Small Volcanic Eruptions Cool the Climate

On August 27, 1883, civilians on the Indian Ocean island of Rodrigues heard an explosion. What they initially assumed was cannon fire from a neighboring ship turned out to be a more distant threat: the sound of a volcano erupting on Krakatoa, Indonesia, nearly 3,000 miles away.

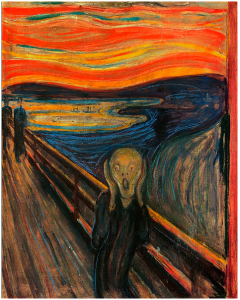

Traveling 50 miles through the atmosphere into the stratosphere, aerosols from the volcano’s ash plume billowed over the Earth along air currents that tinted the global sky for several years to follow. This veil of aerosols reflected enough incoming solar radiation to lower global temperatures by 2.2°F, and cast a dramatic red glow on skies above the U.S., Europe, and Asia. The brilliant sunset in Edvard Munch’s The Scream was allegedly inspired by these Krakatoan skies.

Until recently, atmospheric scientists assumed that only such catastrophic eruptions could significantly alter Earth’s climate. Other eruptions of similar scale have been documented to have temporarily cooled global climate, with the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia causing a ‘year without a summer’, and the 1991 eruption of Pinatubo in the Phillippines cooling global temperatures by nearly 1.0°F.

Now, NOAA scientists say that even small volcanic eruptions can manipulate global climate. In a paper published last month in Science, Susan Solomon and her team report that ‘background’ levels of global stratospheric aerosols have nearly doubled over the past decade and have slowed the trajectory of climate warming. Given that no catastrophic volcanic eruptions have occurred since the 1991 Pinatubo event, other sources must account for this recent increase in aerosols. Some argue for coal burning power plants in China, but NASA scientist John Vernier and his team point to a series of moderate low-latitude tropical volcanic eruptions.

Low-latitude volcanic plumes rise above the equator and spread across both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres like tape in a cassette. High-latitude volcanic plumes, on the other hand, generally remain contained within their hemisphere of origin. Vernier shows that a series of increasingly more intense but still relatively moderate tropical eruptions have substantially contributed to the steady rise in global stratospheric aerosols over the past decade.

While the cooling effect of stratospheric aerosols is relatively fleeting, lasting up to 2 or 3 years, it is still significant in global climate. And yet models that predict future climate change do not generally account for volcanic aerosols. Solomon and Vernier both encourage climatologists to place more weight on volcanic aerosols to improve the accuracy of climate models.

Posted by Laura Poppick, Assistant Editor of Maine Climate News.