University of Maine Cooperative Extension Annual Report, 2015

2015 University of Maine Cooperative Extension Annual Report

Putting university research to work in homes, businesses, farms, and communities for over 100 years.

Features highlights of recent accomplishments and the difference we make in the lives of Maine citizens and their communities.

Photos by Edwin Remsberg, unless otherwise noted.

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Merit Review Process

- Stakeholder Input

- Planned Program: The Maine Food System

- Planned Program: Sustainable Community & Economic Development

- Program: Positive Youth Development

- Appendix 1: 2015 Integrated Programming Summary

- Appendix 2: 2015 MultiState Programming Summary

- 2015 University of Maine Cooperative Extension Annual Report (PDF)

Executive Summary

The University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s ongoing focus areas continue to be the Maine Food System through research and outreach related to agriculture, aquaculture, food processing, distribution, business education, food safety, and human nutrition; and Youth Development through 4-H programs with a focus on the STEM disciplines. These programs are well supported in a variety of ways by a planned program focused in Sustainable Community and Economic Development.

Maine Food and Agriculture Center; an Integrated Partnership

In 2015 the Chancellor of the University of Maine System and the Board of Trustees expanded the Maine Agriculture Center (A partnership of the Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension) to become an expanded center called the Maine Food and Agriculture Center. Located on the University of Maine campus in Orono, the center will utilize the 16-county reach of Cooperative Extension and be led by the Executive Director of UMaine Extension. With 8,200 farms and $3.9 billion in overall economic impact, agriculture is one of Maine’s largest, fastest growing, and most promising industries. The Maine Food and Agriculture Center will encompass all sectors of the burgeoning food economy;

establish first-contact access to the programs and expertise available at all seven of Maine’s public universities; and explore opportunities for cross-campus and cross-discipline coordination and program development based on emerging needs in Maine’s food economy.

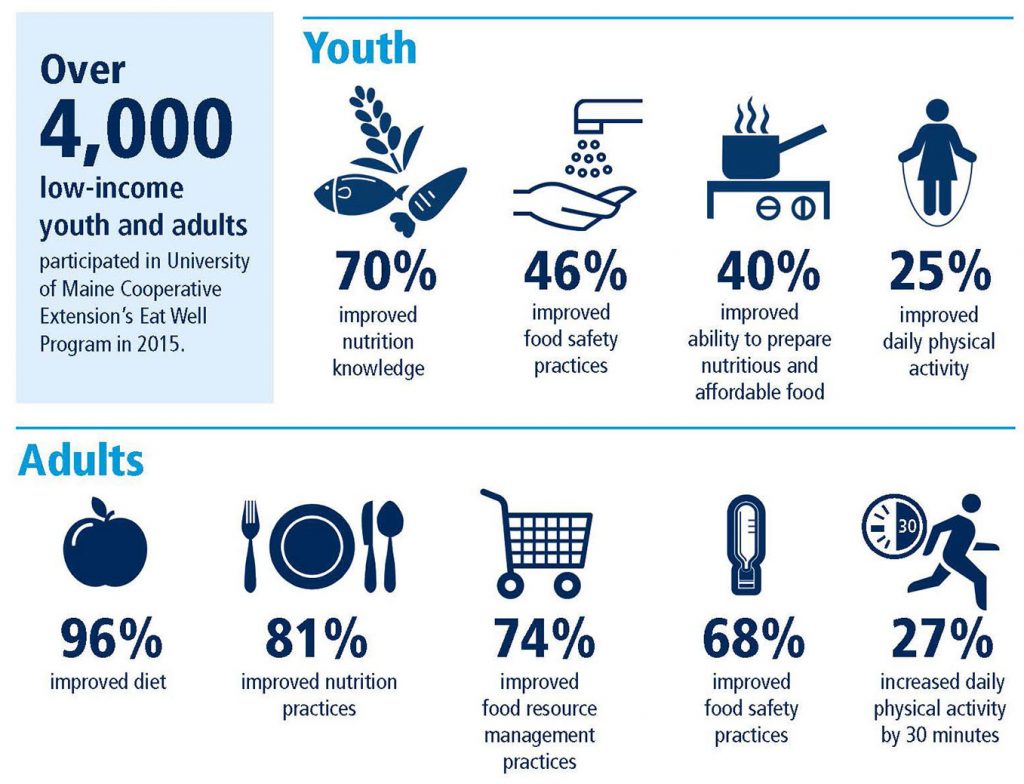

Food and Health

UMaine Extension offers a diverse portfolio of educational opportunities in the area of Food and Health to meet the needs of Maine people. Through the Eat Well Nutrition Education program, Maine FoodCorps, Home Food Preservation, Cooking for Crowds, and Dining with Diabetes programs, almost 20,000 adults and youth participated in educational opportunities last year. In Maine, 14.1 percent of the population lives in poverty, and the USDA estimates Maine’s food insecurity rate at 16.2 percent of the population, with one in four children experiencing food insecurity. UMaine Extension’s Eat Well program and Maine FoodCorps work directly with Maine’s limited income populations. Over 500 adults and 15,000 youth participated in the Eat Well Program; adult graduates reported improving their diet by increasing fruit, vegetable and whole grain intake after the program, as well as saving money on their monthly grocery expenses through planning meals and using smart shopping strategies; Eat Well youth reported improvements in choosing foods from MyPlate, food safety practices, and increased physical activity after participating in the program. FoodCorps Service Members have worked to increase the number of school gardens, and increased demand for local foods in schools, and worked directly with local food producers to connect them with local producers and growers.

UMaine Extension offers a diverse portfolio of educational opportunities in the area of Food and Health to meet the needs of Maine people. Through the Eat Well Nutrition Education program, Maine FoodCorps, Home Food Preservation, Cooking for Crowds, and Dining with Diabetes programs, almost 20,000 adults and youth participated in educational opportunities last year. In Maine, 14.1 percent of the population lives in poverty, and the USDA estimates Maine’s food insecurity rate at 16.2 percent of the population, with one in four children experiencing food insecurity. UMaine Extension’s Eat Well program and Maine FoodCorps work directly with Maine’s limited income populations. Over 500 adults and 15,000 youth participated in the Eat Well Program; adult graduates reported improving their diet by increasing fruit, vegetable and whole grain intake after the program, as well as saving money on their monthly grocery expenses through planning meals and using smart shopping strategies; Eat Well youth reported improvements in choosing foods from MyPlate, food safety practices, and increased physical activity after participating in the program. FoodCorps Service Members have worked to increase the number of school gardens, and increased demand for local foods in schools, and worked directly with local food producers to connect them with local producers and growers.

The demand for food preservation education has been growing as the public’s interest in the local food system and home gardening continues to increase. UMaine Extension remains the go-to resource for up-to-date food safety information and Master Food Preserver volunteers help to meet the public’s demand for these recommendations. Our staff and volunteers delivered more than 100 workshops, demonstrations, and displays to approximately 3,800 people. As a result participants reported understanding how to preserve foods better and feel more confident about their food preservation skills.

Food safety education is vital to keeping the Maine population safe and healthy. In an effort to provide the safest food possible to the almost 200,000 people in Maine who rely on food pantries and meal service programs to feed themselves and their families, UMaine Extension provides Cooking for Crowds: Food Safety Training for Volunteers to teach best practices and to improve food safety and reduce the risk of foodborne illness. A majority of the population served by the volunteers are food insecure families who rely on hot meals or food donations from local emergency food providers. Each volunteer in the Cooking for Crowds program has been educated on how to safely plan and purchase foods, transport and store foods, prepare foods, and how to handle left over foods to prevent food borne illnesses. The fifteen Cooking for Crowds workshops last year have provided education for 195 volunteer attendees from 9 different Maine counties, each responsible for safely feeding approximately 500 people each week (97,500 meals/week). These trained volunteers have increased their knowledge base to reduce food borne illness of the 5 million meals they serve annually to Maine’s food insecure population.

