Blunt-nosed Leafhopper

Order: Homoptera || Family: Cicadellidae

Scientific Name: Limotettix (=Scleroracus) vaccinii (Van Duzee)

- Blunt-nosed leafhopper nymph in Maine on a standard piece of lined notebook paper – 5/19/2010 (it is about the size of a flea)

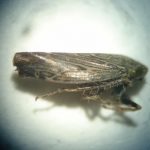

- Magnified view of a Blunt-nosed leafhopper nymph in Maine – 5/19/2010

- An adult Blunt-nosed leafhopper resting on a cranberry insect sweep net (in Maine)

- Blunt-nosed leafhopper (on the rim of a 12″-diameter insect sweep net)

- Blunt-nosed leafhopper adult

- Blunt-nosed leafhopper adult

- (Closer View) Blunt-nosed leafhopper adult in Maine (6/25/2015)

- Even Closer View: Blunt-nosed leafhopper adult in Maine (6/25/2015)

- Greatly Magnified View: Blunt-nosed leafhopper adult in Maine (6/25/2015)

- Another magnified view of a Blunt-nosed Leafhopper Adult in Maine

- Blunt-nosed leafhoppers inside a cranberry insect net (in Maine; Year 2009) (The view here is looking down into a 12″-diameter sweep net after only 25 sweeps)

- Closer view of many Blunt-nosed leafhoppers inside a cranberry insect sweep net following 25 sweeps across a Maine cranberry bed in 2009

- Blunt-nosed leafhoppers inside a cranberry insect net (in Maine; July 3rd, 2015) (after 25 sweeps with the net)

- Closer view of the photo at left, with each Blunt-nosed leafhopper circled.

Photos by Charles Armstrong.

Not seen in Maine’s modern cranberry era until the 2009 growing season, when it was found at two separate locations, with a large outbreak at one of those locations. Another location saw high numbers of them in 2015 and 2016, and they were found fairly routinely on many Maine cranberry beds in 2017 and 2018.

Notes: This is a ‘piercing-sucking’ insect in the manner in which it feeds, and most of the feeding is done throughout the nymphal stages, when they are wingless (only the adults have wings). The nymphs (see photos below) need to molt a total of five times before becoming adults, and this development period lasts about one month. The adults may be found from June all the way through early September (with the first hard frost eliminating any stragglers), and their numbers will swell and peak in July or early August. In very high numbers (100 to 200 per 25 sweeps), leafhoppers can drain the vines significantly (robbing the stems of water and sugar), but most importantly, it is a known carrier of the plant phytoplasm (virus-like pathogen) known as False Blossom, which threatened the entire cranberry industry nationwide in the early 1900s and was so bad in New Jersey that it is said to have nearly ended their cranberry industry there altogether. The disease manifests itself as deformed blossoms that do not set fruit. It is being found again in New Jersey, and pockets of it are still found in wild bogs on Cape Cod in Massachusetts, and more recently it has been detected at a couple of commercial Massachusetts bogs in 2017 and 2018.

You can learn more about this pest on pages 61 to 63 of A.L. Averill & M.M. Sylvia’s book, Cranberry Insects of the Northeast. There are two photos of False Blossom disease at the bottom of page 62.