Maine Home Garden News – June 2024

In This Issue:

- June Is the Month to . . .

- The Magic of McAlpin

- Making the Most of Volunteer Plants

- When Summer comes to the Land of the People of the Dawn

- Ask the Expert: I’ve heard PFAS is found in carboard. Is it safe to use it in the garden?

- Backyard Bird of the Month: Blackburnian Warbler

- Join the Search for Emerald Ash Borer

- Mainely Dish: Spinach-Rice Casserole

- Climate and Weather Update

June Is the Month to . . .

By Dixie Turner, Ph.D. Penobscot County Master Gardener Volunteer

- Stay ahead of weeds in your garden. Small weeds are much easier to control than large ones! Small weeds can easily be pulled or hoed and left to dry on the soil surface. Make

sure you keep weeds from going to seed to prevent problems next year! Regular efforts make a big difference. Tilling, hand pulling, clipping, and mulching are sound weed control strategies. For garden weeds, see Rutger’s weed gallery.

sure you keep weeds from going to seed to prevent problems next year! Regular efforts make a big difference. Tilling, hand pulling, clipping, and mulching are sound weed control strategies. For garden weeds, see Rutger’s weed gallery. - Check for insect pest damage to your plants by making “walk throughs” each week. Look for leaf, stem, and blossom damage. Check the undersides of leaves for egg masses. Visit UMaine Extension’s Insect Pests, Plant Diseases & Pesticide Safety website for facts sheets about common insect pests in Maine. Submit an Insect Specimen for free identification and diagnostic help. Consider Integrated Pest Management (IPM) when you have a pest management issue.

- Use organic mulches to control weeds and maintain soil moisture. Compost, bark, wood chips, straw (not hay), shredded leaves, and pine needles all can work well in a variety of landscape settings, but should not be at a depth of more than 2” and not in direct contact with the stems of woody plants. Placing a few layers of wet newspaper down prior to adding organic mulches can help provide a good extra barrier for weed suppression.

- Assist a neighbor who may have difficulty gardening to physical limitations or illness. Even helping them plant an herb garden can make a big difference in the life of a former gardener.

- Be aware of the threat of ticks. Check your family and pets for ticks daily. Learn more about ticks at University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Tick ID Lab.

- Visit a pick-your-own strawberry operation to find the ripest berries of the season. You can find a farm on the Get Real Get Maine website. When you get home, enjoy your berries fresh or preserve them by freezing or making jam. Learn more in Bulletin #4036, Let’s Preserve Berries and Bulletin #4039, Let’s Preserve Jellies, Jams, and Spreads.

- Keep an eye on rainfall amounts with a rain gauge. Most annual crops and newly planted perennials (woody and herbaceous) do best with 1 to 1.5 inches of rain per week.

- Reduce waste by composting grass clippings, leaves, and kitchen scraps. For more information, check out our Home Composting

- Dead head flowers to help them flower throughout the summer.

- Finish planting your cold-susceptible transplants like tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, cucumbers, and squash and start harvesting your early crops like lettuce, spinach, etc.

The Magic of McAlpin

Behind the scenes in the greenhouse that connects the historic lands and gardens of Mount Desert Island

By Clarisa Diaz, Writer and seasonal gardener at McAlpin Farm

Every summer, thousands of visitors admire the beautifully kept gardens of the Mount Desert Island Land and Garden Preserve. The Azalea Asticou Garden offers a Japanese-inspired

meditative and meticulously manicured landscape, while the Thuya Garden offers an array of native and ornamental pollinator-attracting flowers and plants in an intimate space behind a rustic lodge. The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden, the largest of the Preserve’s gardens, is only open in July and August and has winding paths through various breathtaking garden designs.

