Maine Home Garden News — March 2013

- March is the month to . . .

- Columnar Fruit Trees

- Spotted Wing Drosophila: An Interview with Jim Dill, Pest Management Specialist

- A Cumberland County Master Gardener Project: Lois Murphy Kindness Garden, Falmouth

By Richard Brzozowski, Extension Educator, University of Maine Cooperative Extension, Cumberland County, richard.brzozowski@maine.edu.

- Prune your fruit trees. For instructions, see Growing Fruit Trees in Maine — Pruning.

- Evaluate your perennials. Inspecting for breakage, heaving, mouse or vole damage, or winter damage. Do what you can to prune off dead material and broken branches.

- Considering using a cold frame for some plantings this spring. For more information on extending the season, see Bulletin #2752, Extending the Gardening Season.

- Start planning your gardens for 2013. Consider needed changes, garden expansions, garden contractions, moving or transplanting (vegetables, fruits, flowers, etc.).

- Consider keeping a gardening journal for the 2013 growing season. Write at regular intervals what is happening in your yard and gardens. Keep track of rainfall, temperatures, appearance of blossoms, wildlife sightings, storm events, etc. Relatively inexpensive devices are available to help you monitor these items.

- If you start seeds, make an inventory of your supplies and a list of needed supplies. Pour through your seed catalog to determine timing. Refrain from starting seeds too early. Make a plan and stick to it. For more information, see Bulletin #2751, Starting Seeds at Home.

- Visit your local garden center to peruse new products. Think back to the performance of your garden(s) last year. What were the major problems and issues? Prepare for similar problems and issues this year.

- Consider joining a local garden club. Do some research on local clubs by asking friends, garden center personnel or your local librarian.

- Get ready for April and the possibility of planting some frost tolerant crops (seeds or transplants) as soon as the soil is workable.

- Consider buying blueberries or asparagus to support the development of the Maine Master Gardener Program statewide. For more information, see “Grow It Right!” benefit plant sale.

- Visit a local maple sugarhouse. For a sugarhouse near you, see the Maine Maple Producers Association website.

By Dr. Renae Moran, Extension Tree Fruit Specialist, University of Maine Cooperative Extension, rmoran@maine.edu

Fruit trees naturally come in a variety of shapes and growth habits. Some have a wide canopy with a spreading growth habit while others grow in a more upright fashion and have a narrow canopy. Columnar or pillar trees are an extremely upright orientation and many short side branches that grow about one inch in length each year. This growth habit is desirable for its unusual shape and where a narrow space is available for planting. Because this trait is innate rather than being induced by a rootstock, it cannot be transferred by grafting. Several dessert type varieties of apple exist with the columnar habit, but have not been found for dessert type pear, plum, apricot or cherry. However, there are ornamental plum and cherry trees with the columnar habit, but they lack the same fruit quality as dessert plums.

Fruit trees naturally come in a variety of shapes and growth habits. Some have a wide canopy with a spreading growth habit while others grow in a more upright fashion and have a narrow canopy. Columnar or pillar trees are an extremely upright orientation and many short side branches that grow about one inch in length each year. This growth habit is desirable for its unusual shape and where a narrow space is available for planting. Because this trait is innate rather than being induced by a rootstock, it cannot be transferred by grafting. Several dessert type varieties of apple exist with the columnar habit, but have not been found for dessert type pear, plum, apricot or cherry. However, there are ornamental plum and cherry trees with the columnar habit, but they lack the same fruit quality as dessert plums.

Apple trees with the columnar growth habit remain within an area of about four feet, but can grow to a height of about 10 feet. Since the trait is not transferred by grafting, commonly available varieties such as Cortland do not exist with this growth habit. If you desire a particular variety, but also want a small tree, select one that has been grafted to a dwarfing stock such as M.27 or M.9. To keep columnar trees small, plant trees with the varietal graft union about three inches above the soil.

Like apple, peach trees come in different shapes ranging from the standard or spreading habit to the more atypical columnar growth habit. The columnar or “skinny” peach needs five to six feet in width. An intermediate or “upright” type has a canopy spread that is somewhat wider than the columnar, and requires more space, eight to ten feet. Columnar and upright peaches can grow to be tall, 12 to 15 feet, so if you prefer a shorter tree, standard varieties are easier to train to a short stature than columnar trees. Few varieties of columnar peach exist since this trait was only recently introduced into dessert peaches by traditional breeding with an ornamental peach.

True columnar plum and cherry varieties are not yet available. However, some varieties have an upright growth habit with a narrow width. The Vanier plum is one variety with a narrow canopy and showy bloom, as well. Plum and sweet cherry trees can be quite large when fully grown requiring up to 20 feet of space. Where a smaller tree size is desired, select plum trees that are grafted to the semidwarfing rootstock, Krymsk 1, which can dwarf plum trees by 30%. Sweet cherry trees are also available in dwarf and semidwarf sizes. Tart cherry trees are naturally low in vigor and don’t often exceed a space of 15 feet, but upright and columnar growth habits are uncommon in tart cherry.

