Eliminating Chronic Disease Using a Farmbased Approach: Caseous Lymphadenitis (CL)

SARE Farmer Grant Final Report 2014

By Anne Lichtenwalner DVM Ph.D., University of Maine Cooperative Extension, and Animal and Veterinary Sciences

CL: What is it?

- “Cheesy gland”: Chronic bacterial infection Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis

- Stays in the immune system

- May cause skin or internal abscesses

- Can be spread from animal to animal:

- Must have skin penetration

-

The location of lymph nodes on a goat. Persistent in the environment

- Use antibody response to test for the presence of bacteria in unvaccinated animals

- Vaccines are available; not highly effective

Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis: lymph nodes

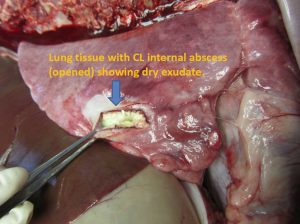

- External: Firm, dry abscesses- slow to develop

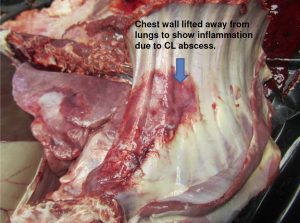

- Internal: Weight loss, coughing

CL: Internal abscesses (goat at necropsy)

CL: How contagious is it?

Transmissibility

- Direct inoculation of bacteria into new host

- Cut or ulcer, contact with exudate

- Bites from flies that have contacted exudate

- Rubbing on a tree, etc. that has exudate on it

- Inhalation of infected secretions

- Sheep with bronchial lymph node abscesses: coughing

- Milk?

- If mammary lymph infections present

- See more recent info (below)

Treatment

- Vaccines or antitoxins:

- Don’t prevent or cure, but may decrease abscesses

- Immune clearance ineffective

- Toxins overcome normal immune defenses

- “Hides out” inside cells

- Uptaken by macrophages; survives and is spread to lymph nodes

- Antibiotics

- In vitro, many are effective

- In vivo, nothing works: food animal limitations re antibiotics

- Rifampin with tetracycline was useful in early infection

Sources:

Judson et al, 1991. Veterinary Microbiology 27(2): 145-150.

Senturk and Temizel, 2006. Veterinary Record 159(7): 216-217

CL: How long does it last on my farm?

Non-spore former, but environmentally stable

- C. pseudotuberculosis wasn’t killed by 4 months in soil samples containing exudate from CL abscesses, and after 11 months in sterilized soil samples (40º F, 72º F, 98 º F and ambient conditions).

- C. pseudotuberculosis was killed after 3 hours in chlorinated tap water but could survive up to 70 hours in distilled water.

- Disinfectants: many are effective against CL after a thorough cleaning of surfaces. However: rough surfaces such as wood may be impossible to disinfect.

CL: Can I detect or prevent it?

CL: Can I detect or prevent it?

Detection

- Exposed animals: PLD antibodies

- Test-based on detecting antibodies

- “Seropositives” carry the bacteria

Prevention

- Vaccines not 100% effective

- Boosters, accurate records needed

- Vaccine will NOT cure, only help prevent abscesses

- Using vaccine creates “seropositives”

- Testing and culling seropositives: best method

- But will this work for all farms?

Trial Methods

SARE Grant: CL in Sheep

- Visit farm: use farm vet if possible

- Test sheep: 0 and at least 60 days

- Initial SHI tests were done by Washington State University

- Report results (farm ID confidential)

- Consultation

- Biosecurity

- Tailor methods to farm type

- Survey

- SHI test method developed at UMaine lab in Orono

- Supports local industry

- Create easier access to vigilance methods

- Validate CL-free status for producers

Farm types tested

- Breeds: Many

- Products: Fiber, meat, milk

- Biosecurity: Varied greatly

CL status

- 8 of 17 had positive animals at first test (47%)

- 22% of 705 sheep tested at least once were CL+

- 8 of 9 negative farms stayed negative (1 didn’t retest). Closed herd and good biosecurity essential

- Inability to run test locally interfered with outcome

- At follow-up, most of the positive farms had culled or isolated positive animals

Biosecurity: example (Farm 2)

- Breeding for fiber and meat: Animals may travel off farm: limited or no quarantine

- Tested “home” animals: all neg.

- Tested “returned” animals: 1 pos.

- Retested “home” animals: new positive

Followup: culled all positives, implemented quarantine procedures for returning animals

Trial Results

Farmer compliance

- All farmers directly contacted said they would cull

- Follow-through really varied. “Favorites” or great producers were unlikely to be culled.

- Most were unwilling to replace wooden feeders or other areas where CL transmission likely.

- Most thought their biosecurity was excellent

- All were highly concerned and involved in the success of their flocks

- Some of the 17 farms had camelids; none had goats

Farmers resented “buying” chronic disease

- “Do unto others” was a strong motive

Conclusions

- Prevalence higher than expected

- Does being CL-free add to value?

