196-Beneficial Insect Series 2: Carabidae (Ground Beetles) on Maine Farms

Fact Sheet No. 196

Prepared by Allison Jones, Undergraduate Student; Sonja Birthisel, Graduate Research Assistant; Randa Jabbour, Assistant Professor of Agroecology at the University of Wyoming; and Frank Drummond, Professor of Insect Ecology; David Yarborough, Extension Blueberry Specialist, the University of Maine, Orono, ME, 04469. November 2013.

Introduction

Some of the dominant predators of insect pests in wild blueberry and other agricultural crops in Maine are spiders, ants, and ground beetles. Beetles of the family Carabidae, commonly known as the ground beetles, exhibit great diversity in size and behavior. They can be beneficial for both invertebrate pest control and for weed management.

Description

Most ground beetles in Maine have easily identifiable characteristics that distinguish them from other common beetles. These ¼ to 1½ inch long beetles are generally dark in color with a hard exterior structure (referred to as an exoskeleton). They are mostly nocturnal, but can often be seen scurrying across the surface of the soil. The following is a guide to common ground beetles in Maine, and to the benefits, they provide wild blueberry farmers and other agricultural producers in terms of natural pest control. In addition, we discuss important considerations for their conservation and enhancement.

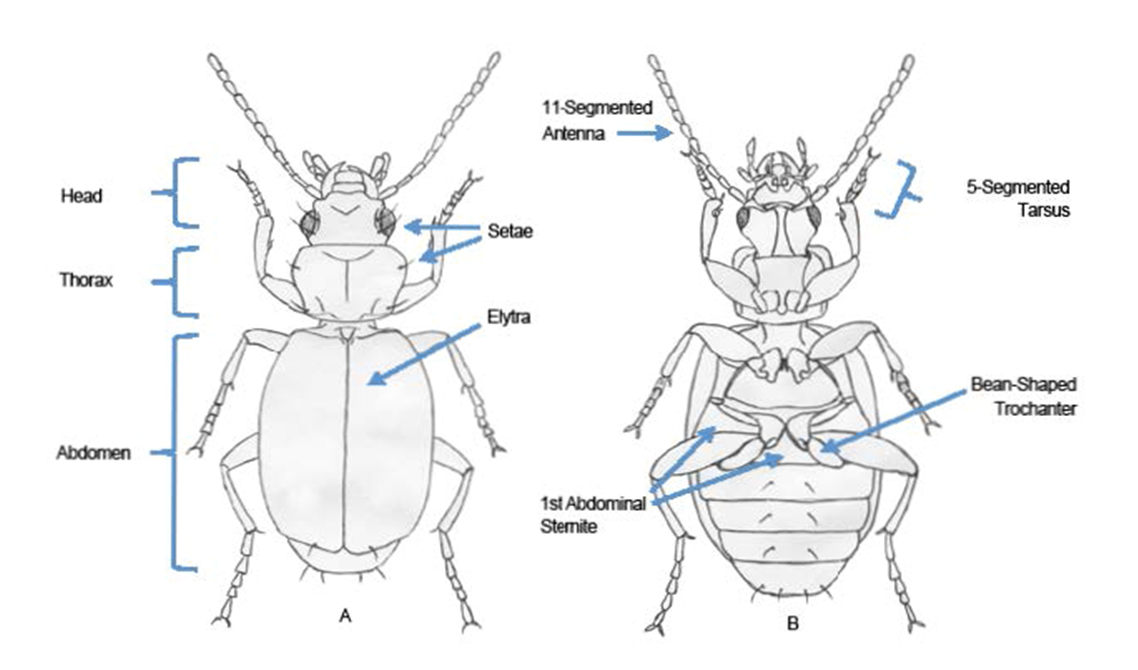

Ground beetles can be identified by the distinctive appearance of a large, jelly bean-shaped trochanter, see upper leg segment at the base of their hind legs. This lobed trochanter hides the entire first abdominal segment when looking at the ventral surface (from underneath). Beetles outside of this group do not have this feature. The one exception to this rule is the “false ground beetles” which have a similar body shape to ground beetles and large trochanters, but their coxa, which appears adjacent to the trochanter at the base of their hind legs are much larger.

