Hemlock Looper

The Hemlock Looper, Lambdina fiscellaria (Guenée), is a native North American moth belonging to the family Geometridae, the second largest family in the order Lepidoptera. The family accounts for many serious agricultural and forest pests, the hemlock looper being no exception. Its larvae are a pest of balsam fir, hemlock, sugar maple, white birch and occasionally spruce and larch trees. In Maine, it has been recorded on every native conifer and many deciduous trees, as well as some shrubs and ornamentals, but the Maine Forest Service lists balsam fir, hemlock and white spruce as being most at risk from hemlock looper.

There are three distinct and regional subspecies of hemlock looper (albeit with some debate): the Eastern Hemlock Looper (Lambdina fiscellaria fiscellaria), the Western Hemlock Looper (Lambdina fiscellaria lugubrosia), and the Western Oak Looper (Lambdina fiscellaria somniaria). The Eastern Hemlock Looper occurs–as its name suggests–in eastern North America, encompassing the Atlantic provinces of Canada west to Alberta, and stretching in the US from Maine to Georgia and west to Wisconsin. As one moves more northward in its range, balsam fir is increasingly preferred, whereas hemlock is its preferred host as one travels farther south.

Life Cycle and Damage

Eggs: Hemlock looper has a single generation per year and overwinters in the egg stage. Eggs are only about 1 mm in length, are laid from late August to October, and are deposited singly or in groups of two or three in a variety of locations including branches, bark, and even the forest floor amongst lichen and moss. Eggs begin hatching in late May and/or early June and continue hatching through about the middle of June.

Larvae and Tree Damage: Larvae are present from late May/early June into August and progress through four to five instars (typically five but in Newfoundland there are only four instar stages). The loopers (inchworms) feed initially on new foliage but soon they switch over to old foliage and will only feed on new foliage again when the old foliage is depleted. They are very wasteful feeders, nipping only a small part of a needle before moving on to another [the photo on page 2 of this USDA Forest Service Pest Alert illustrates the ‘nipping’ or ‘notching’ feeding behavior]. Damaged needles dry out, turn reddish-brown, and later die. Needles are often clipped off, forming a mat below the tree. High populations of the larvae can remove nearly all of the tree’s needles in only a single season! Defoliation is often heaviest in the undergrowth because larvae tend to drop off or fall from their position if they are disturbed. At maturity, larvae reach about 1.5″ in length. By late July, mature larvae begin dropping to the ground to pupate in whatever protected places they can find. In areas with heavy infestations, the trees will be covered with silken strands that the larvae spin and use as ropes when they drop from the branches. Hemlock trees may die after only a single year of severe defoliation. Fir trees may die after one or two years of severe defoliation. Deciduous trees, by contrast, rarely suffer significant damage from loopers. Hemlocks, firs and white spruces that happen to lose more than 70% of their needles from hemlock looper usually suffer long-term effects that sometimes will kill the trees eventually or at least kill individual branches or the tops of the trees. If more than 90% of the needles are lost, significant mortality is seen. The same is true if the trees are defoliated for several seasons

Pupae: The pupae vary in appearance but generally have brown and green coloration as well as dark spots. There is no cocoon formed around the pupa. Pupae are most likely to be found in cracks and crevices on the bole of the tree, in decayed stumps, in spaces in and around moss and lichens, and under any type of debris found on the ground. The pupal stage lasts approximately 22 days.

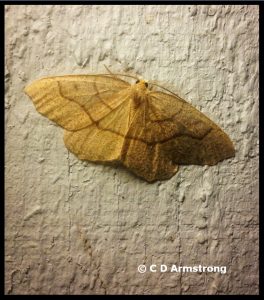

Adults/Moths: Hemlock looper moths begin emerging around the end of August, with emergence continuing until the middle of September. Males often are the first to emerge, by an average of about four days. The moths are small, with a wingspan of about 1.25″ in length, and are colored tan to gray-brown but with a wide variability within the species in the intensity of the colors. When at rest, the moths lay very flat in the shape of a broad wedge. They are active starting in the late afternoon and continuing through the night, from late summer through the fall. During heavy outbreaks, one can find large numbers of moths resting and mating on the tree trunks and on the underlying vegetation. Male hemlock looper moths live for about ten days whereas females live for about 14 days. Each mated female can deposit up to 150 eggs, and since looper moths are weak flyers and consequently don’t travel very far away, populations can be heavy in a localized area, giving rise to very large numbers of eggs per tree.

Outbreak Dynamics

The population dynamics of hemlock looper are poorly understood. During outbreaks, the populations tend to crash after two to three years regardless of weather conditions. Rarely does an outbreak last more than three or four years. Occasionally, however, an outbreak may last six or more years! Infestations are noted for their rapid escalation and sudden collapse, but are usually heavy and long enough—before they collapse—to cause very high levels of defoliation and tree mortality. Outbreaks usually begin as small, often widely-scattered infestations which gradually increase in size and distribution each year (if conditions allow) and eventually begin to overlap to form a single large, irregular outbreak area. The reason for the crash of hemlock looper outbreaks is most likely the work of natural enemies (e.g. viruses, fungi, parasitoids and predators), but the right combination of weather conditions may also be a primary factor. They do not do well during unusually cold and wet summers, and heavy rains during the moth flight period can interfere with mating opportunities.

Newfoundland has had many significant hemlock looper outbreaks in the past, with the period between outbreaks highly variable:

- 1910-1915: 30,000 acres infested and 3,000 acres of dead trees (severe outbreak that killed almost all of the balsam fir over many square miles at four locations)

- 1920-1926: 20,500 acres infested and 15,000 acres of dead trees

- 1929-1935: 141,000 acres infested

- 1946-1955: 315,000 acres infested and 30,200 acres of dead trees

- 1959-1964: 54,000 acres infested and 25,000 acres of dead trees

- 1966-1972: over 2 million acres infested and 273,000 acres of dead trees

- 1989-1993: populations were highly irregular (some went up but others went down);1990 = 39,500 acres infested and 6,400 acres with moderate to severe defoliation; 1992 = 24,200 acres defoliated.

Hemlock Looper Outbreaks in Maine: Damaging populations were rare in Maine until 1989-1992:

- Bath (1927), Wiscasset (1964), and Nobleboro (1966) (only about 151 acres of heavy defoliation in total)

- 1989 to 1992 heavy to severe defoliation of hemlock and fir which expanded quickly from 450 acres in 1989 to over 218,000 acres across the southern half of the state! Stands of balsam fir and white spruce were killed along the coast early in the outbreak. Inland hemlock stands were severely defoliated later in the outbreak and resulted in scattered but significant hemlock mortality.

- Populations crashed during the summer of 1993 (was cool and wet early in the season).

Additional Information and Photos:

- Hemlock Looper (Maine Forest Service)

- Hemlock Looper (Butterflies and Moths of North America)

- Hemlock Looper (Natural Resources Canada)

- Photo of two Hemlock Looper Eggs (ForestPests.org)

- Photo of a mature Larva (Natural Resources Canada)

- Photo of a Hemlock Looper Moth on a person’s hand (Butterflies and Moths of North America)