Maine Home Garden News — October 2019

- October Is the Month to . . .

- Is Your Yard a Bare Cupboard for Pollinators?

- The Western Conifer Seed Bug

- 2020 Maine Garden Day: Save the Date!

- Gaultheria Procumbens, a Small Evergreen with a Large Scent

- Fun and Challenges of Building a Community Garden

- Food & Nutrition: Fall is for Food Safety

October Is the Month to . . .

By Kate Garland, Horticulturist UMaine Cooperative Extension Penobscot County

- Keep weeding. I know many of you are ready to toss in the trowel and let nature take its course at this point in the season, but consider the concepts “weed seed rain” and “soil seed bank” before calling it quits. Many of our common weeds “rain” hundreds, thousands, and even hundreds of thousands of seeds per plant. Seed longevity depends on species and environmental conditions, but they can often remain viable in the soil seed bank for 30-40 years simply waiting for the right conditions to germinate.

- Promptly remove wanted plants that can become weeds if allowed to set seed. Cosmos, dill, cilantro, and tomatoes are just a few of the many examples of plants with seeds hardy enough to survive our winters and eventually result in countless seedlings in subsequent years. This trait can be appreciated by gardeners who appreciate a more wild aesthetic, but can madden those looking for more managed and clean lines in the garden.

- Apply animal manures in the vegetable garden. To minimize risk of food-borne illnesses, Guidelines for Using Manure on Vegetable Gardens suggests fall applications of animal manures are your safest bet. Never use cat, dog or pig manure in vegetable gardens or compost piles. Parasites that may be in these types of manure are more likely to survive and infect people than those in other types of manure. It is also important to keep your pets out of your vegetable garden.

- Add features to extend your season. Even if you’re not planning on Extending the Gardening Season this fall, establishing the infrastructure now will make it that much easier to get a jump on the season next spring.

- Shred and store fallen leaves for a year-round supply of brown (relatively high carbon) materials for your backyard compost pile. Leaves pair well with common kitchen scraps as part of a well-balanced diet for the microorganisms behind the decomposition process.

- Remove plant debris. This is especially important if your plants have experienced insect or disease pressure this season. Some pests and pathogens overwinter in the debris and simple housekeeping can make a big difference with managing those problems next year.

- Have your soil tested. You’ve heard us say it a million times, but I’ll say it again. Testing your soil helps gardeners understand what might be limiting optimal plant growth and will provide specific recommendations regarding what and how much should be added to eliminate any nutritional deficiencies or bring pH to an appropriate level. A standard soil test will also provide a lead scan and estimate the percentage of organic matter in your soil. Request a kit here.

Plant spring flowering bulbs. Did you know that 2019 is the 100th anniversary of Maine ratifying the 19th Amendment? Did you know the daffodil was the flower of the suffrage movement? Celebrate “votes for women!” this fall by planting daffodils in your home, work or community landscape. Learn more.

Plant spring flowering bulbs. Did you know that 2019 is the 100th anniversary of Maine ratifying the 19th Amendment? Did you know the daffodil was the flower of the suffrage movement? Celebrate “votes for women!” this fall by planting daffodils in your home, work or community landscape. Learn more.

- Treat yourself next spring by cleaning and sharpening tools before storing for the winter. Read some great tips and tricks here. Don’t forget to take advantage of the few remaining warm sunny days to drain, coil, and store that garden hose!

- Take plenty of photos and notes about what worked and what could be better next year. You’ll thank yourself when you’re busy developing a game plan this winter!

Is Your Yard a Bare Cupboard for Pollinators?

By Rebecca Long, Agriculture and Food Systems Professional, UMaine Extension Oxford County

This is not an article like Understanding Native Bees, the Great Pollinators: Enhancing Their Habitat in Maine, about the importance of native pollinators, but rather one that hopes you are already convinced of that. Just in case, I’ll mention that 75% of flowering plants require animal pollinators to reproduce and 1/3 of our food is the direct result of animal pollination. Instead, this is an article about what we can do, in our own backyards, to bolster native pollinator populations. To get to the answer, we’ll start with two important concepts.

