Climate Highlights: Climate Change and Bird Migration in Maine

By Laura Poppick

Maine and the birth of American birding culture

Roger Tory Peterson, legendary ornithologist and creator of the influential Peterson Field Guide series, ignited his early birding career working as a counselor at the Chewonki camp in Wiscasset, Maine, and then teaching at the very first National Audubon Nature Camp for Teachers on Hog Island when it opened in 1936. In his memoir All Things Reconsidered: My Birding Adventures, Peterson described revisiting his ‘beloved islands’ in the Muscongus Bay for the camp’s 50th Anniversary, unable to fight back tears for his fondness of the place.

Peterson’s easy-to-read and beautifully illustrated book series set a new standard for modern field guides and spurred a new American interest in birding that continues to thrive today. According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, birding is currently the second fastest growing hobby in the United States after gardening. Delta Willis, senior communications manager for the National Audubon Society, believes the trendiness of birding will continue to increase with the unsteady economy. “People are really looking for something cheap, cheerful, and accessible,” Willis said. “You can go birding from anywhere, and it’s family friendly.”

Ornithologists welcome this burgeoning bird enthusiasm, as they often rely on citizen-scientists to volunteer their bird sightings for the sake of long-term studies. With more eyes in the field, patterns more readily unfold. And, recently, strange new patterns have many birders wondering how climate change may be affecting local bird populations.

“Robins used to be a sign of spring,” Willis pointed out. “Now they appear throughout the winter. With climate change, we frequently get calls from people who are noticing birds coming up in their neighborhood that were never there before.”

Though pleased to tally up these exotic new species on their life lists, birders realize that such anomalous sightings carry complicated implications for the future livelihood of migratory birds. Ornithologists across Maine are focused on how Maine birds will cope with change.

Climate Change and Bird Migration in Maine

Over the past 17 years, Colby College biologist Herbert Wilson has tracked spring arrival dates of 107 migratory bird species in Maine. With the help of over 200 citizen-scientists, he has collected more than 32,000 observations that cumulatively show only a modest relationship between climate change and spring arrival date.

But, as the onset of springtime occurs earlier and earlier, Wilson suggests that more dramatic changes in migration will gradually unfold. Birds that rely on early-spring food, such as seeds that appear before leaf-out, are increasingly challenged to properly synchronize their arrival date with food availability. Arriving before or after prime feeding time jeopardizes their own strength for winter migration and their chicks’ ability to fledge.

And, while springtime feeding is an immediate concern upon arrival in Maine, it is only one component of the annual migration cycle. “Events that occur anywhere during the yearly cycle are not independent of previous or subsequent events,” explained UMaine ornithologist Rebecca Holberton. “If birds are in a poor habitat during the wintering period, they won’t prepare well for migration. They may delay their departure, which may ultimately delay breeding and de-synchronize their feeding schedule.”

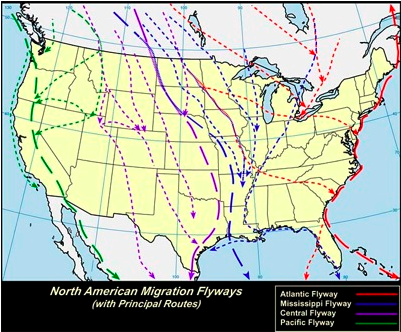

Migratory animals, including birds, face more complex climate-related challenges than more stationary animals. “An individual bird covers so much ground, and has to adjust to many regionally specific changes,” explained UMaine ornithologist Brian Olsen. “They have to cope with changes in Mississippi River water quality to the loss of permafrost in the Arctic tundra.”

Migrants may, in fact, be more resilient to climate change than their non-migratory counterparts, since they are innately versatile and genetically built to survive diverse environmental conditions. Olsen and other ornithologists in Maine are still testing this optimistic hypothesis, species by species.

Spotlight: Puffins and Climate Change in Maine

The Atlantic puffin is a Maine icon and helps draw thousands of tourists to the state each year. Extinguished from the region by hunters in the late 1800s, puffins have made a resilient resurgence over the past several decades thanks to the Project Puffin initiative launched by ornithologist Steve Kress in 1973.

Now, the Maine puffin population faces new threats posed by changes in ocean currents associated with climate change. “Increasing atmospheric temperatures are increasing freshwater flow from melting ice in the Arctic, which increases the stratification of the water column and, in turn, affects ocean circulation in the Gulf of Maine,” explained ecologist Sigrid Lehuta at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute in Portland.

Puffins prey predominately on herring, a highly nutritious fish, to feed their chicks and fuel themselves for fall migration. Herring depend on cold, nutrient-rich deep-water currents to support their planktonic food source. Since freshwater is less dense than seawater, Arctic ice-melt flows above deep-water currents and creates a barrier that limits deep nutrients from mixing to the surface, explained UMaine oceanographer Peter Jumars. Weakened mixing appears to be weakening the Gulf’s ecological framework that supports herring, and may be responsible for recent declines in herring stock.

Puffins have shown a great capacity to hunt new fish species, but this capacity does not necessarily compensate for the inferior nutritional quality of the alternative prey. “We see puffins bringing in butterfish, but the chicks can’t swallow them because they are flat,” explained Holberton. “Chicks sit next to a pile of butterfish, unable to eat them.”

Inadequate food supply may explain the unusually late departure of puffins from Machias Seal Island this year, according to observations reported by lighthouse keeper Ralph Eldridge, who suggests that the birds stayed around longer to properly fuel their travels. Hurricane Irene brought further disturbance to Machias nesting sites, washing away between 150 and 200 chicks in particularly vulnerable areas. Increasing sea level and hurricane severity associated with climate change, in tandem with degraded nutrient supplies, all threaten the livelihood of this Maine icon.

An Inspiration for Future Sustainability in Maine

The growing bird enthusiasm in the U.S. will only help birds cope with environmental change, believes Rich MacDonald, founder of the Natural History Center in Bar Harbor. “Historically, birding was a genteel activity. Now, increasing numbers of young people are becoming birders. Young birders appreciate the fact that we have to have good habitat, that we have to protect good habitat, to sustain bird populations.”

Meanwhile, having just celebrated its 75th Anniversary this past August (Audubon Hog Island Camp in Maine Celebrates 75th Anniversary, Audubon website), the Hog Island Audubon Camp is attracting more younger campers to connect with their environment through birds. Marine extension associate Chris Bartlett nostalgically remembers working on the island as a teenager. “The camp introduced me to some very wonderful experienced people who taught me the power of observation in the natural environment. I just learned so much that summer in that regard.”

Now, Bartlett is part of a team of environmental consultants assessing how the Maine Tidal Energy Project in Cobscook Bay will affect local seabird populations. Preliminary data suggest that the tidal turbines do not appear to be a significant threat to puffins and other birds. Forging the way towards sustainable energy, Maine is once again at the forefront of an environmental movement inspired by and supportive of birds.