Maine Home Garden News — February 2024

In This Issue:

- February Is the Month to . . .

- Growing Microgreens

- Licensing Requirements for Arborists in Maine

- Help Track Forest Pests This Winter

- Backyard Bird: Golden-crowned Kinglet

- Ash Protection Collaboration Across Wabanakik (APCAW)

- Book Review: A Northern Gardener’s Guide to Native Plants and Pollinators

- Maine Weather and Climate Overview (February 2024)

- Winter Interest

February Is the Month to . . .

By Barbara Harrity, Penobscot County Master Gardener Volunteer

Order seeds and gather seed starting supplies.

Order seeds and gather seed starting supplies.

If you haven’t already ordered seeds, don’t delay! Many items are already back-ordered or fully sold out for the season.

Sign up for a webinar.

Our three-part spring webinar series includes these enticing topics: Home Grown Cranberries; Harvesting Hidden Gems: Practical Insights for Growing Potatoes and Sweet Potatoes; and Backyard Blueberry Growing Tips from UMaine Experts. Those who register can watch live or enjoy a recording after the session. Our on-demand webinars are also a terrific learning opportunity.

Order bare-root trees and shrubs.

To learn more about the benefits of planting bare-root trees and shrubs, check out “What’s to Love About Bare-Root Plants?” Bare-root plants are resilient and less expensive than container plants of comparable size. However, they’re only available to order in the winter and spring months.

Start geranium, snapdragon, onions, shallots, leeks, and petunia seeds indoors.

Start geranium, snapdragon, onions, shallots, leeks, and petunia seeds indoors.

But wait several weeks before planting other seeds. See Bulletin #2751, Starting Seeds at Home for a helpful chart, and watch for reminders on when to start other seeds in future issues of the Maine Home Garden News. Sowing too early wastes energy and often leads to crowding, disease, insect pressure, and lanky plants.

Replace aging fluorescent bulbs in your grow light fixtures.

Even if they haven’t gone fully dark, replacing older fluorescent bulbs can greatly enhance the quantity of light and lead to more robust seedlings.

Take care of yourself now so you can take care of your garden this spring.

It’s important to prepare your body for the hard physical work of gardening. Regular stretching and some aerobic exercises can make a big difference in how you feel when the season kicks off.

Engage in some armchair garden-related travel.

February in Maine can be gray and cold and make us long for warmer weather or brighter colors. So it’s an ideal time to check out books, websites, or videos that can transport us elsewhere. Here are a few gardening resources that might do just that:

- American Roots: Lessons and Inspiration from the Designers Reimagining Our Home Gardens by Nick McCullough, Allison McCullough, Teresa Woodard (Timber Press, 2022)—available through interlibrary loan from Maine public libraries.

- The Cottage Garden by Claus Dalby (Cool Spring Press, 2023)—available through interlibrary loan from Maine public libraries.

- Virtual tour of the US Botanic Garden. I find the tour of the conservatory particularly soothing, and orchid lovers will enjoy the 14 short videos from the 2020 Orchid Show available on the website.

- Brooklyn Botanic Garden’s Cherry Esplanade tour will brighten your day with dazzling pinks.

Growing Microgreens

By Pamela Hargest, Horticulture Professional UMaine Extension Cumberland County

In the dead of winter, many gardeners are itching to grow something they can eat and enjoy when there’s not a lot of fresh produce available. Growing microgreens is a great way to bring your love of gardening indoors for the winter and to impress your friends and family with delicious, colorful greens.

- True leaves

- Seed starting area

Microgreens are herb, flower, or vegetable greens grown densely in trays and harvested just after they’ve put on their first true leaves (see photo) when they’re about 1-6 inches tall. These tiny greens are packed with nutrients, color, and flavor, and are easy to grow indoors at home where space is limited. Microgreens can take anywhere from 7 to 28 days to grow, depending on the variety, and they have a predictable growing pattern, making it easy to fit into your busy schedule. Similar to starting seeds indoors, you’ll need to monitor light, temperature, humidity, and water. If you already have a setup for growing seedlings, you can use this same area for growing your microgreens (see photo).

