What are the common types of sanitizers and how should growers prepare them?

When choosing a sanitizer for your produce wash water, consider its safety for workers and the environment, stability, its effect on water quality, pH, and corrosiveness. Check label information to make sure to only use sanitizers that are approved for use on food contact surfaces and/or for washing produce, depending on your needs and wash system. The manufacturer is a good resource when determining whether a specific sanitizer is safe for your operation. Don’t be afraid to contact them!

- Chlorine – Hypochlorous acid – Sodium hypochlorite – Germicidal Bleach

- Chlorine is pH sensitive: when the pH of the wash water drops down to low pH levels there is a potential for toxic gas to form and at a high pH the bleach loses its efficacy against harmful microbes. The pH should be in the range of 6.5-7.5.

- Chlorine will bind to the organic matter in the wash water and reduce its effectiveness. Organic matter (soil and other debris) can make water turbid (cloudy). So, if the turbidity (cloudiness) of the water is too high (too cloudy), the chlorine will become less effective. Growers should monitor both turbidity and chlorine levels.

- Chlorine can be corrosive to equipment and can irritate the skin especially at levels above what is recommended for sanitizing. Measure accurately!

- To achieve 25ppm concentration using 6% Clorox Germicidal Bleach® for produce wash water, use Table 1 to determine how much Clorox® to use.

- PAA – Peroxyacetic Acid (PAA) with or without hydrogen peroxide – SaniDate® 5.0 (EPA #70299-19) or Oxidate® (EPA #70299-12) are the most common examples, but you should work with your chemical supplier to find which product would be the best for your use.

- This type of product is usually more expensive than bleach.

- PAA is less sensitive to pH or turbidity.

- PAA is non-corrosive to equipment and won’t irritate the skin at the low concentrations required in the produce wash water.

- Some of these products are approved for use in organic agriculture, check with your certifier.

- PAA wash water by-products are non-toxic, although the active ingredients can off-gas and smell very strong.

- To achieve 60ppm of PAA concentration using SaniDate® (5.3% PAA) for produce wash water, use Table 1 to determine how much SaniDate® to use.

| Gallons of Water |

Sanidate (5.3% PAA) | 6% Bleach (25 PPM available chlorine) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 tsp | ⅓ tsp |

| 5 | 1½ tbsp | ½ tbsp |

| 10 | 3 tbsp | 1 tbsp |

| 25 | ½ cup | 3 tbsp |

| 50 | 1 cup | ⅓ cup |

| 75 | 1⅓ cups | ½ cup |

| 100 | 1¾ cups | ⅔ cup |

Note: Other sanitizers with different concentrations of the active ingredients will have different values. Always make your calculations based on the concentration shown in the label.

What to monitor as you use sanitizers in your wash water

- The concentration of the Sanitizer: Know what concentration you need for how you are using the sanitizer. You need to know how to and how often to monitor the concentration.

- Test Strips: If you use test strips to monitor the concentration of sanitizer, make sure they are the ones that measure concentrations appropriate for the sanitizer you choose and for how you’re using it. For example, some test strips sold at pool supply stores will measure the concentration of total chlorine, instead of the desired free (available) chlorine. Additionally, some test strips are not effective because they do not read low levels of the active ingredient. You also want to make sure you have a test strip that will have concentrations larger than the highest concentration allowed for your use so you can check if your sanitizer is too concentrated.

- Oxidation-Reduction Meter (ORM): You can also get an ORM to use to monitor the concentration of the sanitizer in your wash water.

You should be testing your wash water at regular intervals as you are using the sanitizer. When needed, drain your wash water and start with fresh wash water with sanitizer for the next batch.

- Turbidity and pH: You should also be monitoring your wash water for turbidity and pH. Turbidity is a measure of how cloudy your water is getting from the soil and other organic matter that accumulates after dunking produce. High turbidity is an indication that excess organic matter may have caused the sanitizer to lose efficacy and at this point is no longer killing microbial contaminants. It’s best practice to change out your wash water on a regular, as-needed basis depending on how cloudy your water is getting. Wash water pH can also change as it gets more turbid. To monitor pH, you can use test strips or a pH meter.

- Water temperature: Water temperature is important to monitor as you are washing your produce. The temperature of the water should be cool, but not too cold. If it’s too cold the sanitizer might become less effective. If it’s too warm it may encourage the growth of some pathogens and diseases. The ideal temperature ranges from 55 degrees F to 120 degrees F (with the lower end of the range good for washing vegetables and the higher end of the range for sanitizing food contact surfaces). Make sure you check the label of the sanitizer to take note of the effective temperature range, if one is listed. NOTE: If you wash tomatoes, melons, peppers, or apples, as a rule of thumb, the water temperature should not be more than 10 degrees F cooler than the interior of the produce. If the water is colder, the water and any pathogens in the water can be sucked inside the fruit or vegetable and no amount of sanitizing will kill the interior pathogens.

