Fall 2009-Winter 2010: A Remarkable Season

By Dr. George L. Jacobson, Maine State Climatologist

Dr. George L. Jacobson, Maine State ClimatologistInteresting examples of weather patterns continued throughout 2009 and into the first six weeks of 2010. As we think back on the period from mid-summer to the present, several “odd” occurrences come to mind. For example, after the extremes of what seemed to many as excessive rainfall last June and July (excessive in the sense that summer fun was limited during that time), we had a stretch of pleasant and seasonal weather through the late summer and early fall.

But then in October, we experienced a stretch of cold, wet weather that felt more like winter than it did leaf-watching season. In fact, for much of the month, furnaces and wood stoves were in use as if winter really was here. We weren’t just imagining the cold, either; October 2009 was the sixth-coldest of the past 115 years.

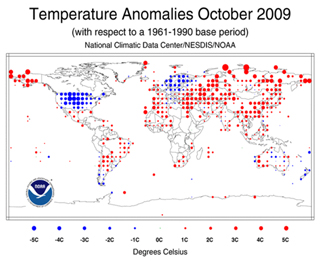

The cold air extended far beyond New England, as the Arctic air spread southward over much of the country, bringing surprisingly cold conditions all the way down to Texas and Florida. While large cold-air masses do tend to drop down into the southern states a few times during most winters, this early movement of cold was quite unusual. In fact, October was anomalously cold over most of central North America and Western Europe, as the map below illustrates. While North America and Europe were unusually cold, most of the rest of the world was unusually warm, especially Arctic regions and northern Asia. In fact, based on average global temperature, 2009 had the sixth-warmest October since 1880.

The Earth’s temperature has to balance. When one place is unusually warm, then another is unusually cold. The solar radiation that enters the atmosphere gets distributed around the planet—more heat in one area takes heat away from other areas.

In Maine, once we passed the cold October weather, the rest of autumn and the first half of winter were quite warm. November was the fourth-warmest since records have been kept; December was also warmer than normal. And January and the first half of February 2010 have been well above normal. For Maine, the average January temperature was more than 7.3oF warmer than expected (tenth warmest since 1985), and February was 8.7oF warmer than expected (second warmest since 1895).

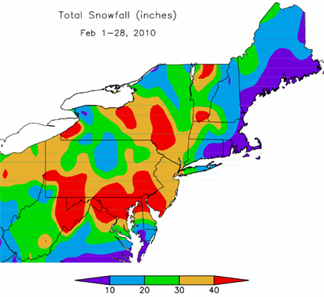

At the same time, we have watched a series of large winter storms across the mid-Atlantic states, leaving Washington, DC, and neighboring cities buried in snow. As a result of the storm track for these storms being more than usual to the south, the total snow accumulation varied accordingly, with much less in Maine that we would have expected.

These unusual weather patterns are used as evidence to support one view or another about climate change. Some have argued that the cold weather in the south and the storms in the mid-Atlantic region show that “global warming” can’t be taking place. Others suggest that these odd weather patterns are just what “global warming” will produce.

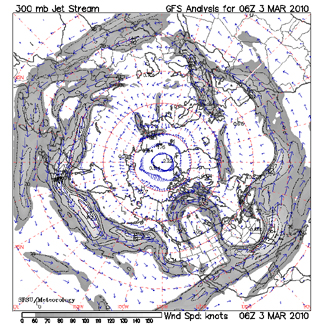

Of course, neither of these arguments are true. Weather patterns are weather patterns, and there is tremendous variability from one period to another. In fact, many of the conditions described above (the October cold snap right up to the three winter storms that closed our nation’s Capital), have more to do with the position of the jet stream than anything else. The term jet stream usually refers to high-altitude winds occurring at the boundary between temperate and Arctic air. These west-to-east flowing winds move around the earth with a path that usually has four to six lobes. The exact position of the flow changes through time, but often the configuration stays fairly constant for weeks at a time. The routes of aircraft flying long distances at high elevations are heavily influenced by these winds, as the planes use them to advantage when flying to the east, and do their best to avoid them flying west.

The movement of air masses is quite complex, but a simplified version is that when those lobes extend far to the south, cold air from the north can penetrate to those regions, as happened in October. The position of the jet stream also determines the likely path of storms. Thus, when we see weeks go by with storms passing along the same path (whether it over us or over the Washington-New York corridor) it is because the configuration of the jet stream is remaining in a similar place (see image below). We have experienced mostly sunny, pleasant winter weather while the mid-Atlantic region has been socked largely because the jetstream remained in that position.

All of these are wonderful examples of the fascinating variability in weather, as opposed to climate. The long-term consequences of adding carbon dioxide, methane, and other greenhouse gases to the Earth’s atmosphere are certain to involve significant differences in the mean position of the jet stream and the associated weather patterns. But we can never say that any blizzards, hurricanes, cold snaps, hot spells, tornados, or even a season of unusual weather phenomena, result from anthropogenic (human-caused) greenhouse warming. The consequences of our massive additions of heat-trapping material to the atmosphere will be significant, but they will be evident only in statistical patterns that demonstrate changes that span extended periods of time. Then we will be in climate.

NOAA reports that January 2010 is globally the fourth warmest on record

In fact, NOAA and NASA have each recently reported that the first decade of the 21st Century was the warmest during the instrumental record. That and the data from the warm few decades that preceded it are the beginning of the kind of record that will provide perspective about long-term changes in climate. But even these sequences are influenced by a number of other complexities of our climate. Fortunately, research here at the University of Maine and elsewhere is providing evidence about how the Earth’s natural climate varies over geologic time and up to the present.

In the coming installments, we will discuss climate variability at different time scales, and review some of the ways that we can make informed judgments about human influence on the Earth’s climate.