Bulletin #1075, Tarping in the Northeast: A Guide for Small Farms

Bulletin #1075, Tarping in the Northeast: A Guide for Small Farms (PDF)

Authors:

- Natalie Lounsbury, Postdoctoral Research Associate, University of New Hampshire Department of Natural Resources and the Environment

- Sonja Birthisel, Faculty Associate, University of Maine School of Forest Resources and Ecology and Environmental Sciences Program

- Jason Lilley, Sustainable Agriculture Professional, University of Maine Cooperative Extension

- Ryan Maher, Research and Extension Specialist, Cornell Small Farms Program, Cornell University

The authors would like to thank Maeve Wivell, Molly Shea, and Sue Ishaq, for their research and writing contributions to this guide as well as the farmers who graciously shared information about their operations for the Case Studies, including Dave McDaniel and Heather Selin, Molly Comstock, Ben Stein, and Alicia Brown, Ryan and Kara Fitzbeauchamp, Daniel Mays, and John Hayden. Additionally, we would like to thank Becky Maden, Anu Rangarajan, Peyton Ginakes, and Johnny Sanchez for helpful reviews.

For information about UMaine Extension programs and resources, visit extension.umaine.edu.

Find more of our publications and books at extension.umaine.edu/publications/.

Introduction

Reusable tarps, including black plastic (silage tarps), clear plastic, and landscape fabric, are multi-functional, accessible tools that are increasingly popular on small farms. The use of opaque materials that block light is frequently called “occultation” while the use of clear tarps is called “solarization.” We treat “tarping” as a general term to include both. Regardless of the material used, tarps are applied to the soil surface between crops and then removed prior to planting.

Definitions

Solarization is the practice of using clear tarps to capture solar energy and heat the soil surface. The effects of solarization on pests (weeds and pathogens) and beneficial organisms are highly dependent on weather conditions.

Occultation is the practice of using opaque (typically black) tarps to block light and therefore prevent photosynthesis. The word has Latin origins, meaning “to block.” The effects of occultation are less dependent on, but nonetheless affected by, weather conditions.

In cool climates like that of the Northeastern US, tarping has emerged as an important way to manage weeds, crop residue, soil moisture, and nutrients. Tarps can be versatile tools left in place for days to months at a time depending on context. They are commonly seen as ‘placeholders,’ covering soils to keep them weed-free and to retain moisture and nutrients until planting time. Many farmers use tarps to reduce the intensity of tillage or the number of tillage passes, while other farmers have moved to rotational no-till or even continuous no-till with tarps. Tarps have also been deployed as a way to transition new fields into production.

