Maine Home Garden News — October 2022

In This Issue:

- October Is the Month to . . .

- Facts About Leaf Color in Maine

- From School Garden to Outdoor Classroom-Part 1

- Game Review: Trellis (publisher: Breaking Games) by Teale Fristoe

- House Sparrow

October Is the Month to . . .

By Kate Garland, Horticulture Professional, UMaine Extension Penobscot County

Live in harmony with mushrooms. Moist conditions in the fall create the perfect environment for a variety of mushroom species to develop their “fruiting bodies,” or above-ground reproductive structures. If you find a bounty of mushrooms in your lawn or garden, there’s no need to be alarmed or take action in most cases. Always be mindful of inquisitive pets and children who may be tempted to take a bite of these ephemeral features.

Leave the leaves. Countless insects rely on leaf cover to complete their life cycles. Some species may overwinter as eggs or larvae attached to the leaves and stems of various plants. Some insects may rest tucked beneath a protective layer of leaves as adults. The more we can leave nature in place to serve as a habitat for insects, the more food will be available for birds and other animals over the chilly winter months. In addition, more pollinators will have a greater chance of survival.

Use row covers to extend the season. Some of the most successful gardeners have more of a marathon mindset instead of focusing on the “spring sprint.” While it’s great to get an early start, it can be just as rewarding and is often easier to simply protect crops at the end of the season. No fancy greenhouse is required! Wire hoops and a thick layer of row cover are all you need to keep cold-tolerant crops such as kale, swiss chard, broccoli, beets, turnip, spinach, and carrots on the menu for weeks to come.

Plant garlic. See Bulletin #2063, Growing Garlic in Maine. Garlic is tremendously fun and easy to grow. Aim to plant in late October in central Maine, a week or two earlier in northern Maine, and in early November for southern Maine gardens.

Plant garlic. See Bulletin #2063, Growing Garlic in Maine. Garlic is tremendously fun and easy to grow. Aim to plant in late October in central Maine, a week or two earlier in northern Maine, and in early November for southern Maine gardens.

Continue to take pictures. Even though your garden may be winding down and not looking its best, it’s still great to keep photographic records. This is especially true if you’ve been fighting a particular pest, disease, or weed that you haven’t had a chance to identify. Pictures can be incredibly useful in the diagnostic process and will help you make a game plan over the winter to address things moving forward. Plus, you won’t regret spending the minimal effort documenting where you left off for the season and you may be surprised how helpful those pictures are when it comes time to plan your 2023 garden.

Dig and store tender perennials such as dahlias, cannas, gladiolas, and begonia. Each species has its own set of ideal storage conditions. For more details on best practices, check out this helpful bulletin, Storing Tender “Bulbs” for Winter.

Continue hitting up the farmers’ markets! The best dishes come from the best ingredients and, if you can’t get it from your own garden, there’s no better place than the farmers’ market to find the freshest produce around. Maine farmers not only work hard to grow food for you, but many also generously donate tens of thousands of pounds of produce through the Maine Harvest for Hunger market gleaning program.

Facts About Leaf Color in Maine

UMaine Cooperative Extension Bulletin #7078

Originally adapted from Why Leaves Change Color, USDA Forest Service FS 12, February 1967. Revised by James Philp, Extension forestry specialist – wood products, July 2001.

Revised by Kathryn Hopkins, Extension Professor, August 2014.

Reviewed by Dr. Abby van den Berg, Research Assistant Professor in Plant Biology, University of Vermont Proctor Maple Research Center, August 2014.

Every fall, we delight in the beauty of the trees and shrubs, knowing that it is only a passing pleasure. Before long, the leaves will fall from the trees and become part of the rich carpet that covers the forest floor, providing nutrition for new forest growth. Many people suppose that frost causes color change, but it does not. Some of the leaves begin to change color before we have had any frost.

Every fall, we delight in the beauty of the trees and shrubs, knowing that it is only a passing pleasure. Before long, the leaves will fall from the trees and become part of the rich carpet that covers the forest floor, providing nutrition for new forest growth. Many people suppose that frost causes color change, but it does not. Some of the leaves begin to change color before we have had any frost.

A Chemical Process

During spring and summer leaves serve as food factories for trees’ growth. Photosynthesis, the food-making process, takes place in the numerous leaf cells that contain the green pigment, chlorophyll. Chlorophyll absorbs energy from the sun and uses it to change carbon dioxide and water to sugars and starches that are used for tree growth.

