2: Starting a New Municipal or Regional Climate Adaptation Initiative

- 2.1 Creating a Team

- 2.2 Celebrate Your Current Successes

- 2.3 Defining Resilience

- 2.4 Generating Resilience Goals

- 2.5 Principles of Resilience for Community Leaders

- 2.6 Setting Up for Success Using a Resilience Building Framework

Alignment with State and Maine Climate Council Strategies

- Strategy F: Build Healthy and Resilient Communities

- Strategy H: Engage with Maine People and Communities about Climate Impacts and Program Opportunities

Why adapt to a changing climate in this region?

- Prepare the people, places, and environments that we care for

- Save money for communities and individuals by avoiding chronic repairs and damage

- Preserve each community’s ways of life

Maine State Climate Plans recommend establishing a center of gravity for municipal climate initiatives, identifying lead points of contact, and empowering those individuals and teams by creating underlying, common objectives, goals, and ‘frameworks’ to ensure communities adopt consistent, effective, and measurable strategies. Informative decision-making questions and criteria can be tailored for each community’s needs and help to design projects and evaluate the effectiveness and broader impacts of adaptation responses and measures.

2.1 Creating a Team

Successful development and implementation of adaptation and resilience projects hinge on establishing points of contact within municipal and Tribal government. Progress on climate action is often carried out through the dedicated work of small teams, often with supporting partners. This could include establishing a new committee, tasking an existing committee with new climate change-related initiatives, or designating staff or volunteers to coordinate activities.

Coordination across government, with multiple points of input, can align and reinforce priorities for proactive and preventative responses. In the spirit of working together for long-term success, groups can share lessons and identify and agree on solutions. As described more fully below, equity should be a priority, with a commitment to high standards for participation and inclusion and a focus on vulnerable groups, including the risks they face and social impacts across the community.

Working in teams builds a sustainable foundation for continuity of work over time as multiple people participate with different roles and fluctuating levels of engagement. This approach creates information flow across coordinators to other team members and partners and reinforces the principle that each project presents an opportunity while increasing the likelihood of including climate change solutions across all projects.

2.2 Celebrate Your Current Successes

When climate change service providers begin working with communities, it is not uncommon for municipal officials to articulate that their town has taken few or no steps for climate change preparedness. Quotes from town officials like, “keeping up with day-to-day needs often takes priority [over work on climate change],” illustrate that climate resilience may be viewed as a discreet series of actions rather than an overarching factor in municipal activities.

However, the scope of municipal and Tribal governance responsibilities and the often-bustling pace of decision-making and project implementation regularly show a portfolio of efforts focused on the same issues which are most important to climate change experts. The priorities of public works departments, the ongoing activities of emergency management agencies, and current town planning efforts across municipalities in Maine consistently relate to the environmental and societal challenges which are exacerbated by climate change. Remember to take stock of what has already been done, use that information to inform planning and future projects, and most importantly take a moment to celebrate your current successes.

Much can be accomplished, and often already is in small or larger ways, by incorporating best practices for climate change into ongoing municipal activities. Interest in thinking long-term about climate change risks and developing community resilience to coastal hazards is common among government officials. Sea level rise, storm surge, and flooding (coastal and inland) are often vocalized concerns among public officials in Maine. Additionally, common concerns include erosion, saltwater intrusion, wind damage, drought, heat waves, and the impacts of ocean climate change on fisheries, or agriculture, and natural resource industries. As a result, communities are simultaneously interested in strategically incorporating climate change into near-term identified projects, and in taking a broader whole-community approach to assessing risk for holistic climate change planning, prioritization, or reprioritization. For example, efforts to replace or enlarge stormwater conduits, tackle place-based coastal erosion, or augment emergency management, resource management, or town zoning in response to changing flood occurrences, are all practical opportunities to incorporate climate science.

