Maine Home Garden News, October 2023

In This Issue:

- October Is the Month to . . .

- How to Have Your Own Cranberry Garden

- Ask the Expert Q&A

- Featured Recipe: Turkey Apple Sausage Patties

- Jumping Worms are here in Maine. Here’s what to do if you find them in your garden.

- Maine Weather and Climate Overview (October)

October Is the Month to . . .

By Jonathan Foster, Special Project Assistant, University of Maine Cooperative Extension

Step away from the pruners. While it’s tempting to trim back certain woody plants during fall cleanup, it’s usually best to wait until late winter or early spring to prune most ornamental and edible trees and shrubs. Find more details: Review Bulletin #2169, Pruning Woody Landscape Plants, How Do I Prune Raspberries? (YouTube Video), Blueberry Bush Pruning (YouTube Video), Pruning Apple Trees (YouTube Video).

Step away from the pruners. While it’s tempting to trim back certain woody plants during fall cleanup, it’s usually best to wait until late winter or early spring to prune most ornamental and edible trees and shrubs. Find more details: Review Bulletin #2169, Pruning Woody Landscape Plants, How Do I Prune Raspberries? (YouTube Video), Blueberry Bush Pruning (YouTube Video), Pruning Apple Trees (YouTube Video).

Take in a country fair and revel in the beauty autumn in Maine has to offer. Check out Bulletin #7978, Facts About Leaf Color in Maine before you head out on the road so you can impress your fellow leaf peepers.

Plant garlic and ornamental bulbs after the soil has cooled (typically mid- to late-October). Review Bulletin #2063, Growing Garlic in Maine.

Conversely, dig tender bulbs or bulblike structures after the foliage is hit by the frost (e.g.: dahlias, gladiolas, and canna lilies). For excellent tips on how to cure and store a wide variety of these plants, check out this excellent resource from the University of Minnesota.

Start a compost pile while leaves are abundant. Leaves make an excellent substrate for a compost pile – especially when first shredded with a mower. Collect more leaves in a separate pile to add when depositing food scraps and other high nitrogen inputs.

Leave the rest of your leaves to protect overwintering bees, moths, butterflies, and other forms of life that rely on natural debris for survival. Disease-free leaves also contribute to overall soil and plant health when left in place. Learn more about all of the benefits of leaving the leaves.

Leave the rest of your leaves to protect overwintering bees, moths, butterflies, and other forms of life that rely on natural debris for survival. Disease-free leaves also contribute to overall soil and plant health when left in place. Learn more about all of the benefits of leaving the leaves.

Make some tasty and safe apple cider. For more information, visit the Bulletin #4191, Food Safety Fact: Safe Home-Made Cider.

Score some great deals at a local nursery. It’s not too late to plant trees, shrubs, and perennials. If you don’t have a perfect spot for those terrific half-price impulse purchases, remove them from the pot and temporarily sink them into the ground in a holding area for the winter. Water and mulch well before the ground freezes solid.

Save seed. Be sure to know whether the seeds being saved are going to produce plants with the same traits as the “parent plant” – any plant you may have purchased with “F1” in its name is a hybrid and will not produce the same characteristics. Review Bulletin #2750, An Introduction to Seed Saving for the Home Gardener for more information.

Test your soil. Check out Bulletin #2286, Know Your Soil: Testing Your Soil. Soil testing can be done anytime, but it’s especially helpful to find out what needs to be added to the soil and incorporate it when there are typically fewer other garden chores to be done.

Stretch the growing season a few more weeks, or even longer, by constructing a simple low tunnel over cold-tolerant crops such as spinach and kale. If using plastic to cover the low tunnel, vent on warm sunny days to prevent overheating. See Bulletin #2752, Extending the Gardening Season.

Dry those beautiful herbs. Visit Bulletin #4275, Let’s Preserve: Dried Herbs or make your own herbal vinegar. Don’t miss the opportunity to gather mint, oregano, thyme, and other items that will be much appreciated in teas and soups this winter.

