Maine Home Garden News – October

In This Issue:

-

- October Is the Month to . . .

- Growing Together in the Orono Community Giving Garden

- Creating a Native Wildflower Meadow

- Digging, Dividing and Replanting Peonies

- Fall Learning Opportunities for Gardeners and Professionals

- Backyard Bird of the Month: American Redstart

- Maine Weather and Climate Overview

October Is the Month to . . .

By Kate Garland, Horticulturist, UMaine Cooperative Extension

This slightly adapted article originally appeared in our October 2021 issue.

Dig dahlias. When cold temperatures kill the top growth on your dahlias, mark your calendars two weeks out for digging day. This time left in the ground after the frost allows the tubers to continue to develop and cure for better storage results. If you’re reading this and the frost hasn’t hit, remove any weak or poor performing plants to avoid taking up precious storage space with less desirable plant material.

Harvest sweet potatoes. Sweet potatoes are a great crop for Maine gardens and will continue to develop right up until frost kills the vines. Be gentle as you harvest and take the time to cure them before storing to ensure a longer shelf life.

Monitor and prevent jumping worms from spreading between sites. Even if you don’t suspect they’re on your property, equip yourself with knowledge to help avoid becoming one of the many who have experienced the ecological damage these worms can cause to both managed and natural landscapes.

Prepare a hole for your live Christmas tree. Live Christmas trees require patience and planning in order to ensure greater success when transitioning them to their final home in your landscape. They should be planted in the ground as soon as you are done enjoying them indoors. As you would expect, it’s much easier to get a planting hole ready now compared to the conditions you’ll encounter after the holiday season.

Plant garlic. Garlic is an easy crop to love for many reasons. It requires very little maintenance, has relatively few pests and a long shelf-life, is fun to plant as the season comes to a close, and is equally fun to enjoy in savory dishes all winter long. Wait until the weather cools before planting the cloves. Our bulletin has some very helpful planting instructions and videos.

Leave the leaves. We’ve said it before and we’ll say it again. It bears repeating that this practice will have a great impact on the survival of countless insects that rely on leaf litter for overwintering protection. Countless species of moths, butterflies and bees rely on this natural cover to complete their life cycle.

Water in newly planted perennials. Fall is a great time to plant, but providing ample water going into the colder months is key to overwintering success.

Take garden measurements. Winter is an important planning time and accurate measurements are incredibly helpful to have on hand when mapping out your garden for the season ahead.

Store leftover seeds. Don’t toss out those extra seeds! Many seeds stay viable for several years if stored in a cool, dry location. The back of your refrigerator in a watertight jar is a perfect spot for your seed stash. With that said, don’t bother storing onion family seeds. Their viability drops dramatically after the first year.

Growing Together in the Orono Community Giving Garden

By Rita Buddemeyer, Penobscot County Master Gardener Volunteer (formerly of Hancock County)

Plants flourish as do gardeners and their community as was intended when the expanse beside the Orono Library and Community Center became the town garden in 2004. John Jemison, soil specialist at University of Maine Cooperative Extension, opened the space with a vision of promoting health on a sustainable foundation. Today the now 2400 square foot garden boasts soil so rich and robustly productive it will amaze any gardener. Equally significant, the garden is wrapped in an atmosphere that radiates peacefulness even as it hums with activity.

From the onset, the aura was as purposefully cultivated as were the gardens; both grew well, and they continue to do so. Diane Smitherman has volunteered since 2010 and upon John’s retirement took over management of the garden. At the heart and from the heart the guiding principle is, “People Matter.” Thus, gardening is an engaging learning experience as much as it is an application of science. Volunteer Katy DaSilva beams when speaking of the enriching experience being part of and simultaneously giving back to the community. A core group of about 6 volunteers, and at times as many as a dozen others, are grateful to do what they love to do. Then there are those who stop in for the fresh free produce and end up in the garden. In addition there are passers by who delight in the surprise of being in the midst of such pleasant people and plants.