You should be testing your wash water for sanitizer concentration, water pH, turbidity, and temperature at regular intervals as you are using the sanitizer. It’s best practice to keep track and document these readings when you are using a sanitizer on your farm. Monitoring water treatment (and documenting the readings) is required if your farm is covered under the FSMA Produce Safety Rule. Contact Dr. Robson Machado for assistance with sourcing any of the abovementioned equipment/supplies.

Conclusion

The overall goal when you wash your produce is getting your produce free of soil and debris. That way they will look nice for your markets. If you opt for adding a sanitizer in your wash, you might also increase shelf-life and reduce the risk of your produce being the source of foodborne illnesses by reducing cross-contamination. Nonetheless, washing produce and adding a sanitizer to your wash water is not mandatory. If you decide to do it, you should do it correctly.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Elizabeth A. Bihn and Ms. Donna Clements for their support and comprehensive feedback during the development of this factsheet.

Reviewed by Heather Bryant, Field Specialist, Food and Agriculture at UNH Cooperative Extension, Mary Saucier Choate, Field Specialist, Food Safety, Food & Agriculture at University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension, Leah Cook, Food Inspector Supervisor, Maine Department of Conservation Agriculture and Forestry, Caleb Goossen, Organic Crop and Conservation Specialist, Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association, and Jason Lilley, Sustainable Agricultural Professional, University of Maine Cooperative Extension

Resources

Callahan, C. 2020. UVM Extension Ag Engineering: A Guide to Cleaning, Sanitizing, and Disinfecting for Produce Farms. blog.uvm.edu/cwcallah/2020/03/30/clean-sanitize-disinfect/

Hadad, Robert. 2018. Cornell Cooperative Extension: How to Wash Produce with a Peracetic Acid Solution. rvpadmin.cce.cornell.edu/uploads/doc_676.pdf

National Pesticide Information Retrieval System website. npirspublic.ceris.purdue.edu/state/Default.aspx

Penn State Extension: Reasons for Washing Fresh Produce. youtube.com/watch?v=Ee5xq_B79xs

Produce Safety Alliance: Cleaning vs. Sanitizing producesafetyalliance.cornell.edu/sites/producesafetyalliance.cornell.edu/files/shared/documents/Cleaning-vs-Sanitizing.pdf

Produce Safety Alliance: Introduction to Selecting an EPA-Labeled Sanitizer producesafetyalliance.cornell.edu/sites/producesafetyalliance.cornell.edu/files/shared/documents/Sanitizer-Factsheet.pdf

Produce Safety Alliance: Records Required by the FSMA Produce Safety Rule producesafetyalliance.cornell.edu/sites/producesafetyalliance.cornell.edu/files/shared/documents/Records-Required-by-the-FSMA-PSR.pdf

UMASS Extension: Produce Wash Water Sanitizers: Chlorine and PAA ag.umass.edu/sites/ag.umass.edu/files/fact-sheets/pdf/pssanitizerlawtonkinchlasept15.pdf

University of Minnesota Extension: Cleaning and Sanitizing Food Contact Surfaces drive.google.com/file/d/1zjUOnP39n_C_gxhZTxBK-DW3qdeQqqP4/view

University of New Hampshire Extension: Farm Food Safety— Cleaning and Sanitizing Food Contact Surfaces extension.unh.edu/resource/farm-food-safety%E2%80%94-cleaning-and-sanitizing-food-contact-surfaces

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2020

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

The University of Maine System (the System) is an equal opportunity institution committed to fostering a nondiscriminatory environment and complying with all applicable nondiscrimination laws. Consistent with State and Federal law, the System does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender, gender identity or expression, ethnicity, national origin, citizenship status, familial status, ancestry, age, disability (physical or mental), genetic information, pregnancy, or veteran or military status in any aspect of its education, programs and activities, and employment. The System provides reasonable accommodations to qualified individuals with disabilities upon request. If you believe you have experienced discrimination or harassment, you are encouraged to contact the System Office of Equal Opportunity and Title IX Services at 5713 Chadbourne Hall, Room 412, Orono, ME 04469-5713, by calling 207.581.1226, or via TTY at 711 (Maine Relay System). For more information about Title IX or to file a complaint, please contact the UMS Title IX Coordinator at www.maine.edu/title-ix/.