But few visitors know that many of the plants they immerse themselves in are grown at McAlpin Farm, a series of connected temperature-controlled greenhouses with a cut flower farm and holding spaces for hardy plants during the off-season. The Seal Harbor nursery for the gardens is not open to the public. The farm’s small staff works tirelessly to raise thousands of flowers, shrubs, and grasses—many from seed and cuttings—through the winter and spring months. The planning and production of plants for distribution across the island is impressive, especially since it’s all done using sustainable practices. The gardeners of the McAlpin wash and reuse pots and trays to reduce plastic waste, compost stock plants and other green waste for the farm, and use beneficial insects for pest control instead of relying on pesticides. Here’s a behind-the-scenes look at some of these practices and how McAlpin’s gardens make plant magic happen year after year.

Germination, propagation, and lots of potting

McAlpin’s full-time staff include Brenna Sellars who focuses on seed germination and Megan Stillman who propagates plants from cuttings. Cassie Banning, Director of Farm and Gardens, oversees this work and manages the ebbs and flows of McAlpin—coordinating with all the garden managers on which plants to grow for the next season’s garden designs. McAlpin staff is supported by help from all Gardens staff, seasonal gardeners, and volunteers, who make a team that transplants and pots thousands of seedlings—over 13,000 of which are annuals. Native and perennial plants are grown from seed, taking years before they can go out to the gardens or lands. “Plants are being grown or stored all year long. This week I started 50 trays of annual seeds and next week I’ll start another 30. It’s hard to fathom how many plants we grow and how many are in the gardens,” said Sellars. In addition to the gardens, McAlpin grows over 2,000 native plants for Thuya’s woodlands and 700 plants for the Preserve’s Natural Lands.

“One of the things I love is that even though you’re doing similar things each season, it’s always going to change a little bit because of weather and which plants we’re growing. There’s always a shift and change. You always have to wrap your head around the new thing. This job allows for so much experimentation.”

While Sellars seeds, Stillman cuts. “This is the last batch of cuttings, it’s very exciting. This is a ‘Mulberry Jam’ Salvia, it’s got beautiful magenta flowers,” explained Stillman. McAlpin maintains stock annual plants that are grown specifically to take cuts from, the cuttings becoming the next generation of plants. Certain types of heliotropes, like ‘Royal Fragrance’

Heliotrope and Old Fashioned, as well as ‘Double Azalea Apricot’ Snapdragons are no longer found on the market and must be maintained each year from cuttings. “In the winter we keep a succession of stock plants going and try to time them so that they’re ready for the new season.”

Potting happens nonstop at McAlpin. Transplanted seedlings and plugs are placed into bigger and bigger pots, eventually filling all the greenhouses by late spring. Soil depth, moisture, and compaction are all key in getting a plant rooted properly. Repetition builds consistency leading to similar growth across plants. Each tray of plants and plants in larger individual pots must be labeled as they move positions and get reorganized to make space as the summer approaches.

A clean greenhouse makes healthy plants

The greenhouse is a beautiful and peaceful place, filled with seedlings and hardy green plants. This healthy environment is made so because of attention to cleaning the greenhouse on a weekly basis. Well-swept floors and potting benches keep pests and diseases at bay. Used pots are washed to be sanitized and reused, a huge undertaking in itself. “A lot of greenhouses and nurseries will just throw away their pots every year,” explained Sellars. “We’ve switched over to primarily using a lot of fiber pots, which can be composted, but certain plants don’t do well in fiber pots because they tend to dry out faster. So we wash and sanitize all of our plastic pots.” In addition to the compostable pots, this amounts to thousands of pots and trays that are deep-clean sanitized at least once per year and reused every season. The inside of the

greenhouse is thoroughly sanitized after all plants are distributed to the gardens in the early summer.

Integrated pest management is also practiced at McAlpin. Predatory insects and mites, such as those found in Thripex, Spidex, and Enermix, control and prevent thrip and whitefly populations in the greenhouse. “Once you get whiteflies, they’re harder to get rid of. We have a constant every other week input of predator wasps as a preventative,” said Sellars.

