Cranberry Tipworm

- Cranberry tipworm eggs

- Three Cranberry tipworm Eggs

- Two Cranberry tipworm eggs

- 1st-instar cranberry tipworm larva perched atop the tip of a pair of forceps

- Cranberry tipworm 2nd instar larva (‘white’ stage)

- Cranberry tipworm 2nd-instar larvae (white stage)

- Magnified view of a cranberry tipworm 3rd-instar larva

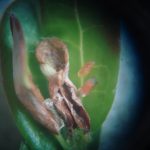

- Cranberry tipworm 3rd-instar larva

- Cranberry tipworm 3rd-instar larva

- Cranberry tipworm 3rd-instar larva as viewed closer to what the naked eye would see

- A pair of Cranberry tipworm Cocoons

- A Cranberry tipworm pupa removed from its cocoon

- The pupal case left behind after a cranberry tipworm fly emerged from it.

- An empty cranberry tipworm cocoon (after the fly has emerged)

- Magnified view of a cranberry tipworm fly/midge – Dasineura oxycoccana (females are orange; males are black)

- Cranberry tipworm fly/midge beside a U.S. dime (for scale purposes)

- Cranberry tipworm fly/midge beside a U.S. dime (for scale purposes)

- Injury from Cranberry tipworm larval feeding (terminal growing point is clearly dead)

- Rebranching (regrowth) of lateral buds that takes place following tipworm injury to the terminal bud

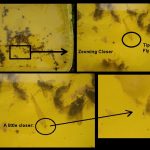

- A yellow cakepan with soapy water that is being used by some growers for monitoring for presence of cranberry tipworm flies

- Brand new cranberry tips at the start of the season; these tender, new tips are the ones upon which female tipworm flies will lay their eggs at the very start of Maine’s cranberry growing season.

photos by C. Armstrong (some additional photos below)

Pest Status: This insect has caused a tremendous amount of debate among scientists and growers alike as to its true destructive potential in cranberry. Although disputed by many growers, researchers in Massachusetts have conducted numerous studies over the years which have led them to believe that vigorous, healthy vines very often recover from tipworm injury–even when tipworm populations are very high–and go on to yield well (both in the same year as the injury, as well as in the subsequent year). The collective wisdom today is that this may very well be the case for Massachusetts, but may not be the case for cranberries that are grown in more northern parts of North America that experience shorter growing seasons–for example, Wisconsin, Michigan, Maine, and Washington in the US, and also in Canada (British Columbia, and the Atlantic Provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and PEI). In Wisconsin, differences in yield impacts on cranberry due to tipworm injury have been seen according to whether the cranberries were located in northern Wisconsin, or southern Wisconsin, suggesting that geography does in fact play a major role in determining the full impact that cranberry tipworm can have on a grower’s bottom line. The consensus in Maine, especially amongst growers, is that cranberry tipworm has a very significant negative impact on yield, and a recent, though as yet unpublished, study in Maine looking at tip damage and tip recovery following tipworm injury adds support to tipworm’s status as a serious cranberry pest for Maine [virtually none of the tips examined and tagged in the study–that were injured by tipworm–went on to flower the following year, whereas virtually 100% of undamaged tips did go on to flower the following year].

Life Cycle: Tipworm goes through several generations–anywhere from 3 to 5–per season (the scientific term for this is multivoltine), and by early June, one will find an overlap in the generations occurring, where each of the life stages may be found at any one time (eggs, larvae, pupae, and flies). Larvae progress through three instars, each of which is marked by fairly obvious size and/or color differences. First instar larvae are best described as being ‘clear,’ having literally a see-through quality to their appearance. Most 2nd-instar larvae are larger/plumper, and are noticeably white in color. Finally, 3rd-instar larvae are distinctly orange in color. Pupation takes place right in the tips themselves, and the pupal stage reportedly lasts for 5 days. The total generation time can take as few as 14 days (egg to adult may take only about 10 days by comparison), but under sustained cooler or rainy conditions, it might take up to 28 days for a generation to complete. The insect overwinters, reportedly, as a pupa on the floor of the cranberry bed. In Maine and Massachusetts, the adult flies (just 2 mm in length)begin to emerge in early May or at first bud break. Maine growers can also keep watch for the first signs of the weed, horsetail (equisetum), as a further signal for the likely presence of tipworm fly activity (look for horsetail plants that are anywhere from 3 – 6″ high). The flies mate and the females presumably lay their eggs shortly thereafter, as the flies are believed to live for only about 3 days (but perhaps longer than that under cooler conditions, or in the safety and comfort of the lab where they’ve been found to live from 4 to 5 days). A 1996 study in Wisconsin found that the eggs hatch within only a few hours following oviposition. In Maine, observations would suggest that, at least during May, it seems to take at least a day or more for eggs to hatch.

Feeding Injury: The larvae of cranberry tipworm, as the name implies, feed on the tips of cranberry uprights and runners (new growth only). They are equipped with scraping mouthparts that, upon feeding, results in a characteristic cupping and whitening of the terminal leaves. Sustained injury from feeding leads to the death of the growing point, and the blackened result may sometimes be confused with frost damage or even heat stress. The plant responds to the loss of the terminal growing point by rebranching from lateral buds in an attempt to compensate for the damage. For most uprights damaged late in the season (for Maine, late July & early August), it appears that the regrowth produces primarily vegetative rather than fruiting buds, giving rise to a potentially significant reduction in the following year’s crop, depending on the overall level of tipworm infestation and injury in the bed, and how late in the season the injury takes place. By contrast, early-season tipworm injury is believed to be far less worrisome than late-season injury, due to the question as to whether or not the plants have adequate ‘growing-season’ time remaining in order to set fruiting buds for the following season.

