Maine Home Garden News — September 2016

- September Is the Month to . . .

- Understanding How Drought Impacts Our Landscape

- Redvein Enkianthus: A Functional Plant for All Seasons

- Master Gardener Volunteer Project Profile: Westrum House in Topsham

- Food & Nutrition: Preserving Relish Safely

September Is the Month to . . .

By Lynne Holland, Community Education Assistant (Home Horticulture), UMaine Extension in Androscoggin and Sagadahoc Counties, and Kathy Hopkins, Extension Professor, UMaine Extension in Somerset County

- Harvest the garden regularly. Donate excess produce through the Maine Harvest for Hunger program. For more information, please visit Maine Harvest for Hunger.

- Harvest and dry herbs while they are at their peak. If you have been gathering perennial herbs regularly through the summer, mid September should be the last cut of the year. Any new growth after that will likely be damaged by cold weather. The drier days of autumn are a good time for drying herbs. Get some hints on drying garden produce from our video “How to Dry Vegetables.”

- Remove plant debris and weeds from the garden to reduce the number of overwintering sites for unwanted insect and disease populations, and minimize the deposit of seeds into the soil “weed seed bank.” Follow with a cover crop to protect the soil and serve as competition for weeds. If planting a cover crop is not an option, topdress with an organic mulch, such as seaweed, straw or leaves. Mulch will also add nutrients to the soil and improve soil structure.

- Watch the weather and take steps to protect tender plants if there’s a chance of frost. Bulletin #2752, Extending the Garden Season describes methods to protect plants from the cold and extend the growing season.

- Do a soil test. If the results indicate the need for lime and manure additions, September is a great time to apply those amendments. For more information on soil testing, see Bulletin #2286, Testing Your Soil. For safe manure practices, see Bulletin #2510, Guidelines for Using Manure on Vegetable Gardens. For more information on soil organic matter, see Bulletin #2288, Soil Organic Matter.

- Review the year. Which vegetables were high producers? What plant varieties were your favorites? List successes, failures, diseases, and insect pests. Brainstorm a plan for next season. Take pictures and add to an electronic garden journal or calendar. Pictures will help you remember the good and bad of the season.

- Save seeds of non-hybrids to plant next year. Learn how to have success saving seeds by reading Bulletin #2750, An Introduction to Seed Saving for the Home Gardener.

- Dig up bulbs that are not winter hardy like cannas, gladiolus, and dahlias after the foliage dies back. Clean the bulbs before storing. Store for the winter in peat moss or dry sand in a dark, cool, well ventilated space where the temperatures remain above 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

- Build raised beds now, so they will be ready to plant in early spring. For more information, watch our four-part video series Extending the Gardening Season Using Raised Beds. Includes a link to plans and materials list.

- Cut back on your lawn area and come over to the “Low Input Lawn” team. Reducing lawn area will save you time and effort next year. Starting to implement the practices of a “Low Input Lawn” now will help your soil recover over the winter so you can have a healthier lawn next year. See Bulletin #2166 Steps to a Low Input Lawn for detailed information.

- Stop watering and fertilizing any established perennials, trees and shrubs in September. Watering and or fertilizing now will encourage new growth, making the plant susceptible to winter damage. Established perennial plants use this month to prepare for dormancy and winter.

- Plan to water trees (deciduous and evergreen) deeply once all the leaves on the deciduous trees have dropped, but before the ground freezes (later in October or November for most areas). This can help trees recover from some of the stress they may have experienced during the prolonged dry spell this summer. Read article below for tips on watering deeply.

- Register for free disposal of banned, unusable pesticides through the Maine Board of Pesticides Control. This free annual program takes place at several locations across the state, but registration is mandatory. Learn more.

Understanding How Drought Impacts Our Landscape

By Kate Garland, Horticulturist, and Jonathan Foster, Home Horticulture Coordinator, UMaine Extension Penobscot County

It has been a dry season in Maine. Hopefully, this pattern has changed by the time you are reading this piece, but even if it has, it’s important to take a moment to understand how drought can influence our ornamental and edible landscapes and to learn strategies to minimize water stress in the future. Water stress impacts plant growth in several ways and can vary between species (and even among individuals of the same species), but it always carries the potential for negative consequences. Gardeners may notice reduced yield, slower growth, poor fruit quality, or simply overall plant decline.