This is not an article like Understanding Native Bees, the Great Pollinators: Enhancing Their Habitat in Maine, about the importance of native pollinators, but rather one that hopes you are already convinced of that. Just in case, I’ll mention that 75% of flowering plants require animal pollinators to reproduce and 1/3 of our food is the direct result of animal pollination. Instead, this is an article about what we can do, in our own backyards, to bolster native pollinator populations. To get to the answer, we’ll start with two important concepts.

For the first, let’s go way back to when we learned about the food web in school. At the foundation are plants, the primary producers that capture the sun’s energy through photosynthesis and convert it into biomass. Herbivores, including insects, eat the plant biomass, and in turn get eaten by carnivores. Plants are the key that allows the rest of us herbivores, carnivores, and omnivores to access the sun’s energy.

The second important concept: not every animal can eat every plant. Each plant has a unique chemical makeup, part of which forms a chemical defense system from being eaten. To avoid competition, insects have evolved, over thousands of years, to eat specific plants, by evolving enzymes which detoxify those defense mechanisms. Because this evolutionary process takes so long, insects must coexist with a plant for thousands of generations before they evolve the ability to eat it. In fact, 90% of insects can survive only on those plants that are native to their region.

If plants form the basis of our food chain, and most insects can only eat plants native to their region, it follows that if we want native insects (and even the birds that eat those insects), we must plant native species. Unfortunately for native insects, our yards and landscapes are full of non-natives, many of which are specifically bred to not be palatable to insects (because who wants holes in their plants?).

Doug Tallamy put it simply in his book Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants: “planting alien species is like someone coming in and replacing every ingredient in your cabinet with things you are unfamiliar with, and possibly unable to eat.” As we further encroach on natural areas, converting forests and fields to housing and yards, and replacing native plants with non-natives and lawn, we are clearing out the cupboards that native insects and pollinators rely on for food.

Native plants don’t just provide food for native insects, they also provide shelter and a place to raise young. Many insects lay their eggs on host plants and once those eggs hatch they rely on those plants for food. Just like adults, many insect larvae cannot complete their life cycle without native plants. Most of us are familiar with the classic pairing of monarchs and milkweed, but there are countless other examples.

Other unintended consequences of landscaping with non-natives include the potential for them to become invasive (Japanese knotweed, Fallopia japonica) or bring in diseases that affect our natives (like the one that very nearly wiped out the American chestnut, Castanea dentata). Without natural enemies, non-natives can also easily out compete our native species for food, light, water, and space.

A bonus of adding natives to your landscape is that since they are growing in the region they are adapted to, they often require less water and maintenance. And if your fear is that natives will be drab and unexciting, a colorful display of purple asters and yellow goldenrod will convince you otherwise.

If you are spurred to action, start by identifying what already exists in your yard. Go Botany, from the Native Plant Trust, is a useful key for New England Plants. You can also reach out to your local Cooperative Extension office for help. Next, think about replacing non-natives with a native species. You can often find alternatives with similar form and function to maintain the look of your landscape. If you are feeling particularly ambitious, consider expanding foundation plantings or even converting an area of lawn to a native garden!

“By planting natives…you can restore the components of habitat and invite the wildlife back to the land it once occupied.” (Attracting Birds, Butterflies and Other Backyard Wildlife, David Mizejewski)

For more information, checkout Gardening to Conserve Maine’s Native Landscape: Plants to Use and Plants to Avoid and Native Plants: A Maine Source List.

The Western Conifer Seed Bug

By Leala Machesney, Horticulture Graduate Student, The University of Arkansas

Western conifer seed bugs (Leptoglossus occidentalis) will soon begin migrating inside buildings to overwinter and, subsequently, samples of these insects will begin to trickle into UMaine Extension offices statewide. These insects do not pose a threat to human health and are not known to damage buildings, but they can become a nuisance — especially if they arrive in significant numbers.