Monitoring: Due to its very small size, cranberry tipworm, in all of its life stages, can be challenging to monitor. Results with sticky traps have varied too much to be trusted, or have not correlated well with the actual populations in the field. The flies do get picked up in fine-mesh or muslin sweep nets, and since the females are bright orange in color (unlike any other fly of that same size occurring in that habitat or at that time), one can at least have some sense of the extent of the tipworm infestation taking place simply by sweeping at least once per week. But for the most accurate picture of a tipworm infestation at any given time, one needs to go through the laborious process of using a dissecting scope or some other powerful magnification means in order to examine actual uprights for the presence of eggs, larvae, and pupae. A sample should consist of 40 to 50 randomly-collected uprights from each bed you wish to assess. Be careful not to collect all of them from just one or two spots in a bed, as their infestation levels have been found to vary somewhat within a given bed from one area to another, or between edges and the rest of the bed, for example. Walking in an‘X’ or diagonal pattern, collecting a few uprights here and there as you go, and placing them in a plastic zip-lock type of bag, is a good method to use. Zero in on each upright you wish to collect, visually, before taking measure of whether or not you can see any early ‘cupping’ injury, i.e. do not allow your sampling to be biased towards tips that you feel may, or may not, have tipworm already present. The sample needs to be ‘truly’ random. Samples should be taken at least once per week, prior to bloom [after the bloom period, sampling frequency can be reduced], and inspected using a low-power, dissecting-type microscope, and the numbers of the various life stages (egg, clear larva, white larva, orange larva, cocoon) recorded. Egg laying begins within one week of the first shoot elongation; sampling should begin at this time. Populations usually decline by the end of flowering and monitoring can be reduced at this point. Determine the percentage of uprights that are infested with tipworm, and keep a record of how many of each of the different stages of tipworm were observed for each tip in the sample. A spreadsheet with a table is useful for this purpose, with a single column reserved for each tipworm life stage (eggs, 1st-instars, 2nd-instars, 3rd-instars, and pupae), and each row of the spreadsheet thus signifies a single cranberry tip.

Control: For specific and current control recommendations for Maine, please refer to the Maine Cranberry Pest Management Guide.

Quick Facts and Management Tips:

- Cranberry tipworm is a very small insect (eggs are only 0.35 mm in length, larvae are only 1.5 to 2 mm in length, and the adult flies are only 2 mm in length, which is only about one-tenth the size of a typical mosquito!)

- Females lay their eggs near the base of the terminal leaves, only on new or current-season shoots (hard to see them without a dissecting scope, and if you are searching for eggs at the start of the season, don’t sample last year’s growth).

- Egg oviposition starts in early May or as soon as there are new tips present (sample and examine the tiny, new shoots rising up from the runners)

- Larvae feed (rasp) on the youngest leaves at the tips of uprights, right at the growing point.

- Injured leaves lose their color, become cupped, and eventually die, along with the growing point.

- As many as 5 generations of larvae may occur per season, though the highest populations are seen during the first three generations, when the cranberry foliage is growing most actively and therefore is more succulent and nutritious to the developing maggots (populations begin to decline after bloom).

- Early-season injury leads to lateral branching (new side shoots), but these side shoots are then targeted and attacked by the ensuing tipworm generation.

- Late-season injury appears to result in mostly non-flowering uprights the following year (at least for cooler, northern climates). [“Late-season” in Maine is late July and early August]

- Last-generation of larvae overwinter on the bed (within the trash layer) reportedly as pupae.

- Avoid conditions leading to excessive vine growth because tipworm larvae need actively-growing tissue (Take stock of your tipworm situation before putting out any late-season nitrogen applications)

- Sanding–especially heavy sanding (1.5 – 2″)–reduces populations, particularly early spring levels; However, after just a few weeks, levels generally increase again so the tipworm population suppression is only temporary, but this might nevertheless afford some advantages to the grower depending on the specific situation and management goals.

- B.t. (kurstaki strain) will not control tipworm since it is a fly and not a caterpillar; the kurstaki strain used in most pest control programs is not toxic to the digestive system of flies (larvae or adults).

- Due to the uncertainty about the true economic damage levels resulting from tipworm, no researched economic threshold or action threshold (AT) exists for cranberry tipworm.

Some Natural Enemies of Cranberry Tipworm:

- A parasitic wasp called a Sword-stabbing wasp which happens to aggressively parasitize cranberry tipworm larvae!

- Two Sword-stabbing parasitic wasps

- Closer view of a Sword-stabbing parasitic wasp

- A species of Syrphid fly (also called a Hover fly or Flower Fly) — Toxomerus marginatus (a natural enemy of cranberry tipworm larvae)

- Syrphid Fly (same species as adjacent photo)

photos by C. Armstrong

Examples of some dead 3rd-instar cranberry tipworm larvae (presumably killed by a novel insecticide containing the active ingredient, novaluron):

photos by C. Armstrong