Mosquito Biology

Pest Management Fact Sheet #5109

James F. Dill, Pest Management Specialist

Griffin M. Dill, IPM Professional

Charles D. Armstrong, Cranberry Professional & Staff Entomologist

In cooperation with Maine Department of ACF’s Insect and Disease Laboratory

For information about UMaine Extension programs and resources, visit extension.umaine.edu.

Find more of our publications and books at extension.umaine.edu/publications/.

That familiar buzzing in your ear, when you are trying to sleep on a summer’s night, or that uncomfortable bite? Mosquito! These annoying insects are widely distributed and known by all. Although there are over 40 species in Maine, less than half are considered biting pests of humans. However, one of the most common complaints from people enjoying the outdoors during the spring and summer months is the annoyance caused by the often enormous populations of these small, slender, long-legged flies coupled with the bites they inflict. For some, the most annoying part is the almost intolerable itching from the bites. Both males and females will use flower nectar for food, but it is only the females that feed on blood in order to obtain the required protein needed to produce and lay their eggs. During the biting process, the females can act as vectors of parasites and disease organisms such as malaria, yellow fever, and various forms of viral encephalitis; spreading them from one host to another. For example, heartworm (a disease of dogs caused by filarial worms) is transmitted by mosquitoes and is now established throughout most of New England. In the past, diseases carried by mosquitoes have usually not been considered a problem in Maine. Recently, however, concern has been expressed regarding the increased incidence in the Northeast of arboviruses (viruses carried by insects, ticks, and other closely related organisms) such as Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE), which was quite severe in 2009.

- Adult mosquito; photo by James Dill

- Mosquito larvae; photo by Griffin Dill

- Mosquito pupa; photo by Griffin Dill

In 1999, another form of encephalitis known as the West Nile Virus (WNV) was detected in the eastern US in New York City. This virus, which is deadly to the American crow and its relatives, is also a serious problem for horses and humans. By 2003, the virus had spread across the continental US and caused several hundred human deaths. Most people contracting the disease develop a mild case of “West Nile Fever” that resembles a mild cold or flu. Although Maine has had many dead, WNV-positive birds, the state has had very few human cases. As a result of increasing concerns of mosquito-borne viruses, a monitoring system has been developed for Maine mosquito species of concern, especially those species that can vector WNV and EEE.

In Maine, most of the nuisance biting mosquitoes can be placed into three broad groups based on their breeding habitat or where they are likely to cause the greatest problem. These three groups are: urban, woodland or salt marsh. A few additional species breed in more specific areas such as small stagnant ponds, bogs or swampy areas. Most mosquito vectors of encephalitis viruses are species that feed primarily on reservoir bird hosts, but which will readily bite humans or other mammals if given the opportunity. A partial list of potential vector species of mosquitoes known to be present in Maine include: Aedes vexans, Coquillettidia perturbans, Culex pipiens, C. restuans, C. salinarius, Culiseta melanura, Ochlerotatus japonicus, O. triseriatus and O. sollicitans.

Often species from other locations are accidentally introduced into new areas. One such introduced species is the Japanese rock pool mosquito, Ochlerotatus japonicus, also known as the Asian bush mosquito. Spreading rapidly throughout the Northeast, it was documented first in Connecticut in 1998, then quickly thereafter in New York and New Jersey. It was documented in Maine in 2000. It is a container-inhabiting species, so it is believed to have reached our shores most likely by way of some old tires destined for recycling. It is capable of breeding in tire dumps and discarded containers in urban areas. Although capable of carrying viruses, and in spite of its documented human blood feedings, this species has not yet shown itself to be an important arbovirus vector. Populations of this species are continuing to be monitored, however, as a precaution.

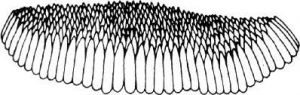

- Eggs

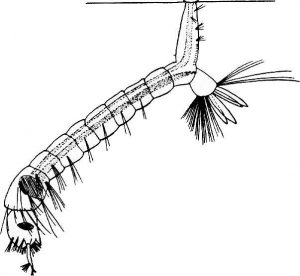

- Larva

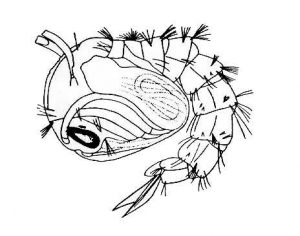

- Pupa

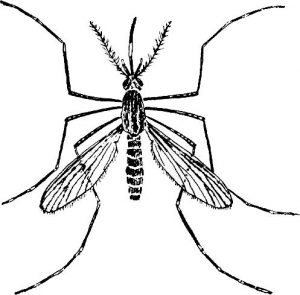

- Adult

- Adult in biting posture

Illustrations by James R. Baker, Insect and other Pests of Man and Animals, North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service.