Both Sellars and Stillman think of McAlpin as a unique place to experiment and thrive. “We get to experiment with all kinds of different plants: we grow annuals, we grow perennials, and natives—it’s the best of all gardening,” said Stillman. Because McAlpin is a greenhouse solely for the Land and Garden Preserve, the objective for growing plants is not profit but pure enjoyment. “We’re not just trying to fill the greenhouse with crazy amounts of one type of plant. We get to actually know these plants and take care of them. It’s wild to see these plants when they’re little and what they become in the gardens.”

From a new seasonal gardener perspective, it is certainly an eye-opening experience to see the planning and operations behind making the Preserve’s gardens what they are each summer. Details one would never think about when simply looking at a flower in bloom—the care and thought behind each plant since its infancy is to be admired with so much more to learn.

Making the Most of Volunteer Plants

By Naomi Jacobs, Penobscot County Master Gardener Volunteer

One of the great pleasures of gardening is witnessing plants’ willingness to grow. Given enough water and the right light and soil, most will do their magic trick of turning sunshine into flowers and food. We often see this desire to thrive and replicate in the form of volunteer (self-propagated) plants that pop up in unexpected places ranging from cultivated flower beds to cracks in parking lot pavement.

Both food and flower gardeners can take advantage of volunteers. They can spare us the trouble of sowing and might give us an earlier start, too. In the cottage garden, self-seeded plants contribute to a relaxed style and collaborate with the garden designer on interesting color combinations. But like human volunteers, these plants don’t always pop up in the places where their virtues can shine. They need management to flourish. With a little foresight, care, and reasonable expectations, we can make the most of these little surprises.

Edible plants

Volunteer seedlings in our edible gardens are tricky because of three main issues:

- The progeny of cultivated (aka hybrid or F1) varieties will not necessarily have the same traits as the parent plant.

- Cross-pollination can also result in the next generation having unexpected traits. This is especially true for members of the Cucurbitaceae family (squash, pumpkins, and cukes), which cross-pollinate easily. Fruits resulting from the pollen from one type fertilizing the female flower of a different type will look normal, but the seeds (and later volunteer seedlings) will have the mixture of traits from the two different parent plants.

- Some diseases, such as late blight, can survive on overwintered seeds or tubers. Similarly, that potato from the grocery store that sprouted in your compost bin can’t be guaranteed as disease free. Always start potatoes from certified disease-free planting stock and cull out any that have overwintered.

For these reasons, we don’t recommend transplanting or keeping most volunteer vegetables. If you do want to give them a chance, be prepared to see surprises and potentially unfavorable characteristics such as a different taste, appearance, or delayed ripening time. Such variability is less of an issue with open-pollinated or self-pollinated seeds, which are more likely to come true to type.

Self-seeded greens and herbs are less likely to show problems with disease. Again, they might lose some of their desirable features if they are from a hybrid parent or the result of cross-pollination. Many common annual greens such as lettuce, arugula, and mustard are happy to self-seed for next year and may even produce a second crop in their first year. The same is true for annual herbs like dill, cilantro, and chamomile. If you want to encourage leafy plants to seed, don’t harvest the leaves after the plants bolt. This will encourage the plants to go to seed more quickly. Let the dried seeds drop in place or simply sprinkle them where you want them to grow.

Ornamental plants

Many beloved flowering plants will happily volunteer in the home garden just as they do in the wild. While, like vegetables, they can cross-pollinate, the resulting variations are often delightful rather than problematic. The basic principle of management is to learn to recognize the seedlings, to transplant those you have a place for, to watch for crosses or plant combinations that you particularly like, and to rogue out the ones you don’t like or that are getting crowded.

In recent years, we’ve learned to leave the seedheads on native perennials over winter, to provide food for the birds. The resulting seedlings sometimes threaten to get out of hand, but with a little forethought and management, they bring a wonderful element of serendipity to the flower garden. They tend to prefer sun or part sun, but a few noted below will also establish themselves in shade. Most are relatively compact and not deep-rooted. Easy to move or remove, they intermingle nicely with other plants.

