May-July, 2015

Climate Update: May-July, 2015

By Sean D. Birkel, Maine State Climatologist, August 2015

My previous update, Winter 2014-2015, covered the Maine winter of 2014-2015, a season that included some rather exceptional events. The first event was an early November winter storm that caused widespread tree damage and power outages. This storm ushered in a weather pattern that brought colder-than-normal temperatures for the remainder of the month. Many lakes froze early. But everything changed in December when a month-long warm wave effectively erased all of winter’s early gains. December turned out to be the sixth warmest statewide since 1895. Winter returned with a vengeance in January with normal to below-normal cold, and record or near-record snowfall in many areas across the state. Then came February. February was cold, the coldest month on record in the state. That’s impressive, for one, because January is on average the coldest month of the year. March was also colder than normal, but not a record breaker. Spring finally came around the first week in April, but spring cheer was dashed briefly by snowfall in some parts of the state on April 12.

In contrast to last winter, the months since have seen overall normal conditions across Maine. No single event stands out as being particularly noteworthy. But climate extremes are in fact everywhere around us, driven in large part by the emergence of what could be a very strong El Niño. El Niño is the warm phase of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) (PDF), a quasi-cyclical (3-5 years) change in sea surface temperature across the equatorial Pacific. The cold phase of ENSO is known as La Niña. El Niño, in particular, has a reputation for triggering wild weather due to the addition of heat and moisture into the tropical atmosphere, which in turn affects changes in large-scale circulation. This current warm phase of ENSO began in late 2014, and the dominant circulation feature that has emerged is strong ridging in the jet stream over the western half of North America. Downstream of the ridge there has been a persistent trough bringing cold airflow from Canada into New England. Hence, Maine experienced a cold winter and a relatively cool summer. Meanwhile, in conjunction with the unabated rise in greenhouse gases, steady warming across the eastern Pacific in this strong ENSO cycle has lead to anomalously high global temperatures. Both NOAA and NASA report that July (and the January-July average) 2015 was the warmest on record (Global Climate Report – July 2015 page, NOAA website).

Figure 1. U.S. temperature and precipitation anomalies (departure from long-term mean) for May-July of this year. The three-month averages for both metrics are near normal for Maine (outlined), but there are significant departures elsewhere. For example, in the Southeast (hotter and drier than usual), the Rockies and central plains (cooler and wetter), and Pacific Northwest (hotter and drier). A key factor underlying these extremes is the warming surface waters of the eastern Pacific Ocean associated with the development of El Niño. Click on image to enlarge. Data source: NCEP CFSV2/CFSR.

