Bulletin #6105, Thinking Together: Making Better Decisions in Groups

GroupWorks: Getting things done in groups

Bulletin #6105, Thinking Together: Making Better Decisions in Groups (PDF)

This fact sheet was developed by Extension Educator Ronald Beard, University of Maine Cooperative Extension.

For information about UMaine Extension programs and resources, visit extension.umaine.edu.

Find more of our publications and books at extension.umaine.edu/publications/.

Table of Contents

- What you will learn

- Debate versus dialogue

- Can we draw it?

- Do it, and check in about it

- Negotiate—with principles

- Will a facilitator help?

- Summary

- Additional resources

What you will learn:

- Some conditions for effective decision-making in groups

- A process for a group making a decision

- Ingredients for consensus decision-making

- What helps while you are making decisions in groups

When was the last time you felt good helping your group decide something meaningful? Was it a simple vote, or was there good discussion beforehand? Did people understand what was being decided? Did you look at more than one possible way to solve the problem or move ahead with an opportunity? Did everyone have a chance to talk? Did you talk about the obvious issues as well as those that are sometimes “undiscussable” in your group? Was there a sense of celebration when you finally made the decision?

Debate versus dialogue

Did you know that the word debate comes from the French “to beat”? Even “discussion” comes from a root word meaning “to break things up.” In contrast, the word dialogue has a meaning more like “. . . a free flow of meaning among all participants.”1

Box 1 illustrates some of the differences between debate and dialogue.

Groups that aim for dialogue in making decisions believe they have heard more than facts. They have a greater understanding about the meaning of the facts, experiences and feelings shared in the process of making a decision.

Can we draw it?

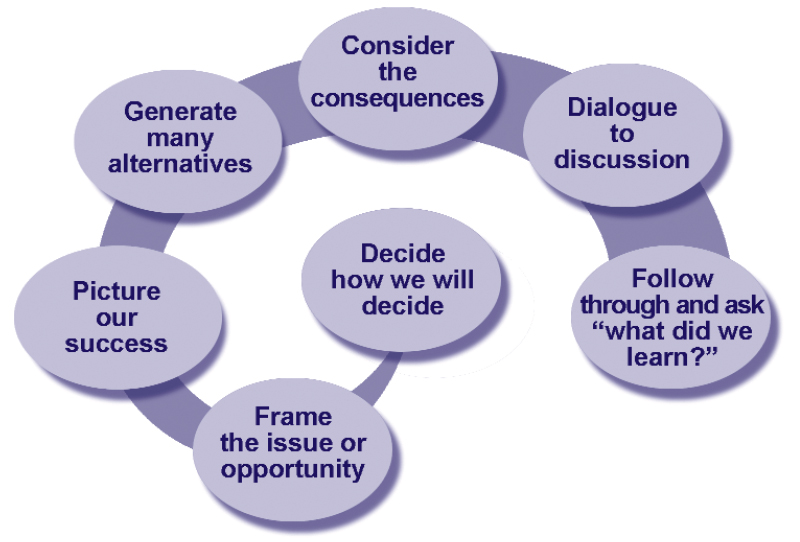

Groups who make decisions on a regular basis are able to draw the process they use. A flow chart of how decisions are made is useful as a reminder to new as well as experienced members of your group. Some decisions may come in simple votes, and some are made after being studied by a committee that makes recommendations. With fairly complex issues, your group may want to consider the process outlined below, which is summarized in Chart 1.

Can we frame it?

Groups often begin by clarifying the problem or opportunity around which decisions need to be made. Framing the issue is often the first step in the process. If all members of a group come to understand the issue in the same way, there is a better chance that a common vision of a solution or course of action will emerge.

How will we decide?

Eventually, a group will make a decision. Often they’ll choose by voting, in which some will “win” and others may “lose.” But if the decision is truly important, the group may want to use “community consensus.” (See Box 2) It is important to say which form of decision-making your group will use early on in the process so that people know something about how much time and energy the process will take. Deciding how to decide is an important step in the process.

Can we picture success?

Given the newly framed issue, you might acknowledge the group’s history core beliefs. (What are we proudest about? What do we want to carry forward in this decision?) These beliefs or values might suggest what the group would see as a picture of success in resolving the present issue. Listing some of the criteria for success will give the group something against which to measure alternative solutions.

Sketch many alternatives

After framing an issue and envisioning success, effective groups involve everyone in thinking about all the possible alternatives for addressing the issue. Be creative and list as many solutions or approaches as possible. It’s time for thinking “outside the box,” not limited by the past or present problems, or worries about money.

If we choose this, what might happen?

Each alternative listed has a number of possible consequences, which can be listed as well. And each consequence can be judged against earlier criteria for success. This step narrows down the alternatives by weighing the consequences against the criteria for a successful outcome.