Some stay quite true to type while others cross-pollinate freely, generating a range of shades and forms. To integrate these plants into your garden, mark the best specimens (bread bag tags work well) and let them go to seed where they are; or collect the dried seed heads to start new plants elsewhere. Simply sprinkle the seeds where you want them and let nature do its work. Discourage ones you don’t like by cutting off the stems before they go to seed or pulling up the plants entirely as soon as bloom has ended.

The following is a short list of some of the many ornamentals that commonly self-seed and are not difficult to control.

- Alchemilla mollis (lady’s mantle)—This unique foliage plant offers airy yellow blooms that serve well as a cut flower. It’s a natural fit for the front of a border garden.

- Aquilegia (columbine)—Columbine comes in white, yellow, blue, pink, and red, depending on the parentage. It’s a good choice for dappled shade as it can handle competition from tree roots. Some of mine have seeded up against the trunk of a recently removed mature Norway maple where little else will grow.

- Aruncus dioicus (goat’s beard)—Displays of large feathery white plumes can be seen in June. Goat’s beard can get as big as a shrub and performs well in poor soil and part shade.

- Dianthus carthusianorum (Carthusian pink)—This charming dianthus presents little hot pink flowers atop slender, flexible stems.

- Digitalis lutea (yellow foxglove)—This is an excellent self-sower in partially shaded sites and offers a soft shade that complements many other colors. Yellow foxglove will sometimes rebloom if spent stalks are removed.

Yellow foxglove (center) and lady’s mantle (back left) volunteers happily growing in the author’s perennial border. - Echinacea (purple coneflower)—Coneflowers will usually revert to species if the seed parent is a hybrid.

- Echinops (globe thistle)—This plant with its interesting form and spiky gray foliage is usually listed as needing full sun, but it will volunteer and bloom even in dappled shade.

- Liatris spicata (blazing star or prairie gayfeather)—This native comes in purple or white. Finches love the dried seed heads.

- Lychnis coronaria (rose campion)—White or hot pink with soft gray foliage. Blooms best in sun but adapts to a range of conditions and will even start itself in poor, dry soil.

- Matricaria (feverfew)—This plant is a short-lived perennial with white flowers and low, bushy form.

- Orlaya grandiflora (white lace orlaya)—This delicate-looking early white cut flower is sturdier than it looks. Seeds readily in sunny, well-drained soil.

- Papaver (annual poppies)—Shake one of the “pepper pot” seed heads over your beds in the fall for a big treat the following year. In May, your only task will be to thin out the hundreds of seedlings that appear. These do not transplant well, so be sure to scatter the seeds where they’ll be enjoyed if you’d like to see them beyond where they’re currently growing.

- Penstemon (beardtongue)—Choose carefully since some enticing members of this family sold in local stores aren’t hardy in Maine. “Husker Red” has good longevity and consistency. It features purple foliage and stems, with stalks of pale pink flowers.

- Rudbeckia (black-eyed or brown-eyed Susan)—Seedlings look much like echinacea seedlings; seedheads overwinter well. The biennial form, sometimes sold as “Gloriosa Daisy,” has a fuzzy leaf. It is not long-lived, but seeds reliably and provides excellent late-season color over a long period.

- Verbena bonariensis (tall verbena)—This attractive late-season plant has never self-seeded for me, but many people say they can’t get rid of it!

- Viola (Johnny jump-up, wild pansy)—Charming flower like a small pansy. Blooms in May. Edible.

Recognizing volunteers

You may be wondering “how do I know if it’s a volunteer or a weed?” Recordkeeping or photos of prior gardens can help with identifying mystery seedlings that may have redeeming

qualities.

If you’re noticing a lot of one type of seedling in a particular area, noting what grew there in the past might be just the hint you need to determine if it’s a friend or foe.

Transplanting

If you need to move volunteer seedlings, follow these tips to minimize transplant shock and enhance your chances for success:

- Transplant volunteer seedlings when they are very small (ideally with only 1-2 sets of true leaves).

