Bulletin #5087, Early Blight of Potatoes and Tomatoes

Pest Management Fact Sheet #5087

By Dr. I. Kutay Ozturk, Assistant Extension Professor and Extension Potato Pathologist, University of Maine Cooperative Extension and Dr. Alicyn Smart, Associate Extension Professor and Extension Plant Pathologist, University of Maine Cooperative Extension

For information about UMaine Extension programs and resources, visit extension.umaine.edu. Find more of our publications and books at extension.umaine.edu/publications/.

Other Name: Alternaria Pathogen: Alternaria solani, Alternaria tomatophilia

Introduction

Early blight is one of Maine’s most common diseases, affecting potatoes and tomatoes annually in commercial agriculture and small gardens. This fungal disease can cause significant damage to plant health by infecting stems and leaves. It can also cause direct loss in yield by infecting tomato fruit and potato tubers; however, tuber early blight infections are uncommon in Maine.

Lifecycle

Early blight is caused by Alternaria solani, a fungus that can overwinter in infected crop residue (Figure 1). Unhealthy and stressed plants are most susceptible to the disease, especially as the plant matures. For the pathogen, the optimal temperature is 82 to 86 °F, and the optimal relative humidity (RH) is 80% or higher. The disease will likely develop for tomatoes if these environmental conditions are met and the pathogen and susceptible host are present. Young potato plants are typically not very susceptible to early blight until after tuber bulking begins. Rain is not a necessity for disease onset. A. solani spores can be transported by water, wind, insects, animals, and machinery. When an A. solani spore lands on a tomato or potato, it begins to germinate within two hours over a wide range of temperatures, but within the optimal range, it can take as little as a half hour. Depending on the temperature, the fungus requires another 3 to 12 hours to penetrate the plant. After penetration, lesions may form within 2-3 days, or the infection can remain dormant, awaiting proper environmental conditions (and extended periods of wetness) until symptoms develop. Sporulation occurs when the optimal temperatures and moisture (as provided by rain, mist, fog, dew, or irrigation) are present. Infections are most prevalent in poorly nourished or otherwise stressed plants but in tomatoes to a lesser extent. If the infected plants are not removed at the end of the season or incorporated into the soil to break down, the fungus can spend the winter in infected plant debris in or on the soil, where it can survive for at least one to several years. New spores are produced the following season from the infected debris from the season prior. Once the initial infections have occurred, the infected plant material becomes the most important source of new spore production and is responsible for rapid disease spread. Infected seeds can also be the cause of diseased plants.

Symptoms

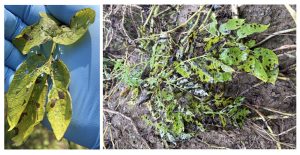

Early blight produces a wide range of symptoms and infects all plant parts above-ground and potato tubers. The most characteristic symptom of early blight is the bulls-eye pattern of disease lesions on leaves and stems. These leaf spots start small, then enlarge and become plentiful on the leaf until the leaf spots merge to cause larger areas of infection. In tomatoes, it can cause damping-off, collar rot, stem cankers, leaf blight, and fruit rot. The most common symptoms in potatoes appear as numerous bulls-eye-shaped lesions on the leaves (Figure 2). Early blight often infects the oldest leaves first and progresses upward, attacking newer tissue as the older leaves droop and dry out. Under severe epidemics, leaves may be killed prematurely, followed by stem infections and then fruit rot. Lower foliage of tomatoes tolerant to A. solani can get leaf spots, but the disease never progresses much further.

Cultural Control

- Use only clean seed saved from disease-free plants/certified seed potatoes.

- At the end of the season, remove and destroy crop residue. Where this is not practical, plow residue into the soil to promote breakdown by soil microorganisms and physically remove the spore source from the soil surface.

- Practice crop rotation to non-susceptible crops such as small grains or brassica crops for three years. Be sure to control plants that emerge from the previous year’s planting (volunteers).

- Maintain good weed management, especially weeds susceptible to the disease, such as hairy nightshade or black nightshade.

- Promote good air circulation by proper spacing of plants. This can be found on the seed container.

- Orient rows toward prevailing winds, avoid shaded areas and avoid wind barriers.

- Irrigate early in the day to promote rapid drying of foliage, and if possible, use drip irrigation to prevent foliage from getting wet.

- When pruning lower tomato leaves, clean the cutting tool with 70% rubbing alcohol to limit the spread of disease from one plant to another.

- Provide proper fertilization and mineral balance. Healthy plants with adequate nutrition are less susceptible to the disease.

- Minimize plant injury and the spread of spores by controlling insect feeding.

- In small fields, hand-picking diseased foliage may slow the rate of disease spread but should not be relied on for control. Do not work in a wet garden.

- Use resistant or tolerant tomato varieties such as Mountain Magic, Juliet, Defiant PhR, Verona, or Jasper. Check seed catalogs or packets for the “EB” designation, indicating resistance to early blight.

- Russet Burbank, Lamoka, Snowden, Lehigh, Ranger Russet, and Elba are among potato varieties with moderate resistance to early blight.

Chemical Control

For a disease to form, pathogen, susceptible host, and environmental conditions need to be present at the same time, forming the disease triangle. Since early blight is predominantly a late season potato disease, plant susceptibility is assumed to be present after a certain stage of plant development. Daily minimum and maximum temperatures are used to calculate physiological days (p-days). P-days measure the physiological development of the potato plant and are a better measure of the development of the potato plant than calendar days. The prediction of the onset of early blight on potatoes is based on the potato plants’ physiological days (p-days). Early blight risk is typically elevated after canopy closure and tuber bulking begins, which corresponds to approximately 300 p-days, and management actions are recommended beyond that point. Early maturing varieties, especially during seasons of high plant stress, such as extreme temperatures, may become susceptible to early blight sooner. P-day values are available from the University of Maine Cooperative Extension Potato Program.

Carefully review product labels before using and confirm whether they are labeled for use on the intended crop.

A wide variety of fungicides, including chlorothalonil and mancozeb, are available to control early blight. Please refer to the Potato Pest Control Guide for the most up-to-date list of fungicides available against early blight. A list of products that can be used for commercial tomato growing for both field tomatoes and greenhouse and high tunnel products can be accessed in the New England Vegetable Guide. Carefully review product labels before using and confirm whether they are labeled for use in tomatoes if tomato spraying is planned.

When Using Pesticides

ALWAYS FOLLOW LABEL DIRECTIONS!

Pest Management Unit Cooperative Extension Diagnostic and Research Laboratory 17 Godfrey Drive, Orono, ME 04473-1295 1.800.287.0279 (in Maine)

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2010, 2021, 2024

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

In complying with the letter and spirit of applicable laws and pursuing its own goals of diversity, the University of Maine System does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender, gender identity or expression, ethnicity, national origin, citizenship status, familial status, ancestry, age, disability physical or mental, genetic information, or veterans or military status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The University provides reasonable accommodations to qualified individuals with disabilities upon request. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Director of Equal Opportunity, 5713 Chadbourne Hall, Room 412, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5713, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).