Maine Home Garden News – August

In This Issue:

- August Is the Month to . . .

- Think First…Spray Last!

- Pollinator Ponderings: Stellar Summer Native Plants

- Book Review: Glorious Shade

- Profiles in Urban Agriculture: Growing an Urban Orchard

- Backyard Bird of the Month: Red-bellied Woodpecker

- Maine Weather and Climate Overview

August Is the Month to . . .

By Kate Garland, Horticulture Professional

Apply for the next Master Gardener Volunteer Training! Applications are open now through August 15, 2025, at 4:30 p.m., and training begins in October. This popular program combines in-depth horticultural education with meaningful community service. Prefer to learn without the volunteer commitment? Check out the Maine Gardener Training also starting in October.

Harvest and cure onions and garlic. When the lower three leaves on garlic have turned brown, or when 70-80% of onion tops have fallen over, it’s time to harvest and begin the curing process. Curing is the process of allowing the outer tissue to dry thoroughly in a well-ventilated space, such as a shed or porch, before placing it in storage.

Share your harvest or lend a hand! Programs like UMaine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Harvest for Hunger and Good Shepherd Food Bank’s Mainers Feeding Mainers connect thousands of pounds of fresh produce to food security organizations across the state, but the need is still far greater than what’s available. Every bit matters and there are volunteer opportunities in nearly every community for those who want to help.

Cut annual flowers to promote continuous blooms. When flowers are left uncut, plants shift energy toward producing seeds instead of new blossoms. Regularly cutting flowers encourages more blooms throughout the season. Snip stems just above a node (where the leaves meet the stem) to keep plants tidy and productive.

Hand pick Japanese beetles. Research shows that hand-picking Japanese beetles and dropping them into soapy water can help reduce feeding damage when done regularly. The best time to pick is in the early morning or late evening when the beetles are less active. While this method won’t eliminate the population, it can be an effective part of an overall management strategy in home gardens.

Enjoy a cup of sumac lemonade. The fuzzy, red fruit clusters of staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina) can be used to make a refreshingly tangy seasonal drink. Steep the fruits in cold water, strain, and sweeten to taste for a naturally tart lemonade alternative.

Prepare for salsa and sauce season. Tomatoes, peppers and herbs are ripening, but if you do not have as much as you’d like for your upcoming canning goals, now is a great time to plan ahead. If you don’t have a large harvest of your own, consider purchasing in bulk from local farmers. Working with peak-season produce is a rewarding way to savor summer.

Sow a cover crop to build healthier soil. Field peas and oats are great choices for planting in August or early September. They grow quickly, die back over winter, and leave behind organic matter that benefits the soil. Scatter seeds over bare areas, rake or tamp them in, water well, and keep the soil moist until they sprout.

Keep planting vegetables. It’s not too late to directly sow salad turnips, carrots, spinach, lettuce, chard, kale, and beets. To help small-seeded crops retain moisture during dry stretches, place a piece of lumber or another covering over the newly seeded area for three to four days immediately after sowing and watering.

Create art in the garden and from the garden. Try pressing flowers, painting en plein air, making cyanotypes, or using natural pigments to color. These activities deepen your connection to the plants around, offer the opportunity to see landscapes through a new perspective and allow you to enjoy the beauty beyond the growing season.

Propagate woody plants from semi-hardwood cuttings. Late summer is a great time to try propagating certain trees and shrubs like dogwood, viburnum, or hydrangea. Semi-hardwood cuttings are taken from partially mature stems and can root successfully under the right conditions. Use a clean, sharp tool to take cuttings, dip them in rooting hormone, and keep them in a humid environment out of direct sunlight while they root.

Take cuttings of annuals and tender perennials for next year’s garden. Plants like coleus, geraniums, and sweet potato vine can be propagated from cuttings taken now. In spring, you’ll have healthy, established plants ready to return to the garden.

Make the most of the fair season! Maine’s agricultural fairs offer a fun way to connect with the people, plants, and animals that shape our state’s farming culture. From livestock exhibits to garden displays, there’s something for everyone to enjoy. Take advantage of these events to learn, celebrate, and gather new ideas.

Think First…Spray Last

By Gary Fish, State Horticulturist Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry

Blooming ornamentals….fragrant, colorful and a visual delight. Flawless fruits and vegetables….robust in size, color and flavor. Picture-perfect lawn…deep green, weed free and evenly cut. These are dreams of those who garden.