- Loosen the area around the seedling and gently handle seedlings by their roots and leaves, not by the stem.

- Move plants on an overcast or rainy day and, if planting directly into another garden, try to time it when the following days are also expected to be overcast or rainy.

- If you don’t immediately have a place for the seedlings, plant them in a flat or pots and hold them in a protected spot until the space is ready.

When Summer Comes to the Land of the People of the Dawn

By Lynne Holland, Horticulture Professional, University of Maine Cooperative Extension

Summer has always been a time for gathering. The people in this place we call Maine used this time to travel and trade. These gatherings always included storytelling. One such story is the summer legend. This modern interpretation of an ancient story has many themes running through it about people, plants, animals, and movement.

One such tale is that of Glooscap bringing summer to the land that we now call Maine. The full story of a long journey and how Summer overcame Winter, a worthy read, can be found on the Cedar Circle Farm and Education Center website. Most ancient societies recognized the summer solstice as a time of fertility and growth. In many areas, the change in the length of daylight is not nearly as dramatic as it is in Maine. But, as gardeners, this lengthening of days is a signal to plant certain crops and a signal to certain crops to change the direction of their growth, (think long-day onions bulbing and strawberries setting runners rather than fruit).

The long cool spring in the northeastern US often makes for uncertainty due to the weather. Bright warm days can be followed by frost or cold wet nights. There are many memes about false spring and second winter, but once the solstice happens, it is truly summer in Maine. In nature many flowering plants are more affected by the length of day than by temperature for blooming. These changes remind us of the magic and movement that organize our movements in the summer. The stories of Glooscap provide guidance to these movements.

In one story, Glooscap hears from the Loon about a land that is far away and always warm. Though a medium-distance migrator, the movement of the loons is a signal of the change from winter to summer and vice versa in the fall. Also in the story, Glooscap rides a whale to this warmer place and then allows the whale to go back to the open sea and colder northern feeding grounds. This migration north has long been known about whales and is the basis for whale-watching trips out of many coastal towns. So many creatures have started “moving again” on both land and sea by that longest day of the year, including the tourists that come to “Vacationland” and those who head “upta camp.”

The summer legend describes Winter as a pipe-smoking charmer who puts the land to sleep, and Summer is a brown-haired maiden with a floral crown who wakes the world and greens up all the plants. In Western Europe, the solstice is connected to stone circles like Stonehenge, and at the UMaine Extension, the lengthening days mean an uptick in calls and questions from gardeners. There are many different ways of seeing these signs of the season and that change has come to the land. On the coast, the running of the alewives is common where dams have been removed and fish ladder festivals where there are still obstructions. People gather to harvest with “pick-your-own” signs popping up for strawberries, raspberries, and blueberries. Food and fruit-themed fairs and festivals mark nearly every weekend starting at the end of June with strawberries, then moving on to clams, lobster, and blueberries (and that is just in July!). It is truly a part of this land for people to gather around nature and bounty during these longer, warmer months.

The lesson in the end is that Summer leaves the area far to the north of Glooscap’s region to Winter, and she only stays for six months each year. Although Summer is more powerful than Winter, she also recognizes the need for the world to rest. And so it is with many gardeners: working frenziedly in the spring and early summer and then gradually slowing down as the days start to shorten again.

Editorial note: how to share it Help Centre (ONF NFB)

Ask the Expert: I’ve heard PFAS is found in cardboard. Is it safe to use it in the garden?

By Caragh Fitzgerald, Associate Extension Professor

PFAS stands for “per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances.” PFAS are a family of synthetic chemicals used to make heat-, water-, stain-, and grease-resistant products. PFAS have been used in products since the 1950s and are still used today. We encounter PFAS in products such as nonstick cookware, outdoor clothing, paper plates, dental floss, stain-resistant carpets, and firefighting foam.

We do know that many cardboards and papers that are designed for food contain some amount of PFAS to make the packaging grease- and water-resistant. So, it is better to not use these materials in a home garden.