- “Caveat emptor”: Selling CL free breeding stock=value

- Other species affected: goats, camelids

- Be careful of guard animals: need testing, too

- Farm type dictates whether vaccination ok

- Reluctance to cull is common

- Vaccination takes away possibility of testing

- No strategy works longterm without culling

- Biosecurity and determination dictate whether disease-free status is achievable

Outcomes

- Awareness of CL increased

- Added value of CL-free status

- Biosecurity templates in development

- Google Earth model may help communications about farm layout and biosecurity

- SHI method now in Orono on a research basis

- Project continuing studying goat dairies in 2014-5

- Sheep testing available in 2015 if serum samples can be collected/shipped to UMAHL (no charge for testing)

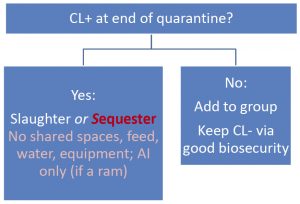

- Decision Tree: Start by knowing your status

- Assess the cost of CL-free status for your farm

- May not work for everyone

Outcomes: Recommendations

- Know the CL status of your flock: retest as needed

- Maintain closed flock/herd with high biosecurity

- Notify visitors about biosecurity

- Inform shearers about biosecurity

- New or returning animals:

- Don’t immediately mix with “home” flock

- “nose to nose H quaranIne”

- CL test immediately at entry and prior to release from quarantine (2 mo. later)

- If positive, cull or sequester positives

- Don’t immediately mix with “home” flock

» Retest exposed animals at 2 months: cull if +

» Keep quarantined until all negative for CL at 2 consecutive tests 2 months apart

Outcomes: Decision Tree

Outcomes: Decision Tree

Impacts

- Stopped CL on several farms

- Estimated 20% improvement in fiber yields

- Potentially reduced carcass condemnation

- Outreach to SR vets

- Free testing may enhance communications

- Help establish VCPR with farmers

- Farmer-to-farmer:

- Added value of CL-free stock

- Building biosecurity awareness

- Students

- projects and experience

Recent Undergrad Student Theses on SR

- Edith Kershner: Case study of sheep farms with or without CL.

- Abigail Royer: Detecting CL using complete blood counts.

- Amy Fish: Evaluating macrophage responses to CL.

- Rachel Chase: Evaluating neutrophil responses to CL.

- Cassandra Karcs: CL prevention in small ruminants.

- Hallie Lipinski: CL and its connection to milk.

- Anna Desmarais: Selenium and footrot prevalence.

- Alden West: Composting effects on coccidia.

- Alexandra Settele: Anthelmintic resistance in H. contortus

- Amanda Chaney: Identification of internal parasites of sheep and goats

- Caitlin Minutolo: Effect of age on susceptibility to ovine footrot.

- Nicole Maher: CL webinar for producers

- Casey Athanas: Pedigree analysis to help eradicate footrot.

- Katrina Glaude: Should sheep with footrot be culled?

- Kayla Porcelli: Biosecurity survey for footrot positive farms

- Marie Smith: Pasture management to control parasites in small ruminants.

References

- Sheep and Goat, Wool and Mohair: 1982. Research reports, Texas A and M University.

- Augustine JL and Renshaw HW. Longevity of C. pseudotuberculosis in six Texas soils. P 102

- Augustine JL, Richards AB, Renshaw HW. Persistence of C. pseudotuberculosis in water from various sources. P 104.

- Assis RA, Lobato FCF, Martins NE, et al. Clostridial myonecrosis in sheep after caseous lymphadenitis vaccination. The Veterinary Record 2004;154:380-380.

- Paton MW, Walker SB, Rose IR, et al. Prevalence of caseous lymphadenitis and usage of caseous lymphadenitis vaccines in sheep flocks. Australian Veterinary Journal 2003;81:91-95.

- Fontaine MC, Baird G, Connor KM, et al. Vaccination confers significant protection of sheep against infection with a virulent United Kingdom strain of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. Vaccine 2006;24:5986-5996.

- Baird GJ, Malone FE. Control of caseous lymphadenitis in six sheep flocks using clinical examination and regular ELISA testing. The Veterinary Record 2010;166:358- 362.

- Washburn KE, Bissett WT, Fajt VR, et al. Comparison of three treatment regimens for sheep and goats with caseous lymphadenitis. Journal Of The American Veterinary Medical Association 2009;234:1162-1166.

Acknowledgements

- Collaborating Farmers of Maine

- Collaborating Veterinarians:

- Drs. Becky Myers Law and colleagues

- Dr. Tammy Doughty

- Dr. Don McLean

- Dr. Beth McEvoy

- NE SARE: Carol Delaney

- Extension colleagues: Richard Brzozowski and Donna Coffin

- Technical/lab assistance:

- Edith Kershner, Anne Ryan, Hallie Lipinski, Abbie Royer

- Ann Bryant

- University of Maine Cooperative Extension

- University of Maine School of Food and Agriculture