As for the vegetable production, which benefits those in nearby housing projects and is distributed directly from the garden and through the nearby Orono Food Cupboard, that’s quite a weighty matter. No wonder, given that harvests beginning in May include asparagus, parsnips, green onions, rhubarb, and greens. The bounty continues through November when collards, greens, turnips, and Brussels sprouts are enjoyed. One would have to see to believe sweet onions as large as softballs, garlic heads as big as one’s fist, and tasty vegetable varieties of every sort covering the picnic table which gardeners refill as quickly as consumers stop in to collect produce. St. Fiacre, the patron saint of community gardens, smiles while watching the wonder of it all.

Due at least in part to its broad network of connections, this Master Gardener Volunteer site is certain to continue its significant work. It is on town land, cared for by Orono Parks & Recreation, and promoted by the town. Financial and material support is also offered by Food AND Medicine as well as the Orono Health Association and other local donors such as the Church of Universal Fellowship. The children’s department of the library offers gardening experiences and special events in the garden as they plant seeds of health and happiness on a sustainable foundation. The magic lives on due to the wisdom and industry of volunteers.

Creating a Native Wildflower Meadow

By Tammy Libby, UMaine Extension Androscoggin County Master Gardener Volunteer

How to establish a meadow has been a topic of growing interest.

Miriam Webster defines a meadow as land that is covered or mostly covered with grass. Sounds pretty easy right? Just let your lawn grow and you will have a meadow. Unfortunately, it is not that easy. Often lawns in Maine are created with grasses not native to our region (the exception being red fescue). Lawns are typically designed for aesthetics such as color or growth habits and to withstand repeated foot traffic.

A meadow is more than grass, it‘s an entire ecosystem. Yes, it contains grasses, but also native grasses and wildflowers that support a diverse group of insects, reptiles, birds and animals. Meadows provide food, shelter, filter and absorb water, help prevent soil erosion and help with carbon sequestration.

Can you create a meadow? Yes. First consider how much time you have to devote to the project and do some research with reliable sources like the ones listed below.

The University of New Hampshire (UNH) has conducted extensive research and field testing on creating meadows. Their fact sheet Planting for Pollinators: Establishing a Wildflower Meadow from Seed by Cathy Neal, Extension Professor and Specialist, provides valuable insights from this work. UNH recommends thinking of establishing a meadow as a three-year project and considering several key factors before getting started.

- Determining the size and scope of the project. UNH research supports 400 square feet as a minimal size for a meadow (20 feet x 20 feet). What is your starting point: existing lawn, bare ground from new construction, a recently cut wooded area? Each requires a different approach to convert it into a meadow. Now is also a good time to check to see if your area has any local or state landscape ordinances.

- Assessing and preparing the site. What are the current conditions of the area and how do they change throughout the year? Is the site particularly wet, dry, sunny, shaded, or weedy? Are there existing invasive plants you will need to eliminate? What is the soil composition: sandy, clay, high or low pH? Unlike a perennial garden, meadow wildflowers can thrive in poor soil conditions so no soil amendments may be needed at all, thus saving time and money. Assessing and preparing the site is the most important and time-consuming step to achieve success establishing a meadow.

- Choosing what to plant and when. Research which native plants are best suited for the site conditions and your overall aesthetic goals. Native Plant Trust’s Plant Finder Website gives users the ability to search for native plants by name or filter by traits like flower color, site conditions and region to find species suited to their garden. If you’ve already fallen in love with a plant and are wondering if it’s native, Native Plant Trust’s Go Botany website is a good resource to determine native status.

Are you starting the meadow from seed, nursery plants or a combination of the two? In Maine, late fall is typically the best time to sow seeds that need a period of cold to germinate, while nursery plants can be planted anytime from early spring to mid fall. Take care in your planning and timing so you do not disturb one type while planting the other. If doing a combination, consider planting in the spring and sowing in between the new plants in the fall.