There is little information available about the amount of PFAS in clean, corrugated cardboard. So, we can’t say if there is a risk to using it in the garden. Plain, corrugated cardboard generally isn’t expected to be water- or grease-resistant, so it likely contains less PFAS. Any PFAS in the cardboard would be diluted by the much larger volume of the existing soil and any other amendments. (Remember to remove tape and stickers from these products before using them in the garden.)

The UMaine Extension fact sheet, “Understanding PFAS and Your Home Garden,” outlines some of the conditions that would likely increase PFAS levels in the soil, depending on application rates and concentrations. These include the following:

- farmland with a history of sewage sludge application that was converted into residential lots with gardens

- topsoil obtained from farmland with a history of sludge application

- use of soil amendments containing sewage sludge (“biosolids”) containing PFAS or manure from animals fed PFAS-contaminated feed or water

- irrigation with water from a source that contains PFAS

Learning more about the history of your land and the soil amendments used on it can help you decide if testing your soil for PFAS would be worthwhile. This testing must be done very carefully to prevent contamination and it is expensive. For more information about soil testing for PFAS, please see the Maine Department of Environmental Protection’s publication “A Homeowner’s Guide to Soil Sampling for PFAS.”

As of spring 2024, early research indicates that lettuce and spinach take up more PFAS than some other vegetables, such as green beans, potatoes, and asparagus. There is still much research to be done on vegetable crops, though, so it is best to check for most current recommendations.

Lastly, consider what you grow and how much produce you consume from your garden. If your garden is small, potential PFAS contributions from your home-grown produce may be very small compared to PFAS from other sources in your life.

If you have further questions, please email extension.pfasquestions@maine.edu.

Backyard Bird of the Month: Blackburnian Warbler

By Andy Kapinos, Maine Audubon Field Naturalist

If there are spruce, fir, or hemlock trees around your backyard, listen carefully for the high-pitched, buzzy song of the Blackburnian Warbler. While they can be difficult to see, often hidden among foliage high in the canopy, and share habitat with several closely related species like Black-throated Green and Magnolia Warblers, there is no mistaking a Blackburnian Warbler when you see it. They are the only warbler seen in Maine with an orange thBackyard Bird of the Month: Blackburnian Warblerroat, which stands out against a black cap, cheek, back, and wing.

The name for this bird in Puerto Rican Spanish, reinita de fuego, translates to “fire warbler,” which accurately describes the shockingly ember-like plumage of the Blackburnian Warbler. In most other dialects of Spanish and French, the bird is called the equivalent of Orange-throated Warbler. The English name was chosen by naturalist Thomas Pennant to honor English botanist Anna Blackburne and is one of the eponymous bird names that will be changed by the American Ornithological Society in the coming years, perhaps to Orange-throated Warbler. Whatever you call it, these are some of the most spectacular warblers seen in Maine, and they nest throughout the entire state, generally in the tops of coniferous trees. They actively forage there for insects, mostly moths and their larvae, like spruce budworm species. In the fall, they migrate from the boreal and northern hardwood forests to the slopes of the northern Andes, especially in Colombia, where they also feed on insects in tree canopies. They are yet another species that demonstrates the need to conserve forest habitats and native trees throughout the Americas, in addition to our own backyards!

Join the Search for Emerald Ash Borer

By Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry

Six years ago this week, emerald ash borer (EAB) was found in Edmundston, New Brunswick. Soon after, Maine crews found the edges of that infestation along the Saint John River in Madawaska. Now, EAB is known in seven of Maine’s sixteen counties.

You can be part of the team that is looking for EAB populations in Maine. Whether you become informed about what to look for and then look for signs of attack as you travel the state or you join the survey through girdling an ash tree or monitoring a colony of native, buprestid hunting wasps (known as the “beetle bandits”), when you engage in the search, you improve our response to this insect.

