Climate Highlights from Around Maine: Maine’s Climate Future: Coastal Vulnerability to Sea-Level Rise

Maine’s diverse coast is home to the majority of the state’s population. It also attracts millions of visitors each year, sustaining Maine’s valuable tourism industry. Working waterfronts support fishing, shipbuilding, and related marine businesses. All of these people and activities coexist at the fragile edge where land meets the sea.

Coastal hazards are not new to Maine. Coastal communities have been dealing with storms and related flooding and erosion for generations. However, an increasing sea level likely will increase the impacts of these coastal events. If the rate of sea-level rise exceeds the rate of sediment delivery to beaches, dunes, and marshes, this could result in land loss and instability of coastal ecosystems.

This fact sheet presents the current state of knowledge on sea-level rise and its impacts on Maine’s coast. This publication was created in response to the need for more specific sea-level rise information identified during the statewide climate change adaptation stakeholder process [www.maine.gov/dep/oc/adapt/] coordinated by the Department of Environmental Protection. Additional fact sheets in Maine’s Climate Future series are under development. For more information, contact Catherine Schmitt.

Sea-level rise past, present, and future

Historically, sea-level changes in Maine have been highly variable, as the land responded to the growing and shrinking glacier of the last ice age. The shoreline has ranged from as far inland as Medway and as far seaward as Georges Bank, which was exposed as an island when sea level reached its lowest elevation 12,500 years ago.

During the last 5,000 years, sea level rose very slowly, a rate that allowed today’s beaches, sand dunes, and marshes to form from the sediment carried by rivers and re-worked by waves.

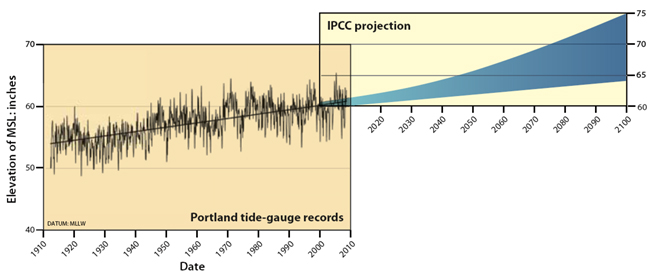

Modern-day measurements at a tide gauge in Portland show that sea level has risen at a rate of about two millimeters per year (mm/yr or 0.07 inches/year or 0.6 feet over a century). Although this doesn’t seem like much, it is the highest rate in the last 5,000 years.

Maine Sea Level, 1912-2100

Tide-gauge records in Portland, Maine, show a sea-level rise of 0.07 inches per year (1.77 mm/yr) since 1912 (Belknap 2008). The 2007 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projection of another one-foot rise in sea level by century’s end is considered conservative by many scientists.

Based on data released by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2006, Maine adopted a planning scenario in the Sand Dune Rules of a 50% chance of a two-foot rise in sea level by 2100.

Why is the sea rising along the Maine coast?

- Thermal expansion: As the atmosphere gets warmer, the ocean heats up and expands.

- Volumetric increase: The volume of the ocean increases with water from melting glaciers and land-based ice sheets.

- Subsidence: There is a slight regional subsidence of the coast.

Sea-level rise and the Maine coast

Sea-level rise is just one of several factors that influence how the coast responds to hazards; others include land use, geology, tides, currents, and sediment volume. While scientists can’t always predict what will happen to specific stretches of shoreline, they can make reasonable predictions for certain coastal features.

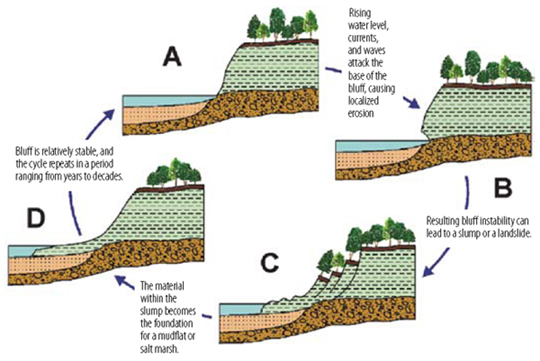

Bluffs

Much of Maine’s outer coast is steep and rocky and resistant to rising water levels. About 46% of the coast—over 1,400 miles—is comprised of bluffs formed from soft, loose sediment. Future bluff stability will vary based on the frequency of wave or storm attack, the exposure of the bluff to storm waves, and the ability of the bluff to lose sediment at a rate that would maintain a protective wetland or marsh in front of it. These features will continue to erode and move landward in the face of rising sea levels. The Maine Geological Survey and the Maine State Planning Office analyzed the distribution of coastal bluffs, the severity of erosion, and the extent of shoreline engineering along the coast, and found that at least 40% of Maine’s coast is vulnerable to increased erosion at higher sea levels.

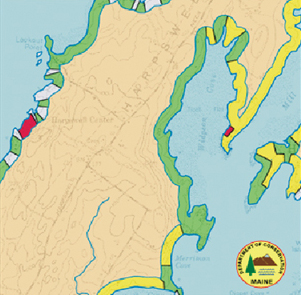

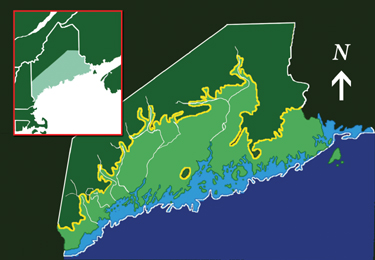

Vulnerable Shorelines: Red, Yellow and Greens

- MGS Coastal Bluff Map

- MGS Coastal Landslide Hazard Map

For more details see the MGS website.