Few gardeners’ aspirations are not intruded upon by nature. Some challenges sport hospitable names like dandelion and lambsquarter while others–grubs, borers, apple scab and black spot– sound downright sinister. But many people feel the presence of any pest means one thing: life-threatening damage is underway. The fruits of one’s labor have become a feast for the unwanted guest, and the gardener must decide whether to take action to control the problem.

In today’s world of convenience, many are quick to defend their dream gardens with bug sprays, weed killers, or disease controls. After all, these products claim solutions to the problem at hand. And since they are sold over the counter at the local hardware, grocery or department store, these products must be completely safe. Right?

Hardly! Science and the law recognize products with such claims as pesticides. And pesticides, by their very nature, are designed to be toxic–that is, poisonous–to one or more target pests. No pesticide is completely safe.

Pesticides: More Common Than Perceived

The word pesticide usually conjures images of agriculture or crop dusting when, in reality, pesticides are used routinely by nearly everyone who encounters pests. Pests belong to a catalogue of species as vast as the science of biology itself: from disease-bearing rodents to unsightly humidifier slime with scores of insects, weeds, fungi and germs in between. A pesticide is merely a mixture used to control these organisms once they negatively affect our environment.

Some pesticides are obvious such as the insecticides sevin and malathion. D-ConTM is a rodenticide; RoundupTM, an herbicide; and Captan, a fungicide. But many products are not recognized as pesticides by their users. Scott’s Turf BuilderTM, a “weed and feed” product, contains herbicides. Ortho Rose and Flower CareTM is a combination of fungicide and insecticide. Disinfectants LysolTM and ChloroxTM bleach are pesticides that kill bacteria. Mildewcides are commonly found in paints. Biological pesticides include Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt.) or Beauveria bassiana. Even tried-and-true products approved for organic growers, such as spinosad or pyrethrum, are pesticides because they claim to kill insects. By now, you’re asking, “Is anything safe, even the organics?” Nothing is completely safe, not when it comes to pesticides!

The Applicator’s Checklist

Avoiding use of a pesticide altogether is the most effective way to reduce health and environmental risks. Only consider a pesticide when other avenues of control have failed. Follow this checklist before you apply.

✔ Evaluate the situation. Determine exactly what pest is causing the problem. Local resources like Cooperative Extension or licensed pest control companies are available to assist with pest identification. Without this knowledge, the right tool for control will be elusive.

✔ Know the pest. Once you have identified the pest, zero in on its most susceptible stage. Application timing is critical. Control insects when they are small and more vulnerable. For example, don’t attempt to control crabgrass, an annual, late in the summer after the plant has produced thousands of seeds and has naturally begun to die.

✔ Take measurements. Before you go to the garden center to make a purchase, know how much area needs treatment. Purchase only what is needed right now, this season. Stockpiling pesticides creates greater potential risks for families and the environment.

✔ Choose products wisely. Look for products that are easy to handle such as granules and ready-to-use liquids. Concentrates require mixing, which can be risky business.

✔ Read the entire label before purchasing. Be sure the plant and pest are listed on the label. Check the “days to harvest” section. If the “days to harvest” is 21 days and you’ll be picking next week, don’t buy that pesticide. Determine what application and personal protective equipment is required. Don’t leave the store without all the needed equipment.

✔ Follow instructions. Read the label to determine the proper mixing strength and how much mixture to apply over a given area. Never add a little extra for good measure. Some herbicides work better at lower concentrations because they enter the whole weed and kill the entire plant. Adding extra burns off the top of the weed and allows a new plant to grow back. Mix only what is needed. Practice spray applications with water ahead of time to be sure the right amount will be applied.

✔ Look for sensitive sites. Check around the treatment area and remove toys, laundry, pet bowls or anything else that shouldn’t be treated. Prevent water contamination. Stay away from wells, ledge, sandy soils and open water. Don’t apply a pesticide to a bare slope or just before heavy rains are expected.

✔ Watch the wind and temperature. Applying pesticides in high winds is a waste of time and money and could contaminate sensitive sites. Winds should be under five to eight miles per hour but not perfectly calm. Keep the spray close to the target and spray in the direction of the breeze. Don’t apply when the temperature is greater than 65 degrees. Many pesticides are volatile and will not reach the intended target when used on hot days.