Western conifer seed bugs (Leptoglossus occidentalis) will soon begin migrating inside buildings to overwinter and, subsequently, samples of these insects will begin to trickle into UMaine Extension offices statewide. These insects do not pose a threat to human health and are not known to damage buildings, but they can become a nuisance — especially if they arrive in significant numbers.

As their name suggests, western conifer seed bugs feed on conifer seeds. The native range of the western conifer seed bug extends from British Columbia south to Mexico and east to Colorado. Western conifer seed bugs first reached New England in the 1990s, but their expansion continued across the Atlantic Ocean. The western conifer seed bug now occupies the majority of Europe and is considered an invasive species in many countries. Recently, a poor year for pine nut harvest in Tuscany was attributed, in part, to heavy feeding from western conifer seed bugs.

Overwintering adults can be found in dead conifer trees, under pine bark, in bird and rodent nests, and in buildings. They emerge from overwintering sites in late May and early June when they will begin mating and laying eggs on host trees. Eggs will hatch in approximately ten days and the next generation of Western conifer seed bugs will continue to feed on conifers until the fall. Although these insects pose no danger to humans, they can greatly reduce the germination capability of predated seeds.

The western conifer seed bug is not currently considered an invasive insect in Maine. Although extensive research has been conducted to investigate the effects of western conifer seed bug feeding on native host species, like Douglas fir, the effect of feeding on Maine conifers, like white pine, is limited. Feeding damage from western conifer seed bugs isn’t visible to the naked eye and potential damage difficult to quantify. Both the adult insects and juvenile nymphs use specialized mouthparts called stylets to pierce through cones and suck lipids and proteins out of conifer seeds. Mature cones that western conifer seed bugs have been fed upon show no external signs of feeding damage. However, even seeds that were lightly fed upon by the western conifer seed bug exhibit a greatly reduced capacity to germinate.

To prevent these unwanted visitors from entering homes and buildings, the best line of defense is to focus on sealing cracks around windows, doors, fascia and soffit boards, and other structural openings such as around chimneys and vents.

Further Reading

- Lesieur, V., Yart, A., Guilbon, S., Lorme, P., Auger-Rozenberg, M., & Roques, A. (2014). The invasive leptoglossus seed bug, a threat for commercial seed crops, but for conifer diversity? Biological Invasions, 16(9), 1833-1849.

- Barta, M. (2016). Biology and temperature requirements of the invasive seed bug leptoglossus occidentalis (heteroptera: Coreidae) in europe. Journal of Pest Science, 89(1), 31-44.

- Lesieur, V., Lombaert, E., Guillemaud, T., Courtial, B., Strong, W., Roques, A., & Auger-Rozenberg, M. -. (2019). The rapid spread of leptoglossus occidentalis in europe: A bridgehead invasion. Journal of Pest Science, 92(1), 189-200.

2020 Maine Garden Day: Save the Date!

We are pleased to announce that we are bringing back Maine Garden Day (after a five-year hiatus). This information-riche gardening conference will be held on Saturday, March 14, 2020 at Lewiston High School. Stay tuned for more details and registration information on the Garden & Yard website.

Gaultheria Procumbens, a Small Evergreen with a Large Scent

By Kookie McNerney, Home Horticulture Coordinator, UMaine Extension Cumberland County

While hiking, have you ever noticed the sweet scent of wintergreen below your feet? If you have, it most likely emanated from Gaultheria procumbens, more commonly known as Wintergreen or Eastern Teaberry. It is indeed the most noteworthy characteristic of this Maine native plant. Both the leaves and the berries exude a crisp, refreshing wintergreen scent. If it were not for the scent, you might just miss this otherwise diminutive sub-shrub species.

