Interview with Dr. Stephen Kress

Atlantic puffin populations on several islands in the Gulf of Maine were decimated in the mid 1800s by hunters seeking meat, eggs, and feathers. In 1973, Dr. Stephen Kress began to restore these colonies by transplanting chicks to their former breeding grounds and emboldening them to return as adults and explore the island’s breeding habitat. The success of this program, Project Puffin, on an island called Eastern Egg Rock has led to the restoration of other coastal bird species and provided important data on the life stages of the Atlantic puffin. In this interview, Dr. Kress explains how the breeding phenology of puffins is connected to the productivity of the Gulf of Maine and the health of the marine ecosystem.

What caused you to become involved in puffin restoration and research?

I first met puffins on Machias Seal Island, the Canadian island. Then, I came to the Audubon camp on Hog Island as a bird life instructor and learned that there used to be puffins breeding on Eastern Egg Rock, which is about 8 mi from Hog Island. I decided that it was really a shame that people had eaten them all off of these islands and, therefore, we couldn’t see them. Wouldn’t it be great if I could restore that colony? I set about doing that starting in the late 60s. I thought it would take a few years to do that and here we are 41 years later, still at it. It was very successful because we stuck with it long enough and now it’s a new level of success because of what the puffins are telling us about the oceans, using seabirds as indicators of the kinds of changes that are important to everybody.

What are the typical breeding patterns of the Atlantic Puffin?

Puffins come to land to breed, usually, during the first week of April. The puffins only lay one egg each year, unlike many kinds of birds. They lay their egg, on average, about the third week of April. It takes six weeks for the egg to hatch and the incubation period is shared by male and female. Incubation is a fixed period; it takes the same amount of time every year, 42 days. But, we’re finding that the hatch date actually varies quite a bit from year to year and that was an interesting discovery.

How do environmental factors influence the breeding process?

Hatch date has a lot to do with the energetics of laying the egg in the first place because, for their size, the egg is a big egg. It’s a 60g egg, about the size of an extra-large chicken egg, but the puffin is a fraction of the size of a chicken. It actually comes out to about 15% of the female’s body weight. In order to lay that egg, they have to be feeding well, so there has to be plenty of food. Puffins reach a certain threshold body weight and certain breeding condition as a result of the amount of food. They are able to lay their egg earlier if they are in better breeding condition. Their condition for breeding varies somewhat from year to year depending upon the weeks prior to breeding when they are gathering energy for the egg to be laid. If they had a rough winter because there’s not much food in the ocean, they probably are not going to be in the best condition.

[Puffins can choose not to breed in years when food is not readily available. This is a way for a long-lived bird species to reserve energy for years when breeding is more likely to be successful, but too many years without breeding will negatively affect the population.]

What trends are shown by the data?

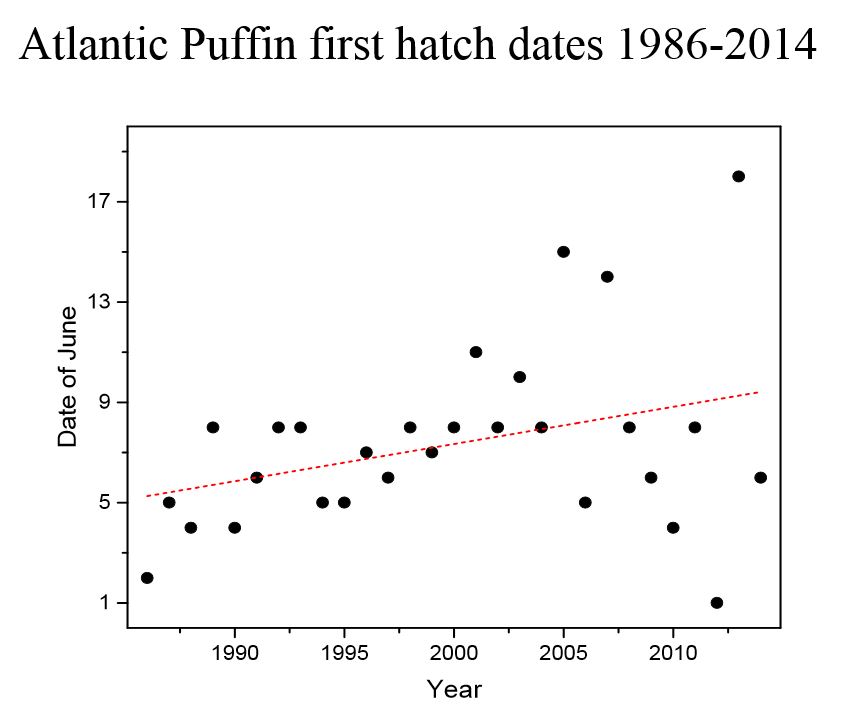

Up until about 2005, puffins were consistently hatching in the first few days of June. In general, the hatch is getting later and more irregular from year to year after 2005 and that may just be a result of the irregularity influencing the lateness, meaning those late years are swinging the average later, even though the bloom is getting earlier. Because they’re feeding up the food chain, the food they are eating – copepods, marine worms, crustaceans, small fish – all benefit from the spring [phytoplankton] bloom. The hatch date is correlated with the bloom. The earlier the plankton bloom was, the earlier the puffins’ hatch seemed to be.