NOTE: If using a commercial wildflower seed mix, carefully read what it contains. Not all the seeds may be of plants native to or suited for your site. Creating your own blend from smaller packets may lead to better results. - Setting expectations. Remember meadow creation is a three-year process.

-

- Year one is all about planning, preparation, and elimination of existing unwanted vegetation, weeds or seeds.

- Year two – Allow small seedlings to grow, continue to carefully remove weeds and monitor for invasives that can crowd out your newly emerging seedlings. Diligently watch for invasive species as they too will thrive in a newly prepared site.

- Year three – Surviving plants will be stronger and larger. Weeds should be fewer and more easily crowded out by the larger, more established, wildflowers and grasses. Fill in any bare spots missed during planting or where plants may have failed.

- Year four and beyond is the time to admire your hard work and watch it evolve. Continue to monitor the area to prevent weeds or invasives from taking over. Some research says to mow the meadow once a year after wildflowers have dropped their seeds while others say to just leave it alone. I say enjoy it and do what works best for your site and the new residents it supports.

Meadows are an important part of our landscape. Unfortunately, meadows are declining due to a variety of reasons such as urban development, climate change and habitat loss to invasive species. However, meadows can be created. If one is willing to invest the time necessary for proper preparation, a meadow can be enjoyed for years with minimal work. This is a good time to weigh the costs of mowing, watering, and maintaining a large lawn and decide whether now is the right moment to plan for creating a meadow in your landscape.

Resources:

UNH Cooperative Extension – Establishing a Wildflower Meadow from Seed

UNH Webinar on Planting for Pollinator Habitat

University of Maine Cooperative Extension Pollinator Friendly Gardening

Wild Seed Project – Monarchs and Milkweed

Digging, Dividing and Replanting Peonies

By Nita Stormann, President of Peony Society of Maine, Brewer Garden and Bird Club Secretary and Penobscot County Master Gardener Volunteer

Once a peony has been planted in a properly prepared and preplanned location, you may never have to move it again. It is often said they will outlive the original planter as they have been known to live 50 – 100 years. Based on my past experiences I have listed four reasons why you may want to, or have to, move these easy to care for plants.

- Propagation: for sharing with friends, family, or wanting more of the same plant; to increase your personal stock.

- Relocation: from a now too shady location to an area with more sunlight as the growth progression has slowed down or fewer blooms are appearing; you may want to renovate the garden space; the plant is now too close to the mature tree line and competing with other roots for food and space.

- Create space for growth of the plant: over the years the tubers have become a tangled knot or the tubers need more space to extend outward in a clear path that is not competing with other plants or roots.

- Over crowdedness: above the soil you need adequate space between mature plants. It is recommended that plants be at least three feet apart to allow air flow around each plant thus preventing disease. Below the ground surface some of my tubers have grown three feet beyond the umbrella of the plant. These tubers may also become matted to others causing a rot to eventually occur. Old clumps have big but fewer ‘eyes’ (small buds at the top of the root system indicating where top growth will develop) compared to younger two- to three-year-old clumps with many but smaller ‘eyes.’ While smaller and younger clumps are easier to dig up and divide compared to a plant over 10 years old, try not to divide clumps less than every three to five years.

The following are recommended steps for dividing and replanting peonies.

Step 1 – Prepare the new area

Before you start to dig up a peony you need to prepare the new planting area. The space should be larger and deeper than the new tuber. As tubers develop they differ in shape and size and you should adjust your hole accordingly. Never replant in the same hole you dug from unless you put in new soil and amendments for rejuvenating. This is a way of controlling bacteria and disease and giving nutrients to the soil and plant. Also make sure all old tubers are removed from the old site. Adventitious roots may be capable of producing new buds and stems from blind roots. Next fill the hole with water to test for adequate drainage. Add and mix top soil, dried manure and humus (composted/organic material) together. Add two handfuls of bone meal per hole (phosphate for root growth).

