Expedition 4: How Do Scientists Know What Data to Collect and How to Collect It?

Catching up, looking ahead, and more scientific practices

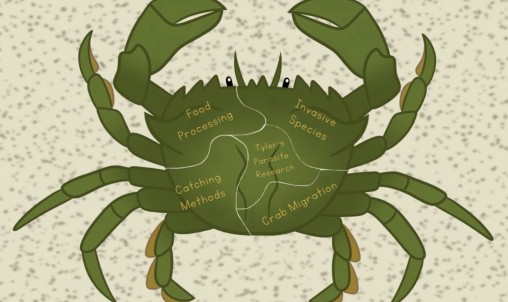

In last week’s video, Tyler described asking questions and defining problems to direct his focus on the problem of the invasive European green crab, and its relationship to the spiny-headed worm parasite that it has been found to carry. Another step in Tyler’s process was to gather and evaluate information from suggestions made in previous research studies and observations of past events to help develop some testable research questions.

This week, we revisit those questions as Tyler explains how they are used to make decisions about what data will be needed to help answer those questions, and making plans to identify the best locations and methods to gather those data. Tyler will discuss how he will be gathering and analyzing data, planning and carrying out investigations, and designing solutions to problems.

Like we have mentioned before, these are all practices of scientists and engineers. You might notice that some of these practices will show up more than once and rarely by themselves. This is because the practices are so connected to one another that it is difficult to imagine using only one without one or more others at the same time.

For example, if you saw a puddle of water in the middle of the floor (hopefully before you stepped in it), you would immediately start thinking about how it got there, coming up with possible explanations, planning some ways of testing those ideas, and more! It’s just what we do! It’s what makes us all scientists!

Like us, Tyler is doing what scientists do by using many of these practices to answer questions about the green crab in Maine.

Research questions and how they might be answered

Tyler is asking three questions:

- How many green crabs are carrying the spiny-headed worm parasite, and how does this number change across bioregions or 5-year time scales?

- Does the spiny-headed worm show up more often in certain variations of green crabs (age, size, sex, location, etc.)?

- How can we make sure that the capture methods we use are resulting in accurate data?

In order to answer these questions, Tyler will need to rely on observations of the crabs that his team collects from the field. He will also use the expertise and knowledge of other scientists and researchers to gather information that will be important to his study. It is putting these pieces of information together like a puzzle that helps progress our scientific knowledge and solve real-world problems.

What Do You Think?

Here are some questions to discuss with your class, or to investigate on your own!

- What topics have you learned about in your science classes recently that might apply to this green crab research?

- What innovative methods would you use to go catch green crabs on the beach?

- What other information would you like to learn about my research, in general?

- How do you communicate the information that you learn in science classes?

Have More Questions?

- Send us an email at umainefar@maine.edu.

- Join Tyler (@UMaineFAR_Tyler) live each week throughout his journey and ask your questions using #UMaineFAR. (Archived UMaineFAR Live Chats)

- Follow the adventure on Twitter (@UMaineFAR)!

- Visit the Follow a Researcher® website.

Other resources

- For more about NGSS and Scientific and Engineering Practices, see NGSS.

Join the next live chat on Thursday, May 17, 2018 at 1:00 PM (ET) by searching and using the hashtag: #umainefar.