Maine Home Garden News — June 2019

- June Is the Month to . . .

- What Does Organic Gardening Really Mean?

- Moths: Another Important Backyard Pollinator

- Sundial Lupine and the Non-native Big-leaved Lupine

- Climate Impacts on Vegetable Farms: Interview with Lauchlin, Titus, CPAg

- Rose Chafer

- Maine Harvest for Hunger: 20 Years and Going Strong!

- UMaine Extension’s Home and Garden IPM Website Has a New Look!

- Food & Nutrition: Preserve Your Garden’s Harvest with a Hands-On Workshop This Summer

June Is the Month to . . .

By Kathy Hopkins, Extension Educator, UMaine Extension Somerset County

- Visit a pick-your-own strawberry operation to find the ripest berries of the season. You can find a farm on the Get Real Get Maine website.

- Closely observe your garden as frequently as possible. Look for leaf, stem, and blossom damage and note any suspicious insects. Make an accurate identification of the potential pest or pathogen before choosing any treatment. If you need help, bring the insect or diseased plant tissue into your local UMaine Extension county office for identification or e-mail digital pictures to your local office.

- Listen to the weather predictions for night time temperatures and be prepared to cover any cold-sensitive crops such as tomatoes, peppers, and cucumbers when temperatures go below 40°F. Tomatoes perform better with protection from temperatures cooler than 50°F.

- Direct sow: basil, beans, beets, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, carrots, cauliflower, corn, cucumber, dill, kale, kohlrabi, lettuce, peas, pumpkins, radish, shallots, spinach, Swiss chard, squash, and turnip. Consider repeat plantings for certain crops for a steady supply. Ornamental flowers, such as cosmos and zinnias, can also be direct seeded for an inexpensive pop of color in sunny gardens.

- Transplant seedlings of warm-season crops such as tomatoes, peppers, and eggplant.

- Use row covers to protect a wide variety of crops from flea beetles, cucumber beetles, cabbage moths, leaf miners, and other unwanted insects. Be sure to secure the row cover tightly along the edges, check under the row cover frequently for weed growth and sneaky intruders, and remove the row cover when insect-pollinated crops, such as cucumbers, are fully in flower.

- Keep an eye on rainfall amounts with a rain gauge. Most annual crops and newly installed perennials (woody and herbaceous) do best with 1 to 1.5 inches of rain per week.

- Annual flowers will benefit from split, small applications of fertilizer (proportioned every few weeks) during early summer. Don’t threaten lakes and streams by over-fertilizing. Removing spent flowers will maintain their flowering habit longer throughout the season. Most healthy established perennials (including trees and shrubs) do not require annual applications of fertilizers.

- Use mulch wisely in ornamental and edible plantings. Bark, wood chips, straw (not hay), shredded leaves, and pine needles all can work well in a variety of landscape settings, but should not be applied at a depth of more than 2” and not in direct contact with the stems of woody plants. Placing a few layers of wet newspaper down prior to adding organic mulches can help provide a good extra barrier for weed suppression.

- If invasive species are a problem in your garden or property, consider contacting the US Department of Agriculture Animal Plant Health Inspection Service in Maine via their website or at 207.848.0010. Frequent repeated cutting over a long period of time (often years) can be an effective management strategy for a number of our worst invaders, such as Japanese knotweed.

- Be aware of ticks. Extension’s new Diagnostic and Research Laboratory is now officially accepting tick samples for tick-borne disease testing. For information on submitting a specimen to the Tick Lab, as well as information on the different tick species of Maine, tick management, and personal protection, go to the Tick Lab or call 207.581.3880.

- If space is limited, consider growing vegetables and flowers in containers. You’ll find a great list of vegetable varieties suitable for small spaces in our Growing Vegetables in Container Gardens bulletin.

- Consider obtaining a copy of Pest Management for the Home Vegetable Garden in Maine, a 20-page publication with helpful photos from UMaine Extension.

- Compost grass clippings, leaves, and kitchen scraps. Find more information on how to have an efficient and productive system in our Home Composting bulletin.

- Make sure the birds have fresh water in bird baths or shallow dishes in the garden. Add some small rocks or float a few pieces of bark to create landing areas for insects to also access fresh water.

- Pinch back tall growing fall bloomers like asters, monarda, and helianthus to make them stockier and more floriferous.