Step 2 – Dig the peony clump

When digging up your peony clump and the ground is dry, water the area deeply to loosen the soil. Using a pitch fork or a shovel start about 12 inches from the outer base diameter. Place your tool to dig down and then try to lift up or loosen the clump’s roots. Do this all around the entire plant several times, as the goal is to remove the entire clump and root system. The older the plant the harder this will be. You will hear cracking sounds as you may break off tubers and roots while separating the plant from the soil. The tuber, unless diseased, will heal nicely when broken. This is the hardest process and may take a little time to accomplish. Lifting the soil covered clump out of the hole may be a two person job.

If one wants to give a friend a start from a clump without digging the entire clump up and setting back the transplanting, soil can carefully be removed from one side of the crown, with a water hose and fingers, to see where the ‘eyes’ and tubers/roots are located. Then carefully cut off a section with 3-5 ‘eyes’ using your spade or knife. Fill the hole with good soil and organic humus. Always remember to water afterwards.

Step 3 – Clean and divide the clump

Once the clump is out of the ground you need to gently wash off the soil to avoid breaking off the new ‘eyes.’ Place the clump on a firm surface and inspect it for ways to separate the tubers into sections. The tubers will grow new feeder roots once planted and will quickly form a new barklike covering, so don’t be timid about decreasing the length of the tubers or removing all diseased parts and rot. Old peony tubers have a lot of rot. You will need a clean large knife. To cut apart the tubers some gardeners use a small hand saw and clippers. Separate the tubers without damaging the ‘eyes’ leaving 3-5 ‘eyes’ on each tuber.

The tuber will not survive without ‘eyes.’ At least three ‘eyes’ will ensure stem growth next season and possibly a bloom the first year. I try to start out with five ‘eyes.’ You should give the new peony at least two seasons before worrying if you did something wrong (unless there are obvious other problems), as it needs time to mature.

Step 4 – Plant the divided tubers

You have accomplished digging and dividing as described above with only planting left. Your tuber is clean and your hole is prepared. Plant your tuber with the eyes facing up. The tuber may naturally go straight down or lay horizontally. If you are planting a recently dug peony and have cut the stems back to 1-2 inches you will see the soil demarcation. Use this as a marker with the stems protruding 1-2 inches above the soil and the eyes 1½ – 2 inches under the soil. Adjust your added amendments in the hole to allow the ‘eyes’ to be covered with not more than 2 inches of soil.

If planted too deeply you may not have any blooms and slow growth will occur. Note that tree peonies’ ‘eyes’ need to be planted deeper at 2-3 inches. Water the area to settle the soil and allow the amendments to get close to the tuber, but don’t saturate it.

You will want to plant your peony before a hard frost and the ground freezes. The tuber needs time to start replacing its damaged feeder roots. The latest I have planted is the end of November as our winters are becoming milder. The ground was much harder to work then.

Step 5 – Mulch, water wisely, avoid diseases and time your trimming for optimal health

For the first one to two winter seasons you should add some type of mulch. This will protect the plant from freezing rains and frost heaves. In the spring all mulch should be removed from around the base to prevent fungi and disease.

The first spring season make sure you water the plant from the bottom when dry without saturating it. Heat from the hot sun can damage fragile peony yearlings. Covering with a peony umbrella or offering some other form of shade during intense heat can help minimize damage during the establishment phase.

Unless you are collecting seeds from your peonies, you should deadhead your blooms leaving a well shaped bush for your garden foliage. Some peony leaves will turn a brown or tinted color that blends well with the fall season. DO NOT cut your peonies stems back at this time as nutrients are being stored below the surface for winter use and the ‘eyes’ are forming for next spring. You may be tempted to cut them back as powdery mildew may be present. When a hard frost has wilted the stems, you can trim them back leaving a 1-2 inch stem as a marker for next year. This usually occurs late September into October.