2.3 Defining Resilience

Resilience refers to the ability of any individual, community, or system to prepare for and respond to social and environmental challenges in ways that allow it to bounce back or bounce forward. Using an example of inland flooding along the Kennebec River, community resilience would be demonstrated when the people who live nearby understand their vulnerabilities (i.e., risk or exposure to harm), can organize opportunities for informed deliberation about responding as homeowners and as a community, and can acquire the needed resources to carry out informed decisions. Adaptation is the suite of actual responses to climate change, in this case, what is done by homeowners and the community about the increased risks associated with flooding. Adaptive capacity refers to the social and technical skills and strategies that are collectively available for individuals and communities to build resilience to climate change hazards. Examples include the ways in which people in a community connect with each other, learn, generate ideas, tap into diverse forms of leadership, and respond to all kinds of transitions or challenges. Finally, hazard mitigation is any sustained action taken to reduce or eliminate the long-term risk to human life and property from natural hazards.

Returning to the Kennebec River example, an important aspect of adaptive capacity includes how information about flood risk to riverside infrastructure is communicated and understood by stakeholders and decision-makers, as well as the formal and informal relationships between stakeholders and decision-makers that enable consensus, problem-solving, and adaptive action. The community may decide to have the town purchase homes with the most chronic risks and repurpose the land while other homeowners may opt to fortify structures to safely handle occasional flooding. With better and broader adaptive capacity, specific climate adaptations and outcomes for communities are improved and diversified.

Another concept included throughout the Workbook is climate mitigation, human intervention to reduce the rate of climate change by limiting greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere through natural processes, technological processes, or behavior change. Putting this all together, climate mitigation reduces the rate of climate change and the amount of climate change in the future. Because of the lag time in the climate system due to reductions of greenhouse gas emissions, the dividends of climate mitigation actions taken now won’t be seen in the atmosphere for several decades (by the mid-21st century). Climate change impacts projected now for the next thirty years are therefore highly likely. Adaptation and hazard mitigation are the actions taken to reduce vulnerability to the impact of climate change presently and in the future. Resilience can be an outcome or ability achieved through the cumulative effect of adaptation and hazard mitigation actions.4

2.4 Generating Resilience Goals

It is important to generate goals to help guide workflow. The Maine Climate Council made use of four overarching goals to develop the 2020 Maine Climate Action Plan. They are provided here as examples as they encompass a few of the major areas where climate change actions are taken. These may also be helpful as a starting point for municipal discussions that can be used or adapted for a town’s use.

- Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions

- Avoid the Impacts and Costs of Inaction

- Foster Economic Opportunity and Prosperity Today

- Advance Equity through Climate Response

When developing climate action goals, it is important to remember that climate change mitigation actions, hazard mitigation, and adaptation actions are a part of everyday work and can lay the foundation for healthy communities and a sustainable economy. For example, when pairing solutions for energy modernization, diversification, and reliability with emergency preparedness and adaptation designs, the adaptive capacities to system shocks are also built-in, resulting in more resilient communities. To be more specific, by diversifying the ways electricity is generated and distributed, such as through solar, wind, and other renewable sources of energy that can separate the grid into smaller regions, we can reduce emissions while isolating areas from system-wide shocks and can reduce the duration and frequency of power outages from storms in the process. With the impacts of current greenhouse gas emissions “baked into” the climate system, investments to reduce emissions now while also adapting to near-term impacts is prudent and practical.

Alignment with the Maine Climate Action Plan Goal to Advance Equity through Maine’s Climate Response

The Maine Climate Council is working to ensure the benefits of climate adaptation projects are shared across communities. This started with a Mitchell Center report on Assessing the Potential Equity Outcomes of Maine’s Climate Action Plan: Framework, Analysis and Recommendations, Senator George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions, September 2020 (PDF) which led to the formation of an Equity Subcommittee (Maine.gov) and an in-depth process of providing equity-focused recommendations to shape the implementation of Maine’s four-year climate action plan, Maine Won’t Wait, December 2020, Maine.gov (PDF).