Columnar fruit trees require full sun and the same care requirements as apple trees in general. In Maine, it is recommended that columnar trees be planted outdoors in the ground instead of in pots or other containers in order to protect the root system from subfreezing temperatures that occur in winter. The roots of fruit trees generally die when the soil temperature drops below 23 ºF, which occurs easily when trees are planted in containers. Because columnar trees lack strong branching, they do not lend themselves to training to a particular shape such as the fan in the case of stone fruit and espalier in the case of apple and pear.

Pros of Columnar Fruit Trees

- Can be grown in small spaces because of its upright form.

- Columnar form may fit nicely into the existing landscape.

- Because of the narrow tree size, managing the tree and picking fruit is relatively easy.

Cons of Columnar Fruit Trees

- Because leafing is typically dense, thorough spraying of foliage can be difficult.

- Tree height can be taller than with standard growth habits.

Spotted Wing Drosophila: An Interview with Jim Dill, Pest Management Specialist

I have heard stories about a terrible fly that destroyed blueberry and raspberry fruit of farmers and gardeners last year in Maine. Can you tell me more about that pest?

Spotted Wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) or SWD is an invasive fruit fly, native to Asia. SWD was first reported on the west coast of the United States in 2008 and has rapidly spread to many of the country’s fruit producing regions, including Maine. In September of 2011, SWD was detected for the first time in Maine with a total of 9 flies being captured in 5 southern Maine traps. In 2012, the first flies were caught in mid-July. By September, between 1,200 and 1,500 flies per trap were being captured in southern Maine with hundreds of flies found in traps as far north as Orono and east to Washington County. SWD are roughly the same size and have the same general appearance as your everyday fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), with the exception of a dark spot near the tip of each wing on SWD males (SWD females do not have spots). Unlike the everyday fruit fly, which typically lay eggs in damaged or overripe fruit; female SWD have a serrated ovipositor allowing them to penetrate and lay eggs in ripening fruit. Each female can lay hundreds of eggs and they can go from egg to adult in under 14 days, making SWD an exceptionally prolific pest. In Maine, populations grow throughout mid to late summer, peaking in early fall.

What is so bad about the fly?

SWD lay their eggs in ripening, marketable fruit, infesting the crop with small, white larvae. One berry can have dozens of fly larvae developing inside. The ability to infest ripening fruit, in conjunction with SWD’s late population buildup make late summer small fruits and fall raspberries quite susceptible. Infested fruit may look fine when harvested, but within 24 hours at room temperature the fruit can be reduced to mush. As a non-native species, SWD in Maine has no natural controls. Currently growers need to spray for the pest approximately every 3 days with either conventional or organic insecticides.

Does the fly affect other plants (fruits, vegetables, flowers, etc.)?

SWD has a wide variety of cultivated small fruit hosts, with raspberries, blackberries, blueberries, and day-neutral strawberries being of particular concern. It can also be a pest in other small fruit crops including grapes, cherries, peaches, and tomatoes (especially the yellow cherry type). It does not appear to attack cranberries or apples (unless apples are overripe). In addition to the multiple cultivated fruit hosts, SWD can also infest wild fruit crops including choke cherries, elderberries, and honeysuckle berries, to name a few.

How do I know if the fly is affecting my small fruit?

Early infestations of SWD can be hard to detect in the field, especially in firmer berries like blueberries. Infested fruit will be soft, prone to collapse, and have little to no shelf-life. In some instances tiny pin-prick sized holes can be seen in infested fruit as the result of egg laying and larval breathing, though they are not always visible and can be extremely difficult to notice.

Do you expect the fly to be just as bad in 2013?

We are anticipating SWD to remain a persistent threat to small fruit crops, as it was in 2012. However, this year’s low winter temperatures with periods of little to no snow cover, as well as periods with large temperature fluctuations may limit the fly’s overwintering capability. This remains to be seen.

What should I do to determine if the fly is present and damaging? When do I start looking for the fly?

SWD has been found in all of our trapping locations in southern, central, and eastern Maine and seems to be widespread in much of the state. We will continue monitoring for SWD in these locations and will be expanding our monitoring efforts north of Orono in 2013. Contact your local Extension staff to find out when, where, and if the flies are being captured in the area of interest to you. In 2012, SWD first began showing up in traps in mid-July, so you should start looking for signs of this pest by the first of July, if not sooner. The use of traps is an important component of monitoring for SWD. Unfortunately, we don’t have commercial or easy to use traps available to the backyard gardener or commercial grower. We are currently researching effective trapping techniques to aid in the identification and monitoring of this emerging pest.

What can I use to control the SWD (organic and synthetic)?

Multiple synthetic insecticides have been shown to effectively control SWD, including malathion (a low toxicity organophosphate), diazinon (also an organophosphate), spinetoram (a spinosyn), as well as a variety of pyrethroids (bifenthrin, fenpropathrin, beta-cyfluthrin, zeta-cypermethrin). Spinosad is an effective organic option.

Is there a link for more information about the SWD?