✔ Spot treat. If a pesticide must be used, only treat the infested area. Broadcast treatments waste pesticide and may harm beneficial organisms. Keep in mind the plant’s condition. Some insecticides may burn or kill plants that are stressed. Many pesticide labels warn against the potential for “phytotoxicity” or toxicity to plants.

✔ Finish it right. Keep people and pets away from treated areas until the re-entry time on the label elapses. Check for thorough coverage. Apply any left-over mix to another appropriate site. Don’t dump anything down the drain or on the ground. Application according to the label directions is always the best “disposal” method. Follow the label instructions for container disposal. Don’t just send them to the dump. Call the Board of Pesticides Control for guidance at 207-287-2731.

✔ Be patient and keep records. After treatment, wait long enough for the product to work. Some like Bacillus thuringiensis and glyphosate may take up to two weeks before completely killing the pest. Repeating the treatment before then would be a waste and an unneeded addition of pesticide to the environment. If the treatment doesn’t work, only repeat if the label allows re-treatment. Keep records of what was used and how well it worked. Records help you plan for the next application and prevent repeated mistakes.

Why Risky Pesticides are Legal

Before any pesticide product ends up on the hardware store shelf, it undergoes batteries of tests to determine negative effects on humans and the environment. With these data in hand, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency weighs the compound’s risks to people, pets and the environment. If those risks do not exceed established safety factors to protect children or people with challenged immune systems, the pesticide is registered, permitting legal use only according to label directions. Registration does not endorse the product’s safety; rather, it only means that if the pesticide is applied according to label directions, the risks of use based on current knowledge do not exceed the guidelines established by Congress in the Food Quality Protection Act of 1996.

Benefits vs. Risks

What are the benefits of pesticide use in the home garden? The primary benefit, often frowned upon by advocates against pesticides, is aesthetics. Homeowners simply want lawns weed-free and trees bright green and healthy. More tangible benefits include bountiful harvests, reduced spoilage of fruits and vegetables in storage, and protection from biting or stinging insects. These benefits spur gardeners to purchase and use pesticides.

But when considering a pesticide to derive these benefits, one needs to also think about the product’s potential risks to the user, other people and the environment.

Public health officials measure risk with a formula that accounts for toxicity and exposure. For example, entering a nuclear reactor wearing a special protective suit poses little risk compared to living unprotected for many years in a house filled with radon gas. Constant or repeated exposure to low levels of almost any toxin may result in negative effects.

Health and environmental risks from pesticides result from improper use. At risk are children, neighbors, pets, treasured plants and even ourselves. Even products used as alternatives to conventional pesticides, such as organics or biologicals, pose risks.

Spinosad applied to flower blossoms will kill pollinators. Pyrethrins inhaled by unprotected gardeners cause uncontrolled coughing and could trigger an asthma attack. Don’t be fooled by the “au naturel” marketing gimmick. Many of the most toxic substances on earth are natural or organic. Only a few drops of the organic pesticide nicotine sulfate can kill. Allergies to any type of pesticide will cause reactions, regardless of their source, natural or synthetic.

Gardeners who want a dream garden without the chemical nightmare must be sure that the benefits of pesticides outweigh the risks.

What About Home Remedies?

Salt, vinegar, soaps, and essential oils are often touted as easy and safe alternatives to pesticides. However, home remedies are not recommended. Many of the recipes found online are either unsafe, ineffective, or both. For example, vinegar-based solutions may provide short-term control by damaging the foliage of weeds, but they typically have little effect on the roots of perennial weeds, which will regrow. In addition, horticultural vinegar is a strong acid and can pose risks to the applicator by causing skin burns, eye injury, or respiratory irritation if used improperly. Always choose pest, weed, and disease management methods that are supported by science and approved for safety and effectiveness.

What Can You Do?

Look for plant varieties resistant to pest problems. Make sure a pesticide is genuinely needed. Ask yourself, “Is this really a problem?” Instead of a pesticide, use cultural or sanitary controls: pull the weeds, remove diseased plants, improve growing conditions. Prevent or control weed, insect or disease problems by placing plants in proper sites or by pruning overgrown specimens. Fight bad bugs with good bugs! Use or encourage beneficial insects and microbes by raising companion crops or by minimizing pesticide use.

If you must use a pesticide, read the application checklist and remember the Board of Pesticides Control motto: Think first…Spray Last.