Just like all other living organisms, plants are made up of tiny building blocks called cells, which must divide and expand for the plant to grow. Plants don’t have a bony skeleton like large animals do, so they rely on constant internal water pressure to stay upright; if a plant does not have enough water in its cells, the cells shrink and the plant will wilt. Turgor is the constant water pressure within a plant cell that gives the cell its shape and the plant its structure. In order for cells to continue dividing and permanently expanding (i.e., for the plant to grow), they must have sufficient turgor not just to maintain the plant’s architecture, but also to pressure the cell wall to expand outward.

Unsurprisingly, plants developing under sustained water stress will have smaller cells—resulting in smaller leaves, shorter stature, and less developed fruit. The produce in our gardens is basically nicely packaged water with good nutritional value. For example, the moisture content for roots and tubers is typically 73-95%, leaves and stems is between 77-96%, and fruits top the moisture content at around 90-96%. Knowing this, it’s easy to see how vulnerable commercial producers are to crop loss in drought situations. Finally, moving beyond limited cell expansion, water stress can also slow down or alter a number of vital metabolic processes within plants, including the all-important photosynthesis.

Examples of impact on fruit quantity and quality

Under water stress, plants will deploy different strategies to minimize the energy required to survive and/or maximize their capacity to pass their genes on to the next generation, generally reducing the number or quality of their fruit in order to conserve resources for overall plant survival. For example, cucurbits (cucumbers, zucchini, pumpkin, squash, and melons) produce more male flowers than female flowers during an especially dry season. The female flowers are what yield the fruit when fertilized, but fruit production requires a lot of energy and water. Allocating resources towards more male flowers than female allows individual plants a greater chance of spreading their genes via pollen without having to put the energy into developing fruit (if the pollen reaches the female flower on another plant).

Several types of plants (eggplant, peppers, beans, to name just a few) drop their flowers when water is limited or another compounding stress, such as heat, is involved, thereby reducing the likelihood of fertilization and costly fruit set. Leafy greens, such as spinach and lettuce sometimes transition into the flowering stage of their life cycle (bolt) significantly faster in drought conditions. Plants may also react to drought stress by directing more of their growth energy towards root development instead of towards stem, leaf, flower, and fruit production. This evolutionary strategy carries the dual benefit of increasing the capacity for the plant to mine water from the soil while reducing the surface area exposed to water loss, but can also leave the plant without enough photosynthetic foliage to support the rest of its biomass. And finally, the diminished amounts of energy that stressed plants allocate into producing expensive fruit tissues often results in outcomes like bitter-tasting fruits, blossom end rot (squash, zucchini, tomato, and pepper), and cracked tomatoes, among other examples of poor fruit quality associated with water stress.

Overall plant decline

Newly planted trees, shrubs, perennials, and annuals (including vegetable transplants) all need supplemental water the first year they are in the ground. Symptoms of water stress in newer transplants include wilt, scorch, and premature leaf drop. As a general rule, most newly installed plants will benefit from having 1″ of water a week throughout the entire first growing season. A simple rain gauge will usually provide evidence that our rain events do not supply nearly that amount of moisture on a reliable basis. Furthermore, the larger the transplant, the longer it will take to have a well developed and established root system capable of sustaining the water requirements of the entire plant. When trees are over 1” in diameter, it’s a good practice to plan on supplementing the water for the same number of years as the trunk measures in diameter (ex: 4 years for a 4” caliper tree).

Established trees, shrubs, and perennials can also suffer from sustained periods of drought, but unlike newer transplants, the symptoms can take a long time to appear and are hard to relate back to drought. Damage happens when the delicate root hairs growing in the top 15” of the soil profile are destroyed over prolonged dry periods. These small roots play an enormous role in the water absorption capacity of the plant, but their loss can be masked in the short term by the capacity for a mature plant to tap into water stores within the trunk, other stem tissue, and larger roots.