Find the best place to store fresh produce to ensure a longer shelf life. Not all produce should be treated the same. Review Bulletin #4135, Storage Conditions: Fruits and Vegetables.

How to Have Your Own Cranberry Garden

By Charles Armstrong, Cranberry Professional, University of Maine Cooperative Extension

Cranberry lovers will be happy to know that it’s possible to grow their own crop with a little research and site preparation. Contrary to popular belief, cranberries do not grow in water. While the bulk of the advertising for cranberry products shows nothing but cranberries floating in seemingly endless oceans of water, after about two weeks of being completely saturated the roots begin to run out of oxygen. While it is true that cranberries are a wetlands plant and are better than most species at tolerating flooded conditions, they thrive in moist, well-aerated, acidic (pH of 4.0 to 5.5) growing medium such as sand or peat, or a combination thereof – making it a very doable crop for many Maine landscapes.

Cranberry lovers will be happy to know that it’s possible to grow their own crop with a little research and site preparation. Contrary to popular belief, cranberries do not grow in water. While the bulk of the advertising for cranberry products shows nothing but cranberries floating in seemingly endless oceans of water, after about two weeks of being completely saturated the roots begin to run out of oxygen. While it is true that cranberries are a wetlands plant and are better than most species at tolerating flooded conditions, they thrive in moist, well-aerated, acidic (pH of 4.0 to 5.5) growing medium such as sand or peat, or a combination thereof – making it a very doable crop for many Maine landscapes.

About the Plant

Cranberries are in the genus Vaccinium, which—together with the likes of blueberries, lingonberries, and huckleberries—belong to the Ericaceae or heather family. They are sun-loving (the more sun the better), produce flowers and fruit year after year, and are adapted for nutrient-poor acid soils. Their roots, most of which are quite shallow, are associated with mycorrhizal fungi that are essential to the survival of the plants, greatly increasing the ability of the roots to absorb nutrients and water.

The plants themselves are characterized by two different types of growth habits: runners, which are vines that trail along the ground (not unlike a strawberry plant), and uprights, which arise upwards from nodes along the runners. It is the uprights that bear the flowers and hence, the berries. A typical ‘fruiting’ upright stores enough nutrients and sugars to be able to support an average of just two cranberries, but occasionally will produce up to five. Roughly half of all uprights will be non-flowering, or vegetative only. The vegetative uprights will generally become ‘flowering’ (i.e. fruiting) uprights the following year and then will cycle back to vegetative again the year after, and that pattern will keep repeating itself.

Preparing the Bed

Select a full-sun site that is appropriately sized to your production goals. A 4’x8’ area would be considered a large plot. In general, every 5 sq. ft. of bed is expected to yield a pound of cranberries yearly if the plants are healthy and at least 3 years old.

Select a full-sun site that is appropriately sized to your production goals. A 4’x8’ area would be considered a large plot. In general, every 5 sq. ft. of bed is expected to yield a pound of cranberries yearly if the plants are healthy and at least 3 years old. - Grab a shovel and start digging (the hardest part of the process). A depth of 8” to 12” is recommended. A few cranberry roots will eventually venture down to 12” while the vast majority will remain just 4 to 6” below the surface. Use what you dig out of the area to form a protective wall or berm around your bed to help slow the encroachment of weeds and to maintain good separation between the bed and your lawn. You can also cover the berm with wood and/or plastic, which works very well at keeping out the weeds.

- Fill your entire plot with peat moss, or a mixture of peat moss and sand (but save out some of your sand for later use). Add in some slow-release fertilizer if you desire (spring or early summer only). Also, it doesn’t hurt to add a little potting mix and/or compost, especially closer to the surface, to help give some additional body and nutrients to the mixture. Moisten it all gradually and mix it frequently to expose any dry pockets. Once you are finished mixing and wetting, it helps to add 1-2” of sand to the uppermost layer. The sand will help to anchor the plants and aid in weed prevention. Adding an additional half inch to 1” of sand every two to three years after planting will yield additional benefits, helping with not only weed control but insect and disease control as well. This periodical sanding also encourages greater upright formation from the runners, having essentially a pruning effect on the vines.

