Maine Home Garden News – April 2024

In This Issue:

- April is the month to…

- Transplanting Shrubs

- Spring Hunting for Fiddleheads

- Featured Volunteer Lydia Mussulman

- Backyard Bird – Brown-headed Cowbird

- Responsible Storm Cleanup Advisory

- Maine Weather and Climate Overview

April Is the Month to . . .

By Coral Sheldon-Hess, Androscoggin County Master Gardener Volunteer Intern

For most of the state, the “expected” last frost date is in May – of course, we can make no guarantees when it comes to weather — so April is the time to get tools ready and to direct sow a few cold-hardy plants.

Maintain your tools:

If you put your tools in the shed without sharpening, oiling, and otherwise performing maintenance on them last fall, you aren’t alone. But you will want them in top shape for the growing season ahead. The Illinois Extension has a two-page PDF about tool maintenance that may be helpful to you (and me).

Start seeds:

UMaine Extension’s “Starting Seeds at Home” bulletin #2751 lists the following plants for starting indoors in April: pepper, eggplant, broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, coleus, statice, impatiens, larkspur, cosmos, tomato, basil, marigold, and calendula.

Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners recommends starting the following outdoors in mid-April: beets, carrots, cilantro, dill, leaf and head lettuce, parsnips, peas, arugula, radishes, salad turnips, shallots, spinach, bunching onions for summer harvest, and onions from seeds or sets.

To help with your planning, the Extension has a handy planting chart with dates and distances between plants and rows, and they recommend this page for finding your expected last frost date.

Get rid of browntail moths:

Browntail moth caterpillars will start to emerge by mid-April, so this is your last chance to remove their nests. Identification resources and information about management techniques is available from the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry.

Enjoy the outdoors:

If the spring weather has you itching to get outside, here are some options: make sure to get out and safely watch the solar eclipse on the 8th, try a bird or plant walk with the Audubon Society, visit your closest botanical garden or arboretum (Wikipedia has at least a partial list), and for my fellow night owls, consider certifying and volunteering in “Big Night(s)” to save amphibians.

Be patient:

As tempted as we all are by the spring weather and so much sunlight, it might not yet be time to clean up our garden beds, because the debris is still serving as insulation for a wide range of insects including a variety of pollinator species. Consider holding off on mowing and leaving winter pollinator habitat, like those old stalks from fall’s woody plants and any leaves you conscientiously didn’t rake, where they are for just a little bit longer. The Xerces Society has signs you can put up, in case you’re worried about the neighbors judging you.

And a few tips from the past…

When designing your ornamental beds, consider the trend of including edible plants in decorative plantings. Rainbow Swiss chard or okra look equally at home in a flower bed or a vegetable garden! Rebecca Long, Sustainable Agriculture and Horticulture Professional

Pansies and violas are in garden centers, ready to give you some spring color. Put them around your entrances or in containers. They will be a welcome reminder of things to come. The late Diana Hibbard, former Home Horticulture Coordinator

Educate yourself on new invasive species. While you’re out looking for winter-damaged plants, make sure you check for evidence of predation and damage from other garden pests. Deer and rodents can be expected to cause a certain amount of damage each year, but we have a particularly aggressive Scandinavian newcomer cropping up in our Maine landscape, with the ungainly name of Nomea diminutiva Botanicalis. Utah State University’s Cooperative Extension has a great practical guide to control of the pest here.

— Jonathan Foster, Statewide Horticulture Outreach Professional (who wishes you a happy April 1st!)

Transplanting Shrubs

By Jonathan Foster, UMaine Cooperative Extension Horticulture Outreach Professional

The time comes in almost every home gardener’s life when you decide that a shrub is in the wrong place. Perhaps you planted it early in your gardening career and didn’t consider the conditions. Or maybe your landscape has changed in the intervening years and the conditions aren’t the same. Either way, it’s sometimes necessary to relocate an established shrub.

Consider the size of the job.

Root balls are extremely heavy and if you’re looking at one over 2’ or so in diameter, you should strongly consider hiring a landscape service with heavy equipment to do the job.

Verify site conditions.

Make sure the new location has the correct soil, light, water, and other suitable conditions for the shrub in question. The last thing you want to do is go through the trouble of moving the plant and wind up no better than where you started. It’s an excellent time to have your soil tested through the UMaine Analytical Soil Lab.

Mark your calendar.

Shrubs should be transplanted during dormancy, so aim for spring before new growth or fall after leaf drop (coniferous plants go slightly earlier, in August through September). The soil should be moist, but not sodden, and the plant should not be under any water stress.

Root pruning.

