Black Rot of Grape

Pest Management Fact Sheet #5106

Bruce A. Watt, Extension Plant Pathologist

For information about UMaine Extension programs and resources, visit extension.umaine.edu.

Find more of our publications and books at extension.umaine.edu/publications/.

Introduction

The fungus Guignardia bidwellii causes black rot of grape. It is the most common and serious disease of grape in Maine and during years when the weather is favorable losses can range up to 80% of the crop.

Symptoms

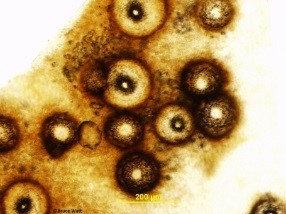

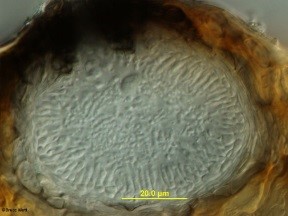

The fungus infects newly emerging leaves, fruit, canes, shoots, and tendrils. Infections are usually first noticed on the leaves where they appear as small spots which may enlarge to 1/4 inch in diameter. The spots are commonly light tan in the center and may be circled by a dark tan band (Fig.1). As the infection ages, two types of tiny, dark, spore-producing structures form within the spots (Fig.2). These superficially similar structures (Fig.3) are either spermagonia (Fig.4) or pycnidia (Fig.5) and produce spermatia (Fig.6) and conidia (Fig.7) respectively. Spots formed by infection of the shoots are larger and darker and will also produce spores.

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

Symptoms of infected fruit begin as small brownish spots that quickly expand to involve the entire fruit in a matter of days. As the infection continues, the grape shrivels from a soft brown rotted fruit to a small, black, hard mummy (Figs. 8, 9). A few, many, or most of the fruit may be infected in each cluster. Once again, spores are produced from these infected fruit.

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

Environmental Conditions

The spores that initiate infections in the spring are of two types. Ascospores are produced in pseudothecia that develop in infected, over-wintered leaves and fruit. These spores are ejected after bud-break in the spring after rain has fallen. Conidia from pycnidia in the over-wintered fruit and cane lesions (and later from new infections) are also infective. After the spores land on tissue susceptible to infection, they require sufficient time in the presence of free water in order to germinate and infect. Optimally, six hours at 80oF is sufficient for infection whereas at 50oF, 24 hours is necessary (Fig.10).

| F 50 | 55 | 60 | 65 | 70 | 75 | 80 | 85 | 90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hours 24 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 12 |

Figure 10. Hours of leaf wetness required for infection.

Spore dispersal continues through the middle of the summer and then declines until by the end of the summer no new infections occur. Through this period only new growth is susceptible to infection except for the fruit, which can be infected until the onset of color.

Management

Non-Chemical

- Fall clean up may be the most important component of a control strategy because this can remove most of the inoculum (spores) source from the planting. Rake up all leaves and fallen mummies. Be especially careful to remove mummies that remain attached to the vine and, when pruning, preferentially prune out infected canes and be careful to remove infected tendrils.

- Plant in locations that will provide plenty of sun and air circulation, and orient rows parallel to the prevailing winds (generally west-east). Provide for proper vine spacing when planting, try to maintain an open canopy, and maintain good weed control. These practices will allow for rapid drying of the plants.

- Select resistant varieties when planting

Chemical

There are two strategies for chemical control of black rot. The first strategy involves the use of protectant fungicides that must be present during infection periods to prevent infections from occurring. The second strategy relies on the ability of certain fungicides to eradicate early infections after they have occurred. All fungicides have protectant action. Protectant only fungicides include Bordeaux mix (may cause phytotoxicity), mancozeb, and ferbam. Fungicides that will move into the plant tissues (systemic) providing kickback activity include the strobilurins and the sterol inhibitors (e.g. Abound, Flint, Pristine/ Elite, Rally, Rubigan) A good general protectant schedule would be to spray at 1/2-1 inch shoot growth, immediately pre-bloom, immediately post bloom, and mid-season depending on the weather until the fruit starts to color. Care should be taken to rotate amongst chemical classes.

References

Becker, C.M. and Pearson, R.C. 1996. Black rot lesions on overwintered canes of Euvitis supply conidia of Guignardia bidwellii for primary inoculum in spring. Plant Disease 80:24-27.

Hoffman, LE et al. 2004. Integrated control of grape black rot: Influence of host phenology,Inoculum availability,sanitation , and spray timing. Phytopathology 94:641-650

NE Small Fruit Management Guide. 2013-2014.

Ramsdell,D.C. and R.D. Milholland. 1988. Black Rot. in Compendium of Grape Diseases. American Phytopathological Society, St. Paul, MN

Spotts, R.A. 1977. Effect of leaf wetness duration and temperature on the infectivity of Guignardia bidwellii on grape leaves. Phytopathology 67:1378-1381

When Using Pesticides

ALWAYS FOLLOW LABEL DIRECTIONS!

Pest Management Unit

Cooperative Extension Diagnostic and Research Laboratory

17 Godfrey Drive, Orono, ME 04473-1295

1.800.287.0279 (in Maine)

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2004, 2010, 2013

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

The University of Maine is an EEO/AA employer, and does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender expression, national origin, citizenship status, age, disability, genetic information or veteran’s status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Sarah E. Harebo, Director of Equal Opportunity, 101 North Stevens Hall, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5754, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).