Agriculture; Extension and Research Add Value to a Key Element of Maine’s Economy

Even though Maine is 90 percent forested, the state has over 8,150 farms, the largest number of any New England state. Maine agriculture is diverse with important sectors that include wild blueberries, potatoes, dairy, livestock, poultry, grains, maple, fruits, vegetables and a vibrant ornamental horticulture industry. The University of Maine Cooperative Extension played pivotal roles in supporting a majority of these farms over the past year.

Maine’s wild blueberry industry with 500 growers added value to the 100-million-pound crop grown on 44,000 acres in 2015. UMaine Extension and Research efforts improved crop productively and efficiency by addressing pollinator population enhancement, weeds, pest insects, and diseases. The research-based knowledge provided to growers has enabled growers in Maine to remain competitive in the world marketplace and maintain a significant contribution to the State’s economy.

The Maine potato industry encompasses over 500 businesses generating over $300 million in annual sales, employing over 2,600 people and providing over $112 million in income to Maine citizens. The economic impact from our pest monitoring and educational programs for the 2015 season is estimated to be more than $11.4 million.

According to USDA statistics, there are 2,700 acres of apple orchard in Maine, with a crop value of up to $15 million per year. It is estimated that 80 apple farms in Maine produce 900,000 bushels of apples annually. UMaine Extension specialists, technicians, and scientists supported these commercial growers by addressing pest management, orchard establishment practices, variety and rootstock selection, crop load management, pruning practices, improved fruit quality and consistency, as well as harvest and storage practices that prevent losses to chilling injury and quality loss. Our Tree Fruit Integrated Pest Management Program served apple growers across the state. Extension’s Ag-Radar website provided weather-based forecasting and management timing guides for all the key apple pests. A scouting co-operative funded in part by the Maine State Pomological Society and operated by our apple IPM Program visited 25 Maine orchards weekly during the 2015 growing season. In a grower survey, savings on pesticide costs attributed to the IPM information was $207 per acre, with estimated crop damage reduction of 37 percent. Extrapolated statewide, those values become $560,000 in pesticide cost savings and over $5 million in crop value.

UMaine Extension’s Ornamental Horticulture Specialist consulted with more than 160 nursery and greenhouse businesses over the past year on plant selection, crop production, problem management, and marketing issues. As a result of these consultations, these businesses selected plants that perform well in Maine, scouted and treated pests and diseases in a way that managed them with lowest-danger/least environment-impactful methods and sold profitable crops based on cost accounting and business-sustainable models.

Food Insecurity Activities and Education

The second Maine Hunger Dialogue was held at the University of Maine this year, with 150 students and staff from 19 universities and colleges statewide. The goal of the Maine Hunger Dialogue is to inspire students to take action to address hunger on their campuses and in their communities. To help in that effort, Hunger Dialogue campus teams can apply for as much as $500 in startup funds to implement a new project, or expand/strengthen/build sustainability for an already existing hunger-related project. Projects could include activities such as establishing a new campus food pantry, hosting community “wellness” meals, establishing a resource hub, or expansion of an organic garden to provide larger quantities of fresh vegetables for local homeless shelters. As a sign of their commitment, Dialogue participants packaged 10,000 nutritious, nonperishable meals for distribution to food pantries across Maine.

The Maine Hunger Dialogue grew out of our Maine Harvest for Hunger (MHH) program. Since MHH’s inception, participants have distributed more than 2.19 million pounds of food to people in Maine experiencing food insecurity. In 2015, record-breaking donations of over 318,000 pounds of food went to 188 distribution sites and directly to individuals. Nearly 500 program volunteers in 14 counties collectively logged more than 5,000 hours. The value of the produce was over $537,000, based on an average $1.69 per pound.

4-H Youth Development in Maine

Last year more than 17,300 youth participated in the Maine 4-H program by attending 4-H camps and learning centers, 4-H community clubs, and after school and/or school enrichment programs. UMaine Extension’s 4-H youth development program is the largest out-of-school educational program in Maine. 4-H STEM Ambassadors are students at one of the University of Maine System campuses who are trained in experiential learning, risk management, and science content, who are paired with host sites to facilitate STEM activities with youth. 4-H youth development staff have been working with other campuses in the University of Maine System to expand the STEM Ambassadors’ program throughout the state. Currently, six UMS campuses are partners in this program to bring hands-on STEM education to young people in their community. In 2015, UMaine Extension trained and mentored 85 students who provided hands-on STEM learning for more than 1,000 youth; attended six University of Maine System campuses; and volunteered in 28 Maine communities.

Cooperative Extension and the Marine Extension Team

UMaine Extension has recommitted to our Marine Extension Team (MET) recently through a new memorandum of understanding with the Maine Sea Grant program. Our 16-year partnership has focused on economic outreach to address the truly unique issues of coastal communities in Maine. Our partnership supports the MET as shared staff members with expertise in community development, aquaculture, fisheries issues, climate change, coastal water quality, and tourism.

This year the MET worked with NOAA economists to develop an economic model and community-based resources to address fishing community dependence on the declining lobster fishery. Feedback from Maine pilot testers provided NOAA with specific information on the utility of the model in its current form and facilitated direct cooperation between Maine coastal community leaders and the NOAA economists to identify means to improve the model for use in Maine. The model is being revised and will be further tested in Maine.

Working waterfronts are cornerstones of many coastal communities across the country. In Maine in particular, the social, economic, and environmental value of working waterfronts is critical to the sustainability of small fishing communities. To address the need to preserve working waterfronts in Maine and the nation, the National Working Waterfront Network (NWWN) was established with the support of Maine Sea Grant leadership. The NWWN has become an important resource organization for state and federal legislators seeking to develop policy approaches to address working waterfront issues. Maine Congresswoman Pingree worked with NWWN to draft legislation entitled “Keep America’s Waterfronts Working Act of 2011,” and evolving policy effort.

Support for Maine’s Aquaculture and Marine Economy

Aquaculture continues to be one of Maine’s fastest growing industries, worth over $75 million. Much of this income is due to the net pen salmon industry. Other growing sectors of the marine economy include the shellfish industry, seaweed, baitfish and other finfish. The lobster industry in Maine, earning $365 million in 2013, is considered second only to Alaska’s in profitability, and thousands of Maine jobs are associated with lobster harvesting. Our research in the areas of sea lice of salmon, lobster health, and vaccine testing for commercial interests contributes to the health of aquaculture and aquatic animal industries in the Northeast. Contributions to knowledge about infectious salmon anemia and other salmon health issues improves aquaculture industries in other countries. Our ability to address aquaculture and fisheries issues and to engage in research will be significantly expanded with the construction of Cooperative Extension’s Plant, Animal, and Insect Diagnostic Lab.

Plant, Animal, and Insect Diagnostic Lab

Design and pre-construction work is underway for the new Cooperative Extension Plant, Animal, and Insect Diagnostic Lab. This state-of-the-art facility is a result of an $8.0 million dollar bond voted for by the people of Maine in 2014, and will support the agriculture and food based economy in Maine, and much more. The facility will house our new Maine Tick Lab, which will identify tick species and diagnose them as carriers of infectious diseases such as Lyme. We anticipate opening the lab in summer of 2017.

Extending Our Reach; Indirect Contacts

UMaine Extension extended its outreach in 2015 to over 2.1 million online visitors through its website at extension.umaine.edu. The site, a composite of 60+ interconnected websites, received more than 2.7 million page views from users in 225 countries. UMaine Extension instructional videos have been viewed more than 4,000,000 times!

Extension Volunteers

Volunteers are the heart of UMaine Extension, giving their valuable time, effort, and expertise to greatly magnify the value of our work to the people of Maine. All of our volunteers commit time to appropriate training prior to their service. As we summarize the annual reports of our faculty and staff, we are delighted to note that over 4,000 Maine people volunteered more than 85,000 hours with us this year in a myriad of ways from 4-H clubs to fundraising, from growing food to managing County budgets. This remarkable effort equates to 41 full-time staff members.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Merit Review Process

External University Panel and External Non-University Panel

In an ongoing effort to maintain valuable and relevant programming, faculty and staff engaged in formal and informal review by discipline-specific review panels and advisory groups that help to provide focus. While this results in defined programming intentions for the near- and long-term, the process is dynamic and ongoing throughout the year, and can result in new work to address emerging issues at any time.