The CRW draws from the Mitchell Center’s report to define equity in the following way:

“Equity takes into account the fact that systems of oppression keep certain people from accessing resources, and an equitable system seeks to provide increased resources to marginalized and disadvantaged communities. The risks and effects of climate change disproportionately fall upon people of color and low-income populations. It is, therefore, absolutely critical that policies intended to mitigate climate change or increase adaptive capacity to its impacts do not exacerbate existing burdens and, wherever possible, increase wellbeing and address the root causes of inequality.”5

The Mitchell Center report provides an equity framework that can help guide community resilience and climate adaptation planning. This framework highlights the need to pay attention to (1) the social impacts of any proposed project and/or climate change impact, including changes in wealth, health, and accessibility; (2) types of vulnerable populations and impacts on financial, social/demographic, and geographic vulnerabilities; and (3) participation and inclusion, including whose voices are represented and if participation is accessible, adaptable to the needs of different groups, and where participation meaningfully influences a project or plan. The focus on participation and inclusion is also often described as procedural equity.

2.5 Principles of Resilience for Community Leaders

As community leaders and public officials establish climate initiatives, create goals, develop plans, and engage in greater depth on topics of resilience, adaptation, and climate/hazard mitigation, it may be helpful to acknowledge that the processes of good governance for climate change likely mirror many practices of effective community governance already in place at the local level. The examples below are guiding principles and considerations for your community’s engagement in climate change resilience and adaptation.

Guiding Principles:

Provide leadership: Ensure that the impacts of climate change and extreme weather are considered across decisions in local government and civic life.

Develop guidance: Create common objectives, principles, and evaluation criteria for project and program review. Ensure the overarching guidance is integrated into governance, organizational structure, and coordination across partners.

Reduce vulnerabilities: A first step toward adapting to future climate change is reducing vulnerability and exposure to present climate variability.

Engage for synergy: Significant co-benefits, synergies, and tradeoffs exist between mitigation and adaptation and among different adaptation responses; interactions occur both within and across regions.

Center climate co-benefits: Often, municipal operations or routine maintenance of public infrastructure can be adapted to further incorporate projected extremes of climate change (e.g., drought and heavy precipitation, summer heat waves, or storm surge on top of sea level rise. Accordingly, considering climate change across municipal activities can yield climate co-benefits and may have only marginal additional upfront costs when compared to non-climate-friendly designs. Incorporated climate resilience is a co-benefit to routine activities. Simultaneously, many mitigation and adaptation approaches to climate change yield other community and environmental benefits. For example, urban shade trees planted for heat waves benefit community development and capture carbon, electric school buses reduce air pollution, and coastal roads built to accommodate sea level and intensifying storms benefit coastal habitats and Maine’s fisheries. Identifying co-benefits clarifies why efforts are valuable across diverse community interests.

Anticipate context-specifics: Decisions are most effective when they are place- and context-specific. No single approach for reducing risks is appropriate across all settings. Employing a place- and context-specific approach (1) requires that those involved in the planning recognize the diverse perceptions of risk, approaches to decision-making, and compounding influences on adaptation; and (2) underscores the importance of coordination across other adaptation or related hazard mitigation and emergency response plans.6

Be inclusive: Adaptation planning and implementation at all levels of governance are contingent on societal values, objectives, and perceptions of risk. Recognition of diverse interests, circumstances, social-cultural contexts, and expectations can improve decision-making processes and lead to successful implementation. Processes should fully recognize and respond to local context, the diversity of decision types, processes, and constituencies including the diversity of approaches taken by intersecting organizations, sectors, and communities.

Maximize resource potential: Existing and emerging economic instruments can foster adaptation by providing incentives for anticipating and reducing impacts.

Design for scale and scalability: Take a landscape-scale approach to decision-making regarding patterns of development, incorporating natural and working lands, past and future uses, natural hazards over time, and environmental, economic, and social impacts.