What you can do

Mulch. Bark, wood chips, straw, lawn clippings, and even re-used materials such as cardboard and newspaper are all examples of useful organic mulching materials. Black plastic is also an effective barrier to evaporation that also reduces weed pressure near vulnerable plants (minimizing competition for moisture and nutrients).

Mulch. Bark, wood chips, straw, lawn clippings, and even re-used materials such as cardboard and newspaper are all examples of useful organic mulching materials. Black plastic is also an effective barrier to evaporation that also reduces weed pressure near vulnerable plants (minimizing competition for moisture and nutrients).

Water. Differences in soils and plant types make it difficult to give a single prescription for watering that will work for every site, but here’s some general advice. To provide 1” of water a week to new transplants, water the soil (not the plants) with a slow trickle approximately 2-3 times a week for roughly 15-20 minutes. The water should not pool up on top of the soil, but should penetrate deep into the roots. Decrease the water pressure if pooling is observed. To check whether the water is reaching down to the appropriate depth, dig a 6” deep hole after watering to see if the moisture has truly reached the root zone. Prioritize watering zones if it’s difficult to keep up with watering and consider adding permanent drip lines near high-value established plants. Rain barrels are a great solution to capturing run-off from rooftops for use on ornamental plantings.

Water. Differences in soils and plant types make it difficult to give a single prescription for watering that will work for every site, but here’s some general advice. To provide 1” of water a week to new transplants, water the soil (not the plants) with a slow trickle approximately 2-3 times a week for roughly 15-20 minutes. The water should not pool up on top of the soil, but should penetrate deep into the roots. Decrease the water pressure if pooling is observed. To check whether the water is reaching down to the appropriate depth, dig a 6” deep hole after watering to see if the moisture has truly reached the root zone. Prioritize watering zones if it’s difficult to keep up with watering and consider adding permanent drip lines near high-value established plants. Rain barrels are a great solution to capturing run-off from rooftops for use on ornamental plantings.

Improve soil structure. Gardeners should aim to have a Goldilocks soil: not too porous, not too compacted, but just right. Regularly introducing organic matter is the best tool to improve soil moisture management on either end of the spectrum, as it will improve the capacity for highly porous soils to hold onto water while improving the porosity of heavy clay soils. Fall is an excellent time to add a variety of types of organic matter: compost, aged manure, seaweed, and (my favorite) shredded leaves are all additives that will improve the resiliency of your landscape to sustain itself when — not if — another dry spell hits Maine again.

Improve soil structure. Gardeners should aim to have a Goldilocks soil: not too porous, not too compacted, but just right. Regularly introducing organic matter is the best tool to improve soil moisture management on either end of the spectrum, as it will improve the capacity for highly porous soils to hold onto water while improving the porosity of heavy clay soils. Fall is an excellent time to add a variety of types of organic matter: compost, aged manure, seaweed, and (my favorite) shredded leaves are all additives that will improve the resiliency of your landscape to sustain itself when — not if — another dry spell hits Maine again.

Read more

- Long-term drought effects on trees and shrubs

- Drought tolerant plants for the landscape

- Drought tolerant perennials

- Drought tolerant annuals and perennials

- Efficient outdoor watering

- Indoor and outdoor residential water conservation checklist

- Managing soil structure for water conservation in the landscape

Redvein Enkianthus: A Functional Plant for All Seasons

By Marjorie Peronto, Extension Educator, UMaine Extension Hancock County, and Reeser Manley, Horticulturist

Our garden is carved out of the woods. It is a thing of beauty to us, but more importantly, it is a functional garden. All the ornamental plants we select, whether herbaceous or woody, have one thing in common: they build garden biodiversity. They have a role in supporting the many forms of garden life including soil organisms, insects, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.

Though we lean towards natives, plants “from away” can also be ecologically functional. For example, we have found Redvein enkianthus (Enkianthus campanulatus), native to open woodlands in Japan, to be absolutely “abuzz” with Maine bumblebees in the spring. This small tree, now in its fifteenth year in our garden, stands about 10′ tall. When in flower, clusters of yellow to white bells with deep red veins hang from each branch tip. The flowers, similar in shape to those of its close relative, the native Maine highbush blueberry, serve as a nectar source to bumblebees.