After listing and discussing the consequences, ask the members of the group which alternatives they are ready to release and which they want to keep.

More dialogue . . . leading to decision

Through continued conversation about the alternatives, the group may be able to narrow the choices to two or three, with the advantages and disadvantages of each. Individuals will want to share what they think and what they feel about the alternatives. Eventually, you’ll be ready to make a choice. If you’ve already decided on a majority decision, then a vote is in order. If you have opted for a community consensus decision, you will test solutions until there is agreement to move ahead. In this style of decision-making, not everyone will agree, for consensus does not require unanimous support. Work until no one feels so strongly that they would stand in the way of the group moving forward. When your group has made a decision, write it down. Make it part of the record so the actual terms of the agreement can be revisited as needed.

Do it, and check in about it

The process isn’t really complete until the group goes ahead with the decision and observes the actual results, the positive outcomes and the not-so-positive outcomes. Effective groups revisit their big decisions from time to time and ask them-selves “what did we learn from that?” or “what meaning should we take forward about that?”

Who should be involved in decision-making? Well, it depends . . .

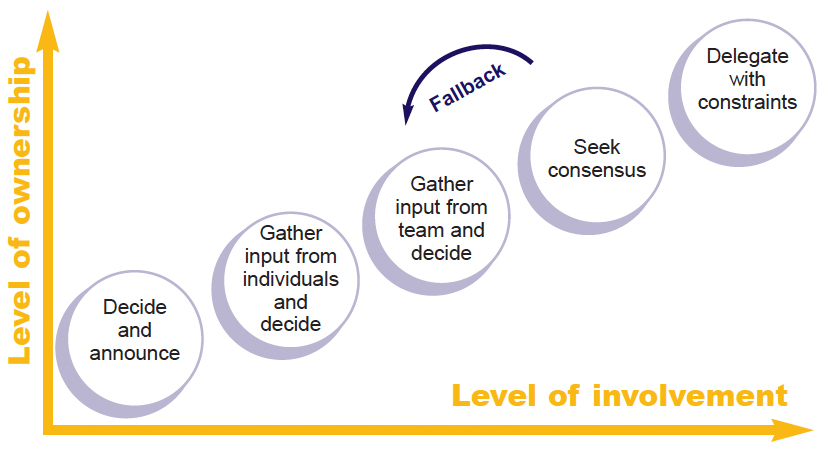

Sometimes decisions are made at different levels in a group or organization. We might have experienced being in a group where a leader has decided something and announced it to everyone else. We may feel quite differently about our support for that decision than a case where we worked through community consensus. In general, according to David Straus, the greater the level of involvement by members of a group or organization, the greater the level of ownership or support for a decision. (See Chart 2.) Decisions made by consensus often result in a higher level of support than decisions made by majority vote, where some participants may feel like they “lost.”

So, should you involve everyone? The answer is based on how important it is to have a decision that has strong support. It has to do with how much time you feel you can invest and the extent to which involving everyone is best for the long term relationships that keep a group or organization healthy.

Negotiate—with principles

You might have heard about or read a book called Getting to Yes. Its authors bring years of experience from the field of mediation, which aims at mutually agreed-upon solutions to a problem or dispute, and negotiation, in which parties work out compromises to disputes. Roger Fisher and William Ury suggest four principles that help in any dialogue leading to group decisions:2

- Separate people from the problem (even if people are having disagreements).

- Focus on interests, not positions.

- Invent options for mutual gain.

- Insist on using objective criteria (to decide what is best).

Putting each of these ideas into practice reinforces the belief that groups can build skills to make better decisions. Your group might add these to a list of ground rules that it uses to guide its work together. Some additional ground rules are noted in Box 4.

Will a facilitator help?

Not all groups need facilitators to make decisions, but facilitative leadership usually helps. That kind of leadership helps groups move through a process like the one outlined above. A facilitative leader does not have a vested interest in a particular outcome and tries to create a safe meeting space where everyone feels able to participate in making the decision. Facilitative leadership can often discover common interests among people who take different positions. This kind of leader is “in service” to the group. For more about “servant leaders” and facilitation, see the resource section.

Summary

We have outlined a process that results in decisions that people feel part of and will support. We have suggested some conditions for effective dialogue that lead to good decisions, including some hallmarks for consensus decisions. Using these approaches will lead to generally better decisions, healthier groups and healthier organizations. For more help with meetings and groups, check out our other our GroupWorks fact sheets and the resources noted in the footnotes and below. (See Box 3)

Additional resources

Greenleaf, Robert K. Don M. Frick and Larry C. Spears, Eds. On Becoming a Servant Leader. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1996.

Kelsey, Dee and Pam Plumb. Great Meetings! How to Facilitate like a Pro. Portland, ME: Hanson Park Press, 1997.