In addition to chlorophyll, leaves also contain yellow and orange pigments, such as xanthophyll and carotene. Carotene is the pigment that gives carrots their familiar color. For most of the year, the yellow and orange colors are hidden by the much greater amount of green pigment. In the fall, because of decreasing day length and temperature, the leaves stop producing chlorophyll. The remaining chlorophyll breaks down and the green color disappears making the yellow and orange colors visible. Some trees, such as silver maple, aspen, birch, and hickory, show only yellow colors.

At the same time, other chemical changes are taking place in the leaf. In some species, anthocyanins are formed, giving leaves a crimson red, purplish, or blue color. Anthocyanins give the reddish and purplish fall colors to dogwood and sumac leaves and give the sugar maple its brilliant orange, fiery red, or yellow colors. Oaks are mostly brownish, while beech turns a golden bronze. Mixtures of pigments in the leaves cause various colors during the fall season. Trees with red or scarlet leaves in autumn include red and sugar maple, flowering dogwood, sweetgum, black gum, red and scarlet oak, and sassafras.

At the same time, other chemical changes are taking place in the leaf. In some species, anthocyanins are formed, giving leaves a crimson red, purplish, or blue color. Anthocyanins give the reddish and purplish fall colors to dogwood and sumac leaves and give the sugar maple its brilliant orange, fiery red, or yellow colors. Oaks are mostly brownish, while beech turns a golden bronze. Mixtures of pigments in the leaves cause various colors during the fall season. Trees with red or scarlet leaves in autumn include red and sugar maple, flowering dogwood, sweetgum, black gum, red and scarlet oak, and sassafras.

It is believed that fall weather conditions may play a part in the formation of autumn colors. Warm sunny days, with nighttime temperatures below 45 degrees Fahrenheit but above freezing, raise the level of red coloration. Sugars, made in the leaves during the day, are used to produce the pigment, anthocyanin. The degree of color may vary between trees of the same species because of genetic differences. Colors can even vary on the same tree. For example, leaves directly exposed to the sun may turn red, while those on the shady side of the same tree may be yellow. The leaves of some trees may just die and turn brown, never showing any bright color.

The colors on the same tree may also vary from year to year, depending upon combinations of weather conditions. When there is a lot of warm, rainy weather in the fall, less red color can be expected. The small amount of sugar made in the limited sunlight is not sufficient to form the red pigments.

The timing of the color change on leaves depends on weather, latitude, elevation above sea level, and the local microclimate. Warm, but not excessively hot, temperatures and sufficient spring and summer rainfall will usually produce the best fall color. Many states have foliage maps and webcams to track foliage color changes as fall progresses. This makes it easier to plan a foliage-viewing trip for peak color season.

As the leaves change color, other things are happening to them. The leaf veins close off and stop carrying liquids. At the base of the leafstalk or petiole, where it is attached to the twig, a layer of special cells forms and gradually separates the leaf from the twig. This layer of special cells is called the abscission layer. It is the reason that the leaves fall from the tree. At the same time, scar tissue forms on the twig to seal the old pathway between the twig and the leaf. Leaf scars are so unique in appearance that they can often be used to identify trees after the leaves are gone.

Fall Colors for a Fortunate Few

Only a few regions of the world have showy fall displays. Eastern North America has large areas of forests with broad-leaved trees and favorable weather conditions for vivid fall colors. Some areas of western North America, especially in the mountains, also have bright coloration. Eastern Asia and southwestern Europe have colorful fall foliage, too.

Only a few regions of the world have showy fall displays. Eastern North America has large areas of forests with broad-leaved trees and favorable weather conditions for vivid fall colors. Some areas of western North America, especially in the mountains, also have bright coloration. Eastern Asia and southwestern Europe have colorful fall foliage, too.

Most broad-leaved trees in the north shed their leaves in the fall. Some of the oaks, and a few other species, may keep their dead brown leaves over winter until growth starts again in the spring. In the south, where the winters are milder, some broad-leaved trees are evergreen.

Most conifers — pine, spruce, fir, hemlock, cedar, etc. — are evergreen in both the north and the south. The leaves, which are needle-like or scale-like, remain green or greenish year-round. The individual leaves may stay on the tree for two or more years.

Fallen leaves help fertilize the forest soil. Leaves contain nutrients, particularly calcium and potassium, which the trees’ roots took up from the soil. Decaying leaves recycle the nutrients back into the top layers of the soil. The humus produced by the decaying leaves is also important for conserving water in the forest soil.