- Celebrate National Pollinator Week, June 17-23, 2019

- Learn about the University of Maine Cooperative Extension Integrated Pest Management Program in Maine by visiting their website or calling 1.800.287.0279. The Integrated Pest Management website provides factsheets and a diagnostic service for plant-related diseases and insects as well as ticks.

- Tell a friend or colleague about Maine Home Garden News. Current and back issues are available.

Printed copies of UMaine Extension publications are available for purchase through our publications office. Call 1.800.287.1471 (toll free in Maine only).

What Does Organic Gardening Really Mean?

By Tori Lee Jackson, Extension Educator, Agriculture and Natural Resources in Androscoggin and Sagadahoc Counties

No pesticides? Using only certain pesticides? Buying products with the organic label?

Casual gardeners and the vast majority of consumers often have a vague or erroneous understanding of what the term “organic” really means when it comes to the foods and textiles they buy, or the practices associated with producing organic products. In simple terms, you might say that an organic gardener works with nature rather attempting to control it.

Since 2001, the term “organic” has had a legal definition according to the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) National Organic Program. The USDA Agricultural Marketing Service says in their Introduction to Organic Practices,

“The USDA organic regulations describe organic agriculture as the application of a set of cultural, biological, and mechanical practices that support the cycling of on-farm resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity. These include maintaining or enhancing soil and water quality; conserving wetlands, woodlands, and wildlife; and avoiding use of synthetic fertilizers, sewage sludge, irradiation, and genetic engineering. Organic producers use natural processes and materials when developing farming systems—these contribute to soil, crop and livestock nutrition, pest and weed management, attainment of production goals, and conservation of biological diversity.”

Organic growing means paying close attention to soil, water, and air quality, as well as wildlife and plant health, in and around your garden. It is as much about the inputs a gardener uses (compost, soil amendments, quality seeds, and seedlings) as what they do not use. Someone may opt not to use synthetic pesticides (including herbicides and fungicides) or fertilizers, but if they “recreationally rototill,” allow runoff from manure they apply to pollute surface water, exclude all wildlife, or clear cut their forest, there is nothing organic about their methods. As you can see, simply not using pesticides does not make a garden organic! In fact, there are thousands of pesticides and fertilizers allowed and used in organic agriculture. The Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI) is an international non-profit that maintains complete lists of products and genetic materials lists allowed in the United States and Canada. It is updated annually and available for anyone to find at their website.

Of course, organic gardening and agriculture have been around for much longer than the eighteen years since USDA defined it. The Maine Organic Farmers’ and Gardeners Association, known as MOFGA, has been educating and promoting organic practices since 1971, and is the oldest (and largest) state organic organization in the United States, certifying growers since 1974. An excerpt from their Why Organic? page describes their philosophy in this way:

Plants and animals raised organically are part of an agricultural ecology that includes a supportive, nourishing environment. Nourishing that environment depends on cycling organic materials as locally as possible by feeding soils with animal manures, green manures, composts and/or cover crops generated on or near the farm. It includes caring for soils so that they provide a welcoming home for the earthworms, beneficial microbes and other organisms that hold and cycle nutrients and that help bind soil particles together.

MOFGA offers many educational programs, hands-on workshops, online resources, the (very popular) Common Ground Fair, and much more to those interested in organic gardening, homesteading, and agriculture. If you’re not familiar, the Go Organic page on their website is a great place to start.

If you would like to begin managing your landscape and garden organically, the University of Missouri Extension’s Organic Vegetable Gardening Techniques is a comprehensive resource for learning about how to transition from conventional practices. You may have already noticed that the vast majority of resources and recommendations in UMaine Extension’s Garden and Yard website include low-input and environmentally-friendly tools and practices, appropriate for any type of gardening you wish to do.

For those interested in organic foods, getting to know your local farmers and talking with them about their production practices is a great way to learn more about what they are doing and why, so you understand what it takes to raise organic vegetables and livestock and can support your local economy at the same time.

Moths: Another Important Backyard Pollinator

By Ann Marie Bartoo, Master Gardener Volunteer

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, there are approximately 11,000 known species of moths in the US1. Along with butterflies, moths belong to the insect order Lepidoptera. Although they outnumber butterflies in their quantity of species, moths are often overlooked as a crucial part of our ecosystem. In many ways, we still see moths as a nuisance, but they deserve to be recognized along with other insects as part of nature’s grand scheme. Supporting moths in your yard and garden is easy to do—and without knowing it, you might already have a head start. Two types you may have seen in your yard include hawk moths and hummingbird moths.