We have pruned this naturally shrubby plant into a small multi-trunk tree. Redvein enkianthus can also make a beautiful informal hedge if kept in its shrubby form.

- Photo by Reeser Manley.

- When the flowers drop, they leave a rosy carpet on the ground. Photo by Reeser Manley.

After flowering, seed capsules develop and ripen in late summer. What birds or rodents eat the seeds after they are dispersed remains a mystery. We have had the pleasure of seeing many different species of songbirds flitting among the branches throughout the spring and summer.

In autumn the leaves on our plant turn to a mix of brilliant red and gold. Fall color is variable within the species with some plants turning all red or all yellow. Cultivars have been selected for red fall foliage, others for deep red flowers.

Redvein enkianthus is recommended by University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension and by Massachusetts’ nurseries as a replacement for the non-native invasive burning bush (Euonymus alatus), or Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii). Any gardener familiar with enkianthus knows that neither burning bush nor Japanese barberry can hold a candle to the brilliant red and gold of enkianthus’ autumn leaves. It deserves a place on any gardener’s list of “Functional Plants for All Seasons.”

Master Gardener Volunteer Project Profile:

Westrum House in Topsham

By Tori Lee Jackson, Associate Professor of Agriculture & Natural Resources, and Lynne Holland, Home Horticulture CEA, UMaine Extension in Androscoggin and Sagadahoc Counties

Volunteers of America (VOA) is responsible for improving the lives of many people in Maine, and around the country. The President of the Androscoggin-Sagadahoc Counties Extension Association (ASCEA), Michael Coon, is Vice President of External Relations and director of Camp POSTCARD at VOA. He has been interested in making program connections with Extension since joining the ASCEA several years ago. Collaboration began with 4-H Educator Kristy Ouellette and Camp POSTCARD, and has now expanded to include the Master Gardener Volunteers program.

One of VOA’s local projects is a beautiful facility for low-income seniors in Topsham, known as Westrum House. In February of 2016, Travis Drake and Bill Browning, staff members at VOA, contacted the Lisbon Falls Extension office for information on getting a garden started for the seniors living there. Master Gardener Volunteer (MGV) Program Coordinator Lynne Holland met with staff and residents to determine where the gardens would be placed. Local volunteers began planning the perfect garden space for the seniors who missed growing vegetables of their own.

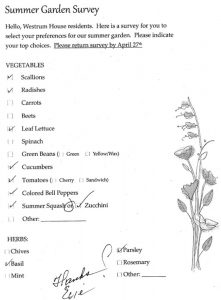

There has been great enthusiasm for this project from the start and as soon as the snow was gone, planning and construction of beautiful, handicapped-accessible raised beds got underway. MGV Deanna Cyr created a simple survey and distributed it to residents to see what kinds of vegetables would be most desired. She created a shopping list with the results and a combination of seedlings and seeds were bought. The beds were filled with media and planted in mid-June during a work party with participation from about a quarter of the residents.

There has been great enthusiasm for this project from the start and as soon as the snow was gone, planning and construction of beautiful, handicapped-accessible raised beds got underway. MGV Deanna Cyr created a simple survey and distributed it to residents to see what kinds of vegetables would be most desired. She created a shopping list with the results and a combination of seedlings and seeds were bought. The beds were filled with media and planted in mid-June during a work party with participation from about a quarter of the residents.

With so many residents, volunteers, and staff involved and excited about this project, the regular maintenance of weeding and watering has been handled very easily and residents are now enjoying the harvest of lettuce, radishes, herbs, summer squash, peppers, and tomatoes. Rachel L., a resident of Westrum house reported, “This morning… harvested about 10 cucumbers. I don’t know if the tomatoes will ripen. Harvested 3 zucchinis. I had some little poles and placed them around the string beans until I get something taller.” Rachel has also been avidly watching University of Maine Cooperative Extension videos on YouTube to see how to improve the harvest and the garden for next year. (And, by the way, the tomatoes are ripening nicely.)

