Loops of Change: the Positive Feedback Loops that Drive Climate Change (Part I)

Sea Ice-Albedo: Earth’s Chilling Reflection

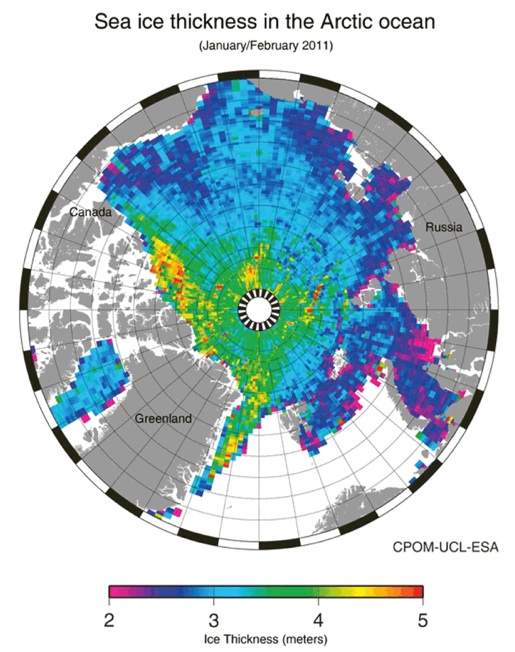

Last month, the European Space Agency (ESA) released the first ever map of polar sea ice thickness. While two-dimensional maps of sea ice extent have been available since 1979, this is the first project to present total ice thickness in addition to extent. The ESA plans to continue updating the map in the future, providing climate scientists with an invaluable record of sea ice response to climate change.

Climate-induced changes in polar sea ice extent depend largely on ice thickness for 2 reasons, the first more obvious than the second: 1) thin ice melts away faster than thick ice, and 2) the absence of ice promotes further melting in a positive feedback loop called the sea ice-albedo climate feedback mechanism.

The sea ice-albedo mechanism is rooted in the simple concept that light-colored surfaces reflect light and dark surfaces absorb light. When you choose to wear light-colored rather than dark-colored clothing on a warm summer day, you are increasing your body’s albedo, or its reflectivity power, and allowing yourself to feel cooler. The same is true on a local scale of dark pavement absorbing more heat and feeling hotter to walk on than the grass around it, and on a global scale of Earth’s surface and atmosphere reflecting more sunlight in light regions (polar ice caps) than in dark regions (open ocean). As the hues of your clothing affect your personal climate, Earth’s surface features collectively manipulate global climate.

Earth’s net albedo, or the percentage of incoming solar radiation reflected back into space, changes with shifts in surface features. It is susceptible to cloud cover, vegetation growth, and even your wardrobe choices. My particularly pale geologist friend jokes that she increases Earth’s albedo when she bares her skin outside — and she’s right.

While everything under the sun does contribute to Earth’s net albedo, only vast expanses can significantly manipulate Earth’s climate. Polar sea ice, for example, is an especially important component of net albedo because it is far reaching, highly reflective, and dynamically involved in global climate as follows:

When sea ice melts, it exposes dark, heat-absorbent open ocean which, in turn,

- decreases net albedo,

- increases regional heat absorption,

- induces further melting,

- further decreases net albedo,

- further increases regional heat absorption,

- and ultimately warms global climate.

This is the sea ice-albedo positive feedback loop.

So why doesn’t sea ice melt away completely during polar summers? Because albedo is just one knob on Earth’s natural thermostat, which hosts many other knobs working in tandem to maintain a relatively stable climate system. ESA’s new ice thickness mapping program will help determine the future stability of this thermostat. Meanwhile, stay tuned for next week’s post on the Solubility Pump: an Oceanic Cooling System to learn how ocean chemistry balances global climate.

Posted by Laura Poppick, Assistant Editor of Maine Climate News.

Loops of Change is a weekly series through July exploring the major positive feedback loops that drive climate change.