This is a tactic that can greatly improve the likelihood of successful transplantation. If you intend to move a plant with a root ball, pruning the roots in the fall for a spring transplant (best approach), or the spring for a fall transplant (watering during the summer crucial), induces a new flush of feeder roots in the root ball area. This helps hold the root ball together during the move and makes it easier for the shrub to reestablish itself in the new location. There are two methods. One, using a sharp spade and deep cuts, sever the roots in a circle around the plant in the size of the root ball you intend to move. Or two (better with more established shrubs), dig a trench around the plant in the same area and fill it with rich growing medium–this encourages feeder roots to grow into the new area, and they should be moved with the root ball (they should be easier to tease out of the looser medium in the trench).

Bare root transplanting.

Bare root transplants should only be attempted with very young plants; it is the easiest method, but can have the highest mortality rate. Gently tease out the primary root system and wash it clean. Because dehydration of the roots is the primary reason for failure, either plant in the new site immediately or keep the roots wrapped in wet peat moss or mulch until it’s time to do so. The hole dug in the new location should have a little mound at the bottom that the plant can be rested on and the roots arranged outward in the space. Gently fill in soil around the roots and firm in with your fingers to make sure the roots are covered and supported.

Root ball transplanting.

For most shrubs, you’ll be moving a ball of soil that is bound together with roots. Again, you’ll go around the base with a sharp spade, then angle it inward under the root ball to sever the roots at the very bottom. Tip the shrub to one side, lay burlap down in the hole, then tip the shrub the other direction to pull the burlap up and around the root ball. Tie the burlap around the ball with twine and move the shrub to the new location (a tarp can help slide it over distance).

The new location.

Dig the hole twice as wide as the root ball, but only deep enough to set the plant in at the same depth–marking the shrub stem at ground level before digging it up can help you orient it accurately. Do not plant it deeper than it was, fill the hole with your medium, cut away any portions of the burlap still visible, and water the shrub thoroughly. Monitor the moisture level throughout the new growing season, maintaining consistent water and avoiding both over-and underwatering.

Read complete transplant guides from the University of MN Cooperative Extension and Clemson University Extension.

Spring Hunting for Fiddleheads

By Lynne Holland, Horticulture Professional

This year, many of us will be looking up to the sky for the Eclipse on April 8, 2024. But every spring, people are walking the woods and looking down for fiddleheads.

Dave Fuller, a retired educator from the University of Maine Extension, is the author of our Bulletin #4198 Facts on Fiddleheads and we have shared that many times. This spring make room for new voices on this topic such as this blog from Kitchen Vignettes on Maine Public. In late April, make time for the Fiddlehead Festival on Saturday, April 27 from 10-3 on the campus of the University of Maine at Farmington. Nothing says spring goodness like fiddleheads.

Featured Volunteer Lydia Mussulman

By Naomi Jacobs, Penobscot County Master Gardener Volunteer

This month’s featured Master Gardener Volunteer is 80-year-old Lydia Mussulman of Hermon, who came to Bangor 31 years ago when her husband took a job with the Maine Soil Conservation Service. In previous years, they had raised three kids while living in eight different cities and a dozen different houses. With such frequent moves, she never had the opportunity to garden. But after visiting a friend’s inspiring garden in New Hampshire, she vowed that once the kids were gone, gardening was what she wanted to do.

The move to Maine let her carry out her resolution. Their new home on outer Essex Street had five acres but no landscaping to speak of. Lydia promptly signed up for the second-ever Master Gardener Volunteer training. Twelve years later, the property had eighteen beds planted with flowers and herbs, to say nothing of sheep, ducks, and her husband’s vegetable garden. Their next home, in the city proper, presented a smaller blank slate which Lydia quickly filled with ornamental plantings.

In her first years as a Master Gardener Volunteer, Lydia learned as a “floater,” assisting experienced volunteers in whatever needed to be done at the Rogers Farm Demonstration Garden. Eventually, she took charge of a large plot, where she designed and executed several different gardens. These include an alpine garden featuring over 50 different plants, an Asian garden, a classic perennial garden, and most recently a bee garden emphasizing late-season blooms to help pollinators prepare for hibernation. Her wide-ranging interests include not only garden design and growing techniques, but historical topics such as the Nine Sacred Herbs of the Anglo-Saxons, medieval strewing herbs, and Victorian tussy-mussies (small nosegays). She has always enjoyed diving deeply into a subject, creating projects grounded in her new knowledge, and then moving on to a fresh challenge.

She has a particular affinity for design. One of her most extravagant projects at Rogers Farm was an all-lettuce garden, inspired by an ornamental vegetable garden that she’d seen on a trip to England. Using a range of lettuce varieties with different colors and textures, she designed elaborately patterned beds resembling a Victorian floral parterre.

Currently, she is designing another new home garden and thinking about yet another redesign for the Rogers Farm plot. She also maintains the entrance plantings at the Bangor YMCA. While tending that garden, she enjoys meeting the people who stop to ask questions or just to chat.

