Bulletin #2576, Native Trees and Shrubs for Maine Landscapes: Common Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana)

Developed by Marjorie Peronto, Associate Extension Professor, University of Maine Cooperative Extension; and Reeser C. Manley, Assistant Professor of Horticulture, University of Maine.

For information about UMaine Extension programs and resources, visit extension.umaine.edu.

Find more of our publications and books at extension.umaine.edu/publications/.

Go native!

This series of publications is the result of a five-year research project that evaluated the adaptability of a variety of native trees and shrubs to the stresses of urban and residential landscapes in Maine. Non-native invasive plants pose a serious threat to Maine’s biodiversity. Plants such as Japanese barberry, shrubby honeysuckle, and Asiatic bittersweet, originally introduced for their ornamental features, have escaped from our landscapes, colonizing natural areas and displacing native plants and animals. By landscaping with native plants, we can create vegetation corridors that link fragmented wild areas, providing food and shelter for the native wildlife that is an integral part of our ecosystem. Your landscape choices can have an impact on the environment that goes far beyond your property lines.

Description

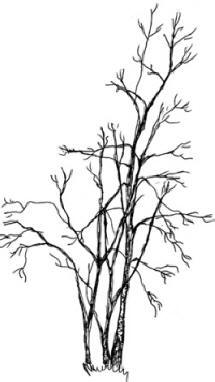

Form: a colonizing shrub or small tree, often multi-stemmed

Size: 35 to 50 feet high, 20 to 35 feet wide

Ornamental characteristics:

- pyramidal spikes of fragrant, white flowers in mid-May

- dark purple to black cherries in August and September

- golden yellow to orange fall foliage

Landscape Use

A multi-stemmed shrubby tree, common chokecherry seems more at home in a naturalized area or in the wildlife garden than in the more cultivated landscape. It can often be found growing along fencerows, in open fields, or on the edge of the woods, often in company with native viburnums and its more tree-like and later-flowering relative, black cherry (Prunus serotina).

Chokecherry has greater shade tolerance than other native cherries, allowing it to be included in the woodland landscape where songbirds and small mammals will devour its late-summer fruit. It is also resistant to salt, drought, and heat.

Culture

Hardiness: USDA zone 2

Soil requirements: tolerant of a wide variety of soils

Light requirements: sun or part shade

Stress tolerances:

soil compaction — intolerant

pollution — intolerant

deicing salts — tolerant

urban heat islands — tolerant

drought — tolerant

seasonal flooding — intolerant

Insect and disease problems: frequent black knot

Wildlife Value

From spring through summer, chokecherry is host to over 200 species of butterflies and moths, including coral and striped hairstreaks as well as Canadian and Eastern tiger swallowtails. In winter, the cherries are eaten by some 70 bird species, including ruffed grouse, ring-necked pheasants, woodpeckers, cedar waxwings, thrushes, and grosbeaks.

Many mammals also enjoy the cherries. Bears and raccoons will climb the trees for the fruit, while foxes, chipmunks, rabbits, white-footed mice, and squirrels frequently feed on fallen fruits. Deer and moose readily browse the twigs and foliage.

Maintenance

Irrigation: During the establishment period, defined as one year after planting for each inch of trunk diameter at planting time, water your trees regularly during the growing season. Give the root zone of each tree 1 inch of water per week; in general, a tree’s root zone extends twice as wide as its canopy. After the establishment period, provide supplemental irrigation during periods of severe drought.

Fertilization: Landscape trees and shrubs should not be fertilized unless a soil test indicates a need. Correct soil pH, if necessary, by amending the backfill soil. No nitrogen fertilizer should be added at planting or during the first growing season.

To learn more about native woody plants

Visit the Eastern Maine Native Plant Arboretum at University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Penobscot County office, 307 Maine Avenue in Bangor. Established in 2004, the arboretum displays 24 different native tree and shrub species that can be used in managed landscapes.

Reviewed by Cathy Neal, Extension professor, University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension.

Photos by Reeser C. Manley.

Illustration by Margery Read, Extension Master Gardener.

This series of publications and the associated research were made possible in part by the Maine Forest Service’s Project Canopy.

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2008

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

The University of Maine System (the System) is an equal opportunity institution committed to fostering a nondiscriminatory environment and complying with all applicable nondiscrimination laws. Consistent with State and Federal law, the System does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender, gender identity or expression, ethnicity, national origin, citizenship status, familial status, ancestry, age, disability (physical or mental), genetic information, pregnancy, or veteran or military status in any aspect of its education, programs and activities, and employment. The System provides reasonable accommodations to qualified individuals with disabilities upon request. If you believe you have experienced discrimination or harassment, you are encouraged to contact the System Office of Equal Opportunity and Title IX Services at 5713 Chadbourne Hall, Room 412, Orono, ME 04469-5713, by calling 207.581.1226, or via TTY at 711 (Maine Relay System). For more information about Title IX or to file a complaint, please contact the UMS Title IX Coordinator at www.maine.edu/title-ix/.