Biology

The behaviors, preferred habitats, and diets of ground beetles vary. Adults are generally active from April-October. Most species produce a single new generation of adults (beetles) once a year. After mating, female adults lay eggs in the soil. The eggs develop into underground, six-legged larvae that are either predators of insects or seeds. When the larvae finish their development, they metamorphose into pupae and then shortly thereafter emerge from the soil as adults. This development can occur within one season, so this generation overwinters in the ground as adults but in some species, the new generation overwinters as larvae or pupae. There can be great diversity in life cycles, even among similar species.

In early spring, ground beetles are abundant in sheltered areas such as field margins. As crop fields provide increased vegetative cover and food availability throughout the summer, ground beetle activity increases. These beetles typically prefer vegetated habitats that may support high insect pest prey densities, provide a favorable microclimate, and afford protection from the ground beetles’ predators, which are larger ground beetles, mice, birds, and other large predators. Ground beetles are typically most active in late summer.

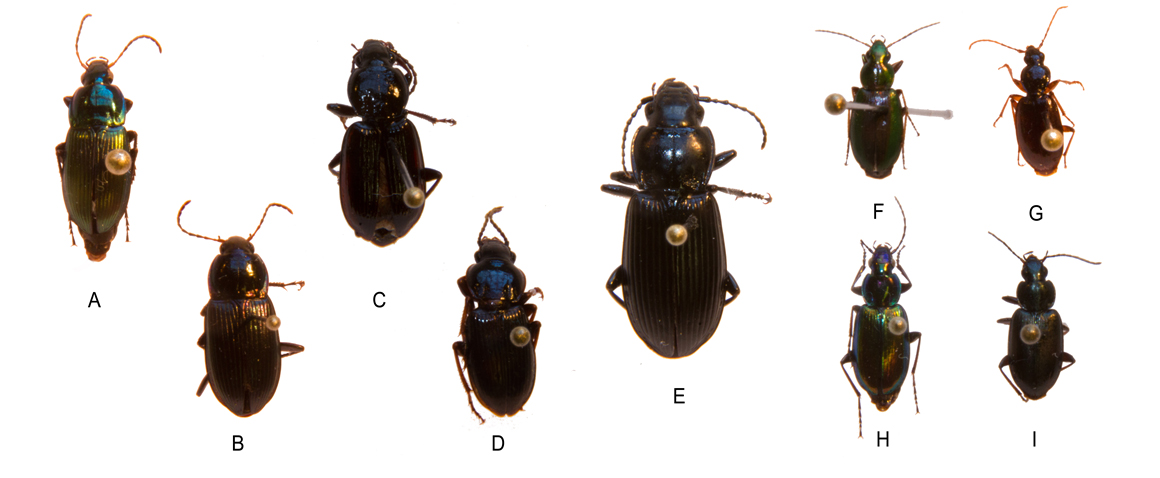

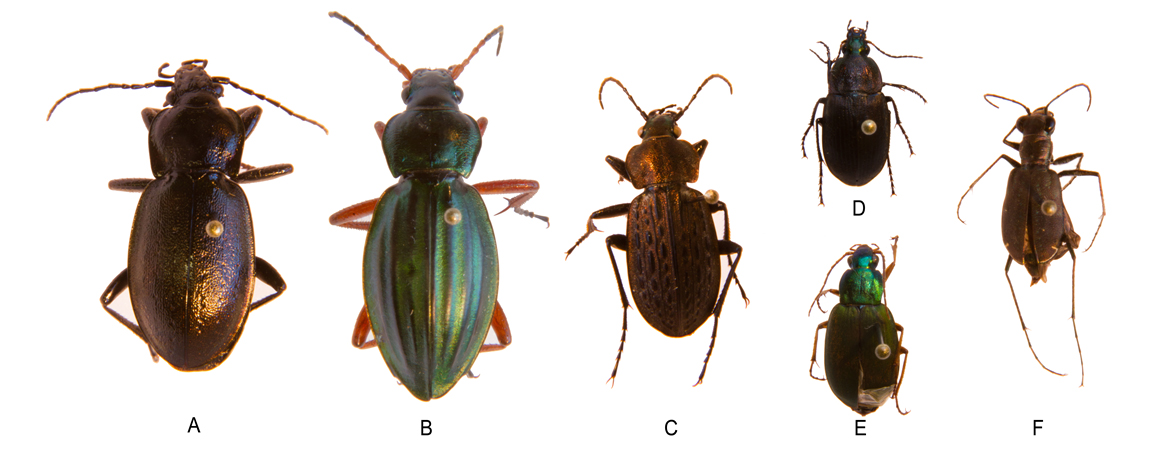

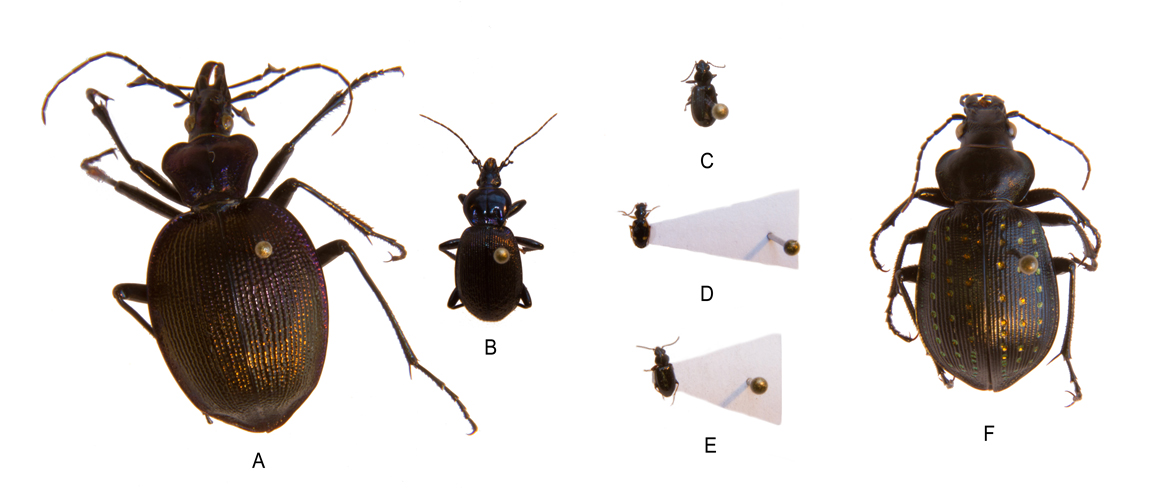

The most common ground beetles in Maine’s wild blueberry fields are the genera (groups of closely related species): Pterostichus (Figure 2, C-E), Calosoma (Figure 4, F), and Harpalus (Figure 1, A-D). In other Maine cropping systems, Harpalus is highly dominant, accounting for more than 75% of the ground beetles captured in several studies conducted on Maine vegetable and potato farms.

