June-November, 2015

Weather and Climate Review: June-November 2015

By Sean D. Birkel, Maine State Climatologist, December 6, 2015

This note covers events of June-November, summer and fall. Bear in mind that nature is fluid, and seasons in Maine do not always line up nicely with our rigid constructs. That means I may give a eulogy for, say, winter, in early March, when in fact winter may linger into April. But we shall cope.

In Review

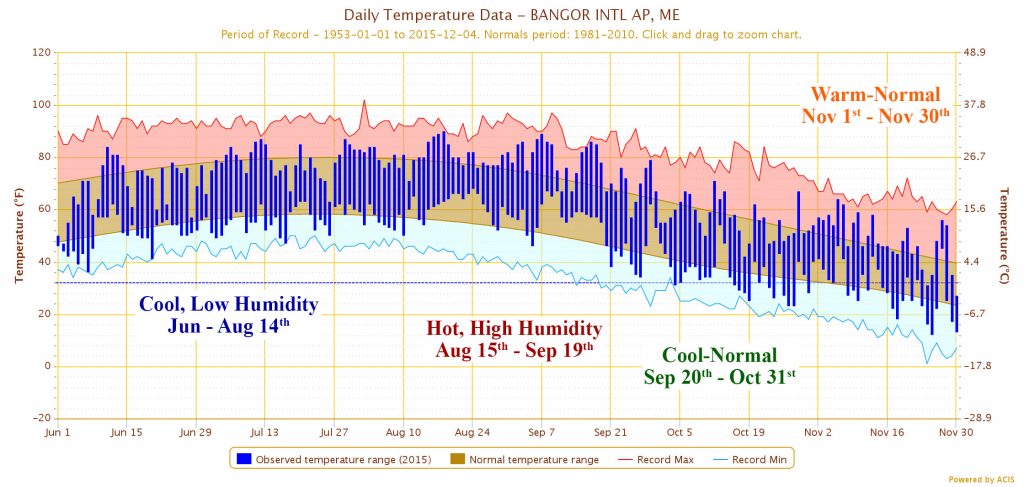

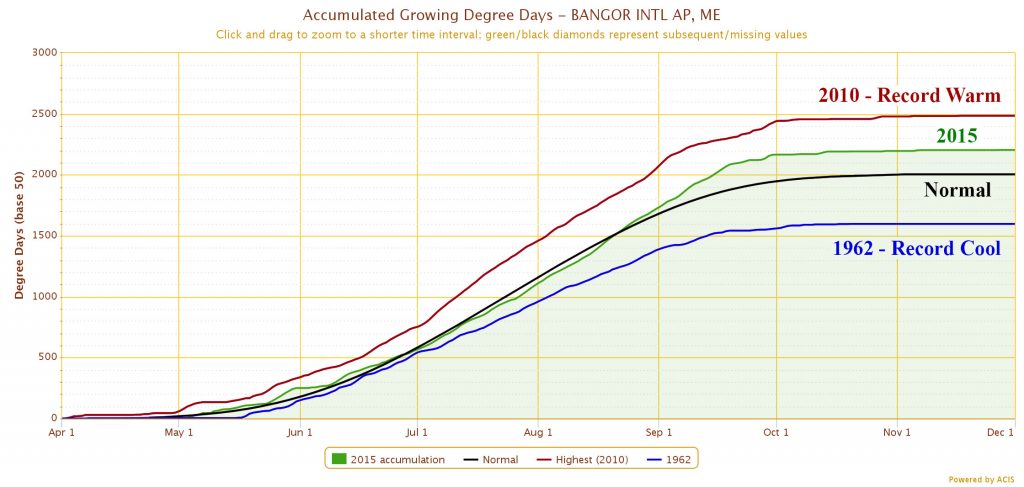

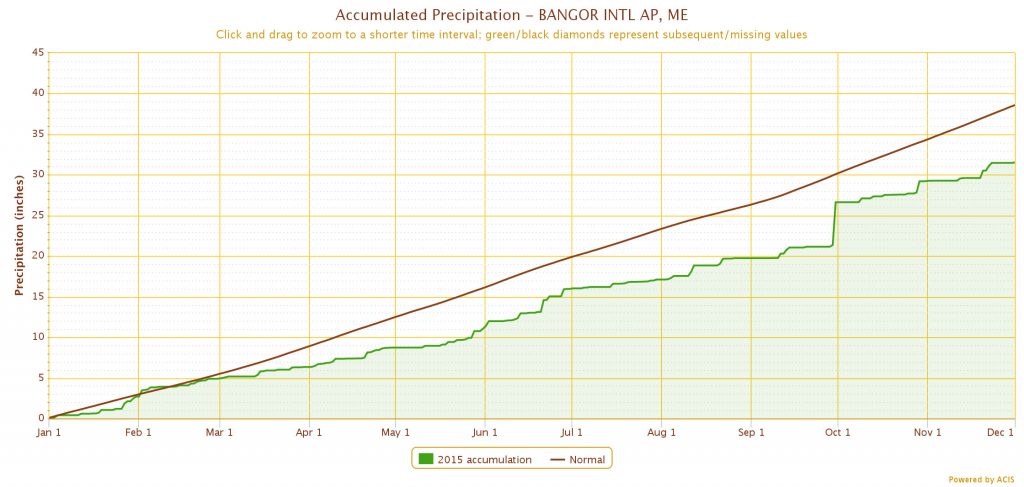

A picture, or graph as it may be, is worth a thousand words, and Figure 1 likewise tells us a lot about the general temperature pattern in Maine since June 1. Many will recall that from about the first of June (or even mid-May) through mid-August temperatures were mild and humidity was low. The tally of growing degree-days ran below normal (Figure 2). Atmospheric circulation during this period brought frequent northwest winds off Hudson’s Bay. Then, just as it looked as though the entire summer would be cooler than normal, a moderate heat wave set in around August 15 and persisted until about the third week in September. Hot, humid, and hazy. This unusually warm weather pattern, in addition to below-normal accumulated precipitation for the year (Figure 3), brought unseasonably late onset of fall color across the entire state. But with the arrival of cool overnight temperatures in early October, a surprisingly vibrant foliage display emerged. October was cooler than normal overall; November started warmer than normal and ended near normal.

El Niño

The big climate story this year has been the development of a particularly strong El Niño, an event that continues to impact global weather patterns. El Niño is the warm phase of the El Niño-La Niña Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a mode of ocean-atmosphere climate variability with characteristic changes in