Beginning with the light requirements, there are a variety of greens that will grow just fine on your windowsill without grow lights. Typically these greens are ready to harvest within 10 days, such as peas, pea tendrils, sunflowers, radishes, and buckwheat. For microgreens that take longer than 10 days,, I highly recommend using grow lights. Keep in mind that the quality of the greens will dramatically improve if grow lights are used (see photo 1, photo 2), no matter when they are ready to harvest. Grow lights don’t need to be fancy, they could simply be lamps with light bulbs intended for plant growth (see photo), which can be found at your local hardware store. Since your lights will need to be on for 14 hours during the day, it’s worth purchasing a timer to control when they are turned on and off (see photo – no endorsement intended). Whatever light you use, it doesn’t need to be turned on until after your seeds have germinated. On rare occasions, light isn’t needed at all as is the case with growing popcorn where they’re grown entirely in the dark (see photo).

- Popcorn

- Lamp

- Mild Mix light versus no light

- Peas light versus no light

Similar to starting vegetable seeds, the ideal temperature for growing most microgreens is 65 to 75ºF so be sure to choose an area in your home within this range. I prefer to select varieties based on where I will be growing them in my house. For example, I can grow radish, pea, and brassicas on my windowsill where the temperature is usually 60 to 62ºF, but I don’t grow basil or popcorn in that location.

Maintaining a high humidity when germinating your seeds is very important for consistent and successful germination. High humidity can be achieved by securing a plastic lid or bag, anything that is clean and traps moisture, around your container after sowing your seeds. The plastic lid or bag can be removed after the seeds have germinated (see photo). There is no need to water the microgreens while the seeds are germinating, you will only need to water them right after the seeds are sown and after they’ve germinated. Bottom watering your microgreens is the best way to avoid wetting the young leaves and prevent disease issues. Bottom watering can be done by setting the containers in a tray without holes and filling that tray with water. After 20 to 30 minutes, you can dump excess water from the bottom tray; repeat this process when your microgreen containers have dried out again.

Once your microgreens have reached maturity, it’s ready to harvest them! They can be harvested as they’re consumed or harvested all at once and stored in the refrigerator. To improve shelf life, avoid washing them until right before they are eaten. Some microgreens, such as sunflowers and popcorn, need to be harvested right away to preserve their best flavor, while others, such as basil, should be harvested as they are consumed (see photo).

- Germinated microgreens

- Eating microgreens

Licensing Requirements for Arborists in Maine

Augusta – Following the storms that wreaked havoc on trees across Maine, particularly conifers, it is crucial to engage licensed arborists for trimming limbs and removing fallen or leaning trees. When seeking the services of an arborist—a professional trained in tree care and maintenance—ensuring proper licensure is imperative. To locate a licensed arborist in Maine, refer to the official list on the Arborist List page (Maine.gov).

According to Gary Fish, Maine State Horticulturist, individuals engaging in arborist activities for compensation must be licensed by the state of Maine. Licensing, administered by the Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry (DACF), involves written and oral exams to demonstrate proficiency in tree care and safety. Fish underscores the importance of licensure, stating, “A license indicates that an individual is properly trained, has passed exams, and holds the required insurance.”

Licensed arborists must carry a minimum of $150,000 in general liability insurance for each occurrence and $300,000 in the general aggregate. Fish warns of the inherent dangers of tree work, especially in residential areas, and emphasizes the peace of mind of hiring a fully licensed arborist.

For more information on Maine’s Arborist Licensing Law or to check an individual’s licensing status, visit the DACF website, contact the department at 28 State House Station, Augusta, ME 04333, or email gary.fish@maine.gov.

**Note that the DACF has extended the date for arborist license renewals to January 31, 2024. **

Help Track Forest Pests This Winter

Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry

Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry and our partners concerned about forest health ask that you take some time to familiarize yourself with forest pests at risk of spreading to new areas.