Pollinator Ponderings: Stellar Summer Native Plants

By Allan Amioka, York County Master Gardener Volunteer

With around 1500 species listed as native to one or more of Maine’s five ecological regions, there is no shortage of stellar species which have evolved to play a beneficial role in our state. Their beauty is of value primarily to humans, but certain species support more Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) and bees than others. These insects (especially in the larval stage) are of critical value to birds and other wildlife. In recent decades we have learned more about the benefits of native plants thanks to the research of Dr. Douglas Tallamy and his team at the University of Delaware. Documenting the vastly greater variety of insects that are supported by native plants than by non-natives, they identified a small number of “keystone” trees and perennials that play a crucial role in the web of life. Oaks are the champions among trees, supporting over 400 caterpillar species. Asters and Solidagos (goldenrods) take top honors among perennials. Many insects are picky eaters and according to Tallamy, just 14% of native plant species are responsible for supporting 90% of native butterflies, moths and bees. Furthermore, some keystone trees, such as oaks, pines and chestnuts, are also among the best carbon sinks, meaning that they store more carbon than they release. The shade they provide is another benefit to humans and the ecosystem.

So how can we find native plants for our gardens, given that the market tends to be flooded not only with non-natives but with versions of native plants that might have fewer ecological benefits? These cultivars and their native equivalent, nativars, have been bred for desirable qualities such as disease resistance, smaller size, or unusual colors and shapes, but such changes can affect a plant’s ability to feed pollinators or caterpillars. Double flower forms, as well as changes to leaf and petal color–especially if dramatically different from the original–may be less attractive to insects or may compromise a plant’s ability to perform as they had evolved to do.

Also, most commercially available plants are asexually produced as clones of the cultivar. This ensures a consistent, repeatable product akin to a manufactured, production line item that minimizes surprises. Thus, in restoration settings or if you want to encourage genetic diversity in plant populations, straight open-pollinated species are preferred.

Having said that, one study found that a cultivar of Culver’s-root (Veronicastrum virginicum) called ‘Lavendelturm’ recorded a higher level of visits by pollinators than its species parent (see resource 2). The bottom line is that each cultivar/nativar should be evaluated on a case by case basis. Still, seeking out the true native plants is worth the trouble, for the fun of growing something your gardener friends haven’t seen before, as well as for the satisfaction of knowing you are supporting your local ecosystem.

You can recognize a cultivar/nativar by the plant’s title, which typically includes a catchy name in single quotes at the end. For example, New England Aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae) ‘Alma Potschke’ is a bright pink cultivar of the native pink/purple New England Aster. ‘Alma’ is lovely, but attracts fewer pollinators than her parent (resource 2).

Gardening with native plants is truly a case of “If you plant it they will come”. Prior to planting the red cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis) I grew from seed, I’d rarely seen hummingbirds where I live. Once the cardinal flowers were present, we were treated to long visits multiple times a day. One of the many great joys of any (predominantly) native garden is the abundance of pollinators and other wildlife. The natives aren’t always as showy as the cultivars but they have a delicate beauty all their own. And along with the wondrous buzz, hum and richness of life within, their constantly shifting textures, patterns and colors provide a never ending stream of sights and stories to look forward to.

Here is a partial list of plants to look out for. For more info, consult the list of Keystone Species at the National Wildlife Federation site and the Native Plant Trust’s list of “Pollinator Powerhouse Plants” that support a proportionally large number of caterpillar species.

Featured Keystone Species

Source: National Wildlife Federation

(Number in parenthesis = number of caterpillar species hosted)

[Number in brackets = number of pollen specialist bees supported]

Trees

Oaks (Quercus) – (436)

Cherries, plums (Prunus) – (340)

Shrubs

Blueberries, cranberries (Vaccinium) – (217) [14]

Willows (Salix) – (289) [14]

Flowering Perennials

Goldenrods (Solidago) – (104) [42]

Asters (Symphyotrichum) – (100) [33]

Plants Featured in the Collage

Those marked with an * indicate “Pollinator Powerhouses” because they serve as host plants for at least 15 species of caterpillars. All of the following plants have an affinity for sun-part shade with the exception of butterfly milkweed, yarrow, and narrow-leaved mountain mint which do best in full sun.

Common Boneset* (Eupatorium perfoliatum) A Maine native of special value to native bees, attracting butterflies as well. Provides seed for birds. Grows in drainage ditches, moist meadows. Wet soil.