sea surface temperatures across the equatorial Pacific every 3-5 years (What are El Niño and La Niña? page, National Ocean Service website). Figure 4 illustrates global sea-surface temperature anomalies as of November 30; the broad swath of warm surface waters across the equatorial Pacific really stands out.

Impacts from El Niño so far this year have included a record active Pacific typhoon season and an overall weak Atlantic hurricane season. Pacific storms have been fueled by warm surface waters and greater atmospheric moisture content, whereas Atlantic storms have generally fizzled from upper-level wind shear that tends to occur downstream of the Pacific during El Niño (view the NOAA explanation of the impact of wind shear on hurricane development on the Behind the 2015 Atlantic Hurricane Season: Wind Shear & Tropical Cyclones page, Atlantic Oceanographic & Meteorological Laboratory website).

El Niño 2015 is ongoing and may exceed the intensity of the record 1997-98 event. Conditions thus far follow two years of warm circulation across the North Pacific that has been tied to strong jetstream ridging over western North America, and the related Californian drought. Visit the Climate Update: Maine’s 2014-2015 Winter Season page to view my previous article discussing how the unexpected cold winters of 2013-14 and 2014-15 arose in part from a trough pattern that developed over eastern Canada downstream of the western ridge.

What does El Niño mean for Maine, and what might this winter bring?

El Niño and its cool-circulation counterpart, La Niña, affect eastern North America through the propagation of upper-level waves in the atmosphere, i.e., the jet stream. Because Maine’s weather is influenced by a number of atmospheric teleconnections, the impact of Pacific phenomena can be trumped by wave patterns developing elsewhere, particularly across the North Atlantic. The impact of El Niño on Maine, therefore, is not well defined.

