Cranberries and a Changing Climate

This is the web/text version of a Powerpoint presentation given at the University of Maine in Orono by Charles Armstrong, UMaine Extension’s Cranberry Professional, in 2016.

Slide 1 (Title Slide): “Cranberries and a Changing Climate” by Charles Armstrong, Cranberry Professional, University of Maine Cooperative Extension – 2016

Slide 2: Family Ericaceae [heather/heath family]

Genus Vaccinium: examples include cranberry, blueberry, lingonberry, bilberry (whortleberry), cowberry, and huckleberry; the Vaccinium genus contains about 450 species in total, which are found mostly in the cooler areas of the Northern Hemisphere.

Slide 3: What do cranberries like/need? Indigenous to the Temperate Zone (Vaccinium macrocarpon – native only to North America); acidic pH (4.0 to 5.5); full sun (generally the more sun, the better); optimum growth occurs from 60°F to 80°F; cool temperatures when fruit are maturing (as temperature goes down, anthocyanin production goes up); access to abundant water (‘boggy’/peat habitats); cold winters (to satisfy the plant’s chilling requirement)

Slide 4: Winter ‘resting’ period (chilling requirement) Cranberry plants have what is called a “chilling requirement.” Abnormal blossoming has been observed to take place in Massachusetts when plants received less than 1500 hours (~62 days) below 45°F during the winter. This resulted in abnormal blossoming called “Umbrella Bloom” in which the stem above the flowers does not grow or does not grow very much. There is also some evidence to suggest that the chilling hours may be lost during ‘ups and downs’ of temperatures that often occur in the Northeast in December and January, such that chilling hours may have to start accumulating all over again.

Slide 5 (Photo): Photo showing the physiological condition in cranberry called “Umbrella Bloom” where the normal 1″ to 2″ of stem growth above the flowers is greatly reduced or entirely absent.

Slide 5 (Photo): Photo showing the physiological condition in cranberry called “Umbrella Bloom” where the normal 1″ to 2″ of stem growth above the flowers is greatly reduced or entirely absent.

Slide 6: Without the 1” to 2” of stem growth (with accompanying leaves), there is very little photosynthetic carbon available to the upright; thus, usually no more than just onecranberry per stem is obtained on those stems, when otherwise two or more berries per stem would be possible. Potentially a 50% yield reduction if going from 2 berries per stem to only 1 berry per stem.

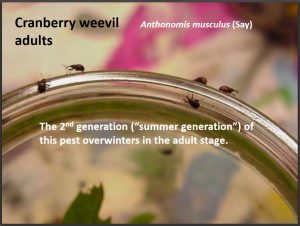

Slide 7: Cranberry [Insect] Pests: How do they overwinter? Egg stage (least vulnerable to cold) [cold temperatures & cold duration]: Blackheaded fireworm, Chainspotted gemeter, Redheaded flea beetle, Cranberry blossomworm, Gypsy moth, Blunt-nosed leafhopper and Green spanworm; Pupal or Larval stages (a bit more vulnerable to cold): Cranberry tipworm (pupa), Cranberry fruitworm (larva), Brown spanworm (pupa), Big cranberry spanworm (pupa); Adult stage (even more vulnerable to cold): False armyworm (moths), Cranberry weevils, and Winter moth — Climate change projections of milder and shorter winters for the northeast should aid in the survival of these three pests!

Slides 8 and 9: Climate Projections for the Northeast — Figures taken from a report by the USDOT’s Federal Highway Administration (using data from USGCRP): https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/climate_change/adaptation/publications/climate_effects/

- Temperature:

- Near-term (2010-2040): ~2.5°F rise in the annual average temperature; Slightly higher than 2°F rise in the spring and summer average; ~3.0°F to possibly 3.4°F rise in winter’s average temperature

- Mid-century (2040-2070): Between 3.8°F and 4.8°F rise in the annual average temperature; Similar rise (3.8°F to 4.8°F) for summer & fall; 3.5 to 4.1°F for spring; 4.0°F to 5.4°F rise in winter’s average temperature

- End-of -century (2070-2100): Between 5.4°F and 9.0°F rise in the annual average temperature (similar rise for winter, summer, and fall) (range of 4.2 to 10.8°F); 5.0°F to 8.1°F rise in the spring average temperature; Shorter winters (snow season cut in half in Maine!)