While you are out, look for their signs. If you think you’ve spotted one, snap a picture and record your location. Then let us know at foresthealth@maine.gov or online at www.maine.gov/foresthealth.

Here are two pests that are spreading in Maine. We would really like your help tracking them. Their signs are particularly visible in the winter months.

Emerald Ash Borer

Winter is an ideal time to look for signs of emerald ash borer (YouTube), an insect that kills ash trees (Fraxinus spp.). Hungry woodpeckers go after overwintering larvae of this beetle, removing the bark from ash trees as they do. On ash trees, look for shallow excavation by the birds, bright spots on the trunks where the bark has been removed, and tracks under the bark created by the immature emerald ash borer. Sometimes you can find the larvae, off-white, flattened, legless “grubs” with a tan head and two dark spines at the rear. When there is snow, the contrasting dark bark scattered around attacked trees can be the first clue to emerald ash borer presence.

Emerald ash borer has been found in parts of York, Oxford, Cumberland, Androscoggin, Kennebec, Penobscot, and Aroostook Counties. It was most recently found in Hermon in December 2023. To help people respond to this pest, we would like to know when it is found in new areas (areas outside of the red on the map below).

Learn more about emerald ash borer, caring for ash trees, and regulations and recommendations for use and disposal of ash material on our website.

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

During the winter months, hemlock woolly adelgid must be attached to hemlock trees in order to survive. Therefore, there is very low risk of spreading it this time of year. Also at this time, the insect feeds when conditions are right, and the white waxy tendrils covering its body lengthen. This bright white “wool” makes a sharp contrast to dark hemlock twigs and needles in the low-angled light of winter, making it a terrific time to scout for hemlock woolly adelgid.

Recent high populations and mild winters have allowed this insect to make inroads into new areas of the state. Hemlock woolly adelgid has been found in parts of York, Cumberland, Sagadahoc, Lincoln, Kennebec, Knox, Waldo, and Hancock Counties. When you get outside this winter, help us find it in more locations by looking at the undersides of hemlock twigs, those attached to the tree and those that have recently fallen to the ground, for the tell-tale white balls. December’s epic windstorm brought many branches to the ground, which makes now an opportune time to look for this pest.

Cold winter temperatures limit where hemlock woolly adelgid can thrive. Winter temperatures throughout plant hardiness zones 5a to 6b in Maine (USDA ARS Map below) are expected to be warm enough, frequently enough, to allow detectable populations of this pest to build. This recently updated map shows that many additional areas of Maine are now vulnerable to hemlock woolly adelgid establishment compared to 20 years ago when the pest was first found in Maine.

Healthy forests are essential to Maine’s way of life. When you get outside in Maine, help us keep tabs on the forest. Share our newsletters with friends and coworkers, and get them involved, too.

If you think you’ve spotted a forest pest of concern:

- Snap a picture (you can also gather a sample if is safe to do so),

- Note the location. and

- Reach out! You can use our report form or send us an email.

Backyard Bird of the Month: Golden-crowned Kinglet

By Andy Kapinos, Maine Audubon Field Naturalist

If you’ve got a quarter nearby, hold it in your hand for a moment. That quarter, at approximately 6 grams, is the same weight as Maine’s smallest winter resident bird, the Golden-crowned Kinglet. These tiny, lively birds can survive temperatures as low as -40℉, in part by roosting in small groups, huddled together near the trunk in the protective foliage of a spruce or fir. You are most likely to see Golden-crowned Kinglets in coniferous trees throughout the year; they breed in coniferous forests in the northwestern half of the state and Downeast, especially at higher elevations. In the winter, they are found throughout the state and frequently join mixed foraging flocks with chickadees and nuthatches. Listen for their distinctive, high-pitched calls that sound like two or three notes from a tiny referee’s whistle. You can visually distinguish them by their active foraging behavior, fluttering and hovering around the outer twigs. Even in the winter, Golden-crowned Kinglets eat mostly insects, which they pull from clusters of buds and bark crevices. They are often quite trusting, sometimes foraging close enough for you to see their splendid golden crown. Keep an eye on the conifers in your yard this winter, and you might catch a glimpse of Maine’s smallest winter bird.