Hawk moths are nocturnal and are drawn to flowers that tend to be white or light colored, have a tubular shape and produce high amounts of nectar (think nicotiana or evening primrose). Because these moths can travel between two and three miles in an evening, their ability to pollinate over a wide geographic area helps to improve and sustain diverse plant populations2. Members of the hawk moth family and countless other species of moths serve as an important food source for a variety of wildlife species including birds, other insects, bats, amphibians, and mammals. Unfortunately, the caterpillars of two species of hawk moths (tomato and tobacco hornworms) can cause quite a bit of devastation in home gardens in Maine. They have the ability to decimate plants in the nightshade family in a very short period of time. Visit our factsheet, Home and Garden IPM from Cooperative Extension for more information.

The hummingbird moth, on the other hand, is a daytime traveler. Similar to the hawk moth, it travels widely. While the plump, bird-like adults in this genus typically enjoy the nectar from red and pink flowers such as bee balm, phlox, verbenas, and thistles, their larvae prefer to feed on honeysuckle and trees and shrubs in the rose family. Be sure to leave some leaf litter available for these beautiful pollinators—the pupae spend the northeast winter under the cover of fallen leaves, then emerge as mature moths between April and August each year.3

Shrubs that support moths and/or are hosts for larvae include buttonbush, hydrangea, ninebark, viburnum, blueberry and cranberry.4 Host trees and perennials include clustered mountain-mint, red chokeberry, bluebell, flax leaf ankle-aster, floxglove, beardtounge, and rosy meadowsweet.5

Like other pollinators, moths play an important role in maintaining healthy ecosystems. The best way for you to support moths is by planting and encouraging native species in your yard and garden, as these species are familiar to them and have evolved along with them as part of their natural journey.

Additional information:

- Plants for Pollinator Gardens

- Landscaping for Butterflies in Maine

- Gardening to Conserve Maine’s Native Landscape

1 Hawk Moths or Sphinx Moths (Sphingidae)

2 The Year of the Sphingidae – Pollination

3 Hummingbird Clearwing (Hemaris thysbe)

4 Tree Planters’ Notes. (2016, Volume 59, Number 2). Dumroese, R Kasten and Luna, T. Growing and Marketing Woody Species to Support Pollinators: An emerging opportunity for forest, conservation, and native plant nurseries in the Northeastern United States.

5 Native Plants that Attract Pollinators (PDF)

Sundial Lupine and the Non-native Big-leaved Lupine

By Leala Machesney, Environmental Horticulture Student, University of Maine

Lupines are an important part of Maine’s cultural identify. Mainers and tourists alike flock to take pictures of fields filled with the deep purple flowers in mid-summer, but the plants that have become as associated with Maine as white pine or wild blueberry aren’t native to the state at all. Big-leaved lupine (Lupinus polyphyllus) is actually an introduced species native to the West Coast of the United States that negatively impacts Maine ecosystems where it becomes established. The exact date that big-leaved lupine was introduced to New England from the West Coast isn’t known, but most estimate sometime in the 1950s.

Sundial lupine (Lupinus perennis), not big-leaved lupine, is our native species. This native lupine has steadily lost its habitat due to expanding human land-use beginning in the early 1900s. A small population of sundial lupine does exist in New Hampshire, but the species is now believed to be extirpated from Maine.

Sundial lupine and big-leaved lupine are very similar in appearance. If you’re trying to determine whether you’re looking at sundial lupine or big-leaved lupine, a good place to start is to count the number of leaflets. Sundial lupine often has 5 to 7 leaflets, while big-leaved lupine has between 11 and 17 leaflets. The height of the raceme—the inflorescence bearing the purple flowers—is also a good way to differentiate between species. The raceme of sundial lupine will generally be between 10 to 20 centimeters. Big-leaved lupine has a much larger raceme, reaching between 20 and 40 centimeters.

The spread of big-leaved lupine negatively impacts Maine ecosystems in several ways. As many members of the pea family are do, both species of lupine fix nitrogen in the soil. While this can sometimes be a desirable trait, the large amount of land big-leaved lupine colonizes leads to the fixation of a high concentration of nitrogen. This makes the soil unsuitable for native plants that may be adapted to lower levels of nitrogen, can lead to the eutrophication of nearby bodies of water, and contributes to the emission of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide.