- Rise in number of “extreme heat days”:

- Near-term (2010-2040): Boston: 4 to 8 more days per year above 90°F

- Mid-century (2040-2070): Boston: 12 to 29 more days per year above 90°F

- End-of -century (2070-2100): Many US Northeast cities ~13 to 63 more days reaching 90°F compared to years 2010-2016

Slide 10 (heading slide): Likely Consequences

Slide 11: Higher Temperatures; Likely Consequences: Warmer/earlier springs: Buds swelling sooner/faster (sensitive to frost sooner than growers are accustomed to), and potentially more nights needing to protect from frost.

Slide 12: Higher Temperatures; Likely Consequences: If warmer in late summer: Berry scalding – when berries are injured from the heat (already poses a challenge in NJ and MA), and poorer berry color resulting in less nutritious fruit (less anthocyanin) and reduced marketability.

Slide 13: Higher Temperatures; Likely Consequences: Hotter summers: Heat stress/injury to vines/flowers (especially when 90°F +), and more days of “too hot for bees” (i.e. potentially fewer honeybees out pollinating!)

Slide 14: Bee Protection: Hotter summers will put added stress on the bees, so it will be more important than ever to consider bee toxicity when a pesticide is applied during any period when bees could be exposed. The list of products for cranberries is sure to look different in the future, but this is how it looks as of 2016 for “Relative Risk Quotient” which is the ‘use rate’ of the product divided by its toxicity (the Relative Risk Quotient is shown in parentheses after each product name):

- Greatest Relative Risk (Highly Toxic): Admire® (135), Success® (50), Lorsban® (25), Diazinon® (22), and Actara® (16)

- Moderate Relative Risk: Delegate® (much more toxic when it’s wet) (1.2), Assail® (0.01) and Avaunt® (0.01)

- Lowest Relative Risk: Intrepid® (0.002), Rimon® (0.00078), and Altacor® (0.00095)

Slide 15: Higher Temperatures; Likely Consequences: Shorter and milder winters: Chilling requirement more and more difficult to satisfy, giving rise possibly to more and more “umbrella bloom”; Better survival of insect pests, especially false armyworms, cranberry weevils, and winter moths . . . but all the insect pests would stand to benefit. Greater risk of lower yields!

Slide 16: Higher Temperatures; Likely Consequences: more False armyworm, more Cranberry weevil, more Winter moth

Of all our cranberry pests, we should review or familiarize ourselves with the first two pests in particular since these two are already increasing in occurrence and have been a consistent problem on Maine cranberry beds yearly. Winter moth has yet to be discovered on any of our cranberries [in Maine] but that could change if it continues to spread to more towns and regions of the state; it ‘is’ a large problem on Massachusetts cranberry bogs.

Slide 17 (Photo): Photo of a pair of False Armyworm caterpillars next to a US dime for scale purposes.

Slide 17 (Photo): Photo of a pair of False Armyworm caterpillars next to a US dime for scale purposes.

Slide 18: So what’s so bad about False Armyworm?

Life Cycle: There is a single generation per year. The moths which have overwintered mate in the early spring. Each female moth can lay roughly 600 eggs in masses of sometimes 100 or more that they place on the cranberry stems or the undersides of the leaves in late April through early May. The eggs hatch typically in mid to late May. The caterpillars mature at the end of June, then move to the ground where they ‘rest’ for two to six weeks before pupating. The moths emerge from mid to late August through the end of September, and seek out protective places to spend the winter.

Slide 19: So what’s so bad about False Armyworm?

Cranberry Injury: Early Season (late May through early June): The caterpillars are the damaging stage, and when they are young, they can do great damage by chewing out the centers of the terminal buds before the new growth begins. Summer: The caterpillars grow hand in hand with the cranberry growth, eating more and more as they increase in size and feed on leaves, buds, and flowers, eventually reaching 1.5-2” in length at maturity. Upon reaching their larger size of 1” or more, they will begin to feed primarily if not exclusively at night in order to avoid being seen by predators.

Slide 20: False Armyworm Management:

- Sweeping: Sweep for the young larvae with a 12”-diameter sweep net starting around May 23rd in Maine; preferably earlier in warmer parts of the state. Action Threshold is 4.5 to 7 larvae per 25 sweeps, depending on cranberry fruit price and individual comfort level; traditional threshold is 4.5; Early detection is important!

- The ‘Late Water’ Flood is very effective!: This flood, applied starting around April 21st – April 26th, controls False armyworm, at least in Massachusetts if not also in Maine. It is a 30-day spring reflood applied several weeks after the winter flood has been removed and before the plants have fully lost their dormancy color.