Programming merit and success for faculty members is also reviewed by faculty peers and supervisors through reappointment, promotion, and post-tenure processes established by the faculty and administration and codified in employment contracts. A unique process exists for non-faculty programming professionals who undergo annual reviews by supervisors, and peer reviews every 4 years.

We partner with regional Extension programs in the Northeast Extension Consortium whose active vision is to coordinate translational research, education, outreach, and diversity programming to address problems, opportunities, and work force development in the Northeast region. Our primary mission is to enhance regional cooperation and improve coordination of regional Extension program initiatives for our region. Consortium partners are:

University of Connecticut

Cornell University

University of Delaware

Delaware State University

University of District of Columbia

University of New Hampshire

University of Maine

University of Maryland

Maryland Eastern Shore

University of Massachusetts

Penn State University

University of Rhode Island

University of Vermont

Rutgers University

West Virginia University

West Virginia State University

UMaine Extension is a member of the New England Planning and Reporting

Consortium, a formalized partnership of Extension programs in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont. Working in collaboration with three other states in developing and managing an online planning and reporting system results in ongoing discussions around state and regional priorities and programs, opportunities for multistate work, sharing staff resources, and a much better understanding of how each of our programs are unique from others in New England.

As a result, the four states provide periodic informal merit review and feedback as a component of our partnership. Every faculty and programming professional has online access to review the programming intentions and accomplishments of staff from other states, as does the public and important stakeholders. This capacity allows for collaborative planning, evaluation, and feedback that can communicate the value of multistate accomplishments.

- Internal University Panel

- External University Panel

- External Non-University Panel

- Combined Internal and External University Panel

- Combined Internal and External University and External Non-University Panel

- Expert Peer Review

- Other

Stakeholder Input

Actions taken to seek stakeholder input that encouraged their participation:

- Targeted invitation to traditional stakeholder groups

- Targeted invitation to traditional stakeholder individuals

- Targeted invitation to non-traditional stakeholder groups

- Targeted invitation to traditional stakeholder individuals

- Targeted invitation to selected individuals from general public

- Survey of traditional stakeholder groups

- Survey of traditional stakeholder individuals

- Other: Research using relevant current and first-source data

The University of Maine Cooperative Extension has learned from our constituents that high-quality engagement takes place best when the issue is current, and have therefore chosen to engage with stakeholders on an ongoing basis as needs and issues arise. Our matrix of County-based programs involves citizen and volunteer advisory group input as an inherent part of the work, and our statewide staff works closely with community, commodity, and professional stakeholders to guide their work. Selected examples include:

- Our partnership with County-based citizen executive committees who provide direction and advice to each local Extension programin Maine and help to prioritize regional programming efforts.

- Quarterly interactions with the UMaine Board of Agriculture, a diverse stakeholder group grounded in state legislation, advises UMaine on agricultural research and Extension priorities. The Wild Blueberry Commission of Maine who represents the industry growers and processors, and who administers a state tax fund of over $1 million.

- The Maine Potato Board composed principally of Maine-based potato farmers who offer input and advice backed up with support for research through their education and research committees. The Board also administers a state tax fund. Potatoes are Maine’s most valuable commodity.

- The Maine 4-H Foundation and its volunteer governing board who work as a close partner to enrich youth experiences through our 4-H Youth Development Program.

- A variety of advisory boards and councils who are formed with targeted intent to guide the work of some of our important programs. Examples include the Senior Companion Advisory Board, the Maine Sea Grant Policy Advisory Committee.

- Tanglewood 4-H Camp and Learning Center Board, and the Maine Board of Pesticides Control.

- We also work in partnership with discipline specific groups whose mission is to help achieve success in a given area or for a given group. Examples include the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association, Maine Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) Collaborative, Maine Math and Science Alliance, and the Sportsman’s Alliance of Maine.

- We maintain an ongoing open dialogue with Maine Legislators and county Commissioners to communicate our program focus areas and to respond to the needs that have been identified through their constituents.

Method to identify individuals and groups:

- Use Advisory Committees

- Needs assessments

- User Surveys

- Other: Identify and analyze current and emerging issues

Methods for collecting stakeholder input:

- Meeting with traditional stakeholder groups

- Survey of traditional stakeholder groups

- Meeting with traditional stakeholder individuals

- Survey of traditional stakeholder individuals

- Meeting specifically with non-traditional groups

- Other: Meetings with state government and agency leadership

How the input was considered:

- In the budget process

- To identify emerging issues

- To redirect Extension programs

- To redirect Research programs

- To set priorities

An example: A new programming direction came through our successful Maine Harvest for Hunger program that works with farmers, gardeners, and other volunteers across the state to donate surplus produce to those with limited access to fresh fruits and vegetables. The new initiative is the Maine Hunger Dialogues that mobilized national and international students and professionals from 17 Universities and many organizations to develop local and regional projects to actively address the issue of hunger.

Key Stakeholder Input Items for NIFA Attention: What did you learn from your Stakeholders?

Through our partnership with the UMaine College of Natural Sciences, Forestry, and Agriculture and the Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station, we represent the Maine Food and Agricultural Initiative, which support stakeholder-driven agricultural research and Extension education for Maine. Examples of recent projects include:

- Soil solarization for enhanced weed control in vegetables

- The use of portable doppler radar microphone to assess honey bee colony size and health

- Evaluation of Onion and Shallot Varieties for Maine Farmers

- Elderberry Virus Survey

- Testing Maine’s Wild and Cultivated Elderberries for Tomato Ringspot Virus (ToRSV)

- Improving barley quality and yields for emerging high-value markets

- Investigation and Education on the Potential Food Allergenic Residues in Composts

- Identifying Profitable Vegetable and Small Fruit Varieties for Maine (Y1-3)

Planned Program: The Maine Food System

The Maine food system is a vital component of the Maine economy. It is a complex system comprised of all aspects of food including food production, processing, distribution, consumption and even food waste. The food system provides full time, part time and seasonal employment opportunities across all sectors and contributes an estimated $3.9 billion of dollars to the Maine economy each year. Currently, the Maine food system provides approximately 20% of the food consumed in the state. However, given the land area and market potential to consumers (70 million people live within a one-day drive), there is great potential to expand the depth and breath of our food system. Extension specialists, educators and other staff provide programming using research-based information to increase the efficiency, accessibility, safety, and sustainability of all aspects of the Maine food system. We work closely with the public to improve access to healthful food; and we promote USDA’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans. We help farmers, fishermen, food processors, businesses, and individuals ensure food safety through current production, harvest and post-harvest handling and processing practices, including appropriate-scale composting to reduce the waste stream and sanitize pathogens. In addition to addressing commercial food-related efforts, Extension actively programs to improve the quality of food consumed by the general public while reducing issues of food security through the support of community and school gardens, home horticulture endeavors and the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program.

The Maine food system is a vital component of the Maine economy. It is a complex system comprised of all aspects of food including food production, processing, distribution, consumption and even food waste. The food system provides full time, part time and seasonal employment opportunities across all sectors and contributes an estimated $3.9 billion of dollars to the Maine economy each year. Currently, the Maine food system provides approximately 20% of the food consumed in the state. However, given the land area and market potential to consumers (70 million people live within a one-day drive), there is great potential to expand the depth and breath of our food system. Extension specialists, educators and other staff provide programming using research-based information to increase the efficiency, accessibility, safety, and sustainability of all aspects of the Maine food system. We work closely with the public to improve access to healthful food; and we promote USDA’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans. We help farmers, fishermen, food processors, businesses, and individuals ensure food safety through current production, harvest and post-harvest handling and processing practices, including appropriate-scale composting to reduce the waste stream and sanitize pathogens. In addition to addressing commercial food-related efforts, Extension actively programs to improve the quality of food consumed by the general public while reducing issues of food security through the support of community and school gardens, home horticulture endeavors and the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program.