A couple of comfortable chairs are next to the beds and in the early morning and late evening you can find residents stopping off to sit for awhile after walking their dogs or waiting to go out to appointments or to eat.

This garden has been such a hit that staff of VOA have invited the ASCEA to hold their September meeting on site and to serve fresh vegetables from their garden for dinner.

The new raised bed gardens at Westrum House are a great example of how a relatively small project can have a very big impact on the lives of Maine seniors. It will be part of the VOA focus on Seniors in their October/November newsletter and can serve as a model for creating gardens at VOA housing facilities across the state.

Food & Nutrition:

Preserving Relish Safely

By Kate McCarty, Food Preservation Community Education Assistant, UMaine Extension Cumberland County

By Kate McCarty, Food Preservation Community Education Assistant, UMaine Extension Cumberland County

Preserving relish is a great way to use up end-of-season garden vegetables while creating a flavorful condiment to use on sandwiches, in salads, and even as a tart side to your cheese plate. Because relishes are made from a combination of low-acid ingredients, like cucumbers, onions, and peppers, and vinegar, which is acidic, particular attention must be paid to the quantity of each in order to ensure your relish is safe for canning. Follow a recipe from a trusted source, like Cooperative Extension or USDA, and do not change the amount of any ingredients. Spices can be added or left out without affecting the safety of the final product, so you can personalize your relish by adding spices to your liking. Relish can be safely processed in a boiling water bath canner.

The recipe below is great for using up small amounts of produce that may be leftover in the fall as you put your garden to bed. The recipe calls for salting and refrigerating your vegetables for several hours before preparing the relish, so plan ahead. This process draws water from the vegetables so they stay crunchy after being cooked. Skipping these steps will result in a relish with an unpleasant texture. Canning salt is salt with no additives, like iodine or anti-caking agents, which can cause discoloration of your pickles or relish.

The recipe below is great for using up small amounts of produce that may be leftover in the fall as you put your garden to bed. The recipe calls for salting and refrigerating your vegetables for several hours before preparing the relish, so plan ahead. This process draws water from the vegetables so they stay crunchy after being cooked. Skipping these steps will result in a relish with an unpleasant texture. Canning salt is salt with no additives, like iodine or anti-caking agents, which can cause discoloration of your pickles or relish.

For more relish recipes, visit the National Center for Home Food Preservation’s How to Can Relish. To learn more about hot water bath canning, visit Let’s Preserve: Food Canning Basics or attend a hands-on workshop in your area.

Fall Garden Relish

Adapted from the National Center for Home Food Preservation

4 cups chopped cabbage (about 1 small head)

3 cups chopped cauliflower (about 1 medium head)

2 cups chopped green tomatoes (about 4 medium)

2 cups chopped onions

2 cups chopped sweet green peppers (about 4 medium)

1 cup chopped sweet red peppers (about 2 medium)

3-¾ cups vinegar (5% acidity)

3 tablespoons canning salt

2-¾ cups sugar

3 teaspoons celery seed

3 teaspoons dry mustard

1-½ teaspoons turmeric

Yield: About 4 pint jars

Procedure: Combine washed chopped vegetables; sprinkle with the 3 tablespoons salt. Let stand 4 to 6 hours in the refrigerator. Drain well. Combine vinegar, sugar and spices; simmer 10 minutes. Add vegetables; simmer another 10 minutes. Bring to a boil.

Pack boiling hot relish into hot jars, leaving ½-inch headspace. Remove air bubbles and adjust headspace if needed. Wipe rims of jars with a dampened clean paper towel; adjust two-piece metal canning lids. Process pints for 10 minutes in a Boiling Water Canner.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications fill out our online form.

For more information or questions, contact Kate Garland at katherine.garland@maine.edu or 1.800.287.1485 (in Maine).

Visit our Archives to see past issues.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around Maine, with Katherine Garland, UMaine Extension Horticulturalist in Penobscot County, serving as editor.

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2016

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.