We are currently researching SWD’s movement and habits in Maine in order to provide the public with pertinent management information, but do not have a fact sheet at this time. We do have two videos regarding SWD:

How to Identify Spotted Wing Drosophila Damage

Defending Against Spotted Wing Drosophila

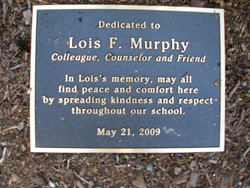

A Cumberland County Master Gardener Project: Lois Murphy Kindness Garden, Falmouth

Katy Gannon-Janelle, Master Gardener from class of 2006, saw a need at the Falmouth Middle School and made it her personal Master Gardener project. The Lois Murphy Kindness Garden began its function as a therapy garden long before it was actually built. Lois was a kind and wonderful guidance counselor at the school who died of cancer, leaving her colleagues and coworkers grief- stricken. Within weeks the school principal had begun to discuss the idea of a statue dedicated to Lois’s memory, to be placed in the school’s courtyard. Lois had been known for her love of flamingos, so that was the form it would take.

Katy Gannon-Janelle, Master Gardener from class of 2006, saw a need at the Falmouth Middle School and made it her personal Master Gardener project. The Lois Murphy Kindness Garden began its function as a therapy garden long before it was actually built. Lois was a kind and wonderful guidance counselor at the school who died of cancer, leaving her colleagues and coworkers grief- stricken. Within weeks the school principal had begun to discuss the idea of a statue dedicated to Lois’s memory, to be placed in the school’s courtyard. Lois had been known for her love of flamingos, so that was the form it would take.

It did not take long for Katy and the staff at the school to determine that the statue could not stand alone on the grass, but would need a surrounding garden for context. The planning of that garden over the first year after Lois’s passing was to serve as a form of therapy for those who knew and loved her. It was very easy to recruit volunteers. Her former coworkers were the most ready. They needed a project to get their hands, and in some cases money, into. It was a way to deal with the loss.

The process of planting a garden within a courtyard was not an easy one. Katy headed up the project putting together a finished design and the Master Gardener Volunteers began the task of amending the soil with literally truckloads of loam and compost, which they wheel barrowed in through the halls of the school. Twenty Master Gardeners from Cumberland County embraced the project and supported Katy in construction, planting trees and adding perennials and annuals. A strict planting list was distributed to all involved, so as to tamp down enthusiasm to just dig and divide anything and everything folks could get their hands on. The garden had a strict plan, and color focus in the flamingo shades, of course.

The process of planting a garden within a courtyard was not an easy one. Katy headed up the project putting together a finished design and the Master Gardener Volunteers began the task of amending the soil with literally truckloads of loam and compost, which they wheel barrowed in through the halls of the school. Twenty Master Gardeners from Cumberland County embraced the project and supported Katy in construction, planting trees and adding perennials and annuals. A strict planting list was distributed to all involved, so as to tamp down enthusiasm to just dig and divide anything and everything folks could get their hands on. The garden had a strict plan, and color focus in the flamingo shades, of course.

On the one-year anniversary of Lois’s death, the garden was opened in a touching ceremony attended by students, faculty, parents, Master Gardeners, and Lois’s own family and friends. The space continues its role as a therapy center in the school. It is an oasis of quiet and beauty offered to a student population not often given credit for appreciating such things, but clearly doing so. Art classes and science classes use the space for curriculum. Students are rewarded for good behavior with the invitation to bring a friend and lunch out there amidst the blooms. The guidance department overlooks the space, meeting sometimes with new students and their families in this wonderful courtyard.

On the one-year anniversary of Lois’s death, the garden was opened in a touching ceremony attended by students, faculty, parents, Master Gardeners, and Lois’s own family and friends. The space continues its role as a therapy center in the school. It is an oasis of quiet and beauty offered to a student population not often given credit for appreciating such things, but clearly doing so. Art classes and science classes use the space for curriculum. Students are rewarded for good behavior with the invitation to bring a friend and lunch out there amidst the blooms. The guidance department overlooks the space, meeting sometimes with new students and their families in this wonderful courtyard.

Volunteers from St. Mary’s Garden Club, the faculty and staff at the school, and Falmouth Middle School students of the Green Team maintain the space today along with Master Gardeners throughout the gardening year and on scheduled workdays in the spring. “We all feel the presence of another pair of hands nurturing there. Pansies, Lois’s favorite flower, self sows, multiplies, and blooms for a longer season than seems climactically possible. We all have our theories,” says Katy.

This project welcomes new volunteers. Call the University of Maine Cooperative Extension Cumberland County Office at 207.781.6099 or 800.287.1471 (in Maine) if you are interested.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications fill out our online form.

Contact Lois Elwell at lois.elwell@maine.edu or 1.800.287.1471 (in Maine).

Visit our Archives to see past issues.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around Maine, with Professor Richard Brzozowski serving as editor.

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2013

Published and distributed in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of Congress of May 8 and June 30, 1914, by the University of Maine and the U.S. Department of Agriculture cooperating. Cooperative Extension and other agencies of the USDA provide equal opportunities in programs and employment.

Call 800.287.0274 or TDD 800.287.8957 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.