Donaldson, Gordon A., Jr. and David R. Sanderson. Working Together in Schools. Thousand Oaks, California: Corwin Press, 1996.

Bohm, in Joseph Jaworski, Synchronicity (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1998), 110.

Roger Fisher and William Ury, Getting to Yes (New York: Penguin Books, 1991)

Box 1: A comparison of dialogue and debate

Dialogue Debate Dialogue is collaborative: two or more sides work together toward common understanding. In dialogue, finding common ground is the goal.

Debate is oppositional: two sides oppose each other and attempt to prove each other wrong. In debate, winning is the goal.

In dialogue, one listens to the other side(s) in order to understand, find meaning and find agreement. Dialogue enlarges and possibly changes a participant’s point of view.

In debate, one listens to the other side in order to find flaws and to counter its arguments. Debate affirms a participant’s own point of view.

Dialogue opens the possibility of reaching a better solution than any of the original solutions. Dialogue creates an open-minded attitude: an openness to being wrong and an openness to change.

Debate defends one’s own positions as the best solution and excludes other solutions. Debate creates a closed-minded attitude, a determination to be right.

Excerpted from Sarah vL. Campbell, A Guide for Training Study Circle Facilitators (Pomfret, CT: Topsfield Foundation, 1998), 33 (accessed December 2003 from 12/15/03 from http://www.studycircles.org/pdf/training.pdf).

Box 2: Community consensus

Ingrid Bens identifies the following ingredients of a consensus process:

- There are multiple ideas being shared.

- Individual feelings are openly explored.

- Everyone is heard.

- There is active listening and paraphrasing to clarify ideas, and ideas are built on by other members.

- No one is trying to push a pre-determined solution; instead there is an open and objective quest for new options.

- The final solution is based on sound information.

- When the final solution is reached, individuals are satisfied they were part of the decision.

- Everyone feels consulted and involved; even if the final solution isn’t the one they would have chosen working on their own, they can “live with it.”

Source: Ingrid Bens, Facilitating With Ease! (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2000), 118.

Box 3: Personal and group pointers for good dialogue and decision-making

Rick Ross, a consultant to businesses and organizations, suggests the following practices for improving decision-making.

- Pay attention to your intentions. Be clear about what you want out of this decision. Note that what you want out of the decision isn’t a particular solution, but rather what would be gained from a successful solution.

- Balance advocacy with inquiry. In the dialogue that leads to a decision, make sure you share facts, experiences and feelings. Explain why you feel the way you do, and then ask others to share information and feelings so that you can better understand them.

- Build shared meaning. We all have pictures of the world, based on our experience. Your experience may differ from your neighbor’s and therefore you are likely to have different pictures of the way the world works. In dialogue you are trying to build a shared picture, a model of the world that you build together. To get clear about your models of the world, ask if there are any hidden assumptions that, if revealed, might make things clearer.

- Use self-awareness as a resource. At various times in the dialogue, you may find yourself feeling frustrated, angry, confused, hopeless. If you can, step back from those feelings to look below the surface, and without blaming anyone, ask the group to help you with your concerns and what might have led you to those concerns and feelings. Modeling this technique may inspire others to do the same, helping the group to move on.

- Explore impasses. Every so often, the group will bog down and you will feel heavy, unable to move forward because of disagreements. Take time to list the areas where there is agreement and disagreement and ask a question like “what is preventing us from moving forward right now?”

Source: Rick Ross, “Skillful Discussion,” in Peter Serge, The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook (New York: Doubleday, 1994), 387.

Box 4: Ground rules

Ground rules help assure that behavior in the group is aligned with getting the work done AND maintaining good relations. Here are some ground rules that have proven useful:

- Share the “airtime.”

- Speak one at a time.

- Ask questions in order to understand.

- Disagree openly and respectfully.

- Attend to time and topic.

Each group can discuss what ground rules will be useful. Once a group agrees on ground rules, it is often helpful to post them at each meeting. When ground rules are visible, any group member can reflect on them and gently remind others if they are not being followed.

Source: Ingrid Bens, Facilitating With Ease! (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2000), 118.

1 Bohm, in Joseph Jaworski, Synchronicity (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1998), 110.

2 Roger Fisher and William Ury, Getting to Yes (New York: Penguin Books, 1991)

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2004

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

In complying with the letter and spirit of applicable laws and pursuing its own goals of diversity, the University of Maine System does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender, gender identity or expression, ethnicity, national origin, citizenship status, familial status, ancestry, age, disability physical or mental, genetic information, or veterans or military status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The University provides reasonable accommodations to qualified individuals with disabilities upon request. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Director of Equal Opportunity, 5713 Chadbourne Hall, Room 412, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5713, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).