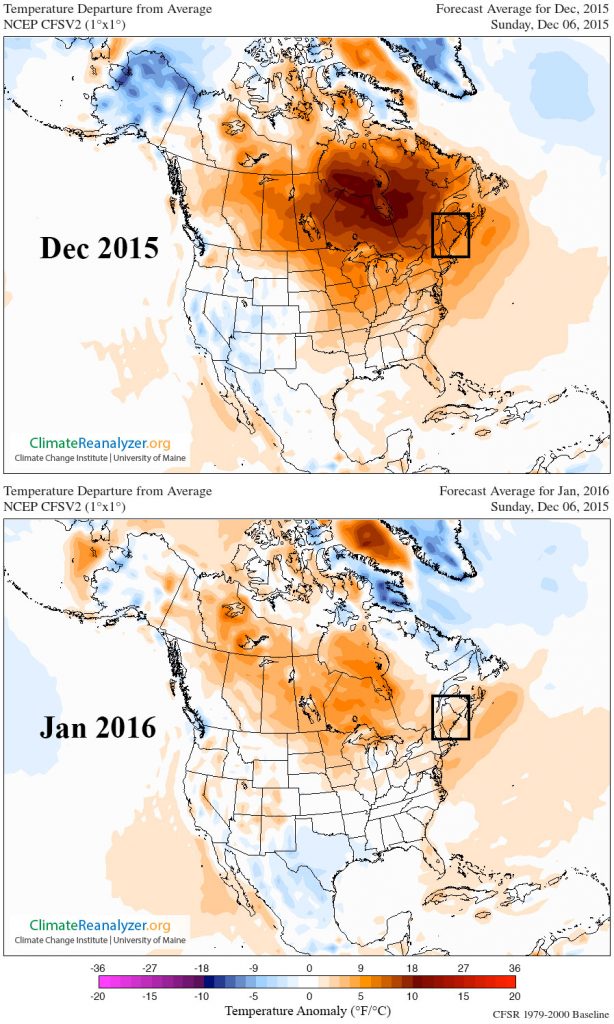

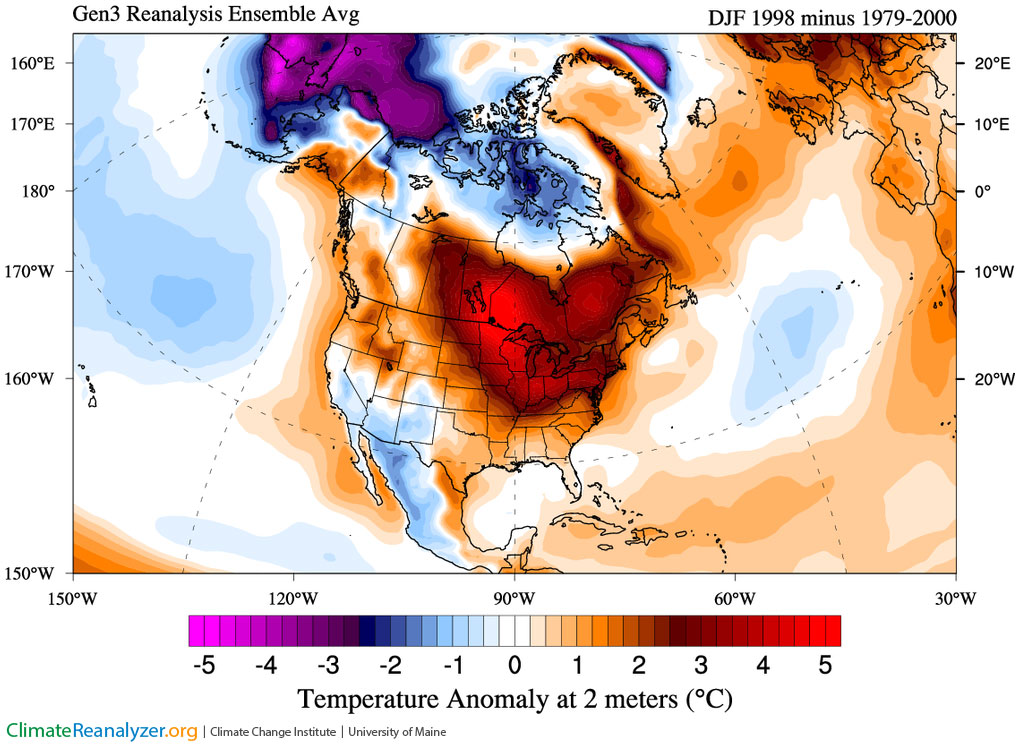

Although Pacific climate variability may not have a clear signature impact on Maine, it is worth noting that the well-remembered Ice Storm of January 1998 occurred during the record El Niño event of that year. The current ensemble-average forecast outlook from NCEP/NOAA for North America shows above-normal warmth for both December and January for most of Canada and the central to the eastern U.S. (Figure 5). The forecasted temperature pattern is comparable to that of winter 1998 (Figure 6). Perhaps this is an El Niño signal.

A warm winter in Maine is one in which storms track farther inland than normal, owing to a more northward position of the jet stream. That means a greater likelihood of temperatures above freezing, along with snowfall events ending in rain or mixed precipitation. We will probably not see a repeat of the intense cold and plentiful powder-like snowfall of last winter.