Master Gardener Volunteers Newsletter Hancock County – May 2024

Table of Contents

GETTING TO KNOW MG ADVISORY / MEET GREG MEKRAS / MEET HEIDI WELCH / SUNDIAL LUPINE / FAVORITE TOOLS / TIME TO CLEAN YOUR TOOLS!

Upcoming Dates to Remember!

May 8 MGV Project Leader Orientation – update/Zoom

May 11 BHNG – Tool Sharpening Workshop

May 25 Field Trip – Wild Gardens of Acadia

May 27 Memorial Day – office closed

June 1 Native Gardens of Blue Hill – Plant Sale

GETTING TO KNOW OUR MGV ADVISORY MEMBERS!

This month we continue introducing you to members of the Master Gardener Volunteer Advisory Committee (MGVAC)

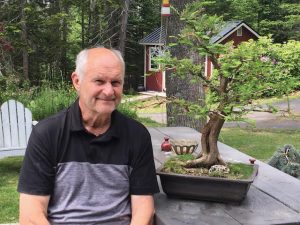

Meet Greg Mekras

Hi, my name is Greg Mekras and I have been a member of the Hancock County MGV Advisory Committee for 2 years. I currently live with my wife Valerie in Deer Isle, ME. In 2017 I retired after 35 years from Texas Instruments, Inc., located in Sugar Land, TX. She retired at the same time from her job as a PT working in a school system in Katy, TX. I went through the MGV training in 2019.

Designing and managing semiconductor chip development was very stressful for me, so I gravitated toward gardening and growing house plants as a form of stress relief. I started focusing on orchids and managed to kill them all by overwatering. I saw a bonsai exhibit at an Austin Japanese garden and decided to give it a try. I joined a Bonsai club in Houston and they explained that using a water retentive soil and excessive watering was my problem. I switched to growing my trees in almost 100% inorganic fired clay and lava rock and voila, success!

Maine climate with bonsai has been a new learning experience as many of my 100+ trees are not compatible with zone 5b. So, I fill up my basement with trees and grow lights. Always looking to make new friends through bonsai, so let me know if you are curious about this centuries-old art form.

I volunteer at Native Gardens in Blue Hill and have worked on developing the forest trails there. I currently serve on their Board in the role of Treasurer.

Meet Heidi Welch

“To plant a garden is to dream of tomorrow” Audrey Hepburn

How true!

As far as I can recall, I have always been drawn to nature. Digging in the “dirt” (as we called it back then) to make mudpies topped with salvia fuzzies as a child in Berkeley, California, and exploring the out-of-doors camping with my parents morphed into an interest in community gardening at Antioch College in Ohio and an early career in environmental education at Yosemite and Olympic National Parks. The opportunity to work as a naturalist at Acadia National Park landed me on MDI in 1976.

For some 40+ years I have made a home on the “backside” of Mount Desert Island where my partner and I maintain an organic vegetable garden and perennial beds with an eye to pollinators. In 2012, when I graduated from the world of financial remuneration to community volunteerdom, a friend highly recommended the MGV course and projects. I remember being quite intimidated by the application! The class (in person back in those days) was outstanding and the people were very friendly and interesting – I was hooked 🙂

My main MGV project from then to ongoing is at Sweet Haven Farm (in Seal Cove, on MDI) where we grow organic produce for Harvest for Hunger. Contributing healthy fresh food to people who otherwise wouldn’t have it is just plain satisfying. Plus, my workday cohorts are full of curiosity, fun, and eclectic conversation (and ginger snaps). Also fascinating are experiments with succession plantings, seed varieties, and ways to extend the growing season.

Over the years, I’ve worked on several MGV plant sales and have also been part of the Trenton Trail “native plants for your garden” project and designed the interpretive panel for the St. Dunstan’s pollinator garden project. Currently, I am serving a second round on the Advisory Committee and am part of the Continuing Education Committee. “Save the date: Saturday, May 25, 10 am, a field trip at Wild Gardens of Acadia.” It seems I wear my affection for this organization on my sleeve!

I love to encourage new gardeners to the MGV program and have come to appreciate that any good garden has weeds 😉

Maine’s Native Sundial Lupine

by Jan McIntyre (MGV -09′)

As tourists start descending upon Maine in spring, they are awed by the beautiful purple-blue flowers that grow in swaths along the highways. Most of them are unaware that this bigleaf lupine (Lupinus polyphyllus) is a non-native invasive plant from the West Coast of the U.S. Introduced in the 1950’s, it quickly spread, outcompeting many native plants.