Spot the signs

Visit our website or watch a webinar to learn the signs of an EAB attack. Once you know the signs and recognize ash trees, you can be part of our detection network. Ash trees are abundant in the places we do business (once you can recognize this tree, you’ll be surprised how often they were planted). They line our roadways and rivers and are scattered within our forests. Keep tabs on them, and report signs of attack.

Set a trap

If you own or manage land with ash trees in Maine outside where EAB has already been found, you could become an important part of our detection network. Volunteers participating in our EAB trap tree network have made meaningful contributions to our knowledge of where the insect has landed. In particular, we want to know where EAB has spread, so if your property with ash is in a noninfested area of the quarantine zone (blue) or potentially infested area (orange), you can help us out. Learn more about this program!

Watch the wasps

If you can’t get enough of the wonders of nature, then wasp watching may be your next passion. The “beetle bandit,” Cerceris fumipennis, is a native, solitary soil-dwelling wasp. It hunts beetles in the Buprestidae family to provision its nests. When EAB is an area, these wasps are a good detection tool for this pest. If you can spend some time on warm, sunny days in July and August looking for these colonies or monitoring what the wasps are returning with, we can use your help as a wasp watcher. Important note: these wasps are safe to handle.

Explore more

Explore more

EAB was the catalyst for awareness of the risks to our forests from transported firewood. The list of devastating pests that have hitched a ride in or on firewood has grown in the last two decades. You make a difference in the spread of EAB and other forest pests and the future of our forests when you make choices about firewood.

Here’s what YOU can do to make a positive difference:

- Explore the resources on our website for information about monitoring and managing ash, recognizing EAB damage and more.

- Visit the website and sign up for the newsletter at the Ash Protection Collaboration Across Wabanakik (APCAW) to learn about efforts to sustain ash in the region.

- Realize the threat: Untreated firewood moved more than 10 miles puts our trees and forests at risk!

- Be responsible: Choose only local or certified heat-treated firewood. Protect our forests from these hidden dangers.

- Source locally: When camping or enjoying the great outdoors, support local vendors offering safe, affordable, locally sourced firewood. Check out firewoodscout.org for options!

Mainely Dish: Spinach-Rice Casserole

By Alex Gayton, Assistant EFNEP Coordinator & Social Media Coordinator, Expanded Food Nutrition and Education Program (EFNEP), University of Maine Cooperative Extension

April 1, 2024 Recipes, Spoonful

Education Program (EFNEP), University of Maine Cooperative Extension

Visit EFNEP’s recipe website for the Spinach-Rice Casserole recipe and recipe video.

Casserole recipes are great because usually all you have to do is combine the ingredients in a casserole dish or baking pan and then put it in the oven to bake. This Spinach-Rice Casserole is filling and easy to make. Writing this blog inspired me to make this recipe again, so I decided to add it to my lunch meal plan this week. I used the kale I had frozen last fall and was able to make this dish quickly on Sunday night for lunch on Monday. I will admit, I didn’t plan ahead and had to wait for the rice to cook, but while the rice was cooking, I prepped the rest of the ingredients, so everything was ready to go when the rice was done. This recipe is composed of simple ingredients and it’s quick to prepare. I had all the items on hand for this casserole, so I didn’t need to shop for anything. The casserole takes on the flavor of the leafy greens you choose. I prefer the taste of spinach over kale, so I will plan to use spinach next time or try a new leafy green like bok choy or Swiss chard because I haven’t tried those greens yet. My daughter and husband smelled the butter, onion, and garlic cooking and were immediately interested in what I was making, it did smell great!

If you don’t cook rice very often you might find this helpful. In general, 1 cup of uncooked rice will make about 3 cups of cooked rice. For this recipe (and to keep the math simple), I recommend cooking 2 cups of uncooked rice to equal about 6 cups of cooked rice and freezing the extra in a freezer-grade container or zip-top bag for future use. The amount of liquid required can change depending on the rice you use, so refer to the rice package or read the recommendations in this article All About Cooking Rice (University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension).