Leaf Projects

It is easy to copy leaves with crayons or colored pencils. Place a leaf, upside down, on a table or desk. Then put a sheet of writing paper (not thick drawing paper) on top of the leaf. Next, holding the paper and leaf so that they do not move, color the paper on top of the leaf. Use fast, slanting strokes. The shape and markings will be copied exactly, with the veins and leaf border showing as darker lines. After coloring over the leaf, you can cut out the paper leaf with scissors. Green leaves can be copied at any time in this way.

You can use a color photocopier to make exact copies of colored leaves. Or, you can use a black and white photocopier, at a lighter setting, to make pictures to color with crayons. Use fresh leaves that have not begun to wilt or wrinkle. Cutouts of the paper leaves can be used in a wide variety of art projects.

Leaf prints can also be made with an inked stamp pad. Press the leaf’s lower surface against the stamp pad with a piece of paper on top to keep your fingers clean. Then place the leaf, inked side down, on a sheet of white paper, with another sheet of paper on top. Hold the leaf firmly and rub it hard over it. When the upper sheet of paper and the leaf are removed, a printed copy of the leaf will remain. A scrapbook of leaf prints, with names of the trees, is an interesting project for youngsters.

This work is supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, RREA project 228285.

From School Garden to Outdoor Classroom-Part 1

By Christa Little-Siebold, Hancock County Master Gardener Volunteer

Imagine a school whose entire campus is conceived as an Outdoor Classroom: a hands-on learning space to nourish the souls and intellects of all. The concept requires thinking outside the box, taking the school garden beyond a few raised beds and to the next level where the richness of the whole campus can become an essential resource for education.

Imagine a school whose entire campus is conceived as an Outdoor Classroom: a hands-on learning space to nourish the souls and intellects of all. The concept requires thinking outside the box, taking the school garden beyond a few raised beds and to the next level where the richness of the whole campus can become an essential resource for education.

Whether you are starting, invigorating, or revitalizing a school garden, I encourage you to tackle each small project within a larger re-imagined vision of the campus as a whole. Let me take you on a visualization tour.

We start in April with two raised beds shining with radishes, the end product of a kindergarten math lesson. A sea of daffodils skirt along the edge of the forest strip outside the playground, each flower representing a staff member or a student. In May, the bus circle loop is radiant with red tulips. The 7th graders have already reported the data on bloom times in their Tulip Test Garden as a citizen’s science project.

We start in April with two raised beds shining with radishes, the end product of a kindergarten math lesson. A sea of daffodils skirt along the edge of the forest strip outside the playground, each flower representing a staff member or a student. In May, the bus circle loop is radiant with red tulips. The 7th graders have already reported the data on bloom times in their Tulip Test Garden as a citizen’s science project.

Imagine now that the strips of dirt around the parking lot have become a biology classroom. In June, 4th graders with magnifying glasses count and identify the insects feeding on native plants growing alongside parked cars. Over the previous winter, students and teachers worked together to get these botanical islands officially certified as Pollinator-Friendly and the school maintenance crew is relieved there is one less place to weed whack!

When school resumes in September, 1st graders visit the milkweed patch, where ripened seeds shine in the low light, to observe monarchs feeding on asters and goldenrods. A once-eroded slope is now a place of school pride that also hosts native blueberries. The local blueberry grower has a Q & A Session with the 6th graders as they sip blueberry smoothies.

When school resumes in September, 1st graders visit the milkweed patch, where ripened seeds shine in the low light, to observe monarchs feeding on asters and goldenrods. A once-eroded slope is now a place of school pride that also hosts native blueberries. The local blueberry grower has a Q & A Session with the 6th graders as they sip blueberry smoothies.

In the vegetable garden, 6th-grade art students draw sunflowers for a still-life lesson. If only the bumblebees would stay in one place long enough to be included in the picture!

In October, 5th graders measure the growth of young sugar maples using calipers and carefully record their findings. It will be a while before the trees shade the soccer field, or before a line of taps can be set up, but their colorful leaves already glow as a symbol of resilience.

Five years ago, the school board approved funds to plant a ReTreeUs Orchard of Liberty and Black Oxford apples. These offer a double reward: snacks in the fall and blossoms next spring.

In November, the 8th graders harvest vegetables for making stone soup during the nutrition lesson.

In November, the 8th graders harvest vegetables for making stone soup during the nutrition lesson.

Finally, before everything freezes up, a PE class visits the Outdoor Classroom one last time for the annual wood chips bucket brigade.

A transformation like this takes a team of committed stakeholders with a little bit of imagination and lots of observations, a good plan, and a fistful of seeds. Our schools in Maine are sitting on a gold mine: a fertile terrain of pedagogical opportunities as we nurture a more intimate relationship between ourselves and nature.