- Except during the first season after they are planted, during extended dry periods, or on extremely hot days, you needn’t worry too much about watering the bed. Peat moss holds moisture extremely well. As long as it is moist 1” below the surface, that’s fine. It’s also good to give plants some extra water when berries are present to ensure the fruits remain nice and plump. The ‘fruit’ of the cranberry is 87% water!

- Keep the area weed-free. This is a key part of early establishment as well as long-term maintenance. While the top layer of sand can reduce weed pressure, there will still be potential for weed competition.

Acquiring Plants and Planting the Bed

Where do I find plants?

Searching online using keywords such as “purchase cranberry plants” will yield some good choices for plants, including a Maine grower-owned option, where you can also find some additional planting and care instructions for your new bed. Another alternative that some folks have attempted, with varying success, is to transplant existing cranberry plants found in the wild if you know them to be good producers. Planting from seed is generally not a good idea simply because most seeds fail to germinate. Also, since any of the resulting offspring are not genetically identical to the parent, usually you are left with mostly vegetative, non-fruiting genotypes. In other words, with seeds, you can never be sure what you’re going to get.

Searching online using keywords such as “purchase cranberry plants” will yield some good choices for plants, including a Maine grower-owned option, where you can also find some additional planting and care instructions for your new bed. Another alternative that some folks have attempted, with varying success, is to transplant existing cranberry plants found in the wild if you know them to be good producers. Planting from seed is generally not a good idea simply because most seeds fail to germinate. Also, since any of the resulting offspring are not genetically identical to the parent, usually you are left with mostly vegetative, non-fruiting genotypes. In other words, with seeds, you can never be sure what you’re going to get.

How many plants?

It’s a good idea to begin with a minimum of four to six mature potted plants (ideally 6” diameter pots) for a 4’ x 8’ area with each plant having about a 2’ x 2’ spacing. Plants can be spaced more tightly if you wish to have them form a mat more quickly, which can be beneficial for crowding out weeds. More widely-spaced plants is also a fine approach but may require more frequent weeding initially. Starting with older plants (at least 3 years old) is also a sensible strategy, as you won’t have to wait three to four years before seeing any significant fruit because the root system will be more developed and ready to support lots of berries.

When to plant?

Cranberries in Maine can be planted as late as the first part of November, but the best time is in the spring during the month of April. This will give the plants an entire growing season in which to establish themselves and to adapt to their surroundings. It will also ensure that they are ready for winter, having had the full time to respond to the shortening daylight cues and to more fully develop their root systems.

Winter Protection and Frost Control

Mulch your cranberry plants every year shortly before the ground freezes around late November. You can use peat moss, pine needles, leaves, or any combination thereof. Pine needles are especially acidic, so they help your bed maintain the low pH that the cranberries like, but sometimes hardwood leaves provide a better covering on the very top as they don’t simply fall through the empty spaces as much. If it is a particularly snowy winter, snow by itself will insulate the plants. However, as our recent winters have demonstrated, one cannot always depend on having a pile of snow over the bed for the entire winter. The barrier that the snow and mulch create is not for the purpose of insulating against low temperatures nearly as much as it is meant to insulate the plants from the desiccating nature of the wind. Since cranberry leaves are evergreen, they are subject to drying out in the presence of winter winds. Growers refer to cranberry tips and leaves damaged this way as having died due to ‘winter kill.’ Often the plants will recover, but not if the injury is too severe.

Uncover the plants in early April, but be on guard against dangers from frost. Cover them up again if you suspect a dangerous frost event, especially if the buds have begun to swell and change color from their dormant red to a shade of green.