While hiking, have you ever noticed the sweet scent of wintergreen below your feet? If you have, it most likely emanated from Gaultheria procumbens, more commonly known as Wintergreen or Eastern Teaberry. It is indeed the most noteworthy characteristic of this Maine native plant. Both the leaves and the berries exude a crisp, refreshing wintergreen scent. If it were not for the scent, you might just miss this otherwise diminutive sub-shrub species.

Wintergreen has medicinal properties due to the anti-inflammatory compound, methyl salicylate, which is now largely synthetically produced. Consumption of the essential oil of Gaultheria is toxic in large doses, but this species was once commonly used as the flavoring for chewing gums, toothpastes, medicines, and teas. It can still be found in some common candies.

Gaultheria procumbens is a member of the Heath family. It is a rhizomatous, creeping woody evergreen, which forms small colonies. It grows best in part-shade to shade and prefers somewhat acidic soils. This makes it an excellent selection as an understory planting in a woodland or naturalized garden. It also is a wonderful compliment to azalea, rhododendron, laurel, and high bush blueberry. The dark green, alternate leaves are glossy and leathery with extremely fine teeth. The solitary white flowers are petite, nodding, and urn-shaped. Although it grows well in deep shade, the plants will flower more profusely with some dappled sun. Bright red, showy, edible berries are formed from the flowers. The fruits can be eaten raw or added to pastries or salads. The berries also support many species of wildlife, including pheasant, grouse, wild turkey, squirrels, white-tailed deer, mice, and red fox. In the fall, Gaultheria procumbens turns lovely shades of red to reddish-purple. All of these traits make this a very desirably 3-season plant.

Here are some fun facts about Gaultheria procumbens.

- In 1999 the Maine state legislature adopted Gaultheria procumbens as the official state herb of Maine.

- Do you remember Wint-O-Green Lifesavers? Candy maker Clarence Cane in Cleveland, Ohio invented Wint-O-Greens in 1919.

- Have you ever heard of triboluminescence? Triboluminescence is the phenomenon of light being generated (a spark) when crushing Wint-O-Green Lifesavers in the dark. This is due to the essential oils, which are found in Gaultheria procumbens. Give it a try sometime.

Additional resources:

- UMaine Cooperative Extension: Gaultheria procumbens

- Maine State Herb

- Native Plants in Maine (YouTube video)

Fun and Challenges of Building a Community Garden

By Kevin McKeon, Master Gardener Volunteer, Class of 2019

After acquiring what is now known as The McKeon Environmental Reserve, the Directors of the Mousam Way Land Trust endorsed the concept to plan and build a community ecology center. The David and Linda Pence Community Ecology Center, named after the generous folks who put the fundraising for Reserve property acquisition over the top, will include an Environmental Center where folks can hold meetings; a small workshop for making bird nesting boxes, bat houses, informational signs, and other eco-oriented projects; an environmental library, attuned towards school kids; an ADA-accessible outdoor restroom; an industrial-sized greenhouse; and a nursery to propagate various plants for the Nature Trail and other ongoing projects:

- Meadow restoration being helped along by, among others, 2nd grade kids from local schools;

- Self-guided Nature Trail with informational placards, passing through the existing 2 1/2 miles of trails with several types of woodland, forested wetland, and meadow habitats, which can support most Maine-endemic species;

- Local high school students’ science studies relating to our avian friends; students choose a bird species, learn about its habitat requirements, then design, build, and properly place nesting boxes in various areas in the Reserve.

But I was asked to talk about another facet of the Eco-Center and the Reserve: The Sanford Community Garden.