When you see your peonies all in bloom you realize all your hard work was worth it. Once you have done digging, dividing and planting several times it won’t seem so hard.

Fall Learning Opportunities for Gardeners and Professionals

By Rebecca Long, Coordinator of Horticulture Training Programs

Final Fall Webinars for Gardeners:

- Oct 7: Growing Native Plants from Seed – Learn to start your own native perennials.

- Oct 14: Beginner’s Guide to Composting – Build, maintain, and put your own compost pile to use.

New Webinar Series for Aspiring & Current Horticulture Professionals:

First Monday of each month

- Oct 6: Passion, Patience & Product: Starting a Native Plant Nursery – Practical tips for running a successful native plant nursery.

- Nov 3: Transitioning to Native Plants in the Landscape or Garden – Design with natives to meet your clients ecological and design objectives.

Last Chance to Enroll in Our 2025 In-Depth Horticulture Trainings:

These programs will not be offered in 2026 (and will resume in 2027), so now is the time to register!

- Maine Horticulture Apprentice Training – Flexible online learning plus hands-on apprenticeship experience for current or aspiring horticulture professionals.

- Maine Gardener Training – The same comprehensive training as the Master Gardener Volunteer program, without the volunteering requirement.

Backyard Bird of the Month: American Redstart

By Maine Audubon Field Naturalist Stacia Brezinski

Fall migration gives us a second chance to see trees full of normally secretive warblers, though some species have been fairly conspicuous all summer. American Redstarts are striking warblers that breed in Maine. Females and young birds have gray upperparts with a patch of yellow under each wing and yellow on the outer tail feathers. Males have black upperparts with blaze orange where the females have yellow, plus an extra bar of orange on the wing. Their long tails with flashes of color and acrobatic foraging style help birders pick them out in a crowd. Like most warblers, they’re primarily insectivorous, and are feasting right now as they migrate south to their winter homes in Central America, northern South America, and the Caribbean. They’ll spend the nonbreeding season in a variety of habitats, including mangrove forests, shade coffee plantations, and scrubby vegetation. As they flit around these forests and thickets, they’ll flash their bright, colorful wing and tail patches to startle insects, then pick them off with their thin, tweezer-like beaks. Look for them darting around in the leaves, catching insects in midair, and even hovering at the tips of branches. You can also listen for their nocturnal flight calls, starting a couple of hours after sunset. They make a short rising “tswee,” like an auditory check mark. Many birds, including most warblers, migrate at night to avoid predators and take advantage of cooler temperatures (imagine exercising for hours in a down jacket!). American Redstart migration peaks in late September and the first half of October.

Maine Weather and Climate Overview

By Sean Birkel, Assistant Extension Professor, Maine State Climatologist, Climate Change Institute, Cooperative Extension University of Maine