While attending a lecture in 2019 given by Mark Richardson, who wrote Native Plants of New England, I learned that Maine once had its own native lupine, the sundial lupine (Lupinus perennis), which no longer grew here. Through further research, I found that it had once occurred in Aroostook, Knox, and Oxford Counties and had been extirpated from the state many years ago. Native and still growing in many U.S. states, it was once native to all of New England, but the only remaining native New England population is found at the Concord Pine Barrens in Concord, New Hampshire.

The sundial is the only host plant of the Karner Blue butterfly, which for years had been thought to have once occurred in Maine, but through forensic entomology, it was found that the documented Karner Blue butterfly specimen from Norway, Maine was actually a specimen from New York. At this point, no one can prove that the Karner Blue existed in Maine, nor can

they prove that it didn’t.

As beautiful as the bigleaf lupine is, it does not serve as a host plant for any of Maine’s native butterflies or moths. This is due to the fact that they do not share an evolutionary history, so the caterpillars of these butterflies and moths will die if they ingest the leaves. Unlike the invasive lupine, our native sundial lupine is a host plant for Maine’s Eastern Tailed-Blue (Cupido comyntas), Gray Hairstreak (Strymom melinus), and Clouded Sulphur (Cloias philodice) butterflies and the Phyllira Tiger moth (Apantesis phyllira).

The bigleaf and the sundial are both members of the Legume family and as nitrogen-fixing plants, they do add nitrogen to the soil. This should encourage and benefit the growth of other plants; but unlike the sundial, the bigleaf becomes the most dominant plant, crowding out our natives, which may be flowering at different times. The flowers of both species have pollen but contain no nectar, so once the pollen of the bigleaf has gone by, insects may have to travel long distances to obtain nectar.

soil. This should encourage and benefit the growth of other plants; but unlike the sundial, the bigleaf becomes the most dominant plant, crowding out our natives, which may be flowering at different times. The flowers of both species have pollen but contain no nectar, so once the pollen of the bigleaf has gone by, insects may have to travel long distances to obtain nectar.

Both species of lupine look very similar, but on closer observation, there are ways to tell the two apart.

The sundial lupine only grows to about one foot tall, has 7-11 leaflets, and the leaves are about 2” long and ½” wide. The flower stalk, which only produces purple-blue flowers, is under two feet tall. Sundial seeds are white or cream-colored. It will not grow well in moist soil, preferring drier sandy areas in sun or part shade.

The non-native bigleaf lupine grows taller than one foot, has 9-17 leaflets with each leaf being 4” long and 1-2” wide, and produces purple, white, and pink flowers on a flower stalk over 2’ tall. The seed color is black. It will grow in dry sandy soil but also tolerate moister soils. These two species can cross-pollinate, thereby creating plants that are unfit for ingestion by Maine’s native butterflies, so they should not be planted in close proximity.

The clamshell-like flowers of the sundial are pollinated by bumble bees (Bombus spp.), carpenter bees (Xylocopa virginica), mason bees (Osmia spp.), and leaf-cutter bees (Megachile spp.). Forcing themselves into the flower, pollen is collected and as they move from flower to flower, pollination takes place. Once pollinated, the flower color changes and is accompanied by a reduction in the amount of pollen. The color of a newly-opened flower bud starts out white to very light purple and as each flower is pollinated, the color changes to a darker purple blue. This change is recognized by pollinators who seek out the lighter banner petal color which has the most pollen. The color change evolved because it makes pollinator activity more efficient and enhances genetic diversity. The insects don’t waste time going to a flower with little pollen and the plant benefits by having more flowers pollinated. Color change may not be the only deciding factor of which flower to visit, but rather a change in the electromagnetic field around the flower, which we cannot observe. As the insect is collecting pollen, electroreception occurs, where pollen jumps from the flower to the insect due to the flowers being negatively charged and the insect, from flying has become positively charged. This magnetic charge may lessen once the flower has become pollinated, thus making it less attractive.