Sundial Lupine* (Lupinus perennis) An early blooming Maine native in shimmering blues, purple and whites that the bees, butterflies and other pollinators love. Though extirpated (functionally extinct) in the wild due to habitat loss, this is a wonderful garden plant and sole host plant to the Karner Blue Butterfly. Being a legume it fixes nitrogen, which benefits the soil. Dry, sandy soil.

Note: Large-Leaved Lupine (Lupinus polyphyllus) is a native of the Western US. Taller, with a wider range of colors, and preferring moist sites, it is considered invasive in New England. This is the plant we see flowering in large colonies in open fields in June. For an excellent explanation of how to distinguish the native lupine from the Western lupine, see this Wild Seed Project video.

Northeastern Beardtongue* (Penstemon hirsutus) White to pale lavender flowers, early summer bloom. It’s fun to watch bumble and other bees wiggle their way into the tubular flowers seeking nectar. Durable, low maintenance. Average to dry soil.

Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) Host plant for monarch butterflies. Great nectaring plant. Does not spread by underground rhizomes like common milkweed and has a brighter colored flower. Average to wet soil.

Butterfly Milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa) Host plant for monarch butterflies. Great nectar plant, deep taproot, showy with bright colors of orange, red and yellow. Does not spread by underground rhizomes like common milkweed so makes a beautiful garden plant. Average to dry soil.

Spotted Joe-Pye Weed (Eutrochium maculatum) Great plant for native bees and butterflies, provides seed for birds. Grows in drainage ditches, moist meadows. The native can reach seven feet; shorter cultivars are available. Wet to average soil.

Northern Blazing Star (Liatris novae-angliae) A Northeastern native but rare in the wild. The more showy liatris spicata commonly sold in nurseries is native to the prairies of the Midwest. Butterflies, bees ,and songbirds love this distinctive, purple flower. The Kennebunk Plains is home to a spectacular population of this species along with a number of rare birds. Average to dry soil.

Cardinal Flower (Lobelia cardinalis) This intensely colored Maine native is a hummingbird favorite. A short-lived perennial (2–3 years), but it self-seeds readily in the right conditions. Wet soil.

Cutleaf Coneflower (Rudbeckia laciniata) Maine native. Tall (to 7’) stately coneflower with drooping rays. Bee and butterflies love this plant! Can be an aggressive spreader so be mindful of where it’s placed. Wet to average soil.

Blue Vervain (Verbena hastata) Airy, spire-like blooms on a tough plant. Attracts butterflies and provides special value to native bees. Host plant for the Common Buckeye butterfly. Wet to average soil.

Other Favorites (not pictured)

Narrowleaf Mountain Mint (Pycnanthemum tenuifolium) Tolerates dry conditions once established. Loved by bees and other pollinators. A good meadow plant with a wonderful minty fragrance. Can spread aggressively but is easily controlled. Dry to average soil.

Steeplebush* (Spiraea tomentosa) Native to Maine but not commonly seen in the wild. Average to wet soil.

New York Ironweed (Vernonia noveboracensis) A stately, sturdy, tall (up to 7 feet) late-blooming plant with attractive seedheads. Attracts bees, butterflies, and songbirds. Wet to average soil.

Common Yarrow* (Achillea millefolium) A tough, low-maintenance plant with flat-topped clusters of tiny white flowers. Aromatic, fern-like foliage adds texture to the garden. Spreads by rhizomes. Dry to average soil.

Woodland Sunflower* (Helianthus divaricatus) Bright yellow blooms provide late-season nectar for bees and butterflies. Spreads by rhizomes and is great for naturalized areas. Average to wet soil.

Flowering Raspberry* (Rubus odoratus) Large, rose-like purple flowers attract bees and other pollinators. Forms colonies and works well in informal plantings. Creates a thick, low border if allowed to spread. Average soil.

Rough Goldenrod* (Solidago rugosa) A robust goldenrod with arching stems and dense clusters of bright yellow flowers. Tolerates a range of conditions and works well in meadows and borders. Average to dry soil.

Resources

1. Plant Finder by Native Plant Trust/GoBotany has a terrific search tool with extensive filters to assist in finding a plant. Those filters include: Cultivation Status, Exposure, Soil Moisture, Ecoregion, Ornamental Interest, Wildlife Attractiveness, Tolerance, Additional Attributes, Landscape Use Foliage/Fruit and Growth Habit.

