Lost to the Sea: Maine’s Ancient Coastal Heritage

Jacquelynn Miller is a graduate student and research assistant at the School of Earth and Climate Sciences. Dr. Alice Kelley is an instructor in the School of Earth and Climate Sciences and an associate research professor in the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine.

Climate-driven sea-level rise and coastal erosion threaten ancient climate records stored within over 2000 shell middens along the coast of Maine. Created by Maine’s past aboriginal residents, these features consist of centimeters to meters of clam and/or oyster shell, other faunal remains, and artifacts. Shell middens provide a high-resolution snapshot of approximately 3000 years of environmental conditions and archive a record of human coastal adaptation for the same period.

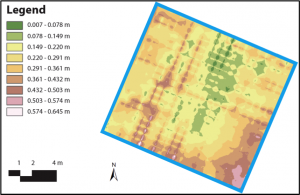

As these cultural and climate records are rapidly lost to coastal erosion, it is essential to develop a rapid method for characterizing these important sites and quantify the risk of erosion. This project seeks to accomplish that goal by using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to determine shell midden extent and thickness, as well as measuring erosion rates at representative sites along the coast. This project is a collaborative effort between researchers at the University of Maine and Maine State Archaeologist, Dr. Arthur Spiess, Maine Historic Preservation Commission (MHPC). The results from work at each site will be incorporated into site protection, preservation, and rescue planning for MHPC.

Summer 2016 field work was centered around reconnaissance to determine suggested site’s suitability for GPR survey. Approximately 10 sites, from Southern Maine to Downeast were visited. In one case, a previously identified site was completely lost to erosion. At other sites shells littered the beach, indicating on-going erosion. Additionally, three GPR surveys were completed. At each location, use of GPR indicated that the site was larger than previously recorded, but that the densest accumulation of shells and cultural material had been largely lost. A shoreline change analysis was conducted for the three sites surveyed during the summer 2016 field season. While using standard techniques, the results of this study indicated a need for alternative methods of shoreline change investigation. Analysis of the summer’s efforts produced a streamlined protocol for data collection, compilation, and presentation. Analysis of one site has successfully been completed using the new protocol, with work on the remaining sites underway.

Plans for the summer 2017 field season include data collection and processing at approximately five additional sites. A stakeholders meeting involving state and international experts, and a field trip, will occur in August to develop monitoring and rescue strategies for these important sites.

We are looking forward to the summer of 2017 field season!

By Jacquelynn Miller and Dr. Alice Kelley, May 2017.

Read a blog post by Jacquelynn describing her perspective on conducting field work in Maine on the Maine Sea Grant website.