- Spray Choices (as of 2016): Altacor®, Confirm®, Intrepid®, Diazinon®, Lorsban®, Hatchet®, Orthene®, Sevin®, Delegate®, Avaunt®, Bt and Entrust®

- Much more information about this pest may be found in UMass’s Cranberry Insects of the Northeast book: http://www.umass.edu/cranberry/downloads/Cranberry%20Insects%20of%20the%20NorthEast.Averill.Sylvia.Franklin.2000.pdf

Slide 21 (Photo): Photo of five cranberry weevils crawling along the edge of a small glass jar (a baby food jar), with text that says: Cranberry weevil adults, Anthonomus musculus (Say); The 2nd generation (“summer generation”) of this pest overwinters in the adult stage.

Slide 21 (Photo): Photo of five cranberry weevils crawling along the edge of a small glass jar (a baby food jar), with text that says: Cranberry weevil adults, Anthonomus musculus (Say); The 2nd generation (“summer generation”) of this pest overwinters in the adult stage.

Slide 22: So what’s so bad about Cranberry weevils?

Cranberry Injury — Springtime: Weevils which have overwintered begin to move onto the beds from the surrounding uplands and will drill holes into old leaves and in the terminal buds. Mid-June through early July: The weevils mate, and move to the new cranberry growth, especially new terminal growth and new buds which can be damaged severely from their feeding holes. Flower buds that are damaged often fail to open, dry up, and then eventually fall to the ground. Eggs are deposited into the unopened blossom buds, where the subsequent weevil larvae develop. Females will chew on the pedicels after depositing their eggs, either severing them completely, or only partially, creating a point of weakness that often leads to the pedicel breaking off later on. Buds that remain attached but contain a larva turn from pink to a brownish-orange. In short, a heavy infestation can destroy much of the prospective crop due to blossom bud losses, and the brand new weevils emerging from them may also damage any berries that are present.

Slide 23: Cranberry Weevil Management:

- Sweeping: Sweep for the adults with a 12”-diameter sweep net during warm, sunny parts of the day (~noon to 2 pm) when they are most active; During cold, wet or windy weather, they stay inactive on the bed floor; Experts at ‘playing dead’ so care must be taken not to overlook them; Action Threshold is 4.5 weevils per 25 sweeps in the spring; 9 weevils per 25 sweeps in the summer (‘summer’ weevils are more robust, so harder to kill).

- Flooding is not effective!: Cranberry weevil populations are not reduced noticeably by a winter flood or a ‘Late Water’ flood, presumably because the weevils are not present on the bed(s) during those periods.

- Spray Choices (as of 2016): Lorsban®, Avaunt® (Registered for spring populations only—so no summer applications), Hatchet®, Actara®, Scorpion®, Venom®, Belay® (summer applications only, i.e. post-bloom; very high bee toxicity)

- Much more information about this pest may be found in UMass’s Cranberry Insects of the Northeast book: http://www.umass.edu/cranberry/downloads/Cranberry%20Insects%20of%20the%20NorthEast.Averill.Sylvia.Franklin.2000.pdf

Slide 24: Climate Projections for the Northeast — Figures taken from a report by the USDOT’s Federal Highway Administration (using data from USGCRP): https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/climate_change/adaptation/publications/climate_effects/

- Precipitation:

- Near-term (2010-2040): Summer precip projected to increase by 2% (range of -1 to +6%); Single precip events likely to increase in intensity by ~7%

- Mid-century (2040-2070) (with “business as usual” scenario): Summer precip up only 1 to 2% (least increase vs other seasons), but…. more than 8% rise in avg. amount of rain falling on any given day, and an 8-13% rise in amount during any 5-day period.

- End-of-century (2070-2100) (with “business as usual” scenario): Greatest precip increase will be during the winter (11-17%) (range of 4-27%) and increasingly in the form of rain versus snow. Snow season for most of the Northeast reduced by 25 to 50%! Summer still the least affected of the seasons (just 2% rise in precip), but the intensity of any particular precip event likely to increase by 12-13% on average.