Ash Protection Collaboration Across Wabanakik (APCAW)

By Lynne Holland, Horticulture Professional, UMaine Extension, Androscoggin and Sagadahoc Counties

An article each month for the Maine Home Garden News (MHGN) will focus on a topic of interest or concern in what we call Maine and Eastern Canada, but what has been for millennia the Wabanaki homelands. The first topic will be emerald ash borer (EAB).

Maine has new invasive pests to be aware of almost every year, sometimes more than one at a time. Many invasive pests only come to our attention when they become an economic issue. Then, “that new pest” is identified, and specific scientific and governmental groups create resources that identify, quantify, and address the new problem. But with the emerald ash borer, something different happened. EAB was initially flagged in the early 2000s because it threatened a culturally important species (brown ash) and Wabanaki basket-making practices. Basketmakers and Wabanaki researchers called meetings with the state to prepare, which led to the Brown Ash Task Force, a collaboration around ash trees, the EAB problem, and all the people of Maine.

Partners of the Ash Protection Collaboration Across Wabanakik’s (APCAW) was formed in 2022 to continue and bolster previous work done by the Brown Ash Task Force. In addition to networking and research, APCAW provided monthly forums throughout 2023 to inform and educate about the ash tree, its cultural and economic significance, and the threats to its future. According to a radio story from Maine Public, Maine has the distinction of being the last state in the Northeast to discover the presence of emerald ash borers. Like watching a slow-motion train wreck, knowing EAB effects in other states and the vast amount of ash in Maine, this long view of the problem could have been paralyzing.

Instead, the collaboration used the knowledge of the pest’s effects to focus on many facets of ash trees, not just the problem of EAB. One area involves working with local groups around collecting ash seeds and monitoring ash trees that remain after an EAB infestation (known as lingering ash). APCAW is working to address the symptoms, to bolster previous advocacy work to protect brown ash, and to use technology and collaboration to ensure the future of the brown ash tree.

If this brief introduction makes you curious about this collaboration, a good place to start is by listening to the recording of the final webinar (YouTube) of the season. The APCAW site has resources for learning more about the collaboration. There is a newsletter that describes what will be happening in 2024 and opportunities available for you to get involved in. APCAW’s work is to center, protect, and restore the ongoing relationship between Wabanaki peoples and ash trees and welcomes anyone to become involved. In this critical window of time before EAB spreads throughout the region, APCAW is looking for volunteers and willing collaborators, especially landowners, to implement strategies such as seed collection to sustain ash as part of our forest landscape.

A simple way to get started is to walk in the snow. The Maine Forest Service has an online guide about EAB in all seasons, and in winter, EAB is evident by the pile of bark at the base of the tree. If the cultural aspects interest you, then this video is a good place to start: They Carry Us With Them: Richard Silliboy by Jeremy Seifert (emergencemagazine.org).

Book Review: A Northern Gardener’s Guide to Native Plants and Pollinators by Lorraine Johnson and Sheila Colla Illustrated by Ann Sanderson with a foreword by Douglas Tallamy

(Island Press 2023)

By Clara Ross, Master Gardener Volunteer, Penobscot County

This is the third book I’ve reviewed for you regarding native plants and their pollination needs. I’m learning a lot and I hope that you are, too, especially if you take the time to read the books! Each one is somewhat different, but I believe that this one is my favorite.

Doug Tallamy, who in my opinion is a super writer and educator, has written a forward that encapsulates the mission he hopes we will all take more seriously: using native plants to protect and enhance pollinator populations to better ensure the survival of animal life here on Earth. That’s a big one.

Johnson and Colla begin with an introduction: “Pollinators Bring Life.” They present the problem that most folks believe that insects are pests (wasps, beetles, flies, ants, etc.) and must be eradicated. The authors would like us to see insects as part of a hugely intricate community, so suggest that we accept the concept of biodiversity. The authors help us understand the value of many insect critters in helping us grow native plants more successfully.