Lydia feels that anyone who is “really serious about learning to garden” should sign up for the Master Gardener Volunteer training. She encourages parents to “get your kids involved; bring them to the activities at Rogers Farm if you have the time.” Children can also benefit from helping to design and tend a home garden. And to older gardeners like herself, she recommends yoga classes to stay flexible and strong.

Lydia is a great example of a Master Gardener Volunteer who follows her passions, loves to share her knowledge, and creates much beauty for our community.

Backyard Bird – Brown-headed Cowbird

By Maine Audubon Field Naturalist Andy Kapinos

Brown-headed Cowbirds are easily overlooked among the flocks of returning blackbirds in early spring. They are similar in shape and size to Red-winged Blackbirds, and the males of both species are mostly black. Male Brown-headed Cowbirds have no red or yellow on the wing and a brown head. Females look completely different; they are a sandy tan all over with a whitish throat patch, like a slightly larger, less-striped female House Sparrow.

Seeing these two distinct plumages together in the same group is a good clue that you are seeing Brown-headed Cowbirds, since most other blackbird species are less dimorphic. Clear contrast is another common way many people see cowbirds in their backyard: begging for food from a parent of a different species, often a much smaller sparrow or warbler. Brown-headed Cowbirds are well-known brood parasites, with females laying eggs in other birds’ nests and leaving them to be cared for by the host species.They evolved this tactic in their ancestral habitat, following bison herds around the Great Plains, which gives them their other common name, “Buffalo Birds.”

Since the herds were constantly on the move, cowbirds never had time to build nests, but they could deposit eggs in existing nests while they were stopped near a thicket. They spread east as European colonists destroyed forests and replaced them with fields and livestock, unwittingly replicating aspects of Brown-headed Cowbirds’ original habitats. Now they can be found in open habitats throughout Maine, where they feed on seeds and insects, often near thickets and hedges that offer cover and potential nests to parasitize. If there are cows or horses near your backyard, you may even see a flock of Brown-headed Cowbirds perched on their backs, like they would have on the bison herds of the Great Plains.

Responsible Storm Cleanup Advisory

Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry

After power and other utilities have been restored, property owners often face the challenge of what to do with storm-damaged trees. To assist with this, Project Canopy, a Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry (DACF) and Maine Forest Service (MFS) program, offers valuable guidance and helpful tips to property owners with questions about handling downed trees, limbs, and branches.

Trees and Branches Around Homes and Power Lines:

Homeowners are encouraged to promptly address downed trees and branches, especially those affecting homes and power lines.

For trees entangled with power lines, it is essential to contact local power companies for assistance. Even if a fallen limb is not near power or utility wires, it’s advisable to rely on professionals to assess the extent of the damage before attempting repairs or removal. For trees or large branches threatening or impacting homes or businesses, enlist the help of a reputable licensed arborist to take care of the cleanup.

Injured Trees Requiring Climbing or Chainsaw Work:

In cases where storm-damaged trees require climbing or chainsaw work, homeowners are urged to work with licensed arborists. Arborists in Maine are required to be licensed. A license indicates that an individual is properly trained, has passed exams, and holds the required insurance. Arborists are trained tree care professionals with the skills to evaluate and rectify storm-damaged trees. They can determine how much of a tree can or should be salvaged. Beware of fly-by-night emergency tree-cutting services, and always request proof of licensing, insurance, and references. The DACF Division of Animal and Plant Health Arborist Program provides more information about working with arborists.

Protecting Maine’s Forests:

The Maine Forest Service stresses that woody debris from storm damage may harbor harmful insects or diseases that threaten our forests. Transporting this debris can unintentionally spread pests to new areas.

- In addition to the risks it brings to our environment and economy, violation of rules governing debris movement jeopardizes eligibility for federal aid in the event of a disaster declaration.

- Be aware of Maine’s four State forestry-related quarantines and the additional federally regulated quarantine pest. The quarantines may impact the movement of some woody storm debris, such as ash trees from within the Emerald Ash Borer Regulated Area, larch from areas within the European Larch Canker quarantine, and hemlock branch or top material from regions within the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid quarantine. Use this searchable town list, to determine quarantine status: Quarantine Information: Forest Health and Monitoring. CSV files are available as downloads for use in GIS software.

- Severe storms can also reveal the presence of invasive forest pests like the Asian longhorned beetle or hemlock woolly adelgid. If you suspect damage from such pests, take photos and share them with the MFS to aid in pest management efforts.

Storm Preparedness Resources:

In addition to responsible storm cleanup, being prepared for future storms is vital. Here are some resources to help you stay informed and ready:

- Maine.Gov Alerts: Subscribe for storm warnings, bulletins, and other urgent updates.

- FEMA and MEMA: Connect with county and local emergency management contacts and stay updated via social media.

- Small Business Administration (SBA): Find guidance and support for businesses before and after emergency events.