Resources

- All About Cooking Rice (University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension

- Spinach-Rice Casserole Recipe Website

Maine Weather and Climate Overview (June 2024)

By Dr. Sean Birkel, Assistant Extension Professor, Maine State Climatologist, Climate Change Institute, Cooperative Extension University of Maine

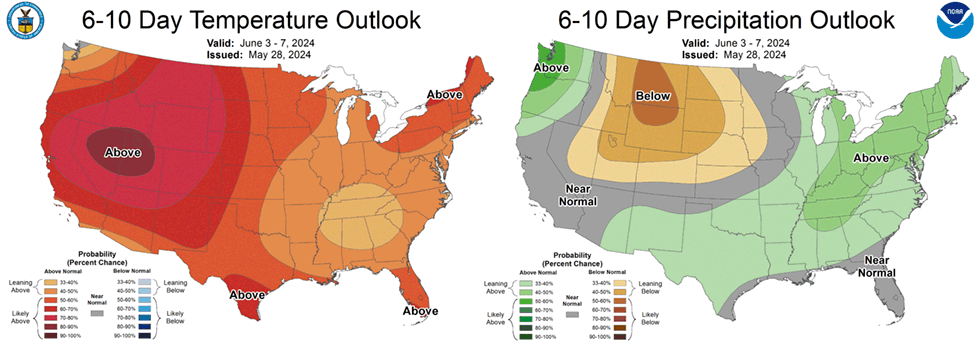

Maine statewide temperature and precipitation data from NOAA show that April 2024 ranks 23rd warmest (top 1/3) and 45th driest (normal) for records beginning 1895. Statewide monthly means for May are not yet available, but May 1–29 temperature rankings for observations in Bangor, Caribou, and Portland are 6th, 3rd, and 14th warmest, respectively. May precipitation has been below normal across most areas, but near normal west of Penobscot Bay and around Bangor, and in some parts of western Maine. As shown on the Northeast Drought Early Warning System, cumulative precipitation deficits in April and May have led to below or much below normal streamflows across much of the state. Most groundwater observation sites show near normal levels, whereas some show signs of hydrologic drought. Rainfall and cloud cover have been sufficient to maintain near normal soil moisture for most of the state. The U.S. Drought Monitor depicts abnormal dryness across northwestern Aroostook County, and there is potential for this to expand in the next week, depending on rainfall. To that point, the current weather forecast through the start of June shows dry weather. Both the 6–10 day and 3-4 week climate outlooks (see below) show above normal temperature and a lean towards above normal precipitation. Be sure to check the latest forecast for your area at weather.gov.

| Product | Temperature | Precipitation |

|---|---|---|

| Days 6-10: June 3-7 (issued May 28) | above normal | above normal |

| Weeks 3-4: June 6-19 (issued May 24) | above normal | above normal |

| Seasonal: June, July, August (issued May 16) | above normal | equal chance |

For additional climate and weather information, including historical temperature and precipitation data, visit the Maine Climate Office website.

For questions about climate and weather, please contact the Maine Climate Office.

Do you appreciate the work we are doing?

Consider making a contribution to the Maine Master Gardener Development Fund. Your dollars will support and expand Master Gardener Volunteer community outreach across Maine.

Your feedback is important to us!

We appreciate your feedback and ideas for future Maine Home Garden News topics. We look forward to sharing new information and inspiration in future issues.

Subscribe to Maine Home Garden News

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications, click on the Subscribe button below.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

For more information or questions, contact Kate Garland at katherine.garland@maine.edu or 1.800.287.1485 (in Maine).

Visit our Archives to see past issues.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around Maine. The following staff and volunteer team take great care editing content, designing the web and email platforms, maintaining email lists, and getting hard copies mailed to those who don’t have access to the internet: Abby Zelz*, Annika Schmidt*, Barbara Harrity*, Kate Garland, Mary Michaud, Michelle Snowden, Naomi Jacobs*, Phoebe Call*, and Wendy Robertson.

*Master Gardener Volunteers

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2023

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.