Biology of Mosquitoes

All mosquitoes pass through four developmental stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Eggs are laid either in or near water, or in moist depressions that subsequently fill up with water in the spring (or by virtue of a flood). All larvae and pupae require water to develop to adulthood. The larvae of most species feed on microorganisms (including algae) and detritus, while some feed on other mosquito larvae. As larvae, most species need to be near the surface of the water in order to breathe. Depending on the species, the duration of the winter may be spent in any one of the four life stages. With the exception of salt marsh species, or an unusually wet year, one generation per year is the norm for the majority of Maine mosquito species. Adult mosquitoes may persist for weeks to even months, but the populations of all except for the salt marsh species usually start to decrease during hot and dry weather conditions. Adults move around in short flights and may on rare occasions move long distances of up to a few miles. Mosquitoes are usually the most active in the evening or on overcast days. During the day, they tend to remain resting on vegetation, taking flight only when disturbed by a suitable host. June is generally considered the prime month for woodland mosquitoes except in wet years when the season may be prolonged. Mosquitoes that appear briefly in the fall or spring (and occasionally during the winter) are females of species that overwinter as adults. The distribution and seasonality of Maine species is currently being studied.

Woodland (or Upland) Mosquitoes

The majority of our Maine mosquito species fall into the ‘woodland/upland’ category and most overwinter as eggs or larvae with only a single brood (single hatch) each year. In extremely wet seasons, more than one brood may occur. Some broods develop from shallow ponds, swamp pools and ditches, while others develop from temporary pools of water resulting from melting snow. Other breeding sites include rock pools, flood plain pools, and even tree holes. Contrary to popular belief, most mosquitoes will not breed in lakes or streams. Eggs normally begin to hatch in April or May. The tiny hatching larvae, which are also known as “wrigglers” or “wiggle tails,” are aquatic and undergo a few molts prior to pupation in May or June. Their rate of development increases with increasing temperature. In central Maine, emergence of the adults usually occurs in late May or early June. Upon emerging, female mosquitoes mate, seek blood, and deposit their eggs, all in the span of only a few days to as long as a few weeks, depending on the species. With the exception of unusually wet years, the eggs of most species remain dormant until the following spring.

Salt-Marsh Mosquitoes

Unlike the woodland mosquitoes, the salt-marsh mosquitoes (Aedes cantator and A. sollicitans) produce many generations per year and fly much longer distances in their search for food (up to twenty miles or more from the coast). These species breed only in saline pools in (or near) salt marshes. Eggs are deposited in and amongst depressions. Once the depressions are submerged following heavy rains, floods or high tides, the eggs hatch. As a rule, the frequency of high-run tides determines the frequency of generations; one generation of mosquitoes per high-run tide. With each generation, the numbers of individuals increase greatly. In some seasons, there may be two high-run tides each month with a new generation of mosquitoes with each one. A third, more southern salt-marsh mosquito, Aedes taeniorhynchus, probably occurs in southwestern Maine as well.

Urban Mosquitoes

Most mosquitoes can be found at one time or another in urban areas, but there is a special group of mosquitoes whose habits tend to bring them into urban settings with greater frequency. These are the mosquitoes that breed in water that has collected in an assortment of containers, from tin cans and tires, to birdbaths and dumpsters. These species also frequently feed on birds and a variety of mammals and can transmit arboviruses to humans. This group includes two of the more common WNV vectors, Culex pipiens and C. restuans as well as the suspected vector C. salinarus. Tree hole mosquitoes such as Aedes hendersoni and A. triseriatus. Ochlerotatus japonicus would also be included in this group.

When Using Pesticides

ALWAYS FOLLOW LABEL DIRECTIONS!

Pest Management Unit

Cooperative Extension Diagnostic and Research Laboratory

17 Godfrey Drive, Orono, ME 04473

1.800.287.0279 (in Maine)

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2011, 2018. Reviewed & updated by Charles Armstrong, Staff Entomologist: 2023.

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

In complying with the letter and spirit of applicable laws and pursuing its own goals of diversity, the University of Maine System does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender, gender identity or expression, ethnicity, national origin, citizenship status, familial status, ancestry, age, disability physical or mental, genetic information, or veterans or military status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The University provides reasonable accommodations to qualified individuals with disabilities upon request. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Director of Equal Opportunity, 101 Boudreau Hall, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5754, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).