Even though most ground beetles are nocturnal, some species hunt by sight and are primarily day-active. These species are often iridescent, as iridescence reflects heat from sun, allowing greater heat tolerance. Examples of day-active carabids include Poecilus (Figure 2, A-B) and Carabus (Figure 3, A-C).

Ground beetles can be grouped as granivores, carnivores, or omnivores based on feeding preferences. Some species are broad generalists, while others are more specialized feeders. Ground beetle feeding preferences are generally not fixed; most carabids will opportunistically feed on whatever food is available.

They are considered a beneficial component of agricultural systems: many species consume insect pests and weed seeds. The cumulative effect of ground beetles on weeds and insect pests can be significant over time, given they can consume their own body weight in food daily. Ground beetles do not generally feed on plant matter other than seeds unless to supplement their diet due to the scarcity of other food sources. They are rarely considered direct crop pests.

Granivores: Amara (Figure 1, H) and Harpalus (Figure 1, A-D) species are considered to be the granivores (seed predators) of greatest importance on North American farms. Both larvae and adult beetles consume seeds. In total, 10 genera found in Maine include species that are granivores.

Omnivores: Pterostichine species (Figure 2, A-E), including members of the genera Pterostichus and Poecilus are the most diverse consumers, known to feed upon slugs, aphids, moth larvae such as blueberry spanworm, beetle larvae such as blueberry flea beetles, and weed seeds.