A good example of that occurred in 2012; the spring bloom was early and that’s when we had one of our earliest hatch years for puffins. In years when there was an indistinguishable bloom, that is, you barely can find the bloom, the puffins were very late. That happened in 2013. About a third of them didn’t even lay eggs. For those that did lay eggs, it was the latest hatch of all. So, breeding phenology has to do, not just with the bloom, but whether there is even a bloom and the timing of that bloom.

[It is important to note that this data is specifically from Eastern Egg Rock, a small well-studied population of about a hundred pairs. It is not fully known how many other puffin colonies are displaying these same trends.]

How is knowledge of this relationship useful for scientists?

To me, what this really comes down to is that the puffins’ egg date is a reflection of the timing and the size of the spring bloom, which is one really great snapshot in knowing whether the rest of the food chain is going to prosper or not.

How is citizen science part of your research?

People can go to Explore.org and look on the “puffin burrow” cam. This time of year they will see archival video footage of what the puffins were doing underground. There are some fun videos! During the summer, usually from the middle of May to the middle of August, the puffin cam in the burrow is active. People see in real time what’s going on in the burrow and they’ll have an opportunity, if they want to, to make some observations and record them.

The burrow cam documents what kinds of fish, what time of day the feedings are and how frequent the feedings are. This gives us a better sense for not just what kinds of foods but how frequent the feedings are – that’s an important part of calculating how well they’re doing. You have to know literally how many calories of fish the chick got over the season to know how productive the ocean has been. These citizen science observations can help us measure.

There’s a camera above ground too. We find that just counting the number of puffins sitting on this one rock at a certain time tells us how productive the oceans are. If the puffins are sitting on the rock, it means they’re well fed and they don’t have to work very hard. So, if they’re home on the island, that’s a good thing. If there are not many on the rocks, that means they’re out at sea and are probably working hard to get the food. Just a simple head count is an indication of how well things are going and citizens can collect that at a standard time and standard location. We had over 2 million viewers in 218 countries watching our puffin and osprey cams last summer.

What message do you want readers to take away with them based on your work?

I would hope that people understand that our effects are widespread on this planet. There’s no place where people’s impacts are not felt. We can change one thing in one place and that affects things far away. Everything is interconnected. The puffin is part of that connectivity; it’s not just living on an island all by itself isolated from the impacts of people far away. Burning coal in Ohio, causing ocean acidification, is affecting puffin survivability here on the Maine Coast, for example. Overfishing of herring for lobster bait, so there’s not enough food in the ocean for the puffin to eat, is affecting puffins here. The puffins’ world is dependent upon the climate that we give it. Its ability to survive and our own ability to survive are all linked together.

*********************

Over the years, puffin restoration in the Gulf of Maine has developed two storylines. The first, restoring puffins to their former breeding grounds, is a tale of perseverance and success. This story, forty years in the making, has led down a new path. Data gathered from many years of monitoring is showing the effects of a changing environment on the restored colony. Puffin hatch dates have become more variable since 2005. Additionally, hatch dates appear to occur later on average, although significant variability in the data from recent years may be skewing the overall trend. The spring bloom has been occurring earlier, so, if chicks hatch later, there will be more time for juvenile fish to grow and greater challenge for parents to catch fish of appropriate size for their chicks to swallow whole. Warmer waters may also contribute to a lack of food as the ranges of pelagic fish species shift, forcing puffin parents to seek fish outside their chicks’ usual diet of herring and hake. Finally, as the ocean absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, the pH of seawater decreases – a process called ocean acidification – and the plankton bloom can be negatively impacted, further reducing food sources. Research has shown that puffin phenology can provide clues to the amount of food available and the overall health of the Gulf of Maine. If humans continue to monitor the puffins at Eastern Egg Rock and act to resolve the challenges that they warn us of, this second storyline can also have a positive outcome.

If you would like to learn more about Atlantic Puffins or become involved in restoration and monitoring, there are a number of ways to do so.

- View articles and information online at www.projectpuffin.org

- Visit the Project Puffin Visitor Center in Rockland (311 Main St.)

- Take a puffin watching tour from New Harbor or Boothbay to view the restored colony at Eastern Egg Rock

- Join Dr. Kress for a course at the Hog Island Audubon Camp- six day programs in birding and coastal conservation for adults, teens and families: http://hogisland.audubon.org

- Make a contribution or adopt a puffin online at www.projectpuffin.org