Planned Program: Activities and Participation

- Crop Production Activities — Direct (Club, Conference, Program, Consultation, Scholarship, or Training)

- Crop Production Activities — Indirect (Applied Research, Media, Internet, Publication, Resulting from Training)

- Eat Well (Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program) — Indirect (Applied Research, Media, Internet, Publication,

Resulting from Training) - Eat Well (Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program) Direct (Club, Conference, Program, Consultation,

Scholarship, or Training) - Food Safety — Direct (Club, Conference, Program, Consultation, Scholarship, or Training)

- Food Safety — Indirect (Applied Research, Media, Internet, Publication, Resulting from Training)

- General Activities in Support of the Maine Food System – Direct (Club, Conference, Program, Consultation,

Scholarship, or Training) - General Activities in Support of the Maine Food System – Indirect (Applied Research, Media, Internet, Publication,

Resulting from Training) - Home Horticulture Activities — Indirect (Applied Research, Media, Internet, Publication, Resulting from Training)

- Home Horticulture Activities — Direct (Club, Conference, Program, Consultation, Scholarship, or Training)

- Livestock Activities — Direct (Club, Conference, Program, Consultation, Scholarship, or Training)

- Livestock Activities — Indirect (Applied Research, Media, Internet, Publication, Resulting from Training)

- Nutrition Education — Direct (Club, Conference, Program, Consultation, Scholarship, or Training)

- Specialty Food Products — Direct (Club, Conference, Program, Consultation, Scholarship, or Training)

- Specialty Food Products — Indirect (Applied Research, Media, Internet, Publication, Resulting from Training)

Target Audience

- 4-H Volunteers (Adult)

- 4-H Youth (Youth)

- Agricultural Producers (Adult)

- Agricultural Service Providers

- Agricultural Workers (Adult)

- Apple Growers (Adult)

- Blueberry Growers (Adult)

- Business Assist Organization Staff (Adult)

- Commercial Fishermen (Adult)

- Community Leaders (Adult)

- County Executive Committee Members (Adult)

- Cranberry Growers (Adult)

- Dairy Producers (Adult)

- Disabled Adults (Adult)

- Eat Well Participants (Adult)

- Eat Well Participants (Youth)

- Eat Well Volunteers (Adult)

- Elders or Seniors (Adult)

- Families (Adult)

- Families (Youth)

- Food Stamp Recipients (Adult)

- Forestland Owner (Adult)

- General Public (Adult)

- General Public (Youth)

- Home Gardeners (Adult)

- Home Gardeners (Youth)

- Maple Producers (Adult)

- Master Gardener Volunteers (Adult)

- Ornamental Horticulture Industry (Adult)

- Parent Educators (Adult)

- Parents (Adult)

- Pesticide Applicators (Adult)

- Potato Growers (Adult)

- Resource Managers and Scientists (Adult)

- Small or Home-Based Business Owners — Current (Adult)

- Small or Home-Based Business Owners — Potential (Adult)

- Sweet Corn Growers (Adult)

- Teachers (Adult)

- Vegetable Growers (Adult)

- Veterinarians (Adult)

- Volunteers (Adult)

|

—

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Selected Program Accomplishments – Impact Statements

AgrAbility…Supporting Farmers of All Abilities to Remain Active on the Farm

Relevance — The average U.S. farmer is 57 years old, and farming is the seventh most dangerous job in America. An estimated 5,700 farmers, farm family members, or farm workers in Maine have a chronic health condition or disability, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury, or aging-related issues, such as arthritis or hearing loss. Fishermen, forest workers, and migrant workers, a new focus of the Maine AgrAbility Project, face similar challenges for remaining productive.

Relevance — The average U.S. farmer is 57 years old, and farming is the seventh most dangerous job in America. An estimated 5,700 farmers, farm family members, or farm workers in Maine have a chronic health condition or disability, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury, or aging-related issues, such as arthritis or hearing loss. Fishermen, forest workers, and migrant workers, a new focus of the Maine AgrAbility Project, face similar challenges for remaining productive.

Response — Maine AgrAbility helps Maine farmers facing physical or cognitive challenges to enhance their ability to farm and live independently, which improves their quality of life and economic sustainability. AgrAbility specialists assess issues and offer adaptive recommendations. They provide education about safe work methods and connect people with other resources through this nonprofit partnership between the UMaine Cooperative Extension, Goodwill Industries of Northern New England, and Alpha One.

Results — Since the project began in 2010, AgrAbility has provided technical information to 247 farmers and conducted on-site assessments for 75 others with cow and goat dairies, livestock operations, Christmas tree farms, fruit orchards, agritourism, vegetable stands, maple production, and hay sales.

Clients reported increased knowledge of their conditions and increased accessibility for their daily work. They reported ways that the assessment and suggested changes helped them decrease physical pain, stress, and strain through modifications to equipment, the work or home environment, and farm operations or chores.

One participant shared this success story: “How much has this program increased my income? The new part of my business has added probably 30% to my bottom line. This new part can give me additional income even if crops fail. I just want to keep working. I don’t want to be on disability; I’m not ready for that. They are giving me tools to be successful.”

Outcome Measure: Engage positively in their community

601 Economics of Agricultural Production and Farm Management

Integrated Pest Management Strategy for Maine’s Wild Blueberry Industry Saves $12.5 Million

Relevance — A sustainable approach is needed to managing spotted wing drosophila (SWD) in wild blueberries. This invasive insect was first reported in Maine in fall 2011. In 2012 the Maine wild blueberry industry was devastated, with approximately 25% crop loss. Despite repeated warnings and emergency trainings, many growers undertook intensive and sometimes unnecessary insecticide applications, a practice that became widespread throughout the wild blueberry-growing region.

Relevance — A sustainable approach is needed to managing spotted wing drosophila (SWD) in wild blueberries. This invasive insect was first reported in Maine in fall 2011. In 2012 the Maine wild blueberry industry was devastated, with approximately 25% crop loss. Despite repeated warnings and emergency trainings, many growers undertook intensive and sometimes unnecessary insecticide applications, a practice that became widespread throughout the wild blueberry-growing region.

Response — The University of Maine Cooperative Extension has conducted extensive research and developed an integrated pest management strategy for SWD. This strategy involved training growers to identify the insect, developing a monitoring trap, developing an action threshold based on male fly captures, screening insecticides to determine the best options, integrating natural enemies of SWD with other control tactics, and demonstrating the effectiveness of exclosure netting to protect organic blueberries.

Results — The development and adoption of the Maine wild blueberry SWD strategy led to reduced insecticide spraying and almost no recorded damage, except in a few later-harvested fields. The economic impact can be assessed as reduced crop loss, which is estimated for 2015 at close to 0%, or a savings of 25% of 80 million pounds, with a processor cost of $0.60/pound, for a total of $12 million. This figure does not include savings on insecticides, the costs of their application, or benefits to the environment from reduced applications. SWD continues to be a significant problem in Maine blueberries, but growers are learning to manage this devastating pest.

Outcome Measure: Adopt and maintain integrated pest management strategies

216 Integrated Pest Management Strategies

212 Pathogens and Nematodes Affecting Plants

213 Weeds Affecting Plants

215 Biological Control of Pests Affecting Plants

211 Insects, Mites, and Other Arthropods Affecting Plants

Supporting Maine’s Wild Blueberry Industry by Controlling a Pathogenic Fungus

Relevance — Mummy berry, a serious disease caused by a pathogenic fungus, can decrease yield up to 80% in wild blueberries if not properly controlled. Maine blueberry growers were applying fungicides following a calendar method and at times when the fungicides were not effective, so growers were not successfully controlling this disease.