2. Dr. Annie White Research on whether Native Cultivars are as valuable to pollinators as native species.

Book Review: Glorious Shade: Dazzling plants, design ideas, and proven techniques for your shady garden Jenny Rose Carey (Timber Press, 2017 348 pp)

By Naomi Jacobs, Penobscot County Master Gardener Volunteer

Those of us who garden in the shade know it can be both a blessing and a curse. Though a shade garden can be a cool oasis on a hot day, and a feast for the eyes with its many textures and intensities of green, plants may struggle to flourish given the dry, poor soil under shallow-rooted trees as well as the low light. Beyond the reliable standbys like hostas and ferns, I tried and failed over many years to establish other perennials and groundcovers that were supposedly suitable for shade, before I began to achieve the results I wanted.

I wish I’d had a copy of Jenny Rose Carey’s Glorious Shade to guide my experiments! I haven’t encountered another book that contains such precise, detailed advice on how to design, plant and tend a beautiful shade garden. The style is chatty and accessible, the information fine-grained, and the cultural recommendations clearly come from a person who has spent decades with her hands in the dirt.

The author, originally from England, has been developing her 4.5-acre Northview Gardens in Pennsylvania since 1997. She is the former senior director at the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society’s Meadowbrook Farm in Jenkintown and former director of the Ambler Arboretum at Temple University. For more information about Carey and photos of her gardens, go to Northview Gardens.

I hope this overview of her book will give you a sense of how helpful it can be.

Shades of Shade, Observing Shifting Patterns in Your Garden

This opening chapter includes beautifully clear definitions of different types of shade (full, part, edge, dappled, bright, morning & afternoon) and explanations of how to design for sites where light conditions can vary from full shade to hot afternoon sun in the course of the day. Carey has many helpful observations on the dynamic nature of shade, especially shade cast by moving branches, as well as factors other than trees that affect the type of shade. For instance, shade will be brighter near surfaces that bounce light around, like bodies of water or white-painted walls. Also, shade levels can change throughout the year as the angle of the sun changes and deciduous trees lose their leaves. A savvy gardener can deepen shade by adding structures like fences and pergolas or can brighten shade through techniques like selectively thinning tree limbs, incorporating trees with light-colored trunks like birches, or painting a fence a lighter color.

The Gardener’s Calendar: Seasonal Changes in the Shade Garden

Here Carey explores the “cyclical rhythm” of shade gardens, with certain types of plants taking on more importance at certain times of year. It’s important to design one’s garden with a recognition that a given area might be sunny in April, come into dappled shade in June, and then be fully shadowed by a neighboring building in September as the angle of the sun declines. For each season, Carey provides lists of recommended plants and of tasks to be done.

Down and Dirty: The Intertwined, Underground World of Soil and Roots

Besides offering a basic understanding of soil structure and root functions, this chapter covers practical topics such as how to build soil in ways that mimic the natural processes that produce woodland soils; how to avoid damaging tree roots and compacting soil when planting and mulching around trees; how to encourage mycorrhizal activity in the soil; how to deal with poor soil near a foundation; and how to take advantage of microclimates.

Planting for Success: Techniques and Management

Here you’ll find a wealth of concrete, practical tips for planting and maintenance. For example, Carey suggests that new herbaceous groundcovers shouldn’t be planted right next to a tree, where they are unlikely to take hold and where the digging might harm the tree roots. Rather, one should leave some open space. Eventually the new plants will expand into that space and sometimes even grow right up over the tree roots. In a similar vein, she advises choosing new plants with small root balls because holes for large plants may endanger tree roots and younger plants are more vigorous. If smaller plants aren’t available at the nursery, you can divide a big one to get the size you want. Gardening around trees takes patience, but many lovely plants such as columbines, Epimedium, and bigroot geranium can coexist happily with trees if given time to settle in. Carey also discusses special considerations about mulch and fertilizer in the shade garden with the general principle of “Less is more.”

Designing in the Shadows: Bright Ideas for Shady Spaces

Carey is a talented and sensitive photographer, whether capturing a large garden landscape or an extreme close-up of a Sanguinaria (bloodroot) about to unfold the leaves clasping its stem. This chapter features inspiring photos of a variety of shade gardens, including woodland gardens, moss gardens, courtyard gardens, water gardens, Japanese gardens, rock gardens, container gardens, rain gardens, stumperies, and orchard gardens. Carey also offers advice on the use of paths, raised beds, sitting areas, water features, and areas for children.