Slide 25 (heading slide): Likely Consequences

Slide 26: Rise in precipitation and/or its intensity (likely consequences):

- Winter (more rain vs snow): harder to keep layer of ice intact for protecting the plants;

- Summer: A 2% rise in precipitation would likely have little impact to the crop, overall. But getting less than 3.2” of total rainfall during June awards 1 point to the ‘Keeping Quality Forecast Model’ (out of 16 total points in the model) (fruit rot fungi thrive in warm and wet conditions); But, greater intensity? And its timing?: If a lot of rain falls during bloom, that could be very harmful:

- Fruit rot infection occurs during bloom

- Flowers knocked off (hard rain or hail)

- Pollen washed away (less attractive to bees after)

- Bees don’t work in moderate to heavy rain

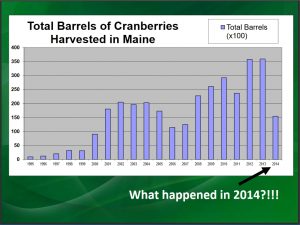

Slide 27: (Photo): Photo showing total barrels of cranberries harvested in Maine between 1995 and 2014, with a large drop in 2014 of more than half, with a question posed on the slide that asks: “What happened in 2014?” (the total dropped from 35,870 barrels in 2013 down to 15,428 barrels in 2014).

Slide 27: (Photo): Photo showing total barrels of cranberries harvested in Maine between 1995 and 2014, with a large drop in 2014 of more than half, with a question posed on the slide that asks: “What happened in 2014?” (the total dropped from 35,870 barrels in 2013 down to 15,428 barrels in 2014).

Slide 28 (suggests an answer to the question posed in slide 27): Answer: Too much rain during bloom!!! Bangor had 6.8” of rain in July of 2014 (close to the record 7.25” in 1983) and 3.43” fell in just 24 hours from July 4th-5th when the plants were as much as 40% in bloom.

Slide 29: Summary (Likely Consequences):

- Increasing Temperature:

- Higher insect pest populations (especially false armyworms and cranberry weevils)

- Chilling requirement hard to obtain

- Poor berry color (less nutritious; less marketable)

- Loss of frost hardiness (more frost protection needed)

- Heat stress and berry scald (crop injury)

- Poor pollination (too hot for bees)

- Increasing Precipitation:

- Poor pollination / poor flower viability (if it occurs during bloom period)

- Higher fruit rot pressure and infection rates

Slide 30: Further Study: Check out Cornell’s Northeast Regional Climate Center at: http://www.nrcc.cornell.edu/ Also, consider viewing the USDA report entitled: “Adaptation Resources for Agriculture: Responding to Climate Variability and Change in the Midwest and Northeast.” It is meant to help producers prepare for, cope with, and recover from extreme weather and uncertain climate conditions and may be found online at: http://www.climatehubs.oce.usda.gov/sites/default/files/adaptation_resources_workbook_ne_mw.pdf?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery

University of Maine Cooperative Extension Pest Management Unit

17 Godfrey Drive Orono, ME 04473

207.581.3880 • charles.armstrong@maine.edu

https://extension.umaine.edu/ipm/

The University of Maine is an equal opportunity/affirmative action institution

Accompanying Questions to the Online Workshop: “Cranberries and a Changing Climate”

by Charles Armstrong, Cranberry Professional / University of Maine Cooperative Extension

Instructions: You can email the information being asked on this form, as well as your quiz answers (or photos of the completed papers) to Charles Armstrong at charles.armstrong@maine.edu or, alternatively, you can print out this completed page and your quiz answers, and mail to the Umaine Extension Diagnostic and Research Laboratory, c/o Charles Armstrong, 17 Godfrey Drive, Orono, ME 04473.

License Information: (check all that apply and enter your license number if available)

- Private License – Lic. #_______________

- Restricted Dealer – Lic. #______________

- Commercial Operator – Lic. #__________

- Commercial Master – Lic. #____________

Applicator Information:

NAME: (last)_____________________ _(first)____________ Jr./Sr./III etc _________

Company/Agency/Farm: ___________________________________________________

Mailing Address:

(Street)__________________ (City)____________ (State)_____ (Zip)_________

Under penalty of law, by signing below I certify that I am the true and actual license holder named above. I understand that under no circumstances shall anyone but the above named individual sign below.

Signature: __________________________________________ Date: ___________

Quiz Questions:

- Cranberry plants in the northeastern US that have experienced less than 1500 hours during the winter months below 45°F would be expected to have which of the following conditions:

- A) False Blossom Disease

- B) Red Leaf Spot

- C) Umbrella Bloom

- D) Upright Dieback

- When the ‘chilling requirement’ of cranberries during the winter has not been achieved, one has the ‘potential’ to suffer a yield reduction that season of as much as:

- A) 10% to 25%

- B) 25% to 33%

- C) 33% to 50%

- D) 50% or more

- Which of these overwintering insect life stages is generally the least vulnerable to cold temperatures and/or the duration of cold temperatures?