As a way to help re-introduce the sundial back to Maine, in October of 2019 the Bar Harbor Garden Club started a project called the Sundial Lupine Project (SDLL). Seeds were purchased from both the Wild Seed Project and Prairie Moon Nursery. The Wild Seed Project only sells sundial seeds in packets with 20 seeds each and with the volume that we needed, most of our purchases have been from Prairie Moon, where an ounce contains 1,100 seeds. Since the inception of the project, the club has grown over 5,000 sundial lupine plants which have been donated to various plant sales, sold, and then planted all over the state in private gardens. Plantings of the sundial have also been established at Garland Farm, the Blue Star Memorial Marker on Rte.3, Hulls Cove Visitor Center, and at College of the Atlantic, all in Bar Harbor Seeds have also been packaged up and distributed to participants at various gardening conventions throughout the state. Native Gardens of Blue Hill have also been planting and cultivating Sundial Lupines for the last few years and some of the vendor at their Native Plant Sale have their own for sale.

Sundial can be grown in pots at the end of February or early March as described below, or seeds can be planted in a prepared bed in November. Direct seeding works well, but the rate is not as good as raising the seeds in pots. If direct seeding, prepare an area free of weeds in a sunny area with sandy loam (at least 50% sand is good), spread your seeds in early November, and cover with a 1/4” layer of Quikrete All Purpose sand (obtainable at many hardware stores). Water well and walk away!

bed in November. Direct seeding works well, but the rate is not as good as raising the seeds in pots. If direct seeding, prepare an area free of weeds in a sunny area with sandy loam (at least 50% sand is good), spread your seeds in early November, and cover with a 1/4” layer of Quikrete All Purpose sand (obtainable at many hardware stores). Water well and walk away!

With either method, germination begins occurring in mid to late April and will continue sporadically for a few more months. The plants usually start flowering in the 2nd or 3rd year of their development, but in my experience, we have had plants in flower in late-July and August of the 1st year, and the following year flowering in their usual time frame around Memorial Day.

Seeding in Pots

– Time frame: End of Feb, Early March

– Use 3¼” pots. 4” wastes planting medium

– Moisten planting medium with enough water to make it feel like a damp sponge

– Fill pots with potting mix. Pack down to about ½” from rim of pot.

– Place 5 seeds per pot on top of mixture

– Cover with ¼” of sand

– Water in. DO NOT FERTILIZE.

– Put pots in trays and place them outside ASAP. Raise the tray a bit above ground (use rocks, or pieces of wood)

– Place them in shady, semi-shady areas so they are thoroughly exposed to snow, rain, wind, etc. This will allow them to be *scarified and *stratified.

– Best to cover with a piece of hardware cloth (or very open boughs) if possible to prevent wildlife interference. Boughs need to let snow and rain reach pots.

– Watch for germination in mid-April. Remove hardware cloth or boughs.

– When most have germinated move into sunny area and watch the weather and water as needed until planted.

*Scarified – breaking down of the seed coat either by environmental or mechanical means

* Stratified – exposure to cold temperatures for a certain length of time

Planting from the pots

Sundial lupine have long taproots, so plant mid-May to Mid-June in a sunny, sandy, spot. Later times can jeopardize success.

– Before planting, lightly water the pot to help hold the soil together. Remove soil and plants together as a whole from each pot. DO NOT SEPARATE PLANTS. Plant as a group that germinated in the pot. Germination may continue after planting.

– Water plants thoroughly and then water and weed as needed for their 1st growing season. Remember, DO NOT FERTILIZE.

– Plants occasionally will flower 1st season in July or August. From then on, will flower in May/June.

Favorite Tools Workshop

by Jane Ham

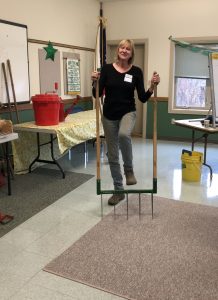

April 20th brought a morning of heavy rain. It didn’t dampen the enthusiasm of 17 gardeners who gathered at the Extension Classroom for this Continuing Ed Workshop, all with their favorite tools in hand.

Heidi Welch, MGV, developed and hosted the show-and-tell with a lively discussion of all types of tools. Lisa De Pasqual served as scribe, not only listing the variety of tools but in some cases drawing pictures of them.

Tom McIntyre gave a demonstration of the method he uses to break down vines and other large matter using a handmade wooden trough. Tom oversees the composting at Sweet Haven Farm in Seal Harbor.

Gaylord Sundt brought a 50 lb rock bar once used in railroad work and now used to break up and remove boulders.

Lisa DePasqual brought the broadfork she uses to create rows for planting at Brooklin Community Garden which she oversees. (See Photo)

Pier Carros finds a pick mattock handy for digging up roots and rocks around her home.

