Lesson 3. Fencing Systems — Appendix E

Farm Fences: Planning, Construction, and Cost

Ken Andries, Ph.D.

Livestock Specialist

University of Maine Cooperative Extension

Introduction

Fences have been used for livestock control for many centuries. Control of movement of domestic and wild animals has been their primary purpose. The location, type of animal, and its habits determine what type of fence works best.

The original fences were hedgerows or rock. Today we have many fencing options available to fit our specific situation. Materials range from vinyl to metal and wood. Wire can come in many forms including barbed, smooth, net and even chain-link.

Regardless of materials, construction of the fence determines how long and how well the fence will do its job. Proper construction evolves planning as well as material selection and the actual building of the fence.

Planning Process

We must start with a good plan to build a good fence. This is true weather building a permeate or temporary fence. Good planning includes making a map of the area, laying out the desired fence locations, and material selection.

The planning process starts by deciding where the fence will go, this means preparing a map of the area.

You will need information from three resources for the map: 1) soil type map, 2) aerial photograph, and 3) a topographical (topo) map of the location. Land capability or soil type maps show what soil types are in an area and what use and management practices are best for the land. Aerial photos show details of the present farm layout and give you an overall perspective of the land. Topo maps tell you the “lay of the land” or elevations and contours of your farm. These three pieces of information should be available from your local Farm Service Agency (FSA) or Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS).

The information is extremely important if you are working with a new place. However, it is just as useful on property you have owned or farmed for years.

Once you have the information, map out boundaries of hay, crop, pasture, and all other use areas for the property. This defines the boundaries you will be work with. Use the soil and topo maps to avoid problem areas such as wet locations as much as possible. Fence out ponds and low wetland areas that hold water on regular bases to improve herd health and maintain a clean water supply for the animals.

You should review the plan and if possible view the location of the new fences. Where drainage ditches or ponds added since the last aerial photo, do you need to clear a lane through a wood lot, are old fences present that were not on the map or photo? These are all things that you will need to adjust for in your plan.

With the map complete, you should be ready to determine the size of your pasture. Plot the new fences and plan for gate locations, allies/lanes, and other features you will need to move and work cattle. Then measure the length and plan for corner post, gate post, and in line bracing or pull post. This will allow you to make an accurate list of material you will need for the project.

Lanes are very useful in moving livestock from one pasture to another or for moving to a central working facility. Gates should be located in corners for ease of moving livestock and across from each other along lanes.

Types of Fences

There are two basic types of fences, permanent and temporary. Permanent fences are designed and constructed to last a long time, generally 20 to 40 years, while temporary fences are used for a short time, usually a few months. The material and construction methods differ with each type. Permanent fences are made with sturdier post and constructed to provide long service with minimal maintenance. Temporary fences are generally used for rotational or seasonal grazing, to keep livestock away from hay stacked or cut in a pasture, or to provide a “quick fix” for a permanent fence to be repaired later.

Permanent fences are used around the perimeter of your property as well as major dividing fences or cross fences in pastures. They are constructed with metal and/or wood post in general and define the basic shape of your pasture.

Temporary fences are not as well constructed and generally have fewer strands of wire, greater distance between post, and generally will only last 3 months to a year. They are used in intensive grazing operations, to separate animals from hay or winter forage. Or to reestablish parts of a pasture. They can also be used to provide a “quick fix” for downed permanent fences to be repaired later.

In the planning stage you will need to plan for both types of fences as they fit your operation. All perimeter fences need to build as permanent fences. Also any cross fences should be permanent as well as those around ponds. Temporary fences can be added at a later date and or moved as needed. However if you plan to use temporary fences a sturdy post in key locations along the permanent fence can be very helpful. Also the type of permanent fence may be selected to aid in adding the temporary fences later.

Material Selection

Now that the fence is planned and you have the measurements, its time to select the materials. Fencing materials commonly used include boards, barbed wire, woven wire, cable, mesh wire and high tensile wire. Electricity can be added to most fence types to increase effectiveness. Post materials include wood, metal, plastic, fiberglass, and composite materials. The purpose of the fence will determine the most appropriate material for your situation.

Fencing materials

Board and chain link fences are very nice and if maintained properly they will work for may years. However, their cost makes them impractical for most operations. These materials would be good choices however, for around farm buildings, yards, or gardens. They can improve or enhance the appearance of a home or farm yard.

Cable or pipe is another good fence material for specific applications. These materials work very well when used for holding pens or dry lot operations. Cable and pipe are both very strong fences. Cables allow for some give to the fence while pipe is very ridged. Again the cost of these types of fences are prohibitive for most applications.