New shoots that are starting to elongate from the buds in the spring need to be protected from frost. The tolerance levels vary somewhat depending on what variety you have and the stage of growth. For the variety ‘Stevens’, new shoots in the spring can withstand temperatures as low as 29.5 – 30 F (as low as 20 F if the buds are still dormant and not growing). In the fall, by the end of October, ‘Stevens’ vines will tolerate temperatures down to 23 F. Perhaps just apply your winter protection a little early if there is a real danger of frost at that time. You can find a table of both spring and fall frost tolerances for different varieties and growth stages on the Frost Tolerances page.

Additional Information

Please take a peek at UMaine Extension’s cranberry website for information on additional topics such as pest ID, fertilizer questions and recommendations, grower services, cranberry health benefits, cranberry educational activities for kids, and more. How to Plant Cranberries (YouTube Video)

Ask the Expert

Q: Do ultrasonic deer repellents work? We have a string of arborvitaes which the deer love to munch on in the wintertime. Is fencing the only other alternative? We have tried sprays and clip on deterrents but nothing like that works.

A: The short answer, in my experience, is that none of the products marketed for this purpose, or the truly ingenious ideas gardeners and homeowners have come up with over the years to deal with browsing deer, are effective in the long term. Deer are voracious, persistent mammals who eventually adapt to just about everything other than physical separation from the plant you want to protect. There is evidence to suggest that some deterrents can mitigate the feeding damage, but they wash off easily and must be reapplied frequently and thoroughly; even then, they won’t be 100% effective. The other thing you can do, moving forward, is to select deer resistant plants so as not to attract them to your yard. Obviously, that won’t help with your arborvitae, but it’s good to keep in mind that you have deer when purchasing other plants or doing landscaping. Fencing (including possibly electric) is the only sure fire way to keep the deer out of your yard and garden.

Answer provided by Jonathan Foster, Special Projects Assistant

Read more in this great resource from the UNH Extension.

More great questions and answers can be found on our Ask the Experts website.

Featured Recipe: Turkey Apple Sausage Patties

By Kayla Parsons, Ph.D. student, RDN, University of Maine Cooperative Extension; Reprinted from University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Food and Nutrition blog.

There’s nothing better than a breakfast that hits multiple flavor profiles. This Mainely Dish Turkey Apple Sausage recipe is sweet and savory, encapsulating the feeling of fall when you taste the combination of apples, nutmeg and fresh sage. This easy-to-follow recipe is a great way to add in additional protein to your usual breakfast. My favorite way to use this recipe is to crumble the cooked sausages into a frying pan with scrambled eggs and spinach, and eat on a slice of whole wheat toast with whatever fruit I have in my fridge on the side. There’s also something nice about finding a new apple recipe in the fall, because let’s be honest, we all probably picked way too many apples last weekend at our local apple orchard.

Don’t have a designated apple peeler at home? All you need is a paring knife. After washing your hands and the apples, hold the paring knife in your dominant hand. Beginning at the stem of the apple, press the knife away from you and against the apple skin. Rotate the apple with your opposite hand, and the skin will then peel off like a ribbon. This skill takes practice and there’s no harm if some peel is still on the apple prior to shredding.

Turkey Apple Sausage Patties (YouTube)

Resources:

Jumping Worms are Here in Maine:

Here’s what to do if you find them in your garden.

By Lynne Holland, University of Maine Cooperative Extension Horticulture Professional and Shelby Hartin, Master Gardener Volunteer in Penobscot County

What are jumping worms?

Jumping worms, or Amynthas worms, “are a type of earthworm native to East Asia,” according to the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry. “They are smaller than nightcrawlers, reproduce rapidly, are much more active, and have a more voracious appetite. This rapid life cycle and ability to reproduce asexually gives them a competitive edge over native organisms, and even over nightcrawlers. When disturbed, Amynthas worms jump and thrash about, behaving like a threatened snake.”

What do they look like?

The UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery and Urban Forestry Program has an excellent fact sheet that’s helpful to reference. Jumping worms are “smooth, glossy, and dark gray/brown in color. A mature adult is 4-5 inches long. (However some sources note that these species can be 1.5 – 8 inches in length during their lifetime.) Their clitellum (a lighter colored band around the worm) is cloudy-white to gray in color and completely wraps around the body of the worm. The surface of the clitellum is also flush with the body. The clitellum is found relatively close to the head of the worm, approximately 1/3 the total length of the worm from the head. Adult worms are firm and not coated with a slimy substance. They will thrash violently when disturbed, and are often found in large groups of individuals. Jumping worms do not burrow deep into the soil and are typically found on the soil surface in debris or leaf litter,” according to the fact sheet.

Why are they such a concern?

These worms have the potential to cause long-term damage in our forests. The Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry reports that “they turn good soil into grainy, dry worm castings (aka poop) that cannot support the native understory plants of our forests. Other native plants, fungi, invertebrates, and vertebrates may decline because the forest and its soils can no longer support them. As native species decline, invasive plants may take their place and further exacerbate the loss of species diversity.”

What do I do if I think I’ve found them in my garden?

First, don’t panic. Second, ensure that you positively identify the worms (see “what do they look like?” above). You can also reach out to your local Extension office if you would like help with identification. Once you’ve positively identified the worms, you can remove and destroy them by dropping them in a bucket of soapy water or sealing them in a plastic bag. Don’t use pesticides, chemicals, home remedies or other products – there are currently no approved methods to manage these worms and some recommendations found online can have serious negative consequences to non-target organisms.

Next, and perhaps most important, make sure you report your findings to the state. You can do so here (at the bottom of the page is a section labeled “What Can You Do.” Please read that section as it has instructions and links for reporting this issue).

How did they get in my garden in the first place and how can I avoid spreading them elsewhere?

That is not an easy question to answer. They may have been unwelcome hitchhikers in soil, compost, or plants you have added to your garden in the last couple years. If you haven’t brought in plants or soil amendments, they likely came in from the dirt on a tire, shoe or something someone dumped in that area.

The best thing you can do is make sure you don’t share any plants/soil from your site and clean the bottom of your shoes after walking in areas where there’s a known infestation. Jumping worm eggs overwinter in the soil so they are easy to spread – even by walking.

Where can I find more information?

The Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry recently provided an update on jumping worm research as part of their “Forestry Friday” series. The Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry also recommends the Jumping Worms guide (PDF) from Oregon State on its website.

Maine Weather and Climate Overview (October)

By Sean Birkel, Assistant Extension Professor, Maine State Climatologist, Climate Change Institute, Cooperative Extension University of Maine. For questions about climate and weather, please contact the Maine Climate Office.