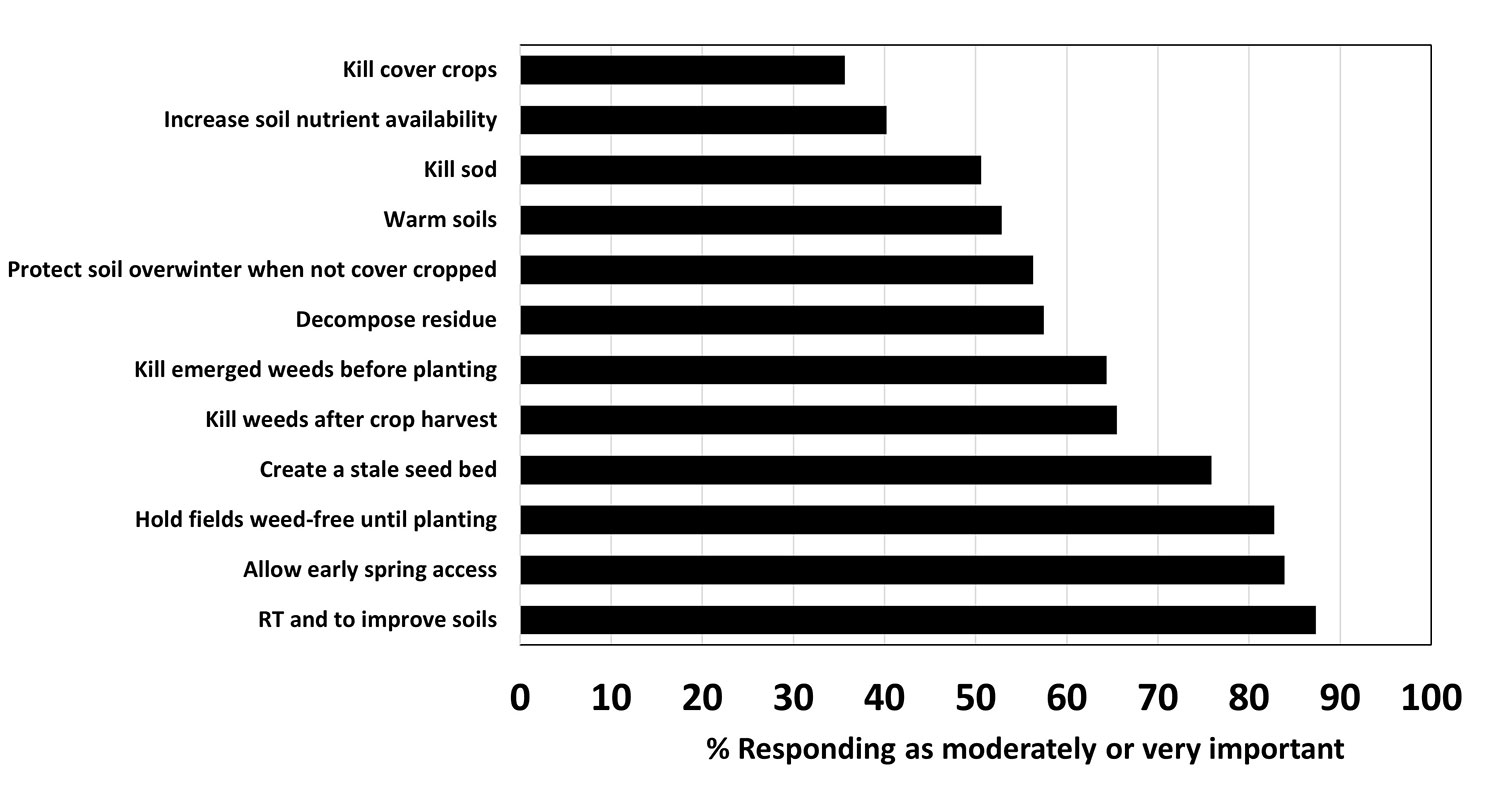

Farms using tarps are generally small (<5 acres) and employ organic practices, however, the reasons farmers use tarps are diverse. A recent survey of farmers in the Northeast (Rangarajan 2019) showed that there are many different goals with tarping.

Despite the advantages of using tarps, there are tradeoffs to this practice and many unknowns. Farmers cite the logistics associated with handling tarps, including moving, securing, and storing them, as especially challenging. Because of these challenges, tarping is currently scale-limited. Tarping is a powerful weed management tool, but some weed species can become problematic when tarping is deployed without additional or alternative weed management techniques. Occupying valuable field space during the growing season with a tarp on land that would otherwise be planted to cash or cover crops represents an opportunity cost, and the benefits of tarping must outweigh the time required to implement the practice effectively. While tarps are reusable, they are made of plastic; manufacturing, disposal, and plastic contamination during their use are concerns.

This guide is intended for those who are interested in or currently using tarps and would like to know more. The individual practice sections and farmer case studies serve as standalone resources. Research results and farmer experiences from multiple states in the Northeast have been combined to provide a thorough and up-to-date picture on the state of tarping knowledge including logistics, science, and economics.

Table of Contents

Types of tarps and how they work

General logistics of tarp management

- Tarp Size and Thickness

- Price Comparisons

- Securing Tarps

- Labor Requirements

- Longevity and Storage

- Drawbacks and Considerations

Tarping Practices

- “Stale seedbedding” with tillage and tarps

- Minimizing tillage with tarps

- Cover crop-based rotational no-till with tarps

- Continuous no-till with deep compost mulch and tarps

- Bringing sod into production

- Overwintering for early season production

Concerns with Plastic Use

Conclusions

Farm Case Studies

- Earth Dharma Farm ME — Stale Seedbedding with Tillage and Tarps

- Colfax Farm MA — Breaking Ground: Bringing Sod into Production and No-till Bed Management with Tarps

- Edible Uprising Farm NY — Overwintering Tarps: Cover Crop Based Tarping with Minimum Till

- Evening Song Farm VT — Cover Crop-based Rotational No-till with Tarps

- Frith Farm ME — High Input No-Till Permanent Raised Beds

- The Farm Between VT — Breaking Sod and Weed Management in Perennial Fruit Crops with Tarps

Works Cited

Acknowledgments

This publication was funded in part by the Northeast IPM Center through Grant #2018-70006-28882 from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), Crop Protection and Pest Management, Regional Coordination Program. Additional funding was provided through Northeast SARE Project LNE18-371, Northeast SARE project LNE19-382, USDA NIFA OREI 2014-51300-22244, USDA NIFA Agriculture and Food Research Initiative (Niles, 2018-68006-28098), USDA NIFA Hatch Projects 100682, 1004501 and 1013971, and the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station.

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2022

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

The University of Maine System (the System) is an equal opportunity institution committed to fostering a nondiscriminatory environment and complying with all applicable nondiscrimination laws. Consistent with State and Federal law, the System does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender, gender identity or expression, ethnicity, national origin, citizenship status, familial status, ancestry, age, disability (physical or mental), genetic information, pregnancy, or veteran or military status in any aspect of its education, programs and activities, and employment. The System provides reasonable accommodations to qualified individuals with disabilities upon request. If you believe you have experienced discrimination or harassment, you are encouraged to contact the System Office of Equal Opportunity and Title IX Services at 5713 Chadbourne Hall, Room 412, Orono, ME 04469-5713, by calling 207.581.1226, or via TTY at 711 (Maine Relay System). For more information about Title IX or to file a complaint, please contact the UMS Title IX Coordinator at www.maine.edu/title-ix/.