Barbed wire is probably the most common type of wire used today. The typical barbed wire fence will have 3 to 6 strands of wire and is used for cattle, horse or large exotics. This type of fence is not well suited for control of smaller animals or for wildlife control. Barbed wire is generally sold in roles of 80 rods (80 rods = 1320 ft. = 1/4 mile) in length and is available in several stiles and sizes. A standard barbed wire fence has 5 to 6 post per 100 ft and may have wire stays between the post.

High-tensile fences are growing in popularity and can be used in place of barbed wire. These fences are made of smooth wire and generally have 5 to 10 strands. The wire is screeched between pull post with tension being maintained by springs in the fence. There are also ratch devices placed in the run to allow you to adjust tension if needed. The advantages are that it is somewhat easier to handle, easier on livestock, and easy to adapt. It is also generally more economical than other fences and has a longer life expectancy. High tensile fences work well for large livestock and can be adapted better than barbed wire

Woven or net wire, also know as hog wire, fences are the last type we will discuss. These fences are best suited for small animals such as sheep, goats, or hogs. It is also the best for controlling some types of wildlife. The wire is a series of horizontal wires held apart by vertical stays. The square or rectangle gaps in the wire generally get smaller towards the bottom of the fence. The wire generally comes in 26 to 48 inch heights. This wire is generally more expensive than barbed wire fence. In many applications a single strand of barbed wire is placed above the net wire to help keep animals from jumping or to keep large animals from reaching over the top. A barbed wire at the bottom of the fence will do the same to discourage going under the net wire.

Electric fencing

Electric fences are becoming more popular due their effectiveness and ease of making quality temporary fences. Electricity can be added to any fence with a little modification. Electric fences are very effective because they provide a physical and physiological barrier.

Electric fences can be temporary or permanent. Permanent electric fences generally utilize high tensile fencing materials and are either a fence them selves or a single wire added to an existing permanent fence. Temporary electric fences can then be made as extensions off the permanent fence.

The addition of insulator is all it generally takes to make the conversion from a regular to an electric fence. Offset stays are used to add an electric wire to existing conventional fences. In a new application in high tensile fences, every other wire or each wire can be “hot.”

T o make an electric fence effective you need a good fence charger. The setup of the changer is also important. A charger that is not well grounded will not be effective. You also need to follow recommendations for lightning protection provided by the manufacture. Poor instillation or lack of maintenance can make electric fences very dangerous. Home made chargers and improper instillation can result in serous injury or death.

The fence needs to be grounded to work. Most permanent fence application have every other wire hot. The other wire acts as a ground. In single wire applications the moisture in the ground allows for completion of the circuit and improves effectiveness of the fence.

When selecting a charger, be sure to consider current and future plans. Chargers are designed for a specific length of fence. If you exceed that length you reduce the effectiveness of the fence and in some cases can render the fence useless. Additions of cut-off switches and spring gaps also improve your ability to work on a fence if problems occur. Again planning is important to decide the best strategies for your situation.

Post Selection

Fence posts are a very fundamental part of a fence and proper selection and installation will determine the life of the fence. There are three basic materials used for posts: wood, metal, and fiberglass. Plastic and some other recycled or composite materials are also being used but are not common in most areas.

When selecting post materials, we need to look at ease of installation, longevity, and availability. The type of the fence, permanent or temporary, will also play a role.

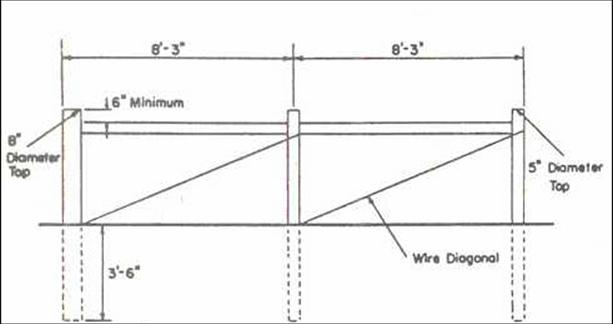

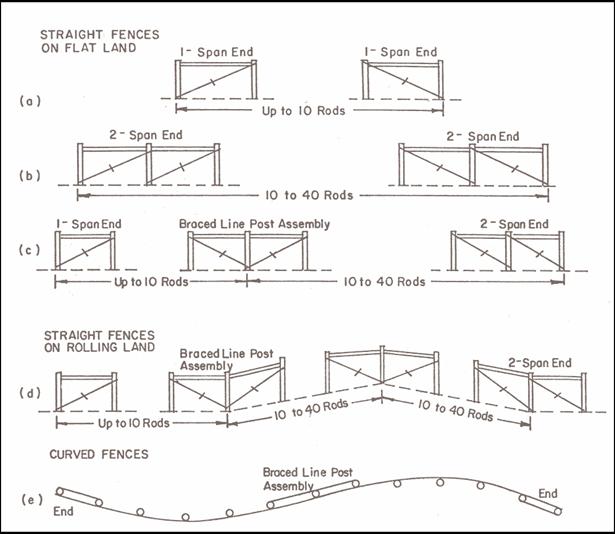

Corner post, gatepost and all pull post/brace assembly need to be very sturdy to hold the tension in the wire and/or weight of a gate. You should have a brace assembly or corner post with brace every 650 feet or less along a fence to insure good tension on the wire. Wooden posts for these uses should have a top diameter of 8 inches. Metal posts should be 3 to 4 inches minimum with a concrete anchor 20 square inches and 3 ½ feet deep to insure it holds.