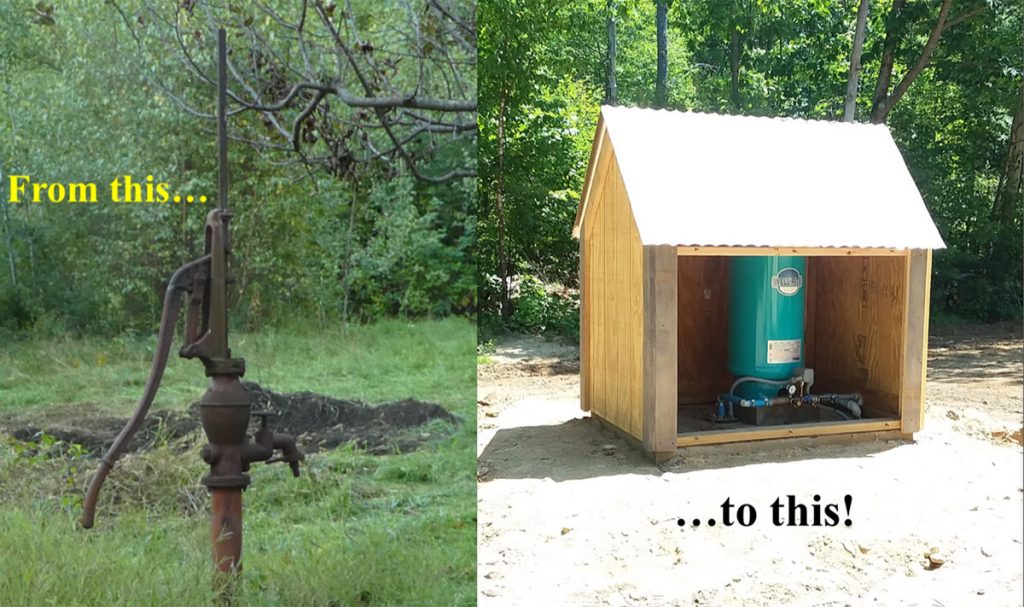

Public outreach and environmental awareness being leading tenets of Mousam Way Land Trust’s operational directives, the Reserve’s field next to a barn, and a windmill-styled hand water pump connected to a very productive drilled well both sparked a vision within the prescient-minded Dr. Bud Johnston, Trust co-founder and long-time President. “Let’s build a community garden, an offering sorely lacking in the Sanford area.”

Recruiting public involvement is always an agenda item when Trust projects begin, and this was no different. University of Maine Cooperative Extension Master Gardener Volunteers (MGV) from York County worked with Bud to plan, design, budget, source materials, solicit other volunteers, build, and maintain Sanford Community Garden.

It was very quickly realized that substantial financing would be required, so Dr. Bud got to work researching grant possibilities and doing the quiet and tedious work of grant writing. Generous donors, organizations, and local businesses answered Bud’s call for help; and the Maine Master Gardener Development Board answered mine!

With sufficient funding, it was shopping time. A neighbor’s recently rehabbed portable sawmill and his abundant hemlock trees became the planks that formed the 27, 4-foot by 12-foot raised beds. A neighboring town’s sawmill supplied the composted soil, which tested perfect for the garden’s use. Deer fencing, posts, tools, water supply materials, nuts, bolts, screws, landscape fabric … we had plenty of toys to play with! “Playtime” began with a friendly plumber removing the old hand pump and installing a pressurized system, using the electrical service available in the barn. Trenches were dug, lines and cable run, and garden hose manifolds designed, built, and installed. The annual United Way Day of Caring (UWDOC) organization found some energetic folks to work alongside some pre-enrolled raised bed gardeners and Trust members in Maine’s rocky soil, driving heavy steel fence posts and digging deep holes for the corner and gate posts, which were expertly fashioned by experienced carpenters that just happened to be among the UWDOC folks. Unbelievable, right!

While the posts and gates were being placed, Master Gardener Volunteers (you thought they just grew plants, right!?) joined others to assemble the heavy, 10-inch-high raised beds in neat rows, and line them all with landscape fabric. A helpful neighbor drove his tractor from his farm through some of the Reserve’s 2 1/2 miles of woods trails to help fill the beds with rich soil as they were built. Yet even more volunteers raked the soil level in the beds as some volunteers’ kids played in a huge, 1/8 acre “sandpit” — actually a foundation for the donated greenhouse yet to be installed — blessed again by generous donors, but that’s a story for another time.