- A) Egg stage

- B) Larval stage

- C) Pupal stage

- D) Adult stage

- True or False: All species of spanworm in the US northeast overwinter as eggs.

- Which of these cranberry pests in the northeast should benefit more than any of the others listed here from milder and shorter winters, presumably?

- A) Cranberry tipworm

- B) Blunt-nosed leafhopper

- C) Gypsy moth

- D) Cranberry fruitworm

- E) Cranberry weevil

- True or False: By the year 2050, if Boston were to experience 20 additional days above 90°F compared to now, climate change experts would not be terribly surprised.

- True or False: Warmer temperatures in September would aid in the darkening of the cranberry fruit (by increasing the level of anthocyanin in the berries).

- True or False: Warmer temperatures in the late part of the summer, when berries are present, could increase the risk of berry scald.

- True or False: Temperatures of 90°F and above during bloom can reduce the number of honeybees that are out pollinating.

- Which of the following insecticides appears to be the safest to bees?

- A) Admire®

- B) Altacor®

- C) Actara®

- D) Lorsban®

- E) Delegate®

- Which of these cranberry pests in the Northeast overwinters as an adult?

- A) Blunt-nosed leafhopper

- B) Redheaded flea beetle

- C) False armyworm

- D) Humped green fruitworm

- E) Cranberry blossomworm

- Which of the following is not true about the False armyworm?

- A) There is only a single generation per year.

- B) The eggs are laid in masses.

- C) The caterpillars do not cause much cranberry injury until very late in the season.

- D) The ‘traditional’ Action Threshold (AT) is 4.5 larvae per 25 sweeps.

- E) Once the caterpillars get to be large in size (~1” long or longer), they will begin to feed primarily if not exclusively at night.

- True or False: False armyworm caterpillars will not feed on the cranberry blossoms.

- True or False: The ‘Late Water’ flood, at least in Massachusetts, is effective enough to adequately control false armyworm.

- True or False: Cranberry weevil spends the winter as a pupa.

- Which one of the following statements is false?

- A) Eggs of cranberry weevil are deposited into the unopened cranberry flowers.

- B) A heavy infestation of cranberry weevil has the potential of destroying “much of the prospective crop” for that season.

- C) Female cranberry weevils—after depositing an egg inside the flower bud—will then generally chew on the stem of the flower bud, either severing it completely or at least weakening it such that the flower bud falls off later on.

- D) Cranberry weevils, when disturbed, are experts at ‘playing dead,’ making them difficult to find or see.

- E) Flower buds that are damaged by cranberry weevil will usually go on to produce a cranberry in spite of the damage.

- F) Flooding is believed to be ineffective at controlling cranberry weevil.

- True or False: Belay® may only be used post-bloom when targeting cranberry weevil because of its high bee toxicity.

- When are cranberry weevils most likely to be active and therefore more likely to be captured in one’s sweepnet when monitoring for them?

- A) Early in the morning, when it’s not so hot

- B) Right around sunset

- C) Most anytime that it’s windy

- D) From around noontime to 2:00 pm or so, on warm, sunny days

- E) When it’s dark outside (when they’re the safest from predators)

- Which one of the following statements is true?

- A) Cranberry fruit rot fungi thrive in dry and hot conditions.

- B) Fruit rot infection actually occurs or begins during the blossom stage, so warm and rainy weather during this time is likely to favor the fruit rot infection process.

- C) Getting less than 3.2” of total rainfall during the month of June awards 3 points to one’s total score with regards to the Keeping Quality Forecast Model.

- D) An increase of 12 to 13% in the intensity of a summer rainfall event would be good for cranberries, even if it occurred during bloom.

- True or False: Under a “business as usual” scenario, with more precipitation coming in the form of rain versus snow, winter for most of the northeast is expected to see a 25 to 50% reduction in the length of the snow season by the end of this century.

Answer Sheet for: “Cranberries and a Changing Climate” University of Maine Cooperative Extension. Instructions: You can email your quiz answers (if that is an option for you) to Charles Armstrong at charles.armstrong@maine.edu or, alternatively, you can print out this page with your quiz answers indicated, and mail to the Umaine Extension Diagnostic and Research Laboratory, c/o Charles Armstrong, 17 Godfrey Drive, Orono, ME 04473.

YOUR NAME: _______________________________________

A score of at least 80% correct will earn you one pesticide credit towards your pesticide license.

For ‘true/false’ questions, please write the entire word rather than just “T” or “F” so there is no confusion over which answer you mean.

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____

- _____