Line posts should be placed every 12 to 20 feet for wooden posts over 3 ½ inches in diameter or 12 to 15 feet for metal t-posts or wooden posts under 3 ½ inches in top diameter.

Fiberglass posts can be used in the place of metal or wooden post on the 15 or less spacing. These posts give some flexibility and are very useful for electric fences. Composite and recycle material posts can be use similar to wood or t-posts depending on their size and manufacture’s recommendations.

When selecting wooden posts consider the type of wood as well as wood treatment. Treatment can double or even triple the life expectancy of a wooden posts. Black locust and cedar make very good posts. Many other hardwoods also have a long life expectancy if pressure treated. Softer woods are more subject to rot as is hickory and red oaks.

Metal posts have replaced wood posts in most areas due to their ease of handling. Metal posts are driven in to the ground and wire is attached by clips. Small wood posts can also be driven but larger ones require digging post holes for proper placement.

Composite and plastic posts can be used in place of other types depending on material and construction. These materials are generally used for temporary fences and electric fences.

A final note about fence posts. A living tree should never be used as a fence post. As the tree grows the wire becomes imbedded in the wood. This causes pressure on the wire and increases the degeneration rate of the wire. This combines to increase wire breakage. It also decreases the future value of the timer. If necessary, cut trees along the planed fence line and kill the stumps. Keep trees and other weeds from growing up around the fence to increase its useful life.

Fence Construction

Corner and Brace Assembly

One of the major challenges in fence construction is keeping the wire taught over the years. This is the job of the brace and corner assemblies. These groups of posts must be designed to take the pressure and strain of keeping the wire tight and holding gates over the years without moving. Proper construction and placement will increase the life of the fence while reducing maintenance.

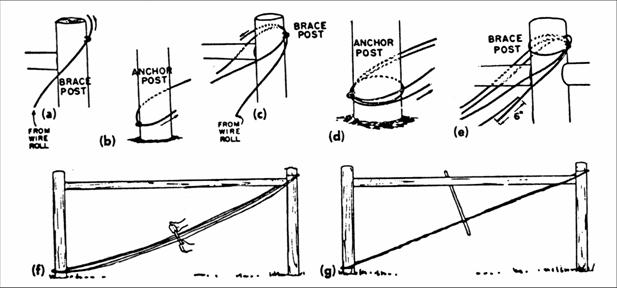

Corner post and brace post assemblies consist of two to three large diameter posts (top diameter 8 in or grater) and need to be supported with a cross post and tied together with a diagonal wire loop. This loop should go from the top of the post in the direction the pull is coming from and the bottom of the support post (middle in a three post design). This allows the post to transfer the force being placed at on its top to the ground level of the support post anchoring it in place. See the figures for more information on design and placement of brace assembles.

Conclusions

Proper fence construction will result in many advantages. The fences will last longer and be more effective if planned and constructed properly. There are many products available for use in fence construction. This makes the planning process more important because they are not all effective for all types of animals and in all situations.

The building process should always start with a plan. The plan needs to include current and predicted future needs. Take into consideration the lay of the land and current boundaries. Be sure to clear a path for the fence through woods and thickets. This will help in building a strong fence and increase its life.

Electric fences are very good for keeping livestock confined. They can also increases the life of existing fences. However, be careful and select only quality products and have them tested regularly to be sure they are safe.

Finally, remember that a well constructed fence is no guarantee that livestock will not get out. Proper maintenance and checking for problems is very important to reduce your chances of liability. The better the fence is constructed and the better maintained, the better for you. Parameter fences are the major concern in these types of situations. For cattle they should be five strands of barbed wire or net wire. Electric fences are also helpful but pose their own problems. Check with the local district attorney’s office for information on local regulations related to fences and livestock confinement.

Literature Cited

- Kay, Furman W. Fences for the Farm. University of Georgia Cooperative Extension Service Circular 774, 1985.

- Turner, L.W., C.W. Absher, and J.K. Evans. Planning Fencing Systems for Intensive Grazing Management. University of Kentucky, Cooperative Emersion Service ID-74, 1986.

- Watson, Harold. Electric Fences. Southern Regional Beef Cow-Calf Handbook. SR7002, 1977.

- Watson, Harold. Wire Fences. Southern Regional Beef Cow-Calf Handbook SR7004, 1978.