Perhaps the most well-known negative impact of big-leaved lupine in Maine is its effect on the karner blue butterfly. Sundial lupine foliage is the only food source for karner blue caterpillars, but it would be fatal for a karner blue larvae to feed on the foliage of a big-leaved lupine. That’s because big-leaved lupine has a high concentration of alkaloids toxic to the karner blue. Sundial lupine and big-leaved lupine hybridize easily, and the offspring they create have concentrations of this alkaloid too high for karner blue larvae to safely consume. There is a major effort underway in Necedah National Wildlife Refuge in Wisconsin to plant sundial lupine as a food source for their large population of karner blue butterfly. While a future where the karner blue and sundial lupine are reintroduced to Maine seems out of reach, there is still hope to preserve the critical habitat for these two species at Necedah.

References

Haines, A., Farnsworth, E., Morrison, G., & New England Wildflower Society. (2011). New england wildflower society’s flora novae angliae: A manual for the identification of native and naturalized vascular plants of new england. Framingham, Mass.;New Haven, Conn; New England Wild Flower Society.

Hiltbrunner, E., Aerts, R., Bühlmann, T., Huss-Danell, K., Magnusson, B., Myrold, D. D., Körner, C. (2014). Ecological consequences of the expansion of N₂-fixing plants in cold biomes. Oecologia, 176(1), 11-24.

Gibbs, J. P., Smart, L. B., Newhouse, A. E., & Leopold, D. J. (2012). A molecular and fitness evaluation of commercially available versus locally collected blue lupine lupinus perennis L. seeds for use in ecosystem restoration efforts. Restoration Ecology, 20(4), 456-461.

Maine Invasive Plant Fact Sheets from Maine.gov

Climate Impacts on Vegetable Farms: Interview with Lauchlin Titus, CPAg

By Sonja Birthisel & Erin Roche, Crop Insurance Education Program Manager, UMaine Cooperative Extension

To better understand the impacts of climate change on Maine vegetable farms, we asked Lauchlin Titus of Ag Matters LLC in Vassalboro, Maine, to reflect on his years of experience advising Maine growers.

Lauchlin has noticed a change in Maine’s weather, and describes this as “Patterns of extreme that last longer…hotter, colder, wetter, drier.” He also reports seeing changes in weeds, diseases, and insect pests over the years, noting as an example that cool, wet conditions in 2009 seem to have “resulted in Pythophtora capsici getting established on numerous vegetable farms that had never experienced it before.” Lauchlin goes on to describe strategies he thinks can help farmers adapt to changing precipitation patters, including use of “Raised beds with drip irrigation in vegetable production.” Read his interview in full.

This is part one in a series of Specialist Interviews the Maine Climate and Agriculture Network (MECAN) is collecting in order to share perspectives on climate change from different agricultural sectors in Maine. You can find out more about MECAN on our website, Maine Climate and Ag Network.

Rose Chafer

By Clay Kirby, Associate Scientist/Insect Diagnostician, UMaine Extension

The dreaded rose chafer is a scarab beetle from the same family as the Japanese beetle. Like the Japanese beetle, the rose chafer has a cream-colored “C”-shaped white grub larval stage and only one generation per year. In fact, rose chafer adults pretty consistently make their June appearance 2-3 weeks before the Japanese beetle adults, which show up in the Bangor area around the first week of July. However, this grub tends to be smaller than the Japanese beetle white grub, is not as serious a turf pest, and tends to be found more commonly in sandy soils. The adult rose chafer beetle is tan (this can vary a bit with some beetles having a greenish tint) with long reddish spiny legs and are about a 1/2-inch long. They are strong fliers, more likely to fly in warmer temperatures, and are somewhat protected by a toxic chemical in their bodies that is harmful to birds.

As the name suggests, rose chafers feed readily on roses, but their broad palate also includes other ornamentals, brambles, grapes, fruit trees, mountain ash, and some birches. Feeding damage first appears as shotholes in the leaves, but soon looks like lace-work as the skeletonizing feeding damage progresses.

Hand-picking can be an effective management strategy in smaller settings where infestations can be monitored on a regular basis. Simply knock the beetles into a coffee can about a third full of soapy water. Often the rose chafer will fall from the plant, playing dead, so make sure you have your coffee can below the beetle as you reach for it. Another least toxic approach is to cover vulnerable plants with a lightweight row cover material during the 3-4 week flight period of the adults.

A more aggressive management tactic would be to use an organic material such as pyrethrins or neem. These materials would likely have to be reapplied several times during the rose chafer feeding season and may have a negative impact on non-target species. Be sure to read label precautions and directions before purchase to see if this approach is something you want to consider and re-read the label just before use.