The Plant Palette: Choosing Plants for Your Shade Garden

The second half of the book is a richly illustrated encyclopedia of roughly 200 annuals, perennials, vines, shrubs, and trees suited to shade. Though Carey herself gardens in the “warm side” of Zone 6, the great majority of her featured plants are hardy to Zones 4 and 5. Each entry includes a photo, information on the type of shade and soil the plant prefers, ideas on companion plants, and seasons of peak performance. This information is specific even to different species within a genus, such as that Geranium macrorrhizum (bigroot geranium) is recommended for “bright to full shade” while Geranium sanguineum (bloody cranesbill) is best suited to “edge or part shade.”

So often these days when we look for gardening information online, algorithms serve up vague, generic advice apparently generated by AI, like “give your plants enough light” and “water your plants before they are too dry.” By contrast, a book like Carey’s is the product of a real human being who has devoted her life to learning about a wide range of plants and helping them to flourish. Her deep knowledge of both horticulture and landscape design makes Glorious Shade a treasure trove of useful information, a pleasure to look at, and an inspiration to read.

Profiles in Urban Agriculture: Growing an Urban Orchard

By Carrick Gambell (he/him), Urban Agriculture Professional UMaine Cooperative Extension and Natural Resources Conservation Service

“I can’t believe I never knew this place existed,” a participant mentioned during a workshop in June at Mt. Joy Orchard. This reaction is common, even for Portland residents. The Orchard is perched inauspiciously on a steep hillside in Portland’s East End. Hundreds of drivers pass by every day, on their way to I-295 or to visit one of the neighboring restaurants and breweries. Once established, urban agriculture projects like this can seamlessly fit into the cityscape. But there is nothing inevitable about Mt Joy. This orchard is the product of a visionary and collaborative community, and passionate group of volunteers. Today, this verdant hillside provides peace and nourishment within Maine’s largest city.

A decade ago, this park was maintained as a lawn. The space was underused, and the parks department was tired of constantly mowing. The city arborist thought the site would be suitable for an orchard, and solicited community support to bring the project to life. The Resilience Hub, a local group with permaculture expertise, volunteered for the task. They intended to start small, but soon realized the enormous potential for the space. The initial vision for a small orchard blossomed into a hillside covered with trees. Since 2015, the orchard has expanded every year, and now hosts over 100 different fruiting trees, representing 20 different species. Perhaps most remarkable about this project is the degree of community oversight. Since the City delegated this project, all planning, planting, and maintenance has been done by volunteers. A core committee organizes bi-monthly work days during the growing season, and hosts popular community events such as a cider pressing in the fall and a “wassail” in the winter to prune and celebrate the trees. Aaron Parker, one of the original organizers, remarked that the project has felt consistently rewarding and manageable due to the passion and joy of the volunteer community.

When fruits are ripe, anyone interested is encouraged to harvest. There is no cost, and no one monitors the orchard. Community members must treat this place as a commons, picking what they need, and leaving enough for their neighbors. While trees in September are laden with apples, visitors can also expect to find mulberries, cherries, pears, peaches, paw paws, and low-bush blueberries. Some visitors just sit and cool off in the shade of the mighty oaks along the orchard edge. And humans are not the only happy inhabitants. Bees and birds hum and flit through the flowering trees and nearby meadow, buzzing loudly enough to compete with roaring engines from the nearby highway. DeKay’s Brownsnake, a species of Special Concern in Maine, have been spotted throughout the orchard.

Urban agriculture projects exist throughout Maine, from community gardens to vertical farms. These projects often face steep hurdles, from development threats to unaffordable land. Mt Joy Orchard represents the profound impact that can occur when a city creatively reimagines public space, and a community steps in to care for that space. To visit the orchard or get involved, visit their website.

Backyard Bird of the Month: Red-bellied Woodpecker

By Stacia Brezinski, Maine Audubon Field Naturalist

If you don’t know any better, you might mistake the Red-bellied Woodpecker’s call for that of a frog, or perhaps a clown lost in the woods. This isn’t a bird you would have heard often if you grew up in Maine, but now their loud, rolling “kwurr” can be heard commonly in the southern part of the state. Their range has been rapidly expanding northward since the 1950s as a result of climate change, tree plantings, and bird feeders. Red-bellied Woodpeckers are the only bird in the genus Melanerpes found regularly in Maine, which is why their calls may sound so unfamiliar.

