Made in Maine: Thoughts on Food, Animals, and Agriculture

That’s No Yolk

By Donald E. Hoenig, VMD

A couple weeks ago, my oldest daughter who lives on Cape Cod with her husband and our 18-month-old grandson, asked me if eggs needed to be refrigerated and it gave me the idea for my next blog.

A couple weeks ago, my oldest daughter who lives on Cape Cod with her husband and our 18-month-old grandson, asked me if eggs needed to be refrigerated and it gave me the idea for my next blog.

Did you know that the State of Maine is the country’s largest producer of brown eggs? Pretty amazing for such a small state but it’s true. Although our brown egg industry has shrunk somewhat in the past couple years, eggs are still 4th in farm gate value (the price paid to farmers) in the latest USDA Census of Agriculture (behind potatoes, milk and aquaculture). The town of Turner has more than 3.6 million laying hens, which lay both white and brown eggs, in complexes managed by Moark Inc., a subsidiary of Land O’ Lakes.

Why brown eggs in Maine and why do New Englanders apparently prefer brown over white eggs? This regional preference dates to the 19th century when Yankee clipper ships and whalers returning from China and the Far East brought back chickens that produced brown eggs. The Chinese prefer brown eggs to white eggs and ultimately these hens became the origin of a burgeoning egg industry in New England later in the 19th and into the 20th century.

The chickens on the Moark farm are all raised in what are referred to as battery cages. Maine Department of Agriculture standards require that no more than 4-5 birds can be kept in one cage. All birds have free access to feed and water 24 hours per day and can stand up, lie down and turn around freely. When the eggs are laid, they roll onto conveyor belts in front of the cages and are carried into the processing plant where they are washed and put in cartons without ever being touched by a human hand.

So what about some of the terms that you see on egg cartons in the grocery store now like “organic,” “cage-free,” “free-range,” and “pasture-raised”? Understanding labels can be pretty confusing so here are some explanations.

The word organic means that the eggs were laid by birds raised according to U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Organic Program standards. This means they have not been fed any antibiotics at any time in their life and that the feed they eat is also produced according to USDA organic standards, without the use of pesticides or herbicides. State inspectors or inspectors employed by third-party certifiers inspect the farms, usually annually, to assure that organic program standards are being followed. In Maine, the Maine Organic Farmers Gardeners Association (MOFGA) oversees MOFGA Certification Services, which conducts these inspections.

What about cage-free? This generally means that the chickens are not housed in cages but are kept in a building, protected from the elements, on slatted floors, with the ability to roam the building freely, eat, drink, and lay their eggs in nest boxes. The eggs are then collected automatically on conveyor belts.

Free-range is cage-free with some sort of outdoor access for the birds. Doors are opened during daylight and the birds are free to wander outside. Pasture-raised or pasture-access just means that the birds have outdoor access during daylight to an area with a substantial covering of vegetation which is rotated frequently enough to maintain the quality of that vegetation.

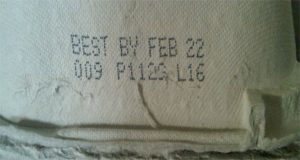

Aside from the organic standards, you might be wondering who monitors whether any of these standards are actually being followed. That’s a subject for another column, but I’ll leave you with what will probably be the most useful piece of information in this blog post. In the attached picture of the end of an egg carton, you’ll notice a series of numbers and a date. The “best by” date, Feb. 22, is 45 days from when the eggs were actually laid by the hen. Thus, a “best by” date of Feb. 22 means the eggs were laid on January 9. If it’s too confusing to calculate backwards and you have a Julian calendar app on your smartphone, the other number on the carton, 009, is the Julian calendar date that they eggs were laid. The Julian calendar date for January 9 is 009, the 9th day of the year. And the last set of numbers, 1129, references the USDA processing plant number where the hens were housed. The eggs in this carton were produced in Pennsylvania. You can look up plant numbers at this website.

For Maine, cartons with the numbers 2101, 2102, 2103, 2104, 2105, and 2108 were all produced at the Moark Farm in Turner.

Oh, and yes, eggs need to be refrigerated after you bring them home from the grocery store and even if you have your own hens.

Dr. Hoenig retired as the Maine State Veterinarian in 2012 and, after completing a year-long Congressional Fellowship in Sen. Susan Collins’ office in Washington DC last year, in January 2014 he started working as a part-time Extension Veterinarian for University of Maine Cooperative Extension.

Dr. Hoenig invites you to submit questions and comments to dochoenigvmd78@gmail.com. Answers to selected questions will appear in future blog posts.