Carnivores: Calosoma calidum (Figure 4, F) feeds primarily on caterpillars such as blueberry spanworm. Other Calosoma species, along with Carabus nemoralis (Figure 3, A), have been utilized in gypsy moth control. Scaphinotus and Spaeroderus (Figure 4, A-B) have specialized mouthparts to dig snails from their shells.

| Table 1: Known Invertebrate Predation by Common Carabids | ||

| Carabid Species | Pests Consumed | |

| Bembidion quadramaticulatum (Figure 3, D) |

Eggs of armyworm, blueberry spanworm, blueberry flea beetle, cabbage fly, carrot fly, carrot weevil, cutworm, Japanese beetle, stalk borer | |

| Clivinia fossor (Figure 1, I) |

Bird cherry-oat aphids, carrot weevil, summer cabbage fly | |

| Harpalus rufipes (Figure 1, C) |

Bird cherry-oat aphid, black bean aphid, blueberry flea beetle, blueberry spanworm, cabbage aphid, cabbage fly, cabbage moth, Colorado potato beetle, English grain aphid, green peach aphid, rose-grain aphid, yellow wheat blossom midge | |

| Poecilus lucublandis (Figure 2, A-B) |

Blueberry flea beetle, blueberry spanworm, carrot weevil, Colorado potato beetle, cutworm, European corn borer, green cloverworm, kneelback slug, onion fly, stalk borer | |

| Pterostichus melanariu (Figure 2, E) |

Bird cherry-oat aphid, black bean aphid, blueberry flea beetle, blueberry spanworm, cabbage aphid, cabbage moth, carrot weevil, Colorado potato beetle, crane fly, English grain aphid, fruit fly, grey garden slug, leaf beetle, onion fly, rose grain aphid, summer cabbage fly, winter moth, yellow wheat blossom midge | |

Management

Promoting abundance and species diversity of ground beetles is possible through the use of management practices that provide suitable habitat and diversity of food sources. Management factors that can reduce ground beetles include disturbance events such as pesticide applications and burning. A positive means of enhancing ground beetles is the maintenance of non-crop ‘refuge’ habitats. These habitats are field edges or areas adjacent to or within fields that are not heavily managed, allowing ground beetles to have free access to insect pest or weed seed prey.

Insecticides applications can reduce carabids but the extent to which carabids are harmed varies based on several factors. In general, insecticides such as Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) or insect growth regulators such as Intrepid® (methoxyfenozide) used for blueberry spanworm control have little or no effect on ground beetles. The fungal pathogen Botanigard® (Beauveria bassiana), used to control blueberry flea beetle, has been tested against the ground beetle Harpalus rufipes, and has been found to cause little to no mortality. On the other end of the spectrum, a persistent insecticide such as Imidan® (phosmet) will likely kill your ground beetles.

Herbicides, too, can reduce carabid abundance and community assemblage through habitat modification, but research on the ground beetle community in wild blueberry fields has shown that almost twice as many ground beetles were found in high input fields compared to organic, low, and medium input fields. This suggests that factors other than pesticides might play a role in regulating ground beetle populations. Our hypothesis is that ground beetle predators such as ants, spiders, small mammals, and birds are lower in high input fields and thus allow ground beetles to occur at higher densities. In fact, in support of this hypothesis, we have found that ants are highest in organic fields.

Tillage in other agricultural systems is a direct cause of ground beetle mortality. Larger ground beetles, such as Carabus species (Figure 3, A-C), are particularly susceptible. In wild blueberries, pruning and especially burning may also indirectly affect beetles by removing crop residue from the soil surface, causing changes in soil temperature, moisture, and food availability.

During disturbance events such as pesticide application and pruning, the presence of non-crop ‘refuge’ habitat in the landscape can promote re-colonization of the crop area by ground beetles. Beetle banks are one means of conservation. These are popular in Europe and consist of approximately two yard-wide strips of land adjacent to crop fields that are sown with specific grasses and flowering perennials to provide overwintering and refuge habitat. Their benefit in Maine has not been studied, but grassy field margins and other non-crop habitats common in Maine agricultural landscapes may serve similar functions for ground beetle conservation.

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2013

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

The University of Maine is an EEO/AA employer, and does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender expression, national origin, citizenship status, age, disability, genetic information or veteran’s status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Director of Equal Opportunity, 101 Boudreau Hall, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5754, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).