Response — Since 2007 UMaine has presented information to growers about a forecasting system for mummy berry. This system uses the development of the plant and fungus and weather data to determine infection. In 2015, UMaine set up 15 Internet-connected weather stations throughout the wild blueberry growing regions. We provide growers with reports on infection risk during mummy berry season and make recommendations on effective times for fungicide applications.

Results — Since starting to educate growers about the forecasting system in 2007, there has been an increase in growers using the system to determine when to apply fungicides. In 2014, approximately 67% of the growers surveyed were using the forecast system and reported improved control of mummy berry disease. Growers report using fewer fungicide applications to control this disease, and because they are applying fungicides at the proper time, they are achieving improved control. Growers using the forecasting system are saving approximately $50/acre in fungicide costs each time they avoid a fungicide application to control mummy berry. Statewide, a total of $590,000 is saved if all growers using the forecast system reduce fungicide use by one application. This figure does not include benefits to the environment from reduced fungicide applications and the increased yield from effectively controlling this disease.

Outcome Measure: Identify pest problems and determine research-based management strategies.

212 Pathogens and Nematodes Affecting Plants

216 Integrated Pest Management Systems

Cooking for Crowds and Keeping It Safe

Relevance — According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), 2011 estimates indicate that 1 in 6 people (48 million) in the United States become sick from contaminated food each year, resulting in 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths. Problems can arise from cross-contamination, improper holding time of food, and poor hygiene during food preparation.

Relevance — According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), 2011 estimates indicate that 1 in 6 people (48 million) in the United States become sick from contaminated food each year, resulting in 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths. Problems can arise from cross-contamination, improper holding time of food, and poor hygiene during food preparation.

Response — To provide the safest food possible to the 178,000 Mainers annually who rely on food pantries and meal service programs, UMaine Extension provides Cooking for Crowds: Food Safety Training for Volunteers to teach best practices that improve food safety and reduce the risk of foodborne illness. Each volunteer in the program has been educated on how to safely purchase, transport, store, and prepare foods, and handle leftover foods to prevent foodborne illnesses.

Results — The fifteen Cooking for Crowds workshops in this program year have educated 195 volunteer attendees from nine Maine counties. Each of the attendees is responsible for safely feeding approximately 500 people/week (97,500 meals/week). These trained volunteers have increased their knowledge base to reduce foodborne illness from the 5 million meals they serve annually to Maine’s food-insecure population.

A 2014 USDA-ERS study estimated the costs of illnesses caused by 15 major foodborne pathogens at more than $15.6 billion/year in the U.S. Using the CDC numbers above, and assuming that foodborne illness patterns mirror population patterns and that the Cooking for Crowds program reduces foodborne illness in Maine by even just 1%, the program would prevent more than $640,000 in economic losses and 1,977 cases of foodborne illness annually.

Outcome Measure: Adopt specific food safety plans and/or policies

702 Requirements and Function of Nutrients and Other Food Components

502 New and Improved Food Products

Protecting Maine’s Dairies

Relevance — Many of Maine’s more than 8,000 small farms have dairy animals. Increasingly, organic and small ruminant dairies are producing a diverse collection of artisanal cheeses and alternative milk products. For public safety and quality control, dairies must keep pathogenic bacteria out of their dairy animals and dairy products. Culturing milk samples (bulk tank or individual animal samples) is key to protecting Maine’s dairies, both large and small.

Relevance — Many of Maine’s more than 8,000 small farms have dairy animals. Increasingly, organic and small ruminant dairies are producing a diverse collection of artisanal cheeses and alternative milk products. For public safety and quality control, dairies must keep pathogenic bacteria out of their dairy animals and dairy products. Culturing milk samples (bulk tank or individual animal samples) is key to protecting Maine’s dairies, both large and small.

Response — In 2014-2015, the UMaine Animal Health Lab cultured approximately 2,000 milk samples for mastitis; 4.5 percent were positive for Staphylococcus aureus, one of various pathogens causing infected udders in cattle. Unlike many mastitis-causing pathogens, S. aureus can cause serious human illness. Because S. aureus cannot usually be cleared from the udder, culling chronically infected cows is advised to protect the public and avoid the spread of this disease on dairies.

Results — Maine’s dairy owners and dairy product consumers continue to benefit from our local, responsive mastitis diagnostic service. We screen samples from both large and small dairies for mycoplasma, S. aureus, and other pathogens. Allowing farmers to administer antibiotics appropriately, and to avoid excessive antibiotic use by culling animals with incurable infections, saves money and protects public health. Effective responses to animal illnesses are possible only when the disease is identified. Involvement with a multistate project, Mastitis Research Workers, has resulted in grant proposals regarding milk quality assessment and improvement.

Outcome Measure: Improve animal health and well-being

501 New and Improved Food Processing Technologies

301 Reproductive Performance of Animals

302 Nutrient Utilization in Animals

311 Animal Diseases

Fostering the Next Generation of Organic Dairy Farmers

Relevance — The average age of dairy farmers in Maine is approaching 60 years. Too few young people are entering the field of organic dairy. Labor costs are one of Maine dairy farms’ largest expenses. Maine ranks very low in number of cows per full-time equivalent worker. Meanwhile, the demand for organic milk is increasing at a dramatic rate, creating a shortage of organic milk and a significant price premium.

Relevance — The average age of dairy farmers in Maine is approaching 60 years. Too few young people are entering the field of organic dairy. Labor costs are one of Maine dairy farms’ largest expenses. Maine ranks very low in number of cows per full-time equivalent worker. Meanwhile, the demand for organic milk is increasing at a dramatic rate, creating a shortage of organic milk and a significant price premium.

Response — UMaine Extension helped Wolfe’s Neck Farm develop and launch a residential Organic Dairy Farmer Research and Training Program that aims to increase production of organic milk in the Northeast. The program partners with new, transitioning, and existing organic dairy farmers to improve practices and ensure long-term sustainability and production in this region. This program, the first of its kind in the nation, is funded with a $1.7 million grant from Danone Ecosystem Fund and Stonyfield Yogurt.

Results — Wolfe’s Neck Farm operators have started the training program with three trainees and a milking system imported from the Netherlands. Since 2014 more than a dozen farms have made or started the switch from conventional to organic production, with three processors vying for producers. If we assume that these twelve producers represent an increase of nearly 20% in the number of commercial organic dairy farms in the state, that increase would represent a value of $327,600 to Maine farmers.

Extension faculty member Rick Kersbergen has been an invited speaker at several regional dairy meetings to talk about robotic milking and innovative technology. His blog, Cows and Crops, received 1,540 page views from Oct 1, 2014, to February 2015. He spent part of his recent sabbatical in the Netherlands and Germany learning about their equipment and facilities innovations that he might bring back to Wolfe’s Neck Farm and other Maine organic dairies.

Outcome Measure:

601 Economics of Agricultural Production and Farm Management

Eat Well: Responding to Food Insecurity

Relevance — More than 13 percent of Mainers (180,892 people) live in poverty. Food insecurity in the state has increased dramatically in the past 10 years to 15.5 percent (206,090 people) of the Maine population. With food insecurity comes greater health risks. Overweight, obesity, sedentary lifestyles, and poor diet quality are associated with many chronic diseases. In Maine, almost two-thirds of adults and more than a quarter of school-aged youth are overweight or obese.

Relevance — More than 13 percent of Mainers (180,892 people) live in poverty. Food insecurity in the state has increased dramatically in the past 10 years to 15.5 percent (206,090 people) of the Maine population. With food insecurity comes greater health risks. Overweight, obesity, sedentary lifestyles, and poor diet quality are associated with many chronic diseases. In Maine, almost two-thirds of adults and more than a quarter of school-aged youth are overweight or obese.

Response — Maine Cooperative Extension’s EFNEP paraprofessionals educate Maine’s limited-income families and youth to help them make better lifestyle choices and improve their nutritional well-being. EFNEP participants learn how to eat well on a budget and apply what they learn in their daily lives. These positive changes will eventually help reduce the incidence of obesity and chronic disease of limited income families in Maine.