- Maine Prepares Resources: Explore home, business, and community emergency planning.

For media inquiries or additional information, please contact: Jim Britt

Maine Weather and Climate Overview

Dr. Sean Birkel, Assistant Extension Professor, Maine State Climatologist, Climate Change Institute, Cooperative Extension University of Maine. For questions about climate and weather, please contact the Maine Climate Office.

NOAA statewide temperature and precipitation data for Maine show that winter (December–February) 2023/24 ranks 2nd warmest (just below 2016, which was 1st warmest) and 39th wettest (70th percentile) for records beginning 1895. It has now been nine years since the 2014/15 winter season, which was the last time average December–February temperature fell below the 20th century climate baseline. March has also been very warm. The means of daily surface observations (March 1–26) in Bangor, Caribou, and Portland, rank 7th, 6th, and 9th warmest, respectively. It’s also been very wet, with accumulated precipitation (March 1–26) for the same sites ranking 4th, 15th, and 5th wettest.

As of the morning of March 28, a storm system tracking northward along the East Coast is producing significant rainfall, with 2–3 inches (perhaps locally more) forecasted before the month ends. This will boost the month precipitation rankings, and some locations could see the wettest March on record. Prior to a snowstorm on the 23rd–24th (with rain, sleet, and freezing rain across the coastal climate division), much of the state had an extended period of bare ground with number of days without snow ranking in the top 10. Likewise, many lakes have seen record or very early ice-outs this year, especially in the southern half of the state. In all, these conditions are reminiscent of the early onset of spring in 2010.

Worldwide weather has been influenced by El Niño conditions in the Pacific since June, 2023. In December, the El Niño peaked, ranking 5th strongest based on the Oceanic Niño Index for records beginning 1950. Moderate to strong El Niño events tend to produce winter weather patterns that bring above normal temperature and precipitation to Maine – and this is what we have seen overall this season, but with the exception of a dry February. El Niño is the warm phase of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO). The NOAA Climate Prediction Center forecasts a transition from El Niño to ENSO-neutral conditions between April and June, after which there are increasing odds of La Niña developing through the summer.

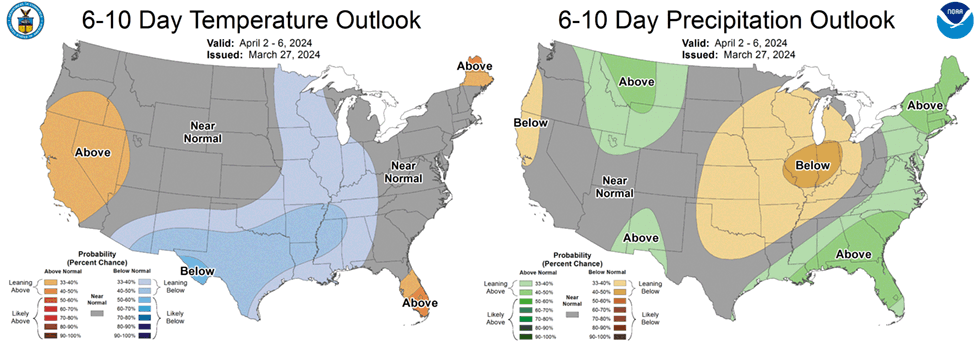

| Product | Temperature | Precipitation |

|---|---|---|

| Days 6-10: April 2-6 (issued March 27) | leaning above normal | leaning above normal |

| Weeks 3-4: April 6-19 (issued March 22) | leaning above normal | equal chance |

| Seasonal: April, May, June (issued March 21) | leaning above normal | equal chance |

Be sure to check weather.gov for the latest weather forecast in your area. For winter weather updates, visit the National Weather Service Gray and Caribou forecast office webpages. For additional climate information, including historical temperature and precipitation data, visit the Maine Climate Office website.

Do you appreciate the work we are doing?

Consider making a contribution to the Maine Master Gardener Development Fund. Your dollars will support and expand Master Gardener Volunteer community outreach across Maine.

Your feedback is important to us!

We appreciate your feedback and ideas for future Maine Home Garden News topics. We look forward to sharing new information and inspiration in future issues.

Subscribe to Maine Home Garden News

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications, click on the Subscribe button below.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

For more information or questions, contact Kate Garland at katherine.garland@maine.edu or 1.800.287.1485 (in Maine).

Visit our Archives to see past issues.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around Maine. The following staff and volunteer team take great care editing content, designing the web and email platforms, maintaining email lists, and getting hard copies mailed to those who don’t have access to the internet: Abby Zelz*, Annika Schmidt*, Barbara Harrity*, Kate Garland, Mary Michaud, Michelle Snowden, Naomi Jacobs*, Phoebe Call*, and Wendy Robertson.

*Master Gardener Volunteers

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2024

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.