Climate Highlights: Climate Change and Agriculture in Maine

By Laura Poppick

A Northward Shifting Climate

Plants are sensitive to temperature and moisture conditions in the atmosphere. Different plant types prefer different atmospheric conditions, which is why the arctic tundra hosts a different suite of plants than the deciduous forests of New England, which, in turn, host different plants than the Florida Everglades. Descending through Earth’s latitudes, shifts in temperature and moisture conditions sculpt varied strips of plant communities.

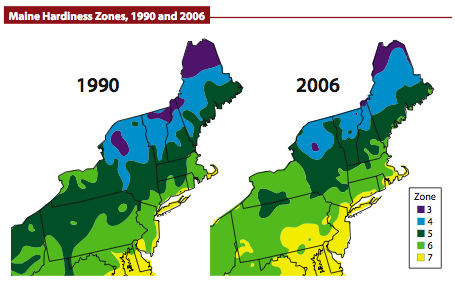

The borders of climatic zones blur and are susceptible to change. As Maine farmers begin to consider this reality, they are already facing the consequences of global climate change. Waves of warmer temperatures have promoted longer growing seasons and migration of new weeds and pests that previously could not withstand Maine’s cool climate. The Arbor Day Foundation has officially documented a northward shift in minimum winter temperature in Maine from 1990 to 2006, revising its Plant Hardiness Zone Map of Maine and suggesting a northward shift in the plant communities that thrive here.

How will these shifts change agriculture in Maine? Relative to other regions of the country, Maine is potentially in a position of strength. If managed properly, the resulting biome shifts and longer growing seasons will increase crop yield and may allow previously unviable crop types and management techniques to become viable, ultimately strengthening Maine agriculture. Meanwhile, increased climate change and sustainability awareness amongst Maine citizens has already benefited the local food economy. As we continue to invest more in locally produced food, we are collectively building a support system that will allow Maine farmers and local economies to weather the change.

The Wild Blueberry Story

The wild blueberry industry in Maine has seen dramatic growth, nearly tripling in crop yield over the past 10 years. David Yarborough, the blueberry specialist at the University of Maine Cooperative Extension, explains that this has largely resulted from improved management techniques, but is also the product of lengthened growing seasons associated with climate change. “Longer falls and earlier springs allow plants to store more nutrients in buds, store more buds, and ultimately produce a larger crop,” Yarborough explained.

But changes in seasonality are not unilaterally positive, Yarborough pointed out. “On the other hand, when spring occurs three weeks early, unexpected frosts hit fields away from the coast, and a 70 million pound crop decreases to 15 million pounds,” he said.

Climate-related challenges also are unearthing later in the growing season, when abnormally high midsummer temperatures threaten the berries during their peak growth period. “When the temperature shifts from 78°F one day to 95°F the next day, a 40-acre blueberry farmer can watch his whole crop boil, and there is really nothing he is going to be able to do to change that,” said John Jemison, water and soil quality specialist with Cooperative Extension.

Still, despite these see-sawing climatic obstacles, crop yields are higher than ever. Yarborough attributes much of this success to increased bee importation for pollination, which has substantially improved crop fertility. Maine is now the second largest user of bees for pollination in the country, importing 50,000 to 60,000 hives each year. Increased media coverage of the health benefits of wild blueberries as antioxidants has also increased wild blueberry demand and has thus supported a stronger market.

While proactively increasing crop fertility and desirability has allowed the blueberry market to thrive this past decade, future success in the face of climatic instability requires more defensive measures. Farmers must prepare for unexpected droughts and flood-induced soil loss through updated water and land management protocol. New pests and diseases carried by warmer airwaves will call for innovations of Cooperative Extension’s Integrated Crop and Pest Management systems. And, as latitudes north of Maine begin to thaw, increased competition with burgeoning Canadian markets will require Maine farmers to be ever more scrupulous with their practices. Already, improved management and warmer temperatures have allowed the New Brunswick annual crop yield to increase from 5 million to 70 million pounds within the last ten years, creeping close behind Maine’s leading yield of 80 million pounds.

Can Management Save Maine Agriculture?

Yarborough and Jemison both optimistically believe that mindful management practices can push Maine agriculturalists through the hoops of climate change. And, while posing obvious obstacles, climate change may also actually validate previously unviable management practices. For example, Yarborough knows that springtime blueberry-field burning is an effective pest and disease management technique, but farmers currently hesitate to adopt this method because it shortens their growing season. As fall occurs later and lasts longer, however, springtime burning will pose less of a threat to net crop yield.

Maine’s temperate climate and relatively consistent season-to-season precipitation rates also offer a baseline level of security that other regions of the country do not have. And while droughts in the past have certainly dried up some blueberry fields, Yarborough said this has everything to do with water distribution, not quantity.

In a paper recently published in the Journal of Environmental Management, University of Maine environmental engineers Avirup Sen Gupta, Shaleen Jain, and Jong-Suk Kim addressed water distribution in Maine in response to climate change. They suggested increasing the scientific basis of the Maine Department of Environmental Protection’s emerging water allocation framework by integrating more paleoclimate data into future risk assessments. Accordingly, they present a new map of relative hydrologic risks throughout Maine contingent with the number and nature of droughts that have occurred over the past millennium.

Such research-based advancements in agricultural management are aplenty in Maine, with close interactions among academic researchers, extension specialists, and farmers. Jemison, who studies nutrient and weed management and promotes double-cropping for soil erosion management, tells farmers, “We need to be more aggressively protecting our resources. If you’ve got your fields covered, and are actively working to protect your resources, then you’ll be in a position of strength regardless of what comes.”

Climate Change Awareness and the Local Food Movement: A Prosperous Future

In May, the Bangor Daily News reported a $4,000 increase in sales this year at the Machias Marketplace, a local buying club, demonstrating marked growth in the local food movement in Washington County (Local food movement growing in Washington County, May 24, 2011, Bangor Daily News). Elsewhere in the state, grocery stores are increasingly stocking locally grown products. Rising Tide Community Market in Damariscotta, Rosemont Market & Bakery in Portland, and Hannaford in Augusta are three of 10 grocers recently recognized by the Maine DEP for voluntarily selling local food products (Maine DEP Certifies Environmental Leader Grocers, May 23, 2011, Maine Department of Environmental Protection website). When I asked a worker at Rosemont Market & Bakery on Congress Street if he thought climate change and sustainability awareness has benefited the local food economy, he answered, without hesitation, “Oh, absolutely.”

Buying food from neighbors decreases the carbon dioxide emissions associated with transcontinental food importation and enjoying tastier and more nutritious foods strengthens Maine communities.

While certainly not trivial, impending changes in climate need not cast a shadow of doom over Maine – change has already illuminated a growing sense of community resourcefulness that is laying the foundation for a prosperous future.

References and Resources

The Arbor Day Foundation. 2006. Differences between 1990 USDA hardiness zones and 2006 arborday.org hardiness zones reflect warmer climate.

Cooperative Extension: Maine’s Native Berry. 2011.

Griffin, T. 2009. “Agriculture”. In Jacobson, G.L., I.J. Fernandez, P.A. Mayewski, and C.V. Schmitt (editors). 2009. Maine’s Climate Future: An Initial Assessment (PDF). Orono, ME: University of Maine. pp. 39-42.

Sen Gupta, A., Jain, S., and Kim, J-S. 2011. Past climate, future perspective: An exploratory analysis using climate proxies and drought risk assessment to inform water resources management and policy in Maine, USA. Journal of Environmental Management 92: 941 – 947.