Research Highlights: Are Maine’s salt marshes drowning?

By Kristin Wilson, Doctoral Candidate at the University of Maine

Salt marshes are critical components of our coastal environments. They intersect upland runoff and act as filters, improving water quality before it enters our nearshore waters. They buffer and stabilize our coasts from large storm impacts, like hurricanes. And finally, they offer essential nursery habitat for juvenile fish and shellfish, and serve as links between coastal and marine food webs.

Many salt marshes are experiencing an alarming trend, however. All along our coasts, large expanses of salt marshes are being lost, disintegrating and disappearing at rates so rapid they are noticeable from year to year. Such changes are disturbing because a loss of our salt marshes means a concurrent loss of the important ecosystem services they provide.

What’s going on? Studies of salt marshes along the Gulf Coast and Mid-Atlantic indicate that salt pools are partially to blame. Salt pools are shallow, water-filled depressions that are common features of salt marshes. They range in size from the very small (one square meter) to the very large (>100m2). Pools provide habitat for aquatic plants and animals, especially young fish and decapod crustaceans, or nekton, and are significant forage sources for wading shore birds and ducks.

Though salt pools are common features of salt marsh environments, their role in governing the structure and formation of salt marsh processes is not well understood. Ongoing research indicates that salt pools are dynamic, an idea that contrasts with the previous thought that pools are more permanent features. As sea level rises due to climate change, pools grow, merge together, and eat away at the vegetated marsh surface to create open water bays. This conversion results in a loss of the marsh surface and with it, the valuable services the marsh provides.

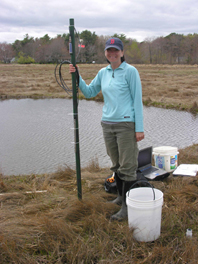

Is this process occurring in Maine? My Ph.D. research asks this question and what the answer might mean for our nearshore systems and coastal policies. My work is exciting because it integrates the fields of ecology, geology, and spatial information science to study salt pools and document patterns of surficial change for five Maine salt marshes (Ogunquit, Brunswick, Gouldsboro, Addison, and Lubec) over the past 100 years. Our preliminary results suggest that Maine marshes are keeping pace with sea level rise, but our ongoing work continues to address this important question.