What I learned (each of these bullets is well expanded upon within the book):

- The various ways plants are pollinated

- Some insects are just out for the nectar and not the pollen

- Most bees do not sting unless they’re bothered

- Nonnative honeybees from infected hives will transfer a virus to plants and then native bees can get the virus, which is one reason for a depleted population of native bees

- Many relationships between insects and flowers are highly specific, for instance, an insect needs a particular pollen to help its larva develop properly

- Varieties of native plants fit into the needs of different pollinators; however, cultivars of natives do not, so when I buy a native, I need to check the fine print

- Natives grown in shady spots like rich, humusy soil, while natives grown in the sun prefer nutrient-poor soil

- For greater success, rather than adapting my soil for a particular native, I should choose a native suited to my soil

- The top native plants to support pollen specialist bees in our area: are goldenrods, sunflowers, asters, coneflowers

- Ways to create a bee hotel

There are many other facts and things to learn, especially about not being fussy about garden cleanup (uh oh), but I’ll stop now and leave you to explore the rest of the interesting goodies offered.

The way that Johnson and Colla’s book is different from the previous two that I reviewed is how these authors organize information for over 300 plants. They begin with spring-blooming natives, then list spring-bloomers that also extend their flowering periods into summer; then summer-bloomers, as well as those that extend their blooming into fall; fall-blooming natives; native grasses and sedges; trees, shrubs, and woody vines. Lots of help for planning a native plant garden.

The book concludes with a variety of tips on using natives to grow a rain garden, developing a bog or pond garden, growing a “boulevard” or strip garden, a list of native plant combinations for particular sites, sample garden designs, as well as other helpful resources.

The gist of the book is that “we do know that native plants and native pollinators function together as part of a huge network of interactions, ‘the architecture’ of biodiversity.” Therefore, human beings have a responsibility to do what they can to help continue this network of life. The authors “provide for you the know-how for (creating and) restoring essential pollinator habitats” (Tallamy). So let’s do it.

The book may be found at your local library; on Amazon in paperback for $27.55; and on Kindle for $30.40.

You can also find a synopsis of the book on Goodreads, Amazon, and Island Press.

Maine Weather and Climate Overview (February 2024)

Dr. Sean Birkel, Assistant Extension Professor, Maine State Climatologist, Climate Change Institute, Cooperative Extension University of Maine. For questions about climate and weather, please contact the Maine Climate Office.

Maine was dealt three impactful storms in close succession – December 18th, January 10th, and January 13th – that had similar tracks producing heavy precipitation and strong southeasterly winds with damaging gusts. Governor Mills has requested a Major Disaster Declaration from the federal government that would avail resources to repair damage across multiple counties from wind and the worst flooding in decades along the Kennebec and Androscoggin rivers. Coastal communities were particularly hard hit in the last two storms, as strong winds coinciding with high tide (including astronomical high tide on the 13th) produced significant to record flooding. Portland, for example, saw a high tide of 14.57 ft as a result of the most recent storm, breaking the previous record of 14.17 ft set in 1978. For more information on resources available refer to the Maine Flood Resources and Assistance Hub on the State of Maine website. These storms developed against the backdrop of a strong El Niño in the Pacific and recorded warm ocean surface temperatures across the North Atlantic. Statewide climate data from NOAA shows that calendar year 2023 was Maine’s 2nd warmest and 5th wettest for records beginning in 1895.