Results — As a result of completing the Eat Well program funded by EFNEP (320 adult participants surveyed):

- 74 percent (237) showed improvement in one or more food resource management practice (i.e., plans meals, compares prices, does not run out of food, uses grocery lists).

- 81 percent (258) showed improvement in one or more nutrition practice (i.e., plans meals, makes healthy food choices, prepares food without adding salt, reads nutrition labels, or has children eat breakfast).

- 68 percent (218) showed improvement in one or more food safety practice (i.e., thawing and storing foods correctly).

Eat Well graduates reported increasing fruit and vegetable intake by one-half cup per day and self-reported increases in fiber, calcium, and vitamin D intake. Fifteen percent of Eat Well graduates also reported increasing physical activity to at least 30 minutes per day.

Outcome Measure: Increase consumption and preservation of healthful, locally-grown and -produced food (farm to school program, food preservation, etc.)

704 Nutrition and Hunger in the Population

702 Requirements and Function of Nutrients and Other Food Components

703 Nutrition Education and Behavior

The “Whole Schools Whole Communities” Initiative

Relevance — Research shows that when students in grades 6-12 are provided meaningful opportunities to connect academic work to real world issues in a supportive context of peers and adult mentors, many achieve enhanced academic and personal success. Increasingly, Maine schools are challenged to find funding to support out-of-classroom activities that meet these goals. Meanwhile, schools are tasked with implementing proficiency-based curricula with deadlines as early as 2018.

Relevance — Research shows that when students in grades 6-12 are provided meaningful opportunities to connect academic work to real world issues in a supportive context of peers and adult mentors, many achieve enhanced academic and personal success. Increasingly, Maine schools are challenged to find funding to support out-of-classroom activities that meet these goals. Meanwhile, schools are tasked with implementing proficiency-based curricula with deadlines as early as 2018.

Response — The Environmental Living and Learning for Maine Students (ELLMS) Project secured a $275,000 grant to implement the Whole Schools Whole Communities Initiative. The project partners — UMaine’s 4-H centers, Chewonki, the Schoodic Institute, and the Ecology School — have joined with 10 Maine school districts to engage in a facilitated planning process designed to deepen schools’ connections with nonprofit learning centers and connect students and curricula to natural landscapes and human communities.

Results — Ten Maine public school districts representing nearly 8,000 students are deeply engaged in the process of envisioning and implementing significant change in teaching and learning. This process includes facilitated planning sessions during which school leaders, teachers, community stakeholders, and ELLMS Project representatives are collectively shaping the future of education to include meaningful connection to community through service learning opportunities, leadership development, place-based curricula, outdoor field science, and STEM. The ELLMS partners are also conducting an integrated research project using “Most Significant Change” methodology. The research is designed to ascertain the longitudinal impact of quality environmental education opportunities for students and teachers.

Outcome Measure: Youth will reduce sedentary activity

724 Healthy Lifestyle

The Farmer Veteran Coalition of Maine

Relevance — Military veterans are looking to the Maine food system for employment. Veterans are an underserved audience in Maine and often entrepreneurial, enjoy working toward goals, and doing physical labor. Farming also allows veterans to use outdoor work and interaction with livestock as therapy. The unique needs of veteran farmers led to the creation of a national nonprofit, the Farmer Veteran Coalition (FVC), in California. Veteran farmers wanted a Maine chapter, but a lack of experience in organizing formal groups impeded progress.

Relevance — Military veterans are looking to the Maine food system for employment. Veterans are an underserved audience in Maine and often entrepreneurial, enjoy working toward goals, and doing physical labor. Farming also allows veterans to use outdoor work and interaction with livestock as therapy. The unique needs of veteran farmers led to the creation of a national nonprofit, the Farmer Veteran Coalition (FVC), in California. Veteran farmers wanted a Maine chapter, but a lack of experience in organizing formal groups impeded progress.

Response — UMaine Extension led an effort to bring together stakeholders to determine the needs for military veteran farmers in Maine and to form an FVC chapter. Farmer veterans, agricultural and veterans service providers, and elected officials met regularly to assess local resources in agriculture, particularly for beginning farmers, and veterans’ benefits applicable to this group. In 2015 a board of directors was formed and the official application for a state chapter was submitted to the national FVC.

Results — Through two years of meetings, stakeholders developed a comprehensive inventory of resources available to veteran farmers, and the needs of this group became more clear to all participants. Organizing this group served as a model for how to bring together and communicate within a community group in general. The use of Robert’s Rules of Order, development of meeting agendas, the use of subcommittees to do work between meetings, consistent communication by email and Facebook, and regular attendance at in-person meetings all were important in working toward a common goal. Maine is now recognized by the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry; and is the first official FVC state chapter in the country. As a result farmer veterans have increased access to:

- a branding effort know as “Homegrown By Heroes,”

- specific educational opportunities geared towards veterans,

- shared use equipment, and

- a community of farmer veterans with whom they can share their struggles and successes.

Outcome Measure: Expand a business

601 Economics of Agricultural Production and Farm Management

Maine Food Corps: Connecting Kids to Real Food and Reducing Obesity

Relevance — In the last 30 years, the percentage of overweight or obese children in this country has tripled. According to a 2012 University of Maine study, the medical costs of obesity associated with the current cohort of Maine children and adolescents — both those who are obese and non-obese — will be an estimated $1.2 billion over the next 20 years. Increasing the percent of healthy Maine youth will significantly reduce our future healthcare spending.

Relevance — In the last 30 years, the percentage of overweight or obese children in this country has tripled. According to a 2012 University of Maine study, the medical costs of obesity associated with the current cohort of Maine children and adolescents — both those who are obese and non-obese — will be an estimated $1.2 billion over the next 20 years. Increasing the percent of healthy Maine youth will significantly reduce our future healthcare spending.

Response — UMaine Extension has acted as the host site for FoodCorps in Maine since its inaugural year in 2011. FoodCorps is a nationwide team of AmeriCorps leaders who connect kids to healthy food and help them grow up healthy. In the past 4 years, our 6-12 service members have served in 47 schools teaching 16,973 students about food and nutrition. They have coordinated the building of 15 new school gardens, made contacts with 71 local food producers, and engaged 387 new volunteers who contributed 6,869 hours of service.

Results — Survey results from a subset of youth served show 50 percent net improvement in vegetable preferences. In addition to positive changes in food preference, youth have greater access to healthy food options through school lunch offerings, taste tests, and home backpack and school pantry programs.

The FoodCorps Landscape Assessment showed improvement in school food environments in 89% of Maine schools with FoodCorps service.

Examples of observed outcomes that will result in long-term change in schools and the communities they serve as a result of FoodCorps support include more:

- demand for local fresh food in school and home meals,

- volunteer resources to support school garden and nutrition initiatives,

- knowledge of resources that UMaine Extension and other service providers can offer,

- educators trained in garden-based nutrition programming and

- food service staff requesting bids from local farms.

Our data mirrors overall national trends documented by USDA indicating farm to school success.

Outcome Measure: Youth will follow healthy eating patterns

704 Nutrition and Hunger in the Population

724 Healthy Lifestyles

Food Safety Education for Families and Commercial Food Producers

Relevance — Each year 48 million people in the United States contract foodborne illnesses. Safe food is essential to avoiding illness and staying healthy. In Maine, food safety risks exist in home food preparation and preservation, from people serving crowds, and in retail and commercial manufacturing and sales. All of these groups prepare or process food for others, but many of these potential food preparers do not have proper food safety training, leading to an increased occurrence of foodborne illness.

Relevance — Each year 48 million people in the United States contract foodborne illnesses. Safe food is essential to avoiding illness and staying healthy. In Maine, food safety risks exist in home food preparation and preservation, from people serving crowds, and in retail and commercial manufacturing and sales. All of these groups prepare or process food for others, but many of these potential food preparers do not have proper food safety training, leading to an increased occurrence of foodborne illness.