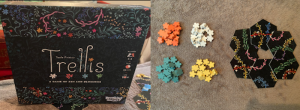

Game Review: Trellis

(Publisher: Breaking Games) by Teale Fristoe

Reviewer: Jonathan Foster, UMaine Extension Community Education Assistant

In the second installment of our gardening-related board game reviews, we introduce Trellis (2-4 players, aged 10+), a deceptively nuanced tile-laying game designed by Teale Fristoe and published by Breaking Games. Players take turns placing tiles with colorful vine segments to make a tangle of plant life and nurture “blooms” of their own color. The first player to place their entire stock of flower tokens wins. This won’t take long, as the game only runs 10-20 minutes–perfect for a quick filler before heading home from camp or shoveling a snowy walk.

Each player takes 15 wooden flower tokens of their color and draws 3 cardboard tiles from the supply. Brightly colored vines weave their way across the hexagonal tiles and grow into a unique tangle each game as they are placed. A starting tile is placed and whoever last watered a plant starts the game. Players take turns laying tiles so that a vine on the new tile connects with a vine on an existing one (colors need not match, though it’s beneficial if they do).

The active player places one of their flower tokens on any of the vine segments of the newly placed tile to claim it (image 1 below). Placing a tile that continues a colored vine on an existing tile lets you place another token for free on the previously unclaimed vine portion (image 2 below).

If a player places a tile that connects a vine claimed by another player to its matching color, it grants that other player an automatic flower token (Images 3 and 4 below). And lastly, if a player places a tile that allows another player a free token, as in our example above, they *also* get to place a free token (Image 5).

As you can see, a game that starts slowly gets significantly quicker as the tangle grows and vines are connected in various ways. This complex scoring dynamic brings a nice tension into the game–helping another player gets them closer to victory, but also lets you place a free token of your own. Keeping track of how many tokens everyone has left is essential… as is cajoling others to help you out for the sake of helping themselves out!

Trellis can either be a calm, peaceful game with kids or a cutthroat match with other experienced players. Enjoy the lovely artwork and deliciously tactile wooden tokens, as well as the brain burn of trying to both cooperate with and oppose others to place your flowers first. Regardless of your approach, it’s worth a try!

(All photos by Jonathan Foster, all rights reserved to designer and publisher.)

House Sparrow

By Doug Hitchcox, Maine Audubon Staff Naturalist

House Sparrows are a common sight in many backyards. Their constant presence and invasive designation makes them easy to overlook, but they can be an entertaining study, especially going into the fall as they change their appearance. Most of our native species need to molt (or replace) their feathers twice a year: once in the spring to get their breeding (or alternate) plumage; and again in the fall for their non-breeding (or basic) plumage. House Sparrows, in contrast, only molt once annually, in the fall. A fun feature to study is the breast feathers on the males, who typically look like they’re wearing a dark bib. These newly-replaced feathers will have pale gray tips to them, representing this bird’s non-breeding plumage. Those tips will wear away over the winter and reveal the complete black bib by spring, then it’ll be in its breeding plumage! Molting takes a lot of energy, so this two-for-one technique is quite a helpful adaptation.

For more on the importance of Maine native plants to support birds and other wildlife, visit Maine Audubon’s “Bringing Nature Home” webpage.

Do you appreciate the work we are doing?

Consider making a contribution to the Maine Master Gardener Development Fund. Your dollars will support and expand Master Gardener Volunteer community outreach across Maine.

Your feedback is important to us!

We appreciate your feedback and ideas for future Maine Home Garden News topics. We look forward to sharing new information and inspiration in future issues.

Subscribe to Maine Home Garden News

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications, click on the Subscribe button below.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

For more information or questions, contact Kate Garland at katherine.garland@maine.edu or 1.800.287.1485 (in Maine).

Visit our Archives to see past issues.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around Maine. The following staff and volunteer team take great care editing content, designing the web and email platforms, maintaining email lists, and getting hard copies mailed to those who don’t have access to the internet: Abby Zelz*, Annika Schmidt*, Barbara Harrity*, Cindy Eves-Thomas, Kate Garland, Mary Michaud, Michelle Snowden, Naomi Jacobs*, Phoebe Call*, and Wendy Roberston.

*Master Gardener Volunteers

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2022

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

The University of Maine is an EEO/AA employer, and does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender expression, national origin, citizenship status, age, disability, genetic information or veteran’s status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Director of Equal Opportunity, 101 Boudreau Hall, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5754, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).