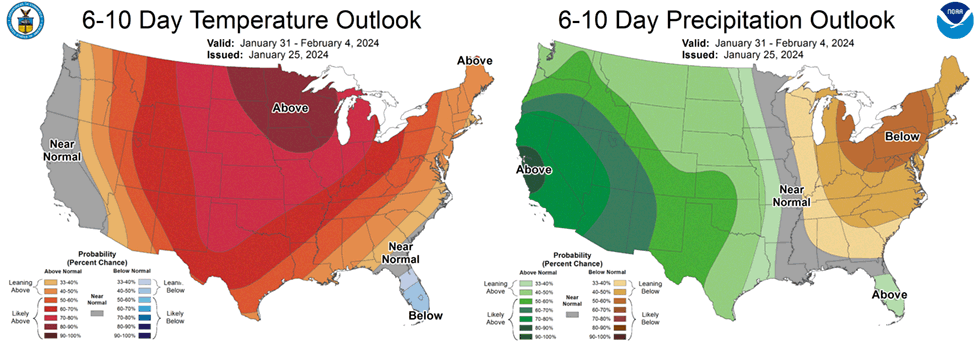

Looking forward, the NOAA Climate Prediction Center 6–10 day outlook probability maps for January 31 – February 4 (issued January 25) show leaning above normal temperature and below normal precipitation for Maine. The 1-month outlook for February (issued January 18) projects above-normal temperature and a lean toward below-normal precipitation. In a recent update, the CPC assessed that conditions across the Pacific are now characteristic of a strong El Niño and that there is a 54% chance the event could become “historically strong” this season. In Maine, El Niño tends to bring warmer-than-normal temperatures, particularly for moderate to strong events such as during the winters of 1997/98, 2009/10, and 2015/16. Maine also saw above-normal precipitation associated with those three events (see for example these El Niño precipitation maps). This is consistent with what we are seeing so far this season.

Be sure to check weather.gov for the latest weather forecasts in your area. For winter weather updates, check out the National Weather Service Gray and Caribou forecast office webpages. For additional climate information, including historical temperature and precipitation data, visit the Maine Climate Office website.

Winter Interest

Our editorial and staff team thought it would be fun to share a few snapshots of features that bring us a little joy in our home landscapes during the chilly winter months.

- These geraniums live in the sunroom until late December or early January when nighttime lows plunge, in the kitchen for the coldest months, back into the sunroom in March, and then outside once spring has really arrived. I’ve had them for years but they just keep on keeping on. – Naomi Jacobs, Penobscot County Master Gardener Volunteer

- The most…unusual source of winter interest in my garden are these willow pinecone galls. When I first discovered them it was in the winter and I couldn’t figure out what kind of shrub had cones but no leaves in winter. But a little research and I discovered these are actually a gall, caused by a small midge. They don’t seem to harm the willow so I leave them! More info here. Rebecca Long, Sustainable Agriculture and Horticulture Professional

- My favorite part of my garden in winter is the view of it in the snow. While I don’t have much landscaping that shows off during the colder months, I do have my big red garden shed as the anchor at the end of my garden space, along with my snow-topped raised beds just waiting for next season. My shed especially is certainly a bright spot and looks so nice with a snowy backdrop. Shelby Hartin, Penobscot County Master Gardener Volunteer

- I planted a fake red-osier dogwood (Swida sericea) shrub in my pocket garden by our front steps using twigs from the office plants we prune every year. While the shrub is too large for year-round placement in that space, this method of inserting twigs into the ground gives the illusion of a shrub during the winter months. Kate Garland, Horticulture Professional

Do you appreciate the work we are doing?

Consider making a contribution to the Maine Master Gardener Development Fund. Your dollars will support and expand Master Gardener Volunteer community outreach across Maine.

Your feedback is important to us!

We appreciate your feedback and ideas for future Maine Home Garden News topics. We look forward to sharing new information and inspiration in future issues.

Subscribe to Maine Home Garden News

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications, click on the Subscribe button below.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

For more information or questions, contact Kate Garland at katherine.garland@maine.edu or 1.800.287.1485 (in Maine).

Visit our Archives to see past issues.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around Maine. The following staff and volunteer team take great care editing content, designing the web and email platforms, maintaining email lists, and getting hard copies mailed to those who don’t have access to the internet: Abby Zelz*, Annika Schmidt*, Barbara Harrity*, Kate Garland, Mary Michaud, Michelle Snowden, Naomi Jacobs*, Phoebe Call*, and Wendy Robertson.

*Master Gardener Volunteers

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2023

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.