Response — UMaine Extension provides food safety training programs such as food preservation; home food safety; Cooking for Crowds; industrial food sanitation; Good Agricultural Practices; Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP) certification; and soon, Food Safety Modernization Act trainings. Extension provides private food safety consulting and process authority food

product reviews to companies statewide. These programs directly reached and trained over 10,000 people in Maine in the past year.

Results — We estimate that more than 50,000 consumers of home prepared and preserved food, and those attending public and community events, have a reduced potential to contract foodborne illness due to our food safety trainings. Further, more than 500,000 consumers of food produced by New England-based food businesses have a reduced potential to contract foodborne illness because of our trainings.

The food process authority lab reviewed over 500 products, leading to added income and jobs across Maine and New Hampshire. In almost all cases one-onone food safety consulting led to increased revenue, retention of jobs, and/or increased hiring. One new startup company hired 171 employees and said, “Extension’s work with our company has contributed to the safe production of 7.2 million pounds of lobster per year with a value of over $36 million.” These results are decreasing the occurrences of foodborne illness and increasing overall health in Maine and wherever Maine foods are sold and consumed.

Outcome Measure: Improve Food Safety

502 New and Improved Food Products

501 New and Improved Food Processing Technologies

Improving Potato Yields to Sustain Market Viability

Relevance — Potato producers in Maine need to improve potato yields to sustain market viability. The industry’s taskforce proposed lengthening rotations (increasing the time between potato crops on any field). But this strategy brings economic challenges because of greater time between potato crops, lack of crop diversity in current portfolios, and the lack of potential alternative crops, alternative markets for existing crops, and value-added processing potential for new and existing rotation crops.

Relevance — Potato producers in Maine need to improve potato yields to sustain market viability. The industry’s taskforce proposed lengthening rotations (increasing the time between potato crops on any field). But this strategy brings economic challenges because of greater time between potato crops, lack of crop diversity in current portfolios, and the lack of potential alternative crops, alternative markets for existing crops, and value-added processing potential for new and existing rotation crops.

Response — A collaborative project was undertaken between UMaine Extension and the Maine Potato Board, which since 2014 has secured $225,000 in grant money. We have emphasized rotation and alternative crop research and education. Efforts have been made to increase producers’ awareness of the biological, financial, and ecological consequences of cropping choices and systems. We have also increased awareness about geographically atypical farm revenue streams such as value-added processing and agritourism.

Results — As a result of this collaborative effort, the Maine Potato Board has a hired a full-time professional to research rotation crops and cropping alternatives and to educate its growers. We have secured funding to conduct crop market assessments and feasibility studies. To date, local farming practice changes have included increased acreages of soybeans, canola, and green manure crops. Several area growers are now experimenting with small-scale, high-value crops such as hops and grapes. One farm family has diversified into value-adding several of the farm’s rotation crops such as barley and oats, and they are now producing malt for Maine beer brewers and processed feed for New England livestock.

Outcome Measure: Implement practices that improve efficiency, reduce inputs and negative impacts on the environment, increase profitability, or reduce energy consumption.

205 Plant Management Systems

211 Insects, Mites, and Other Arthropods Affecting Plants

212 Pathogens and Nematodes Affecting Plants

213 Weeds Affecting Plants

215 Biological Control of Pests Affecting Plants

216 Integrated Pest Management Systems

501 New and Improved Food Processing Technologies

502 New and Improved Food Products

601 Economics of Agricultural Production and Farm Management

Protecting Maine’s Poultry and Egg Industry

Relevance — Maine’s poultry and egg industries are worth over $75 million yearly. Because the University of Maine Animal Health Lab (UMAHL) provides the FDA-required salmonella testing for medium- to large-sized egg producers in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, these farms can operate within FDA’s Egg Rule. This work protects public health via prevention of human salmonellosis (SE) that might be acquired through eggs.

Relevance — Maine’s poultry and egg industries are worth over $75 million yearly. Because the University of Maine Animal Health Lab (UMAHL) provides the FDA-required salmonella testing for medium- to large-sized egg producers in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, these farms can operate within FDA’s Egg Rule. This work protects public health via prevention of human salmonellosis (SE) that might be acquired through eggs.

Response — Both large and small producers may require disease diagnosis and monitoring. UMAHL handled over 6,000 avian samples during reporting year 2015. We provided national training to producers on how to manage carcass mortalities with highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) through composting. Disease prevention and diagnostic consultation also extends to meat producers.

Results — It is estimated that the cost to the egg industry of an SE outbreak could be higher than 10% of production. Although it is difficult to accurately estimate the impact of the lab, the impact of salmonella prevention alone is estimated to be more than $7 million per year.

During 2015, HPAI caused the death of more than 49 million poultry in the United States. If this disease comes to our region, substantial losses to the commercial egg industry would result. UMAHL is working with small and large producers to increase biosecurity and preparedness for emergencies such as HPAI.

Outcome Measure: Adopt specific food safety plans and/or policies in response to disease (Action)

311 Animal Diseases

403 Waste disposal, recycling, and reuse

IPM Strategies for Sweet Corn

Relevance — Sweet corn comprises nearly half of the commercial vegetable acreage in Maine, yet it may bring only marginal profits due partly to high pest management costs. Of the three major corn pests in Maine, only one can survive the winter; the other two must fly north each summer. These factors make sweet corn an ideal candidate for integrated pest management (IPM) strategies.

Relevance — Sweet corn comprises nearly half of the commercial vegetable acreage in Maine, yet it may bring only marginal profits due partly to high pest management costs. Of the three major corn pests in Maine, only one can survive the winter; the other two must fly north each summer. These factors make sweet corn an ideal candidate for integrated pest management (IPM) strategies.

Response — Farmers volunteered their fields for pest monitoring and demonstration of IPM techniques. UMaine Extension set up insect traps and trained student field scouts to regularly monitor sweet corn pest populations and report to participating farmers. Information gathered from 24 farms was summarized and shared with growers, agricultural consultants, and Extension educators around Maine through a weekly newsletter (154 recipients) and blog. Corn IPM techniques were also demonstrated at two grower field days.

Results — Growers adopting these techniques could see significant reductions in pest management costs and reduced the risk of pesticide exposure to themselves and the environment. Of the participants responding to a post-season survey, 61% used the information provided by the program to reduce the number of pesticide sprays they applied (average saved three sprays). 69% found the program significantly reduced their pest management costs (e.g., 25%), and more than 75% found that adopting IPM techniques improved their crop yield and quality. Applying the sample results to numbers from recent state agricultural statistics suggests that Maine growers conservatively reduced insecticide applications by over 100,000 gallons this season and saved over $100 per acre on insecticide costs.

Outcome Measure: Increase Profitability

205 Plant Management Systems

211 Insects, Mites, and Other Arthropods Affecting Plants

Expanding and Diversifying Maine’s Local Wheat Economy

Relevance — Recent successes in building New England’s local wheat economy have inspired new markets for various food grains. Our region now boasts scores of businesses (e.g., mills, bakeries, malt houses, and distilleries) with business models centered around locally grown grains. The need for local sources of organic and non-GMO feed grains continues to grow and is a documented bottleneck in the supply chain for organic value-added products. Local grains could become an important agricultural sector for our region.

Relevance — Recent successes in building New England’s local wheat economy have inspired new markets for various food grains. Our region now boasts scores of businesses (e.g., mills, bakeries, malt houses, and distilleries) with business models centered around locally grown grains. The need for local sources of organic and non-GMO feed grains continues to grow and is a documented bottleneck in the supply chain for organic value-added products. Local grains could become an important agricultural sector for our region.

Response — UMaine Extension initiated a comprehensive research and extension program in local food and feed grains. We secured over $1 million in grants and gifts in 2015 to fund a diverse program that generates region-specific, research-based information and provides educational and networking opportunities for participants in the grain economy. Key collaborators include MOFGA, the Maine Grain Alliance, the University of Vermont, and the US Organic Grain Collaboration.