Bluff response to sea-level rise and storms

Tidal flats, Salt Marshes, and Freshwater Wetlands

Tidal flats and salt marshes exist in a very narrow zone between the tides and are probably the most susceptible habitats to sea-level rise in Maine. Small changes in sea level can change the pattern and frequency of tidal flooding, resulting in major changes in the type and extent of flats and marshes.

Tidal flats may be flooded too frequently to serve the millions of hungry shorebirds that visit on their annual migrations. In other areas, eroded sediment could smother commercially important shellfish habitat.

Infrequently flooded “high” salt marsh environments, particularly in southern and mid-coast Maine, could revert to “low” salt marsh habitats, or become open water where development or steep slopes block their landward migration. If sedimentation rates can keep up with sea-level rise, the marsh systems may maintain themselves for some time. It is likely that the overall structure of the marsh will change to a more dynamic mixed- or low-marsh dominated system, and some marshes will be lost altogether.

Freshwater wetlands and bogs are often located adjacent to tidal wetlands. Sometimes only a slight difference in topography separates the two, and as sea level rises, salt marshes can expand into previously freshwater marshes. Salt water that creeps into freshwater bogs and marshes can kill plants, hastening land loss. This air photo shows a tidal flat, salt marsh (light color) and freshwater bog (dark color) in Jonesport. Marine environments have the potential to rapidly replace freshwater systems with rising sea level.

Beaches and Dunes

Although they only make up about 2% or roughly 70 miles of Maine’s coastline, beaches and sand dunes serve as the primary means of shoreline protection along the sandy coast. Beaches and dunes also experience some of the most intense development pressure. Typically, beaches and dunes respond to rising seas and coastal storms through the processes of overwash, when high tides and storm surge wash over the beach and break through the dunes, depositing sand behind the dune or carrying sand back into the sea. Slowly, the entire beach system rolls over itself and migrates landward (a process called “transgression”). The response of beaches to sea-level rise depends on the relationship of the sedimentation rate to the rate of sea-level rise, and also whether or not the beach or dune has the ability to migrate inland. Beaches that have limited sediment supplies or no room to migrate will likely erode in a much shorter period of time and could potentially disappear. Tree stumps on the beach and mudflats at Scarborough’s Ferry Beach are evidence of beach and dune transgression.

Coastal Aquifers

Some coastal residents get their drinking water from wells drilled into fractured bedrock aquifers that are susceptible to saltwater intrusion. With increased sea levels, saltwater contamination of drinking water could become more widespread and problematic.

Coastal Infrastructure

The majority of Maine’s population resides in the coastal zone. Development and related infrastructure—roads, water, and sewage treatment facilities, piers and homes—are damaged or impaired by flooding and storm surges. Increased storm frequency and intensity, combined with rising sea level, makes all storms more damaging, with serious economic and ecosystem consequences to the region and state. Economists Charles Colgan and Sam Merrill of the University of Southern Maine found that in York County alone, over 260 businesses representing $41.6 million in wages are at risk from coastal flooding and the resulting property destruction and higher insurance costs.

Responding to change and building a resilient coast

One way that Maine has already acted to address the threat of sea-level rise is through the Natural Resources Protection Act’s Sand Dune Rules and shoreland zoning program. These rules anticipate future shoreline changes from a two-foot rise in sea level by 2100, based on the best data available at the time of rulemaking. This scenario is a conservative estimate because current sea-level rise projections do not account for potential freshwater input from the melting of the Greenland or Antarctic ice sheets. The Sand Dune Rules allow communities to plan for the sea-level rise; in reality, however, coastal managers are already dealing with many of the problems expected to result from sea-level rise, storms, and flooding. But they need tools to identify locations and properties that are vulnerable to inundation, so they can make decisions about where and when to build piers, roads, houses, wastewater treatment plants, and other infrastructure. For example, current UMaine research is beginning to map freshwater wetlands at risk from rising sea level and to predict their rate(s) of transformation. In the past, people responded to the threat of erosion by building seawalls, bulkheads, and other barriers; at least 152 miles of bluffs, or about 5% of the coast, are armored with these “hard” structures. Today, managers recommend “soft” engineering structures that protect coastal property without worsening erosion elsewhere. Taking a neighborhood or community approach, rather than protecting individual properties, benefits everyone.

- Photo by C. Schmitt

- Photo by C. Schmitt

- This fact sheet was produced as a supplement to Maine’s Climate Future, published in 2009 by the University of Maine. For more information on that report and research, visit the Climate Change Institute website.

- For the latest information about climate change in Maine, and for a PDF of this document, visit the Maine Climate News website.

- Video and resources about building a resilient coast are available on the Coastal Community Resilience page, Sea Grant Maine website and Maine.gov’s website, ‘coastal erosion/building a resilient coast’ search page

Edited by Catherine Schmitt, Maine Sea Grant

PDF designed by Kathlyn Tenga-Gonzalez, Maine Sea Grant

With contribution and review by Esperanza Stancioff, University of Maine Cooperative Extension and Maine Sea Grant; Peter A. Slovinsky and Stephen Dickson, Maine Geological Survey; Joseph Kelley and George Jacobson, University of Maine; and Elizabeth Hertz, Maine Coastal Program.