Phil Norris brought in 3, 4, 5, and 6-tined forks used for a variety of purposes on his Clayfield Farm and Orchard in East Blue Hill.

Mary Jude brought in her battery-operated small hand chainsaw which has made pruning a breeze.

Mary Doherty demonstrated a rather vicious-looking “toothed shovel” great for separating plants such as daylilies.

Many of the tools were antiques handed down over the years or picked up at yard sales. Some were new or slightly used such as the trusty hori hori knife which several folks favor for many uses in the garden. Each participant had a favorite hand tool for weeding and clipping.

Happy Spring! Time to Clean Your Tools

by Lynne Altvater

It’s time for that spring cleaning; washing comforters and curtains, woodwork and floors, but what about that garden shed?

If you are like me, the fall is full of last-minute garden needs. My potted annuals are still thriving, and I wait until the last possible minute to empty them into the compost heap. Then everything gets loaded into my greenhouse for the winter rather haphazardly.

But that untidy collection of pots, tools, and garden gloves could carry fungus and disease that could be transmitted to your awakening garden. Here are a few tips to keep your garden safe, and your tool shed sparkling!

Here’s what you will need:

Gardening gloves, putty knife, steel wool, 3 1/2 gallon plastic bucket, 1 Tbsp. dish soap, 2 cups bleach, 1 cup vegetable oil, 5 oz. can lighter fluid, all-purpose play sand, bleach-free disinfecting wipes, old towels, garden hose.

Empty out the tool shed onto the driveway or lawn. Run your collection of garden gloves, towels, and gardening jackets through a separate wash in the washer/dryer to have them clean and fresh and free of any bacteria.

Hose off then scrub your empty containers and pots with warm, soapy water.

For your TOOLS:

Remove Dirt: Using a powerful garden hose, knock the dirt off and go after any stubborn caked-on dirt with a putty knife.

Remove Rust: If your tools have any rust, give those areas a good scrub with steel wool.

Remove Sap: Dab a bit of lighter fluid onto a cloth and wipe the tools to remove sap.

Soak Tools: Once the caked-on dirt and grime have been removed, give the tools a good soak in a bucket of hot water. Add dish soap for an extra boost of cleaning.

Rinse and Dry: Rinse with clean water, then dry the tools with an old towel. Putting the tools away wet will cause them to rust prematurely.

Cleaning Maintenance: Rinse with clean water, then dry the tools with an old towel. Putting the tools away wet will cause them to rust prematurely.

Disinfect and Sanitize: If you have plants with fungal or bacterial problems, you should periodically disinfect your garden tools. Keep bleach-free disinfectant wipes handy to remove sap, bacteria or fungus from shears, so you don’t spread anything from plant to plant through your garden tools.

A quick soak in a bleach solution (two cups of bleach for every one gallon of water) can help curb the spread of annoying infestations. Just be sure to rinse and dry the tools thoroughly.

Now you are ready to get out there and garden!

- Photos courtesy of Lynne Altvater

The Sharpest Tool in the Shed: Tool Sharpening & Care Workshop

Native Gardens of Blue Hill Workshop

Saturday, May 11

9-11am

UMaine Cooperative Extension at Hancock County

63 Boggy Brook Rd, Ellsworth

Click here to pre-register (required) Workshop fee: $20*(See here for more info: https://www.nativemainegardens.org/upcoming-events

Space is limited, filling up quickly!

Native Gardens of Blue Hill 2024 Native Plant Sale

Saturday, June 1

9am-12pm

Live Shopping & Pre-order Pick-up

NGBH Gardens at Bagaduce Music, 49 South St, Blue Hill

Several area nurseries will be on site selling their sustainably-grown plants.

For more information: https://www.nativemainegardens.org/2024-spring-plant-sale

Take lots of pictures of your MGV projects!

Send them Sue Baez at sue.baez@maine.edu for use in the Recognition Event video

We are always on the lookout for articles you’d like to see here, or topics you would like to write about. Contact the Chair of the newsletter subcommittee at bluehilldesign@gmail.com.

This newsletter gets sent to 152 people every month. Do you know an MGV who doesn’t receive the newsletter and would like to? Let us know! MGVnewsletterinput@gmail.com

Thank you from

Betsy Adams, Mary Doherty, Nicole Gurreri, Jane Ham, Mary Hartley, and Jan Migneault.