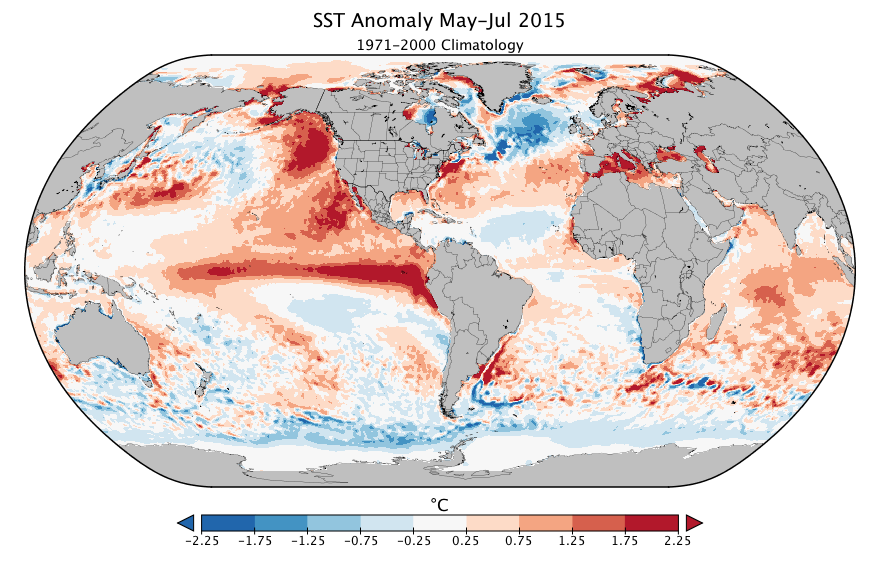

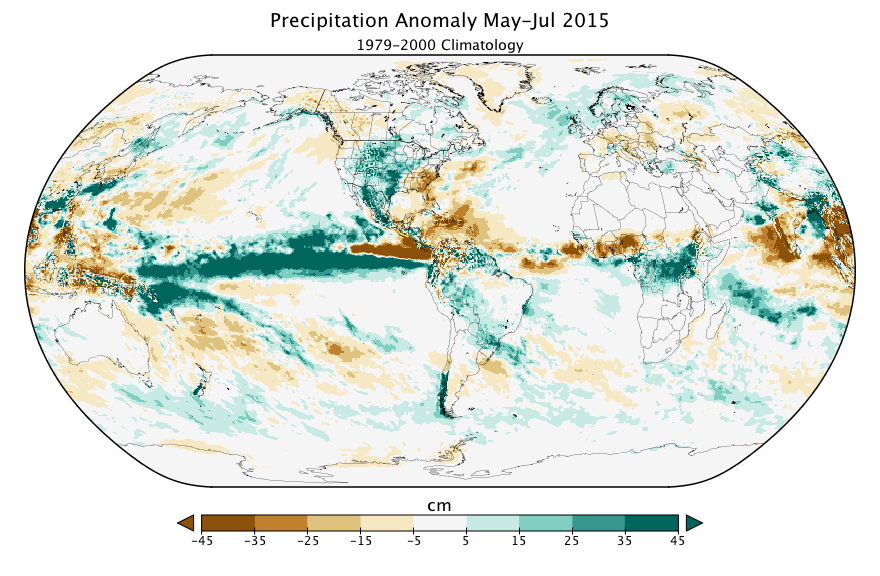

Figure 2. Global sea surface temperature and precipitation anomalies for May-July of this year. The prominent warm anomaly and precipitation surplus across the equatorial Pacific are associated with El Niño. Likewise, the broad warm anomalies off the western coast of North America are coupled with strong ridging in the atmosphere. The equatorial North Atlantic, in contrast, has near normal temperature and a precipitation deficit. Click on image to enlarge. Data source: NOAA OISSTV2 and NCEP CFSV2/CFSR.

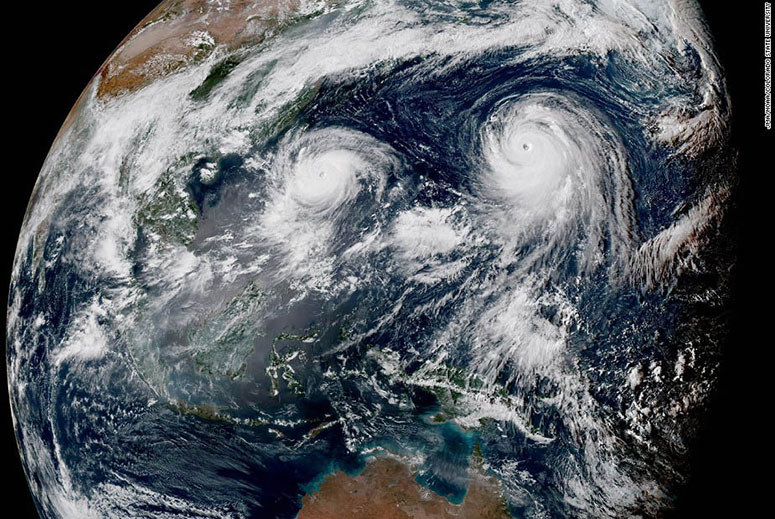

The anomalously warm surface waters from the developing El Nino have brought about what may be the most active tropical storm season on record across the northwest Pacific (The 2015 Northwest Pacific Typhoon Season: Already a Record-Breaker, RMS website) where there have already been five named storms reaching super typhoon status, >157 mph wind; Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind speed scale (2015 Pacific typhoon season, Wikipedia website). This is in sharp contrast to the situation in the North Atlantic, where relatively cool equatorial surface waters in addition to high wind shear aloft have inhibited the formation of major storms. On August 20, Tropical Storm Danny (Hurricane Danny Recap, The Weather Channel website) developed into a Category 1 hurricane (> 80 mph wind), the first of the 2015 Atlantic Hurricane season. Hurricane activity (Subject: G1) When is hurricane season?, NOAA Hurricane Research Division website) tends to peak in September and finish by the end of November. Thus, even after months of overall favorable weather in Maine, it is perhaps best to not get too complacent.

Figure 3. Satellite image showing typhoons Goni (left) and Astani (right) in the western Pacific on August 20, 2015. Image source: JMA/NOAA/Colorado State University.