Common Challenges:

Even when you’ve considered each of the principles above, projects and community initiatives can face obstacles. Thinking in advance about appropriate planning and carefully considering constraints and funding can help communities to overcome many of the common challenges associated with building long-term resilience to climate change.

Appropriate planning: Poor planning could lead to overemphasizing short-term outcomes or failing to anticipate consequences sufficiently which can result in maladaptation. Additionally, emergency management plans or emergency operation plans can be leveraged for cohesion across adaptation and hazard mitigation actions.

Adequate resources: Limited financial and human resources, governance coordination, impact uncertainty, differing perceptions of risks, competing values, absence of adaptation advocates and leaders, and limited tools to monitor and measure adaptation effectiveness can interact to impede adaptation planning and implementation. However, incorporating climate change into the way projects are designed and implemented can best make use of existing funding, which is a fundamental way to close the gap between adaptation needs and funds available for adaptation.

2.6 Setting Up for Success Using a Resilience Building Framework

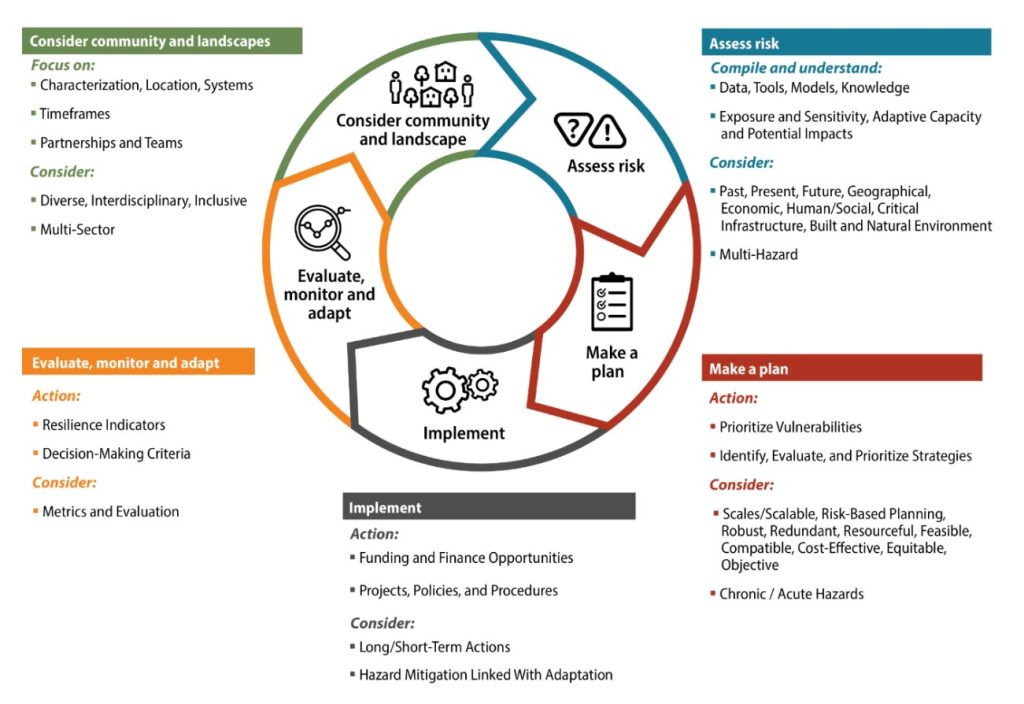

Community adaptation to climate change can be approached at multiple levels and starting points. This Resilience Building Framework provides a framework for taking stock of existing actions and aligning those actions so that a more directed approach to resilience can be charted (Figure 1).7

Resilience building is a continual cycle of various steps from taking stock and visioning at a high level to assessing, planning, and implementing projects (Table 1). Progress is often non-linear, and work can be concurrently accomplished at points along the cycle. Each proposal, project, or plan is an opportunity to ask how climate change can be integrated so communities build resilience incrementally.