The most aggressive approach would be to use conventional materials. This would include synthetic pyrethroids or carbaryl (Sevin). Again, be sure to understand the potential impact on non-target species and read the label of products containing these active ingredients before purchase and also before use.

Fortunately, rose chafer beetles typically feed for only four weeks and healthy perennial plants are usually resilient enough to recover from significant defoliation. Therefore, regular hand-picking, the use of physical barriers, and having a reasonable level of tolerance for some feeding damage can often be the solution to getting home landscapes through an infestation without having to resort to more aggressive measures.

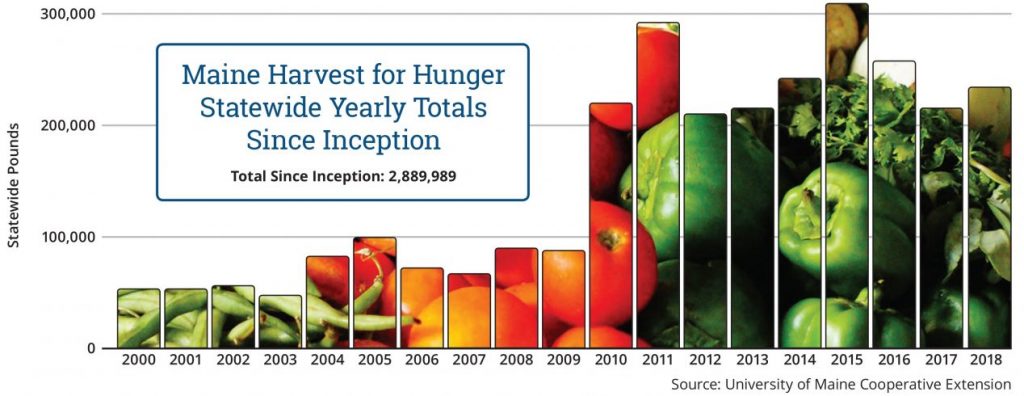

Maine Harvest for Hunger: 20 Years and Going Strong!

By Frank Wertheim, Extension Educator, UMaine Extension York County

Now that the 2019 gardening season has begun, it’s time to both reflect back and look ahead as the Maine Harvest for Hunger (MHH) program begins its 20th year. The MHH journey began in 2000, when a small group of UMaine Extension Staff and Master Gardener Volunteers met with Good Shepherd Food Bank staff to see they felt they could engage our Master Gardener Volunteers and the farming community to make a difference in face of a rising level of food insecurity in our home state of Maine.

Nearly 3 million pounds of top-quality food has since reached the tables of countless neighbors in need because of the extraordinary efforts of hundreds of volunteers and farmers from throughout Maine. Our collaboration has grown to include Master Gardener Volunteers, commercial farmers, home gardeners, 4-H youth groups, businesses, and civic organizations.

This has been a labor of love and learning, as many involved have gained invaluable experience in growing, gleaning, and distributing fresh produce to more than 200 food distribution sites (pantries, shelters, service providers, and public outreach partners). Volunteers are not only learning about food production, they’re also gaining a better understanding of food insecurity and the complex issues that are related to the hidden crisis happening in so many lives in our state.

Each year, the MHH team shares successes and challenges with each other and hunger partners across the state so we can continue to refine and improve our efforts. From these conversations, new elements that strengthen hunger efforts seem to be added every year. Examples include the Farmers’ Market Gleaning, Eat Well Volunteer, and Adopt-a-Family programs.

Gleaning, in particular, seems to be gaining more and more traction. Paths for developing and sustaining successful gleaning relationships between farmers and volunteers seem to be getting smoother all the time. Every gleaning partnership is unique in how we collaborate with farmers, volunteers, and food pantries. Communication and building community relationships are key to our long-term success. Where one farm may have our local gleaning team “on call” should they have excess produce, other farms plan in advance for us and some are even planting parts of their crops with the intention for us to glean.

Getting over 200,000 lbs. of fresh produce annually distributed to close to 200 distribution sites takes a lot of communications and logistical considerations. Many food pantries are restricted in what kind of produce they can handle, what their hours are, and what their storage capacity is. Everyone needs to be on the same page to make sure the fresh produce is moved quickly from the farm to the distribution site and out into the community where it is needed. Pantry volunteers frequently comment how much the high-quality fresh produce means to recipients, many of whom otherwise would have limited access to them. One person commented that they had not eaten a fresh apple in over a year and was overwhelmed with joy when a food pantry volunteer provided them with a bagful.

