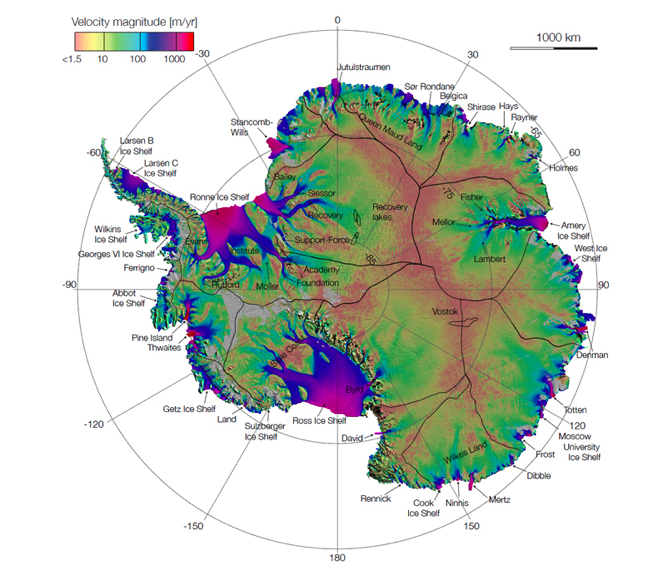

First Complete Map of Antarctic Ice Flow

On Thursday, NASA-funded scientists released the first complete map of Antarctic ice flow. Until now, Antarctic ice flow studies have focused on the outer fringes of the continent, leaving the frozen interior essentially uncharted. The new map illustrates the speed and direction of ice flow across the entire continent, dramatically improving the accuracy with which scientists will be able to track future ice sheet movement and sea-level rise related to climate change.

The map reveals a major mountain ridge in East Antarctica that bisects the continent from east to west. In a video of the findings, you can track tributary glaciers weaving dendritically from the ridge across thousands of miles of the continental interior, eventually feeding outlet glaciers that flow into the sea. The video illustrates the true nature of glaciers as rivers of ice, like tributaries of the Mississippi River feeding from the Rocky Mountains into the Gulf of Mexico.

But how can ice flow like a river of water? While ice is solid under certain conditions, it is actually fairly deformable under high pressure because pressure exerts heat that induces melting and flow. Given that the Antarctic ice sheet is more than one mile thick on average, it exerts plenty of pressure to initiate flow.

A geology professor of mine demonstrated the concept of glacial flow to my class by relating glaciers to pancakes (yes, he pulled out a griddle and started cooking glacier pancakes for us — yes, we got to eat them). Like pancake batter spreading laterally as you pile it on the griddle, glaciers spread laterally as snow and ice accumulates at some topographic high. In both cases, the pressure exerted by the vertical accumulation of material forces that material outward. Theoretically, if a glacier were to build on a uniformly flat and sturdy surface like a pancake griddle, it would form the circular shape of a pancake. This rarely happens. The elongated tributary glaciers on Antarctica have conformed to existing valleys or have carved out pathways through erodible rocks.

Aside from glacial shape, the direction and speed of glacial flow also varies greatly across Antarctica because of its varied landscape. For example, ice flows more quickly in narrow valleys than in broad valleys because narrow valleys channelize thick ice. Thick ice increases friction and heat, creating meltwater along the valley floor. Meltwater lubricates ice movement and increases the speed of glacial flow.

Such concepts in glaciology are well established but, until now, they have never been documented in detail across Antarctica. Now, with velocity data from hundreds of tributary glaciers and cutting-edge evidence that ice flow initiates thousands of miles from the sea near topographic divides, the new map offers a vibrant future for research in ice flow dynamics and global sea-level rise. And, underneath the ice flow velocities, the map reveals an Antarctic landscape of mountains and valleys that has hitherto been a frozen enigma. Yet again, climate change research allows us to become better acquainted with our planet.

Posted by Laura Poppick, Assistant Editor of Maine Climate News.