Adaptation plans often call for shared solutions across sectors and community members. The path to resilience can be about how decisions are made so that climate is included, and who is at the table when those decisions are made.8 Your work may surround a specific asset that could be made more resilient or an ordinance that can be updated, or it may relate to a planning process that can take stock at a higher level and chart a more resilient future overall. There are also many opportunities in community resilience-building processes to empower additional groups to steward their own visioning and actions that can be an essential component to ensuring more sustainable, equitable outcomes. Overall, each project presents an opportunity, and the Resilience Building Framework can help to clarify essential steps where those opportunities lie to bring about successful, resilient outcomes.

When adapting systems and infrastructure, it is important to draw from the strengths of your town and the skills of local leaders. You can look to neighboring communities to learn about their climate-resilience initiatives. The process requires learning through your work and from peers to constantly improve. This workbook has compiled a starting list of decision support tools, case studies of best practices, and training and networking opportunities from Maine that can support your work in each part of the Resilience Building Framework.

Figure 1. Resilience Building Framework:

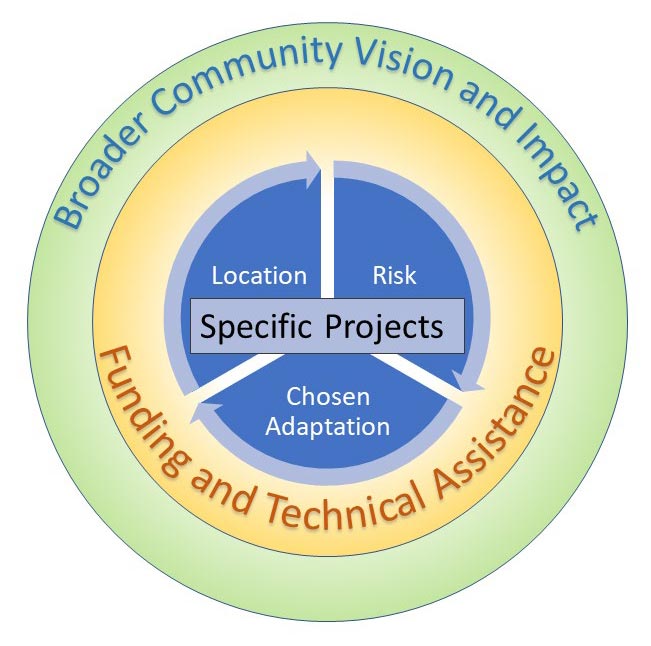

Specific funding opportunities and/or collaborations with climate adaptation specialists may initiate climate resilience efforts, leading to both specific projects and work to build consensus for a broader community vision.

As communities work on climate resilience, the impacts and processes resulting from their efforts will overlap. Communities may initiate a climate adaptation process based on unique circumstances, specific projects, outcomes, and/or priorities. While the workbook follows a linear outline, it acknowledges that this is not always what happens in practice.

Graphic: Cited from the EPA Regional Resilience Toolkit.

4 Definitions pages 109-110 Maine 2020 Climate Change Action Plan, Maine Won’t Wait, December 2020, Maine.gov (PDF).

5 Silka, Linda, Sara Kelemen, and David Hart, 2020. Assessing the Potential Equity Outcomes of Maine’s Climate Action Plan: Framework, Analysis and Recommendations, Senator George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions, September 2020 (PDF) p.6.

6 U.S. Department of Homeland Security. (2016). Resiliency Assessment, Casco Bay Region Climate Change (Casco Bay Estuary Partnership).

7 The Framework was developed by the Maine Climate Change Adaptation Providers Network to aid climate action efforts by providing orientation to a sample process that is informed by best practices identified through a variety of state and regional climate resources. This work continues earlier development within Climate Adaptation and Resilience Planning for New England Communities: First Steps & Next Steps (2016) developed by the NEEFC that presents planning tasks, guidelines and tools, and a suggested approach as an extension of what local governments already do. Report available on the University of Southern Maine Digital Commons website.

8 Sample decision-making criteria are provided in Section 4.8 Resilience Assessment Criteria of the workbook.