Results — Maine and New England farmers now have access to ground-truthed information on local grain production, markets, quality standards, and economics. Research trials started in 2013 on field peas as a rotation crop for cereal grains inspired and informed at least five farmers to grow about 800 acres of field peas in 2015 for local markets. Three winter grain farmers adjusted seeding and fertility methods based on on-farm research results, affecting another 800 acres. Aroostook County farmers grew approximately 1,000 acres of organic grains—at least a five-fold increase since 2009. Two farmers planted a specialty heirloom rye for a new Nordic restaurant in New York City as a result of our connections and three years of trialing. With our guidance, a cooperating farmer produced Maine’s first crop of blue tag certified organic grain seed, and one of the region’s first certified seed of an heirloom variety. Farmers are successfully supplying new and expanding grain markets with high quality grain.

Outcome Measure: New crops and markets developed

601 Economics of Agricultural Production and Farm Management

205 Plant Management Systems

Standard Output Measures:

Direct Contacts Adult: 93,596

Indirect Contacts Adult: 1,415,883

Direct Contacts Youth: 9,361

Indirect Contacts Youth: 222

Planned Program: Sustainable Community & Economic Development

Community Development

Those who benefit from UMaine Extension’s educational initiatives in community development learn how to be effectively engaged in their communities through volunteerism, public service, becoming involved in and improving their skills with public organizations, and group process skills. This contributes to more effective public organizations, and more effective use of limited public resources as trained citizens are increasingly involved in process and decision-making.

Economic Development

Those who benefit from UMaine Extension’s educational initiatives in economic development learn how to effectively manage and sustain small and home-based businesses, household resources and community assets. This contributes to viable businesses, households, and communities that will benefit other community members by contributing to gainful employment, quality of place, and municipal tax revenues that support community services.

Planned Program: Activities and Participation

Activity (What was done?)

- Community Development — Direct (Club, Conference, Program, Consultation, Scholarship, or Training)

- Community Development — Indirect (Applied Research, Media, Internet, Publication, Resulting from Training)

- Economic Development — Direct (Club, Conference, Program, Consultation, Scholarship, or Training)

- General Community and Economic Development Activities — Direct (Club, Conference, Program, Consultation, Scholarship, or Training)

- General Community and Economic Development Activities — Indirect (Applied Research, Media, Internet, Publication, Resulting from Training)

- Small and home based business education — Direct (Club, Conference, Program, Consultation, Scholarship, or Training)

- Small and home based business education — Indirect (Applied Research, Media, Internet, Publication, Resulting from Training)

Target Audience

- 4-H Volunteers (Adult)

- 4-H Youth (Youth)

- Agricultural Producers (Adult)

- Agricultural Service Providers

- Business Assist Organization Staff (Adult)

- Organization Staff (Adult)

- Aquaculturalists (Adult)

- Commercial Fisherman (Adult)

- Community Leaders (Adult)

- County Executive Committee Members (Adult)

- Extension Staff (Adult)

- Families (Adult)

- Families (Youth)

- General Public (Adult)

- General Public (Youth)

- Home Gardeners (Adult)

- Resource Managers and Scientists (Adult)

- Small or Home-Based Business Owners — Current (Adult)

- Small or Home-Based Business Owners — Potential (Adult)

- Volunteers (Adult)

|

—

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Selected Program Accomplishments — Impact Statements

Protecting Maine’s Coastal Tourism Industry and Coastal Beaches

Relevance — Tourism and coastal beaches are integral components of Maine’s economy and way of life, yet elevated bacteria levels and other forms of pollution threaten public health and ecosystem integrity. In 2014, coastal tourism and recreation added $2.5 billion to Maine’s gross domestic product ($1.2 billion in wages; 64,943 jobs; 5,024 establishments).

Relevance — Tourism and coastal beaches are integral components of Maine’s economy and way of life, yet elevated bacteria levels and other forms of pollution threaten public health and ecosystem integrity. In 2014, coastal tourism and recreation added $2.5 billion to Maine’s gross domestic product ($1.2 billion in wages; 64,943 jobs; 5,024 establishments).

Response — UMaine Extension coordinates Maine Healthy Beaches, a quality-assured program to monitor water quality and protect public health on coastal beaches. Extension staff also build local capacity to identify, eliminate, and prevent pollution sources. This work helps protect against water-borne illnesses and protects the state’s coastal tourism. Only 16% of beach managers believe their communities would continue some form of monitoring without the program and support provided by UMaine Extension.

Results — Maine coastal residents and visitors value work that protects public health, reduces pollution, and keeps Maine’s tourism industry resilient and strong. When asked about the most important problems related to impaired water quality, 63% identified public health issues as “extremely important” and 46% noted increased beach advisories as “extremely important.” Local beach managers also believe the program delivers diverse benefits to Maine communities:

- 84% noted greater protection of public health,

- 80% noted improved beach information for residents and visitors,

- 76% noted improved beach information for local officials, and

- 67% noted improved coastal water quality.

When asked to prioritize coastal management issues, beach users ranked reducing coastal pollution first among thirteen priorities. Clean waters and sandy beaches were the two most important factors to beach users when planning visits to coastal areas.

Outcome Measure: Assess community needs and assets

608 Community Resource Planning and Development

Maine College Students Take Action on Food Security

Relevance — Increasing student retention and building strong connections with surrounding communities are two goals that all institutions of higher learning throughout Maine have in common. Food insecurity can have a direct impact on student retention. Students engaged in community service can greatly enhance the positive connections schools can have in their community. Until 2014, there was no organized effort among Maine’s college campuses to address hunger on campus and in their communities.

Relevance — Increasing student retention and building strong connections with surrounding communities are two goals that all institutions of higher learning throughout Maine have in common. Food insecurity can have a direct impact on student retention. Students engaged in community service can greatly enhance the positive connections schools can have in their community. Until 2014, there was no organized effort among Maine’s college campuses to address hunger on campus and in their communities.

Response — UMaine Extension collaborated with the Maine Campus Compact to offer the first Maine Hunger Dialogue (MHD) in 2014. We invited all Maine colleges and universities to send students and staff to learn about hunger on local, national, and global scales and to leave with ideas and action plans for ending hunger in their regions. The event was purposely designed to allow for inter- and intra-campus networking to capitalize on the diverse group convened.

Results — Representatives from 16 colleges and one high school developed new partnerships, assessed community needs and assets, and set goals and identified action steps. Six teams were awarded $500 grants to support new or existing initiatives. Teams were required to report the impacts of the grant at the 2015 MHD. Groups used the funds to obtain a refrigerator and freezer for their food pantry, develop a website for an edible park, build leverage toward establishing a campus food pantry, expand a community garden, purchase items for a resource hub, and sponsor a bake sale to raise food drive funds. One team used their new connections to start a chapter of the Food Recovery Program. They recovered over 1,500 pounds of food for a local food pantry in one semester.

Through MHD, UMaine Extension has strengthened partnerships with Maine Campus Compact, Good Shepherd Food Bank, Maine corporations, UMaine System campuses, and other Maine institutes of higher education to take action on hunger.

Outcome Measure: Strengthen human capacities, human capital, building partnerships

805 Community Institutions, Health, and Social Service

608 Community Resource Planning and Development

801 Individual and Family Resource Management

Protecting Wildlife Health

Relevance — Regional wildlife professionals have not had a local, comprehensive wildlife disease diagnostic lab system in the northeastern U.S. until recently. Maine has joined a group of laboratories that can “link” our regional agencies with local diagnostic assistance for wild animals, the Northeast Wildlife Disease Cooperative (NWDC).

Response — Collaboration with the Department of Inland Fish and Wildlife has yielded information about the health of both Maine and New Hampshire moose. We have documented health status at capture of more than 200 radio-collared moose over a 3-year period, performed surveillance of hunter-killed moose lung parasites, and provided diagnostic services for radio-collared moose dying of natural causes.

During 2014-15, the University of Maine Animal Health Lab (UMAHL) hosted wildlife biologist trainings, provided diagnostic information for wildlife cases. UMAHL assisted in investigations of lead toxicosis in waterfowl.