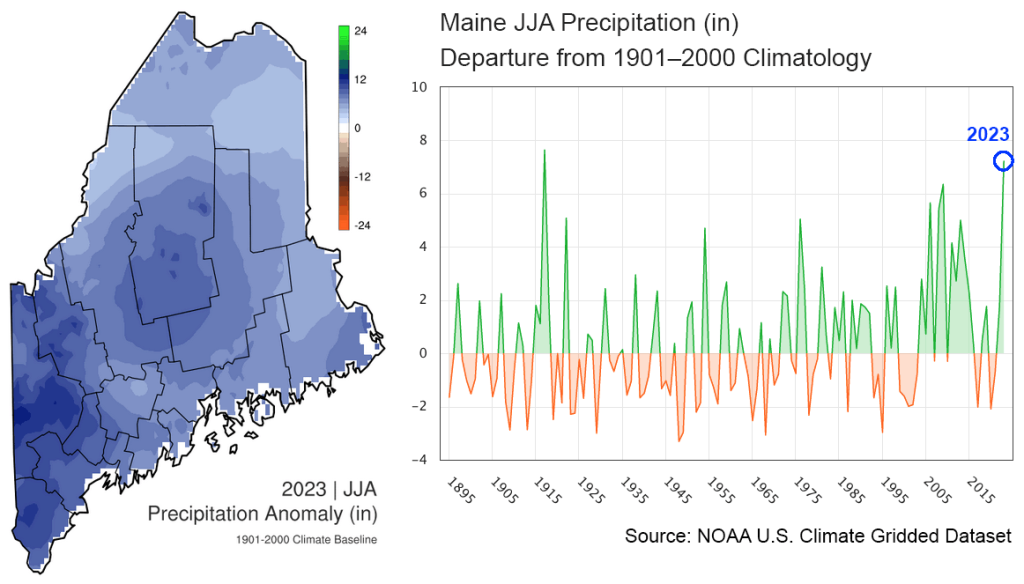

NOAA data released in mid September shows that the 2023 summer (JJA) was the 2nd wettest in Maine on average statewide for records beginning 1895 (see data on the Maine Climate Office website). The 1st wettest JJA period was 1917, and the 3rd was more recent in 2009. This year’s wet growing season stands in sharp contrast to recent summers in which Maine experienced varying levels of drought. The average JJA temperature was warmer than usual in the 87th percentile. A particular standout record is from July, where persistent humidity contributed to the warmest monthly minimum temperature, 60.6°F, besting July 2010 by 1.7°F.

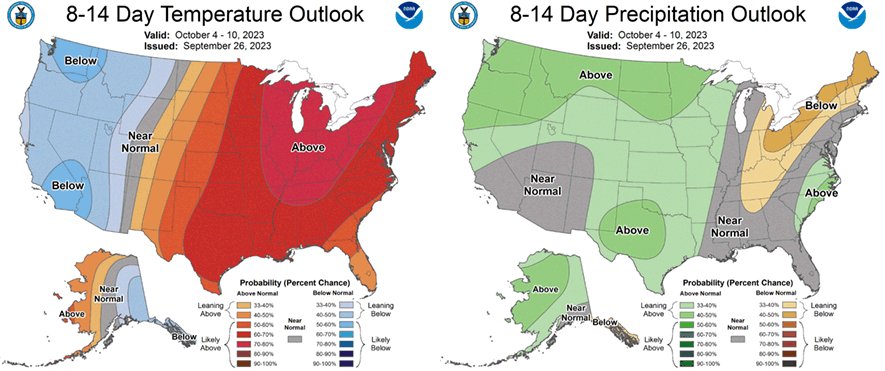

The first two-thirds of September continued the overall pattern of warmer, wetter-than-normal conditions. However, since shortly after Tropical Storm Lee impacted Maine mid-month, large-scale weather patterns have brought generally seasonable temperatures, sunshine, and dryness. As of September 27th, the National Weather Service forecasts a chance of rainfall early in the first week of October. Beyond that the NOAA Climate Prediction Center 8–14 day outlook probability maps for October 4–10 (issued September 26) show likely above normal temperature and leaning below normal precipitation for Maine. The 1-month outlook for October (issued September 21) similarly shows above normal temperature and below normal precipitation. These and other maps are available on the Maine Climate Office website. And as always, be sure to check weather.gov for the latest weather forecast for your area.

Do you appreciate the work we are doing?

Consider making a contribution to the Maine Master Gardener Development Fund. Your dollars will support and expand Master Gardener Volunteer community outreach across Maine.

Your feedback is important to us!

We appreciate your feedback and ideas for future Maine Home Garden News topics. We look forward to sharing new information and inspiration in future issues.

Subscribe to Maine Home Garden News

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications, click on the Subscribe button below.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

For more information or questions, contact Kate Garland at katherine.garland@maine.edu or 1.800.287.1485 (in Maine).

Visit our Archives to see past issues.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around Maine. The following staff and volunteer team take great care editing content, designing the web and email platforms, maintaining email lists, and getting hard copies mailed to those who don’t have access to the internet: Abby Zelz*, Annika Schmidt*, Barbara Harrity*, Kate Garland, Mary Michaud, Michelle Snowden, Naomi Jacobs*, Phoebe Call*, and Wendy Roberston.

*Master Gardener Volunteers

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2023

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.