Bulletin #1010, Equine Facts: Body Condition Scoring for Your Horse

Developed by Craig H. Wood, Department of Animal Sciences, College of Agriculture, Cooperative Extension Service, University of Kentucky. Adapted and reprinted with permission.

Updated by Rachel White, Ph.D., Assistant Extension Professor, Sustainable Agriculture and Livestock Educator, University of Maine Cooperative Extension (2025).

For information about UMaine Extension programs and resources, visit extension.umaine.edu.

Find more of our publications and books at extension.umaine.edu/publications/.

In a world where millions of people are taking steps to improve their own physical condition in order to live healthier lives, it only stands to reason that this same concept would be applied to other aspects of their lives and businesses. The ability to accurately assess a horse’s body condition, which is vital to its welfare, weighs heavily on the horse owner.

The old saying “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder” has never been more appropriate than in the body condition of horses. Beauty in one owner’s eye is fat in another’s. Hence the problem: What is the appropriate body condition of a horse, and what would be acceptable to the industry? A body conditioning scoring system developed by Dr. Don Henneke has served to provide a standard scoring system for the industry which can be used across breeds and by all horse people. The system assigns a score to a particular body condition (1 to 9) (Table 1) as opposed to vague words such as “good,” “fair,” “bad,” or “poor,” which leave differences in interpretation to the eye of the beholder.

The horse’s body condition measures the balance between intake and expenditure of energy. Body condition can be affected by a variety of factors such as food availability, reproductive activities, weather, performance or work activities, parasites, dental problems, and feeding practices. The actual body condition of a horse can also affect its reproductive capability, performance ability, work function, health status, and endocrine status. Therefore, it is important to achieve and maintain proper body condition. In order to do this, one must evaluate body fat in relationship to body musculature. In Maine during winter, a horse’s thick hair coat may hide the fact they are thin. Without extra energy in the winter to stay warm, horses can starve.

Body Condition Scoring System

The system developed by Dr. Henneke assigns a numerical value to fat deposition as it occurs in various places on the horse’s body. The system works by assessing fat both visually and by palpation (examination by touch), in each of six areas. Horses accumulate fat in these areas in a set order. For instance, a horse that scores 7 will have the same amount of fat as any other horse that scores 7, whether the horse is a thoroughbred, quarter horse or Arabian.

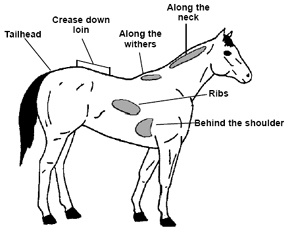

Fat is assessed in the following areas: the loin, ribs, tailhead, withers, neck, and shoulders (Figure 1). A numerical value is assigned based on the cumulative fat in all six areas (Table 1).

Loin: An extremely thin horse will have a negative crease and a ridge down the back where the spinous processes projects up. No fat can be felt along the back of the horse. However, this is one of the first areas to fill in as a horse gains weight. Fat is first laid down around body organs, then along the base of the spinous processes. As the horse gets fatter, an obvious crease or depression forms down the back because of fat accumulation along with the spinous processes.

Ribs: The next place to look is in the ribs. Visually assess the rib area, then run your fingers across the rib cage. A very thin horse will have prominent ribs, easily seen and felt, with no fat padding. As the horse begins to gain weight, a little padding can be felt around the ribs; by level 5 the ribs will no longer be visible but can be easily palpated by passing a hand down the rib cage. Once the horse progresses towards obesity, feeling the ribs will be impossible. Visible ribs on weanling or yearling horses can be normal. To assess a young horse, ideal body condition should be about one-third to one-half of fat covering the length of the rib cage.

Tailhead: In a very thin horse up to a number 3, the tailhead is prominent and easily discernible. Once the horse starts gaining weight, fat fills in around the tailhead. Fat can easily be palpated, and as the horse becomes obese, the fat will feel soft and begin to bulge.

Withers: Conformation of the withers may affect your assessment of body condition. The prominence or sharpness of the withers may vary between breeds; a thoroughbred typically has more prominent withers than a quarter horse. However, if a horse is very thin, the underlying structure of the withers will be easily visible. At a level 5, the withers will appear rounded. At levels 6 through 8, varying degrees of fat deposits can be felt along the withers. In obese horses, the withers will be bulging with fat.

Neck: The neck allows for refining the assessment of body condition. In an extremely thin horse, you will be able to see the bone structure of the neck, and the throatlatch will be very trim. As the horse gains condition, fat will be deposited down the top of the neck. A body condition score of 8 is characterized by a neck that is thick all around with fat evident at the crest and the throatlatch.

Shoulder: The shoulder will also help you refine the condition score, especially if conformation factors have made some other criteria less helpful. As a horse gains weight, fat is deposited around the shoulder to help it blend smoothly with the body. At increasing condition scores, fat is deposited behind the shoulder, especially in the region behind the elbow.

Putting the System to Work

Once body condition scores have been determined for your horses, how can you tell what is too fat or too thin? It has been suggested that the optimum score is a 5. This horse has some fat but has not yet reached the fleshy point. A horse below a 5 may have fat stores too low to maintain a healthy status if stressed. Body fat reserves are important to the overall health of a horse because fat represents energy reserves that can be used during periods of stress. Horses at a 3 or below have virtually no fat reserves; if more energy is needed, protein is broken down from muscle to meet energy requirements. In addition to increasing the quantity of feed, horse owners should consider checking their horse’s teeth, treating for internal parasites and evaluating their horse’s health status.

If a horse is exposed to extreme cold, lactation, or some other severe stress, a condition score of 6 or 7 would be desired. A horse can easily burn a great deal of fat in a short period of time in a high-stress situation. Body fat also plays a role in reproduction. Mares with a body condition score of 3 or below develop endocrine imbalances and have difficulty conceiving.

Horses with high condition scores are also predisposed to problems, but the problems are less immediate than those of a horse in poor body condition. Fat horses tend to be less agile performers and tire more quickly than trimmer horses. Fat horses are also more prone to colic and laminitis. Extremely fat horses may also have endocrine problems, they may be hypothyroid and show a deficient metabolic rate, which most likely is one reason they are fat.

One more factor you should consider when assigning a body condition score is the basic body type of your horse. Some horses, usually the easy keepers, just tend to carry more body fat than others. A horse that always seems to score a 7 or 8, despite attempts to lower the horse’s weight, may be perfectly healthy at that score. Additionally, the horse may require more exercise to keep muscles in shape.

This body condition scoring system will by no means tell you how fit your horse is for performance. Although horses in training will have less fat due to their exercise intensity, the fat level has nothing to do with muscle tone, cardiovascular fitness, or any other measure of athletic conditioning. The scoring system also does not distinguish between types of fat deposited.

You Make the Call

Determine the body condition of the following three horses based on the system in Table 1.

(Click on each separate image to enlarge.)

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2002, 2025

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

In complying with the letter and spirit of applicable laws and pursuing its own goals of diversity, the University of Maine System does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender, gender identity or expression, ethnicity, national origin, citizenship status, familial status, ancestry, age, disability physical or mental, genetic information, or veterans or military status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The University provides reasonable accommodations to qualified individuals with disabilities upon request. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Director of Equal Opportunity and Title IX Services, 5713 Chadbourne Hall, Room 412, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5713, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).