This is a suet-loving species, and they seem comfortable in suburban and even urban habitats. Their diet is varied: everything from arthropods and seeds to nuts, fruit, sap, eggs, nestlings, and small vertebrates like lizards and fish. They have a chisel-shaped bill that can just as easily glean an insect from a leaf as it can hammer open an acorn. They don’t drill into bark as often as other woodpecker species, but when they do, their long, barbed tongues extract larvae and other foods from holes and crevices.

Look for the thin black and white “zebra stripe” markings on their backs, cream-colored undersides, and bright crimson heads. Males have red mullets framing their face and extending down the napes of their necks. Females have red only on the nape. But what about the red belly? Red-bellied Woodpeckers have a small, hard-to-see patch of pale red on their undersides, between their legs. They were given their English name by the same 18th century naturalist who named the Red-headed Woodpecker at around the same time, so it seems a more apt name was already taken! Their perplexing name, varied feeding behavior, and silly-sounding call make Red-bellied Woodpeckers a charismatic recent addition to Maine fauna.

Maine Weather and Climate Overview

Sean Birkel, Assistant Extension Professor, Maine State Climatologist, Climate Change Institute, Cooperative Extension University of Maine

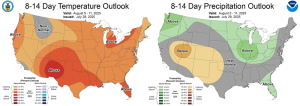

Weather station observations for July 1–28 show that temperature has been above normal (top 1/3 rank) statewide. Much of July has also been humid, contributing to morning low temperatures generally staying in the 60s Fahrenheit across the southern interior and coastal climate divisions. July precipitation has been much below normal for most of the state, with the exception of northern Aroostook County where rainfall from cyclonic storms has contributed to near normal conditions. As shown on the Northeast DEWS Dashboard, recent precipitation deficits have led to below or much-below normal 7-day streamflows across several monitoring sites. Most groundwater monitors show normal range, but some sites in the southwest and mid-coast show below normal. Drying topsoils are starting to impact lawns and gardens, increasing the need for watering.

In the latest 7-day forecast (afternoon of July 29), the U.S. and European global models show a large wave trough developing that will draw cool, dry air from Hudson Bay and western Canada across Maine and the Northeast region for the first couple days in August. The remainder of the first week continues to be influenced by high pressure without much precipitation signal, aside from minor amounts associated with afternoon convection. NOAA’s probabilistic climate outlook for August and the three-month outlook for August-October show above normal temperature and equal chances of above or below normal precipitation across Maine. NOAA’s 2025 North Atlantic hurricane season outlook suggests 60% chance above normal, 30% near normal, and 10% chance below normal activity (see also this summary graphic). Most tropical storm activity occurs between mid-August and mid-October, with the season peaking mid-September. As always, visit weather.gov for the latest weather forecast for your area. Additional climate and weather data and information is available on the Maine Climate Office. website.

| Product | Temperature | Precipitation |

|---|---|---|

| Days 8-14, Aug 5-11 (issued July 28) | Above Normal | Near Normal |

| Monthly, Aug (issued July 17) | Above Normal | Equal Chances |

| Seasonal, Aug-Sep-Oct (issued July 17) | Above Normal | Equal Chances |

Do you appreciate the work we are doing?

Consider making a contribution to the Maine Master Gardener Development Fund. Your dollars will support and expand Master Gardener Volunteer community outreach across Maine.

Your feedback is important to us!

We appreciate your feedback and ideas for future Maine Home Garden News topics. We look forward to sharing new information and inspiration in future issues.

Subscribe to Maine Home Garden News

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications, click on the Subscribe button below.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

For more information or questions, contact Kate Garland at katherine.garland@maine.edu or 1.800.287.1485 (in Maine).

Visit our Archives to see past issues.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around Maine. The following staff and volunteer team take great care editing content, designing the web and email platforms, maintaining email lists, and getting hard copies mailed to those who don’t have access to the internet: Abby Zelz*, Annika Schmidt*, Barbara Harrity*, Kate Garland, Mary Michaud, Michelle Snowden, Naomi Jacobs*, Phoebe Call*, and Wendy Robertson.

*Master Gardener Volunteers

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2023

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.