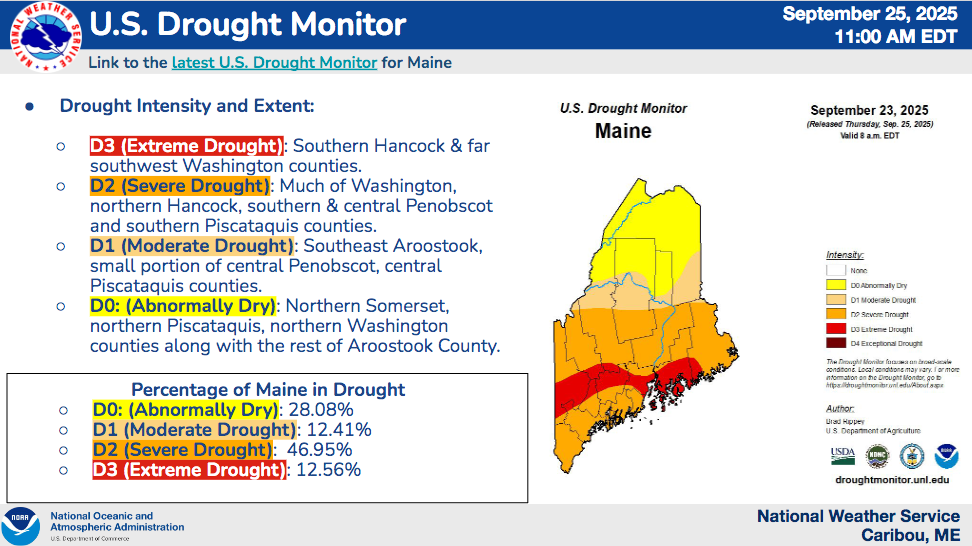

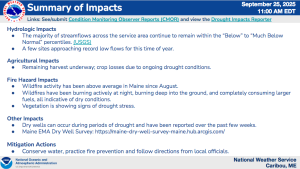

Drought continues in Maine despite some areas receiving beneficial rainfall in early September and again on the 25th–26th. As highlighted in a September 25 National Weather Service briefing, the U.S. Drought Monitor registers 28% of the state in D0 (abnormal dryness), 12% in D1 (moderate drought), 47% in D2 (severe drought), and 13% in D3 (extreme drought). The most recent rainfall, which was over 2 inches in some areas, moistened soils and reduced wildfire danger, but had little impact on groundwater due to the slow response times involved and large precipitation deficits accrued since June.

The latest NOAA forecast and outlook products show above normal temperature and near-normal or equal chance of above or below normal precipitation, suggesting limited opportunity for drought relief in October. See the U.S. Drought monitor map and impacts summary below provided by the National Weather Service. As always, your local forecast can be found at weather.gov.

Additional Drought Related Resources

Wildfire Danger Report – Maine Forest Service

Maine Dry Well Survey – Maine Drought Task Force

Maine Irrigation Guide 2024 (PDF) – Maine DACF

Farmers Drought Relief Fund – Maine DACF

USDA Service Centers

Northeast Drought Early Warning System Dashboard

Condition Monitoring Observer Reports (CMOR) – Drought-related conditions and impacts can be reported to this service provided by the National Drought Mitigation Center

Weekly Drought Update – Maine Climate Office

Recent Maine Statewide 2025 Temperature & Precipitation Rankings

- September: Statewide summaries are not yet available, but station data from Bangor, Caribou, and Portland show top 1/3 warmest and bottom 1/3 driest (Portland, Caribou) and near long-term average (Bangor).

- Jun–Jul–Aug: 16th warmest (top 1/3), 6th driest (bottom 1/10)

- August: 38th warmest (top 1/3), 9th driest (bottom 1/10)

- July: 13th warmest (top 1/3), 8th driest (bottom 1/10)

- June: 23rd warmest (top 1/3), 60th wettest (average)

Additional climate and weather data and information is available on the Maine Climate Office website.

Do you appreciate the work we are doing?

Consider making a contribution to the Maine Master Gardener Development Fund. Your dollars will support and expand Master Gardener Volunteer community outreach across Maine.

Your feedback is important to us!

We appreciate your feedback and ideas for future Maine Home Garden News topics. We look forward to sharing new information and inspiration in future issues.

Subscribe to Maine Home Garden News

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications, click on the Subscribe button below.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

For more information or questions, contact Kate Garland at katherine.garland@maine.edu or 1.800.287.1485 (in Maine).

Visit our Archives to see past issues.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around Maine. The following staff and volunteer team take great care editing content, designing the web and email platforms, maintaining email lists, and getting hard copies mailed to those who don’t have access to the internet: Abby Zelz*, Annika Schmidt*, Barbara Harrity*, Kate Garland, Mary Michaud, Michelle Snowden, Naomi Jacobs*, Phoebe Call*, and Wendy Robertson.

*Master Gardener Volunteers

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2023

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.