As we look ahead to the future, we are now more focused on educational programs that engage food pantry recipients, seniors, and community gardeners in growing more of their own produce and learning practical methods of cooking and utilization of fresh produce. There are many different ways to get involved. Connect with your local coordinator to learn more about how you can join our team.

UMaine Extension’s Home and Garden IPM Website Has a New Look!

UMaine Extension’s Home and Garden IPM Website Has a New Look!

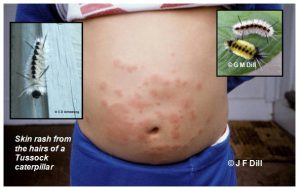

Be sure to check out our newly updated Home and Garden IPM (Integrated Pest Management) website. You’ll find photo galleries, identification tools, and fact sheets on a wide variety of insects, spiders, ticks, and weeds. Bookmark it for future reference!

Food & Nutrition: Preserve Your Garden’s Harvest with a Hands-On Workshop This Summer

By Kate McCarty, Food Systems Professional, UMaine Extension Cumberland County

We’ve all been there—whether it’s due to enticing seed catalogs in February or the groaning tables of hopeful seedlings at the local farmers’ market, excitement about the coming growing season can lead us to overplant. Come July and August, the garden is starting to churn out some serious amounts of produce. A new cucumber seems to be hiding under every leaf, the Swiss chard is knee-high, and who knew one tomato plant could make so many ripe tomatoes at once? If this scenario sounds familiar, perhaps you’re in need of some basic food preservation skills that will help you “put up” your garden’s harvest.

From canning jams, pickles, and tomatoes to freezing greens, drying herbs, and fermenting vegetables, UMaine Extension hands-on food preservation workshops will teach you how to maximize your garden’s harvest. Gone are the days of marathon preserving sessions with bushels of peaches and tomatoes (well, some of us still choose to do that, but it’s not the only way). Instead, think of blanching a batch of kale for the freezer, infusing vinegar with fresh herbs and fruit, or canning a batch of salsa using your homegrown tomatoes and peppers. Our hands-on food preservation workshops will give you the basic skills and quick tips to make preserving your harvest fit readily into your already full life.

Every UMaine Extension food preservation workshop will teach participants the basics of canning and freezing. Specialty workshops on fermenting, drying, and pressure canning are also offered. Workshop participants will receive a “Preserving the Harvest” food preservation packet, and will learn recommended methods for preserving foods, the latest and safest recipes, about equipment to insure safety and how to check for properly sealed jars. Instructors provide the fresh produce, canning jars, and recipes—you can just show up and enjoy a fun afternoon or evening of cooking and learning. One of the best parts of these workshops is the opportunity to exchange gardening, cooking, and preserving tips with other gardeners and local food lovers. At the end of class, every participant goes home with a jar or sample of what we made.

UMaine Extension staff and volunteers offer food preservation workshops in nearly all of Maine’s 16 counties. Our robust summer schedule is kept up-to-date on our site Food Preservation Hands-On Workshops. If there’s not a workshop scheduled near you, use the form to request a workshop, and we’ll come to your community. We hope to see you at one of our workshops this summer!

For other food preservation resources, visit UMaine Extension Food & Health website and our Publications catalog.

University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s Maine Home Garden News is designed to equip home gardeners with practical, timely information.

Let us know if you would like to be notified when new issues are posted. To receive e-mail notifications fill out our online form.

For more information or questions, contact Kate Garland at katherine.garland@maine.edu or 1.800.287.1485 (in Maine).

Visit our Archives to see past issues.

Maine Home Garden News was created in response to a continued increase in requests for information on gardening and includes timely and seasonal tips, as well as research-based articles on all aspects of gardening. Articles are written by UMaine Extension specialists, educators, and horticulture professionals, as well as Master Gardener Volunteers from around Maine, with Katherine Garland, UMaine Extension Horticulturalist in Penobscot County, serving as editor.

Information in this publication is provided purely for educational purposes. No responsibility is assumed for any problems associated with the use of products or services mentioned. No endorsement of products or companies is intended, nor is criticism of unnamed products or companies implied.

© 2019

Call 800.287.0274 (in Maine), or 207.581.3188, for information on publications and program offerings from University of Maine Cooperative Extension, or visit extension.umaine.edu.