Mishaps you ask? Learning as we go? Well…

- There was a time where the gravel delivery truck slid off the very slippery, waterlogged access road (remember the late, wet spring this year?), and “re-located” the neighbor’s (us!) raised bed of asparagus;

- The late Spring? Well, the soil at the vendors was too muddy to load into the trucks, so the delivery was delayed by about 3 weeks;

- Then, the roads were weight-limit posted, so the trucks couldn’t drive on ‘em ’til the postings got lifted!

- When the soil was sufficiently dried and the roads were open for the trucks, the dump trucks couldn’t make it all the way to the Community Garden area due to mud, so the soil got dumped in the neighbor’s (us, again!) driveway. (Notice the “s” on the word “trucks”? 55 yards in the driveway!)

Anyway, the raised beds are built, filled with soil, surrounded with an 8-foot-tall, high-tensile steel deer fence tightly stretched around steel and wooden posts, 5-foot-wide gates are swinging open for access, wood chips from the on-going city road building project are spread along the fencing perimeter and between beds, and hundreds of seed packets and rather sickly-looking plants donated from local businesses were placed in the hands of excited gardeners.

Well, the sickly plants survived MGV-rehab wonderfully and, along with hundreds of seeds now sprouting and plenty of watering hoses to keep them all happy, we are also growing a bustling community garden. Some beds are assigned to folks who have been granted waivers due to financial challenges (the Trust asks for a $25 donation to help cover operational and maintenance costs); some are being tended by supervised adults with disabilities; some are under the watchful eyes of a local school’s food-for-kids program; others are tended by Master Gardener Volunteers for local food pantries. A few have gone unassigned and are sprouting buckwheat cover crop sown to enrich the soil even further.

Next spring, we won’t be waiting for the soil to thaw and dry to allow trucking it to a waterlogged, impassable road (did I mention that we needed to rebuild and gravel a couple hundred feet of road to allow access to the garden area?). And with the water supply available, we expect gardeners to fill up all the beds and are anticipating a waiting list. The future is bright and bountiful!

Learn more about this project:

- Mousam Way Land Trust “Recent Activities”

- “Sanford Community Gardens receive grant”

- “Dig this: Community garden to bloom in Sanford”

- “Land trust endorses Springvale ecology center concept”

- “The Blanchard Project Part 1” (YouTube video)

- “The Blanchard Project Part 2” (YouTube video)

Food & Nutrition: Fall is for Food Safety

The University of Maine Cooperative Extension has countless food safety and food preservation resources. Please enjoy some of our seasonal favorites.

- How to Use and Preserve Cranberries (a UMaine Extension online video)

- #4191 Safe Home Made Cider

- #4262 Apples

- #4275 Let’s Preserve: Dried Herbs

- #4278 Barbecue and Tailgating Food Safety

- #4213 Food Safety Facts: Helpful Hints on Handling Turkeys for Thanksgiving

- How to Keep Food Safe After a Power Outage

Find more great resources on our publications, food preservation, and food safety websites.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications fill out our online form.

For more information or questions, contact Kate Garland at katherine.garland@maine.edu or 1.800.287.1485 (in Maine).

Visit our Archives to see past issues.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around Maine, with Katherine Garland, UMaine Extension Horticulturalist in Penobscot County, serving as editor.

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2019

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.

The University of Maine is an EEO/AA employer, and does not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, gender expression, national origin, citizenship status, age, disability, genetic information or veteran’s status in employment, education, and all other programs and activities. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies: Director of Equal Opportunity, 101 North Stevens Hall, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469-5754, 207.581.1226, TTY 711 (Maine Relay System).